Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Economia Global e Gestão

versão impressa ISSN 0873-7444

Economia Global e Gestão v.14 n.3 Lisboa dez. 2009

SMEs and internationalization: an empirical study of SMEs in Portugal

Virgínia Trigo*, Teresa Calapez** e Maria da Conceição Santos***

ABSTRACT: This paper presents the results of a survey of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Portugal drawn from a database of 2500 SMEs supplied by COFACE – the holder of the largest company database in Portugal. It is an exploratory study presenting descriptive results on their export drive, competitiveness in external markets, analysis of the environment, and innovation concerns vis-à-vis global markets and information needs for these markets. We draw from recent literature to identify the main features global markets require of companies if they are to operate successfully and compare them with our findings. Portugal was selected as the basis of our study not only because local companies have faced great changes in the last three decades following the transition from a closed and protected economy to full membership within the European Union and the current very open economy, but also because the country and population are so small that companies face tremendous pressures to internationalize as the domestic market for many types of goods is very limited.

Keywords: SMEs, SMEs in Portugal, Internationalization, Globalization

TÍTULO: Internacionalização e PME: um estudo empírico sobre PME em Portugal

RESUMO: Este estudo apresenta os resultados de um inquérito realizado em Portugal junto de 2500 pequenas e médias empresas (PME) constantes da base de dados da COFACE. É um estudo exploratório e apresenta resultados descritivos sobre a orientação para a exportação, competitividade nos mercados externos, capacidade de análise da envolvente e inovação relativamente ao mercado global bem como as necessidades de informação das PME inquiridas relativamente a esse mercado. A partir de literatura recente identificámos as características principais que o mercado global exige das empresas para que nele possam operar com sucesso e comparámo-las com os resultados que obtivemos. Seleccionámos Portugal como base do nosso estudo não apenas porque as empresas locais têm vindo a sofrer profundas alterações nas últimas três décadas tendo passado de um ambiente protegido para o contexto aberto da União Europeia, mas também porque, sendo um país pequeno, com um reduzido mercado interno, sofrem enormes pressões no sentido da internacionalização.

Palavras-chave: PME, PME em Portugal, Internacionalização, Globalização

RATIONALE FOR THE STUDY

A widely used term, globalization – of which internationalization is one aspect – encompasses many facets of an increasingly integrated world. The resulting interdependence has particularly affected international trade with large companies at the forefront of the move. While large companies have the market ambition, positioning, financial and organizational muscle to be the drivers, small and medium-sized companies (SMEs), the bulk of any economy, cannot be immune to it. Given that SMEs should internationalize as it has been fully demonstrated that benefits derived offset the costs (Pangarkar, 2008) , we wanted to examine the situation of SMEs in Portugal and investigate how their position towards this imperative.

There is no lack of literature on the topic of internationalization of SMEs especially in recent years (Karagozoglu & Lindell, 1998; Pangarkar, 2008; Prater & Ghosh, 2005) , but studies on the Portuguese situation are scarcer. However, we believe it warrants research in part because a little over thirty years ago Portuguese companies emerged from a closed and protected economy into full membership to the European Union and into the current very open economy; on the other hand, like other small countries with small populations, companies in Portugal face tremendous pressures to internationalize due to the limited domestic market for most types of goods and services. In addition, the sheer weight of SMEs in the Portuguese economy makes them worthy of study: they now represent 99.6% of all Portuguese companies, are responsible for 75.2% of jobs and for 56.4% of business turnover. This growth trend has been heightened in recent years: from 2000 to 2005 the number of SMEs increased at a yearly rate of 7% (against a 1.1% growth for large companies), secured a job growth of 4.2% per year and a yearly turnover increase of 4.2% (IAPMEI, 2008) [1].

How do Portuguese SMEs face internationalization? A study conducted in 1987 (Santos António & Trigo, 1991) among owners/managers of small companies showed that there were serious concerns a year after EU integration over the competitiveness and aggressiveness of Spanish firms; respondents expressed their fears that sectors not traditionally involved in exports (textile, shoe industry ) would suffer the most (pp.17-18). What is the situation now? How do companies think in terms of designing their strategies, nationally or internationally? What do they lack most in order to go beyond borders? This paper aims at answering these questions.

