Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 0874-2049

Psicologia vol.29 no.1 Lisboa jun. 2015

Empowering Employees: A Portuguese Adaptation of the Conditions of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II)

Empowerment dos colaboradores: Adaptação portuguesa do Questionário Conditions of Work Effectiveness (CWEQ-II)

Alejandro Orgambídez-Ramos1,*, Gabriela Gonçalves1, Joana Santos1, Yolanda Borrego-Alés2, María Isabel Mendoza-Sierra2

1 Universidade do Algarve

2 Universidad de Huelva, Espanha

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to adapt and translate into Portuguese the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II) (Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian, & Wilk, 2004). A process of translation and reverse-translation was applied to the questionnaire's items, whose psychometric properties were examined using a sample of 282 Portuguese university employees, teachers and services staff. The data were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis, item analysis and reliability analysis. Criterion-related validity was analyzed using a multiple regression model on global empowerment and t-test. The results confirmed the original, four-factor structure obtained by Laschinger and colleagues (2004), supporting Kanter's structural empowerment theory. The psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the CWEQ-II were adequate, supporting the use of this questionnaire in the workplace. Future research should investigate its construct validity and test the nomological network of the operationalized construct within the field of psychological well-being and in the context of the workplace.

Keywords: Structural empowerment; Scale; Psychometric validation; University.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste estudo foi a tradução e adaptação para a população portuguesa do Questionário de Condições para Eficácia do Trabalho (Conditions of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire, CWEQ-II) (Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian, & Wilk, 2004). Foi aplicado um processo de tradução-retradução dos itens do questionário, cujas características psicométricas foram analisadas através de uma amostra de 282 funcionários, docentes e não docentes, de uma universidade portuguesa. Os dados foram submetidos a uma análise fatorial confirmatória, análise de itens e análise de fidelidade. A validade critério foi analisada com recurso a um modelo de regressão múltipla no empowerment global e a t-test. Os resultados confirmaram a estrutura original de quatro fatores, obtida por Laschinger e colaboradores (2004), a qual é suportada pela teoria de empowerment estrutural do Kanter. As propriedades psicométricas da versão portuguesa do CWEQ-II foram adequadas, permitindo a sua utilização no local de trabalho. Pesquisas futuras devem investigar a validade de constructo e testar a rede nomológica da construção, operacionalizada dentro do campo do bem-estar e no contexto do local de trabalho.

Palavras-chave: Empowerment Estrutural; Escala; Validação psicométrica; Universidade.

Interest in the study of empowerment in the workplace has grown within organizational psychology and business context as new challenges have come to necessitate innovative, competitive employees (Ertuk, 2010; Ferreira, Caetano, & Neves, 2011). Empowerment is evidenced by organizational members who are inspired and motivated to make meaningful contributions and who have the confidence their contributions will be recognized and valued (Joo & Lim, 2013; Laschinger, Wilk, Cho, & Greco, 2009; Randolph & Kemery, 2011).

The influence of context in manifestations of empowerment makes it a challenge for researchers to assess it. In this sense, an understanding of the work context that facilitates empowerment has important theoretical and practical implications. The Conditions of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II) (Laschinger et al., 2004), based on Kanter's structural empowerment theory (Kanter, 1993), allows the measurement of organizational characteristics that foster empowerment in the workplace. As there is no adaptation of this instrument for the Portuguese language, the aim of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the Portuguese adaptation of the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II).

Structural empowerment

The new socio-economic and work environments in Portugal and Europe have required a collective effort from business organizations to improve their competitiveness and the quality of their services and products (Mendoza-Sierra, León-Jariego, Orgambídez-Ramos, & Borrego-Alés, 2009). Empowerment has proved to be a powerful tool contributing to workers' wellbeing and companies' productivity (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013; Mendoza-Sierra, Orgambídez-Ramos, León-Jariego, & García-Carrasco, 2014). Consequently, it becomes essential to know how a company determines what should be done in order to increase employee perception of empowerment (Matthews, Diaz, & Cole, 2003).

Due to the varying perspective on empowerment within the business context, several definitions of empowerment have been produced (Koberg, Boss, Senjem, & Goodman, 1999; Mendoza-Sierra et al., 2009; Randolph & Kemery, 2011). According to Spreitzer (1995), two general perspectives of empowerment can be distinguished: the relational perspective and the psychological perspective.

The psychological perspective of empowerment focuses on the employee's perception of empowerment (Spreitzer, 1995; Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). From this perspective, empowerment is achieved only when psychological states produce a perception of empowerment within the employee (Matthews et al., 2003; Mendoza-Sierra et al., 2009; Spreitzer, 1995). Empowerment is defined as the psychological state workers should experience when management provides them with an appropriate level of power and control (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013; Spreitzer, 1995).