We will start our paper by reviewing the literature on the general arguments about internationalization of SMEs. A snapshot of SMEs in Portugal will follow as well as the presentation of the research design, and of the findings of the survey. We conclude by recognizing the limitations of our study and by indicating directions for further research.

DEFINING SMEs, GLOBALIZATION AND INTERNATIONALIZATION

There is no uniform definition across countries of an SME and, as the factors that set them apart are essentially qualitative and comparative, a universal definition is perhaps unnecessary. In this paper we have adopted the recommendation by the European Commission no. 2003/361/CE in force since January 2005 that defines small and medium-sized enterprises as those with less than 250 employees and an annual turnover of less than 50 million euro. This recommendation was later included in Decree-Law 372/2007 of November 6 (annex, no. 1, article 2) by the Portuguese Government.

According to Lee & Maniam (2007) , globalization is a process developed over time, through mans innovation and technological advances. It includes integrating world economies, predominantly through financial and trade advancement. According to these authors, there are four main aspects of globalization to consider: (1) trade, (2) capital movements, (3) the spread of knowledge and technology leveraged by the fast rise in Internet consumption by both enterprises and the average population and (4) international business employment.

One of the effects of globalization has been the sharp increase of international trade and though we often use the term internationalization in this paper as a substitute for globalization, we must recognize that it is only one aspect of the latter. As communications and transportation innovations have made international trade more economically feasible, companies have been pushed to go across national frontiers: first they internationalize and eventually globalize. While twenty years ago the rapid movement towards the consolidation of a new stage of globalization was unpredictable, it has been taken place due to the development of factors such as international politics, science and technology, and, above all, to the increase of the practice of safely buying and selling over the internet. As sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (1998, p. 2) puts it, globalization divides as much as it unites but it is an irreversible process that affects us all.

Guburro & OBoyle (2003) refer to economic globalization as all the entities operating in a variety of countries, offering goods on the world market, changing their location on the basis of growth and profit opportunities and supporting their growth by their own efforts without the support of a nation. SME globalization is understood as the extent to which SMEs realize opportunities in foreign markets either by exporting, licensing or selling technology or by engaging in foreign direct investment. Any private company can potentially become global.

GLOBALIZATION REQUIREMENTS

Due to the fixed costs involved in internationalization efforts and the higher percentage of these costs in an SME than in a large firm, the ability to gather and use considerable resources has been considered a requirement to compete abroad (Mundim, Alessandro & Stocchetti, 2000) . Firm size is then often mentioned as playing an important role for a company to go international: in order to compete globally you need to be big (Chandler, 1990) ; and therefore a disadvantage for SMEs. If a certain internationalization initiative fails, the impact on an SME will be greater, therefore increasing its risk level (Lu & Beamish, 2001) . A further stress on resources comes from the need to increase communication among a firms different units and with other parties located in different areas of the world which is perhaps made easier in the case of a larger firm.

However, in the past decade, the academic debate on internationalization has been focusing more deeply on the specific features of small firms in their attempt to establish a strategic goal to be a global firm in a global world market (De Chiara & Minguzzi, 2002; Mughan & Lloyd-Reason, 2007) . This trend considers that although the relationship between firm size and the ability to be an exporter has attracted considerable research attention, globalization is not exclusively a multi-national or big firm issue as the literature on born global companies demonstrates. Many small or medium-sized enterprises thrive through globalization and achieve significant growth of sales and economies of scale (Mughan & Lloyd-Reason, 2007; Winch & Bianchi, 2006) but although it has been empirically demonstrated that international sales of SMEs can also reach high levels (Calof, 1993) SMEs share in the total value of international trade continues to be lower than their share in GDP either because of the difficulties encountered in the domestic market that drive them to enter foreign markets/countries or because of their own advantages and abilities; this is evidence of the barriers that many of them face when seeking access to international markets (Mughan & Lloyd-Reason, 2007; Westhead, Wright, & Ucbasaran, 2001) .

Global markets also require firms to perform systematic environmental scanning to get the information they need in order to capitalize on the opportunities offered (Buckley, 1999) . As Qian (2002) noted, there is a scarcity of information because most SMEs do not possess specialists to monitor and manage international operations, and in general suffer from a shortage of managerial resources. These problems, coupled with time management difficulties, often push SMEs to take short-cuts in decision-making and information collection that can have devastating consequences and lead them to sink abroad and at home.

In addition to firm size, previous research efforts have found a number of firm characteristics linked to SME export performance. They include: international experience, dependence on exports, and adaptation of product for sale in foreign markets. Innovation is yet another requirement for international competition (Gadenne, 1998) . As research is a prerequisite for innovation, how can SMEs access and utilize finance to develop new products and processes? The 2nd OECD Conference of Ministers Responsible for SMEs issued a communication (OECD, 2004) prompting the establishment of innovation networks and the termination of barriers impeding networking by SMEs as a way of overcoming this problem.

Research conducted on Born Global companies – and on Born-again global as an extension to the previous phenomenon – also gives important hints on how SMEs may overcome their limitations. After all, they are SMEs and global at birth. For example Oviatt & McDougall (1994; 1999) mention the widespread use of creative strategies such as alliances as a way of obtaining the capabilities required to operate globally. While it has taken multinational big firms years and considerable sums to build market channels in order to expand and penetrate foreign markets, new born companies going global – and emergent economies alike – have questioned some of the usually mentioned limitations. Born global firms may lack resources to establish subsidiaries but they use hybrid organizational distribution channels such as close relationships and network partners to conquer the global market rapidly (Gabrielsson & Kirpalanni, 2004) .

According to Brouthers & Nakos (2005) , scholarly research on the factors that determine the success of an SME to export has tended to focus primarily on two factors: on one hand, studies on firm-specific characteristics that influence a firms international behavior as previously mentioned and, on the other hand, the influence of decision-maker characteristics on the export behavior of the firm and its performance. In this regard, two decision-maker traits have been linked to SME international success: age and educational level of the decision-maker.

Many authors have emphasized the benefits of internationalization to firms which has proved useful to make companies more competitive in their local markets too (Claessens & Schmukler, 2007) . Although firm size poses obstacles to the internationalization of SMEs, they do have means to overcome this hindrance either by forming alliances that would allow the leverage of resources such as environmental scanning or by innovating, a process enabled by the advance of telecommunications that facilitates networking and communities of practice. Such advances also ease the burden of communication costs that have posed restrictions on the internationalization of SMEs. However, current literature still recognizes that many SMEs often lack the resources needed to be successful abroad, such as researching foreign markets, adapting products and developing foreign channels (Knight, 2000; Mughan & Lloyd-Reason, 2007) and face a more structural handicap in the form of limited financial and human resources (Baird, Lyles, & Orris, 1994; Pangarkar, 2008) . In sum, many SMEs still cannot enjoy all the options in the internationalization process outlined in the literature (Baird et al., 1994; De Chiara & Minguzzi, 2002; Mughan & Lloyd-Reason, 2007) and given their weight in any countrys economy it would be in everyones interest to help them to achieve so. That is another aim of this study in the framework of SMEs in Portugal.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

To gather information on how Portuguese SMEs are responding to the need to internationalize and how prepared they are, we designed a survey instrument that was mailed and collected over a 3-month period (December 2007 to February 2008). We used a database of the 2500 largest Portuguese SMEs supplied by COFACE – the holder of the largest company database in Portugal – as the sampling frame for mailing the questionnaires. The database did not include micro-enterprises (those with less than 10 workers and a turnover of less than 2 million euro).

Close to 13% of the questionnaires were returned due to incorrect address, business liquidation or incorrect focus. This illustrates what may be a key hurdle in SME research: they frequently change status, fail in the first years of existence and are much less stable than larger firms. Besides, our survey is a six-page questionnaire that may have required a little too long to complete and we asked respondents a variety of questions that some may have considered sensitive. The questionnaire was to be answered by the decision-maker, preferably from top level management. We enquired about the companys basic data, the main problems it faces, prospects of development, support deemed necessary for development, and information about the company and innovation. This is an exploratory, descriptive study that aims at providing a first picture of the surveyed Portuguese SMEs and for this first paper we selected issues regarding internationalization, innovation and strategy development.

We received 248 usable questionnaires, giving us a response rate of 11.4%. Although the response rate appears to be low, it is within international standards for this kind of survey, and still gives us an acceptable number for statistical processing. Ninety five companies in our sample are small (with 11 to 50 employees and a turnover between 2 and 10 million euro) and the rest are medium-sized. Around two thirds have a family foundation background; most have 20 to 49 employees (35.1%) or 50 to 99 (31.5%); the average percentage of employees with any academic level is very low, around 9% globally. The figure increases to 16% for those companies in the service sector. Respondents were top management (39.1%), middle management (35%) and technical staff (25.9%). Most possess graduate degree or post graduations(79.4%); a few have high school or vocational studies (13.9%) and the rest have primary school, 9 of whom occupy top-management positions. The majority of the respondents are male (67.3%).

Although almost half of the companies (49.4%) do not have any export activity, we observed that this is highly dependent on the sector in which companies are operating. While those in the service and civil construction industries report little or no export activity, around 42% of the manufacturing firms surveyed stated they exported more than half of their production with less than 20% declaring that they produce for the domestic market only.

FINDINGS ON INTERNATIONALIZATION

Firms were first asked about the main difficulties they face and that may hinder their intentions to expand. Close to half of the respondents (46.3%) claimed they had difficulties in hiring qualified staff. This percentage is more relevant in the manufacturing sector, with 62.6% of positive answers. Besides this problem, almost all respondents (88%) feel the need to qualify their own workers by improving their skills.

Only 90 out of 246 consider that the firm is working below their own production limits (36.6%). Half of these have no exporting activities and mainly refer to (national) recession (29 out of 45, 64.4%) and/or to (internal) competition (26 cases, 57.8%) as the root of this problem, although one third also mentions cash flow problems. Recession (24 out of 45) and competition (26/45) are also the main reasons for the remaining 45 respondents. However, for those who export more than 50% of the production (16/45), competition (12/16) proves to be a more important motive than recession (5/16) for the under usage of their production capacity. Product life cycle, price structure, exchange rates are other recurrent quotes.

In the above mentioned 1987 study, only 45.5% of the then respondents considered that most SMEs were meeting contracted delivery dates but this percentage has increased to a significant 70% in the present survey which may suggest a different, more positive attitude from currently surveyed SMEs.

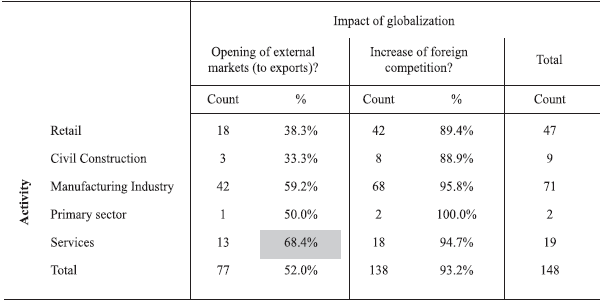

Enquired on the impacts of globalization, 70%, i.e. 171 surveyed companies, admit to have experienced them through an increase of foreign competition (147/171), but also through the opening of external markets to export (82/171, 48%). Table 1 below illustrates how these answers divide among the different sectors.

TABLE 1 – Impact of globalization (by sector)

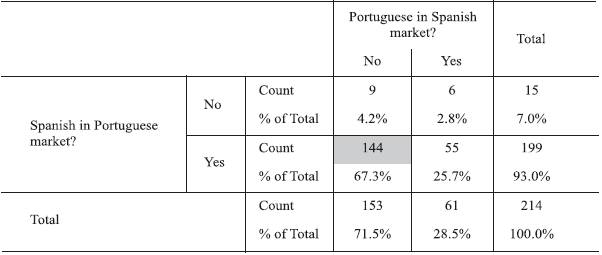

Due to geographical proximity and interdependence of markets, we enquired specifically on the relationships with Spain. Similarly to the 1987 survey, most companies (199) mention that the simultaneous integration (in 1986) of both countries in the European Union has made Spanish companies more aggressive in the Portuguese market although the opposite may not be true: only 61 respondents report having observed greater aggressiveness in the Spanish market by Portuguese companies as shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2 – Aggressiveness of Portuguese and Spanish Companies

FINDINGS ON INNOVATION

Respondents were asked about the level of innovation of their product, productive process, organizational system and marketing. Fourteen chose not to answer any of these four questions while 15 did not answer the first two items. They are mainly from the retail sector where the idea of product and productive process may be harder to define. Around 80% of the respondents (176/219) report at least some level of product innovation; a little over 20% mentioned that they have innovated a lot. From the utilizable responses we could not find any relationship between the level of product innovation and the sector of activity or the level of exports.

As for the productive process, 43 out of 210 (around 20%) of the surveyed firms state that they had not introduced any kind of innovation whatsoever. Out of these 43, 25 are in the retail sector. In this case we noted a relationship between the level of innovation in the productive process and the sector of activity: manufacturing firms tend to state higher levels of innovation than other sectors with retail showing the lowest levels. Almost all the firms said they had introduced changes in their organizational systems, to a greater (106) or lesser (108) degree (214/234). In marketing, around 75% of the respondents mention some kind of innovation, usually at a medium level (mode 3 in a 5-point scale, 28.2%).

Later in the survey, respondents were also asked whether they considered their firm to innovate (in general terms). Around 70% (170/234) said they did. Of these, 164 chose some sources of innovation from a given list. The two most frequently chosen sources were Following the trends in other markets or firms (134 times) and Following their own ideas (115 times ). The least chosen was Keeping in touch with universities (23 times) denoting that universities are not generally seen as sources of innovation or at least as resources that SMEs could resort to. However, in a more refined analysis it is interesting to note that this item has some relevance within the manufacturing sector as it has received 12 mentions from 73 industrial firms.

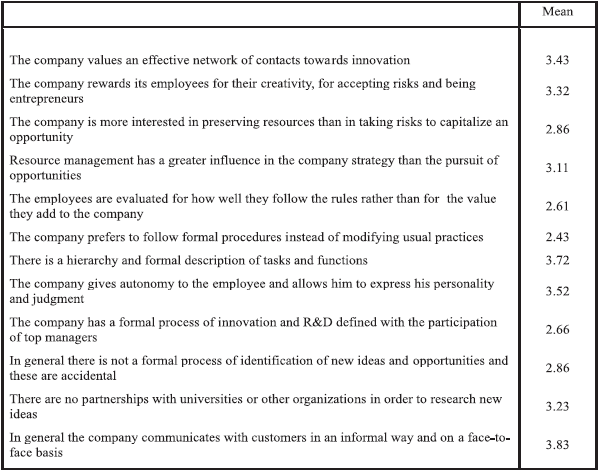

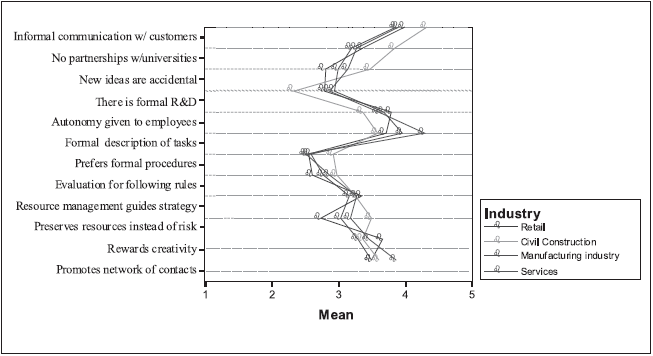

Considering that innovation stems from the level of fit and alignment of a company strategy, culture, technology and structure, we asked participants to indicate their level of agreement on a scale of 1 (absolutely disagree) to 5 (absolutely agree) with a series of statements about their own company in order to understand whether internal processes in the surveyed companies were likely to promote innovation. Table 3 below presents these results:

TABLE 3 – The company and innovation

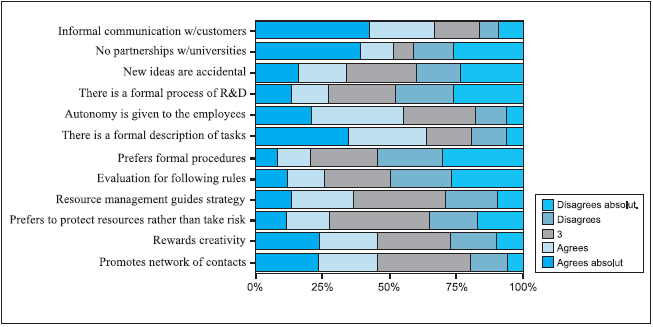

The mean scores show that, in general, respondents tend view their enterprise as innovation-oriented. There is however a gap between this thought and the results of other parts of the questionnaire as described above. Whether this is a constructed idea, a halo effect or an indication that innovation may be emerging is a matter that deserves further, more in-depth research. Such research would also help devise the meaning that each statement has for the different respondents, that is, how it can be interpreted. In fact the comparatively high score on the statement There is a hierarchy and formal description of tasks and functions may be indicative of a hostile environment to innovation but the lowest mean score (2.43) given to the statement The company prefers to follow formal procedures instead of modifying usual practices points in the opposite direction. The graph below, showing the percentages of individual scores, finetunes these results. We may see for example that the first, sixth and seventh statements refer to formality but while there is a convergence between the first and the sixth, the seventh sharply diverges. How can we be sure that respondents ascribe a somehow similar meaning to these statements? Another observation is that respondents quite often select extreme values in the scale and it is the combination of these extreme values that generates a mean close to the middle score and not the choice of scores close to the middle. Besides expressing a high standard deviation, this may be an indication that some thought was given to the statements before opinions were expressed.

Graph 1: The enterprise and innovation – score percentage

The graph below shows that, surprisingly, a sector analysis follows the same trends throughout the different statements in spite of the dissimilarities among industries. The greatest discrepancy is registered in the statement Prefers to preserve resources rather than to take risks between civil construction and retail.

Graph 2: The enterprise and innovation – mean scores by industry

Formalization of tasks is more obvious in the service sector (mean score 4.15) but, paradoxically, more than half of the respondents agreed that their company granted autonomy to the employees allowing them to express their personality and judgment. This again brings the question of meaning, i.e. what each statement means to different respondents and whether or not respondents are looking for the right answer.

FINDINGS ON COMPETITIVENESS AND STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

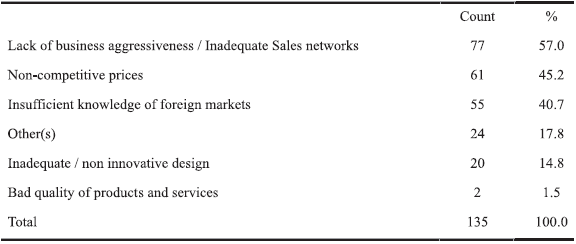

The survey shows that 57.7% of the respondents consider their products to be competitive abroad. Most of these (52%) are in the manufacturing industry. When enquired on the main reasons that hinder their companies from increasing their export turnover, respondents gave the answers shown in the table below. Lack of business aggressiveness or inadequate sales networks (57%) seem to be the main reason, followed by lack of price competitiveness (45.2%) and insufficient knowledge of foreign markets (40.7%).

Table 4 – Reasons hindering SMEs from increasing their export turnover

One section of the survey was devoted to enquiring on strategy development and on the main variables that respondents thought of when designing their strategy. Half of the companies surveyed (123) claimed they thought only in regional and/or national terms with 44 thinking only regionally. A mere 20% stated that they planned internationally. When we consider that our sample is drawn from a database of the 2500 largest SMEs in Portugal, we cannot but conclude that there is a huge way to go to push Portuguese SMEs into going international.

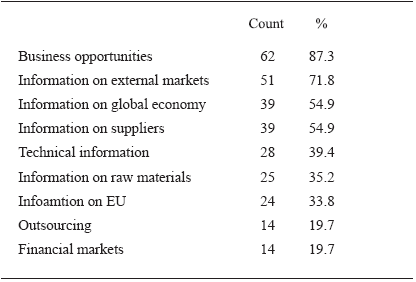

Asked about the variables that should be considered in the analysis of the environment when designing their strategy, respondents mentioned (i) the dynamism of competitors, (ii) the stability of institutions and of the economy; (iii) competitors market share; and (iv) the state of technology and availability of skilled labor. Many respondents (53.2%) declared they had conditions to conduct a correct analysis of the external environment with a similar figure (57.3%) considering that available information is sufficient for their needs. We did not observe any significant link between these assertions and the sector companies operate in. Out of the 109 who declared the opposite, 67 (61.5%) gave the lack of information as the main hindrance. Table 5 below shows the areas in which these respondents felt more information was needed (each respondent could mention more than one reason).

Table 5 – Items where information is most needed

Lack of information on business opportunities and suppliers are among the four most felt in all sectors of activity.

CONCLUSIONS AND LIMITATIONS

The results of our extensive questionnaire enable us to glean a clearer picture of Portuguese SMEs in a variety of issues including their export drive and international strategy. This picture is not very bright: half of them think only in regional or national terms with 35.7% of them thinking only regionally. The picture becomes even gloomier if we consider that our subjects are a sample from the 2,500 largest Portuguese SMEs.

From the literature review, the main factors that foster internationalization are, on the one hand, innovation and market adaptation and, on the other, knowledge of distribution and of communication channels. Only a minority of the respondent SMEs from our survey seem to be oriented to developing these resources that can foster their internationalization. According to the respondents this seems to be due not to an inability to conduct a correct analysis of the external environment or even to lack of information (only 67 firms mentioned this problem) but rather to structural problems that limit the surveyed companies in their ambition. One example is how respondents feel towards the Spanish market and Spanish companies.

Confronting this situation with internationalization requirements, we may say that Portuguese SMEs need to improve their strategies and internal capabilities for going abroad. Some aspects might give some hope like for example the results on innovation: in some cases the surveyed companies seem to have internal processes that foster innovation but, as noted, there are paradoxes and a broad standard deviation in the answers that recommend a better understanding of this issue.

The present study aimed to give a descriptive presentation of some of the data collected through an extensive survey. We concentrated on internationalization because in a small country like Portugal, with a small economy and open borders, going international is an imperative and should not be the prerogative of large companies alone. Moreover, international expansion of SMEs has been a growing trend for the past 20 years and many have been observed to internationalize at very early stages (Karagozoglu & Lindell, 1998; Pangarkar, 2008; Prater & Ghosh, 2005) . Internationalization provides learning opportunities, and SMEs can surely learn in the process but, as Qian (2002) noted, SMEs should be aware that they may have to undergo significant organizational changes in order to profit from these opportunities. Technological development, quality concerns, market awareness, branding and financing are among the managerial aptitudes SMEs need to develop.

This paper is only the first of a series we intend to complete on this subject. At this stage our research still has many limitations: we need to have a more in depth understanding of the reasons underlying the paradoxes and pitfalls of our findings, that is, taking this survey as a starting point, we need to supplement it with qualitative, fine-tuning research. We also need to establish more and deeper relationships with and within our data to better understand not only our sample but also how it relates to the larger population. This is what we plan to do since, constrained by limited resources and a constricted ambition, SMEs need the help of academics and researchers to pull through.

NOTE

[1]IAPMEI – Instituto para o Apoio às Pequenas e Médias Empresas Industriais

REFERENCES

Baird, I. S.; Lyles, A. M. & Orris, J. B. (1994), "The Choice of International Strategy by Small Business". Journal of Small Business Management, 32(1), pp. 48-59.

Bauman, Z. (1998), Globalization: The Human Consequences. New York, Columbia University Press.

Brouthers, L. E. & Nakos, G. (2005), "The role of systematic international market selection on small firms' export performance". Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), pp. 363-381.

Buckley, P. J. (Ed.) (1999), Foreign Direct Investment by Small and Medium Sized Enterprises: The Theoretical Background. NY, International Thomson Business Press.

Calof, J. L. (1993), "The impact of size on internationalization". Journal of Small Business Management, 31(4), 60-69.

Chandler, A. (1990), Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Claessens, S. & Schmukler, S. L. (2007), "International Financial Integration through Equity Markets: Which Firms from Which Countries Go Global?" IMF Working Paper, WP/07/138.

De Chiara, A. & Minguzzi, A. (2002), "Success factors in SMEs' internationalization process: an Italian investigation". Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2), pp. 144-153.

Gabrielsson, M. & Kirplanni, V. H. M. (2004), "Born globals: how to reach new business space rapidly". International Business Review, 13, pp.555-571.

Gadenne, D. (1998), "Critical Success Factors for Small Business Management, an Inter Industry Comparison". International Small Business Journal, 17(1), pp. 36-56.

Guburro, G. & O'Boyle, E. (2003). "Norms for evaluating economic globalization". International Journal of Social Economics, 30 (Retrieved from www.emeraldinsight.com).

IAPMEI (2008), Estudos e Informação Económica. Retrieved May, 29, 2008, from http://www.iapmei.pt/iapmei-art-03.php?id=2049 .

Karagozoglu, N. & Lindell, M. (1998), "Internationalization of small and medium-sized technology based firms: An exploratory study". Journal of Small Business Management, 36(1), pp. 44-59.

Knight, G. (2000), "Entrepreneurship and Marketing Strategy: The SME under Globalization". Journal of International Marketing, 8(2), pp. 13-32.

Lee, J. & Maniam, B. (2007), "Small business and globalization". The Business Review, Cambridge, Summer, 7(2), pp. 15-21.

Lu, J. W. & Beamish, P. W. (2001), "The internationalization and performance of SMEs". Strategic Management Journal, 22(6/7), pp. 565-584.

Mughan, T. & Lloyd-Reason, L. (2007), "Building the international sme across national settings: a global policy enquire and response". The Business Review, Cambridge, December, 9(1), pp. 127-133.

Mundim, A. P. F.; Alessandro, R. & Stochetti, A. (2000). "SMEs in global market: challenges, opportunities and threats". Brazilian Electronic Journal of Economics, 3(1). [ Links ]

OECD (2004), Facilitating SMEs Access to International Markets. Paper presented at the Promoting Entrepreneurship and Innovative SMEs in a Global Economy.

Oviatt, B. M. & McDougall, P. P. (1994), "Towards a theory of international new ventures". Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), pp. 45-64.

Oviatt, B. M. & McDougall, P. P. (Eds.) (1999), A Framework for Understanding Accelerated International Entrepreneurship, vol. 7, pp. 23-40. Stamford, CT, JAI Press.

Pangarkar, N. (2008), "Internationalization and performance of small-and medium-sized enterprises" Journal of World Business, doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2007.11.009.

Prater, E. & Ghosh, S. (2005), "Current operational practices of U.S. small and medium-sized enterprises in Europe". Journal of Small Business Management, 43(2), pp. 155-169.

Qian, G. (2002), "Multinationality, product diversification and profitability of emerging US small and medium sized enterprises". Journal of Business Venturing, 17, pp. 611-633.

Santos António, N. & Trigo, V. (1991), Pequenas Empresas – Sucessos e Insucessos. Lisboa, Edições Sílabo.

Westead, P.; Wright, M. & Ucbasaran, D. (2001), "The Internationalization of new and small firms: a resource-based view". The Journal of Business Venturing, 16, pp. 333-358.

Winch, G. & Bianchi, C. (2006), "Drivers and dynamic processes for SMEs going global". Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1), pp. 73-88.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Management Research Center (MRC) of ISCTE that enabled us to undertake this research. We also thank ISCTE-IULs Quantitative Methods Research Center (Giesta), Fernanda Pinheiro and Diana for their extensive expert cooperation preparing the data for analysis .

*Virgínia Trigo

Doutorada pelo ISCTE-IUL e Professora Auxiliar do ISCTE em Empreendedorismo/Departamento de Gestão do ISCTE

PhD in Management (ISCTE-IUL – Lisbon University Institute), Professor in Management Department at ISCTE-IUL – Lisbon University Institute.

**Teresa Calapez

Doutorada em Métodos Quantitativos (ISCTE-IUL), Professora Auxiliar na área da Análise de Dados/Departamento de Métodos Quantitativos do ISCTE-IUL.

PhD in Quantitative Methods (ISCTE-IUL – Lisbon University Institute), Professor in Quantitative Methods Department at ISCTE-IUL – Lisbon University Institute.

***Maria da Conceição Santos

Doutorada pelo IAEdAix-Marseille III, França e Professora Auxiliar do ISCTE-IUL em Marketing/Departamento de Gestão do ISCTE.

PhD in Management (IAEdAix-Marseille III, France), Professor in Management Department at ISCTE-IUL – Lisbon University Institute.