Relational empowerment has been referred to top-down processing (Conger & Kanungo, 1988) as well as mechanistic (Matthews et al., 2003). It is the belief that empowerment occurs when higher levels within a hierarchy share power with lower levels within the same hierarchy (Seibert, Wang, & Courtright, 2011). From this perspective, empowerment is also considered as a series of activities and practices that, when carried out, gives subordinates power, control, and authority. According to this view, empowerment implies organizations guarantees employees will receive information, will have the knowledge and skills to contribute to goal achievement, will have the power to make fundamental decisions, and will be rewarded based on organizational outcomes (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013). This type of empowerment has been termed structural empowerment (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013; Kanter, 1993; Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian, & Wilk, 2001; Laschinger et al., 2004). Interest in structural empowerment has led to the development of several scales that are intended to assess levels of empowerment in the organizations: Workplace Empowerment Scale (Spreitzer, 1995), Leader Empowering Behavior Questionnaire (Konczak, Stelly, & Trusty, 2000), and Organizational Empowerment Scale (Matthews et al., 2003). However, only Kanter (1993) offers a theoretical framework, empirically supported, for creating empowering and meaningful work and organizational environments for professionals.

According to Kanter (1993), workers are empowered when they perceived that their work environment provides opportunity for growth and access to power required to carry out job demands. Kanter (1993) defines power as an ability to mobilize resources and achieve goals, as opposed to the notion of power in the traditional hierarchical context. Jobs that provide discretion and are central to the organizational purposes increase access to these empowering structures. Similarly, strong networks with peers, superiors, and other organizational members increase access to these resources (Armstrong, Laschinger, & Wong, 2009; Laschinger et al., 2004). These systematic conditions, labeled as formal and informal power by Kanter (1993), influence empowerment, which results in increased work effectiveness. Thus, power is related to autonomy and mastery, instead of domination and control, and maximizes the power enjoyed by each member of the organization (Armstrong et al., 2009). Structural empowerment has been linked to important outcomes such as job satisfaction, perceived control over nursing practice, engagement, and lower levels of job stress (Armstrong et al., 2009; Laschinger, Wong, & Grau, 2013; Lautizi, Laschinger, & Ravazzolo, 2009; Wong & Laschinger, 2013).

The Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire

Kanter's theory of structural empowerment is the theoretical framework on which the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (Laschinger et al., 2001; Laschinger et al., 2004) is based. High levels of structural empowerment come from access to opportunity, support, information, and resources.

Access to opportunity refers to the possibility of growth and movement within the organization as well as the opportunity to increase knowledge and skills. Specifically, Kanter (1993) referred to opportunity as the ability to advance in the organization through connections, exposure, and visibility or the ability to learn and grow professionally from a job. Access to resources relates to one's ability to acquire the financial means, materials, time, and supplies required to do the work.

Access to information refers to having the formal and informal knowledge that is necessary to be effective in the workplace (technical knowledge and expertise required to accomplish the job and an understanding of organizational policies and decisions). Having information allows an employee to make decisions and to act quickly, as well to pass on information to other employees to complete more (Gilbert, Laschinger, & Leiter, 2010). Finally, access to support involves receiving feedback and guidance from subordinates, peers, and superiors. It refers to an employee's ability to take non-ordinary and risk-taking action response to situations without having to pass through organizational "red tape" (Kanter, 1993).

Access to empowerment structures is enhanced by formal power and informal power. Formal power is derived from specific job characteristics such as flexibility, adaptability, creativity associated with discretionary decision-making, visibility, and centrality to organizational purposes and goals. On the other hand, informal power is derived from social connections and the development of communication and information channels with sponsors, peers, subordinates, and cross-functional groups (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger et al., 2001; Laschinger et al., 2004).

The Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ) was designed to measure these four empowerment dimensions. Items were derived from Kanter's original ethnographic study of work empowerment and modified by Chandler (1986) for use in a nursing population. The CWEQ-II is a modification of the original developed by Laschinger et al. (2004). The CWEQ-II has been frequently studied and used in nursing research since 2000 and has shown consistent reliability and validity (Seibert et al., 2011; Wallace, Johnson, Mathe, & Paul, 2011).

The CWEQ-II is made up of 12 items distributed into four sub-scales, each measuring perceived access to a corresponding empowerment structure (Laschinger et al., 2004): (a) support, (b) resources, (c) information, and (d) opportunity. To compute one's total level of structural empowerment, the average scores on each subscale is calculated, so that highest scores correspond to high perceived structural empowerment. Several studies have shown Cronbach's alpha coefficients from .70 to .95 in the four sub-scales (Laschinger et al., 2009; Laschinger et al., 2013; Lautizi et al., 2009; Wong & Laschinger, 2013).

The CWEQ-II has been translated only to Spanish by Jáimaz and Bretones (2013), with a sample of 164 workers. Using confirmatory factor analysis, they found that the best fit-model was the one originally proposed by Laschinger et al. (2004): four subscales with three items (opportunity includes items 1, 2, and 3; information includes items 4, 5, and 6; support includes items items 7, 8, and 9; resources includes items 10, 11, and 12). In the study carried out by Jáimaz and Bretones (2013), all the subscales expressed a good reliability, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranging from .71 to .80.

The aim of this study was to adapt and validate the CWEQ-II in Portugal. The main reason for this study was the absence of Portuguese scales that measure structural empowerment, making it impossible to study in Portuguese-speaking populations. Also, the context of the Bologna innovative teaching involving University staff requires to explore and analyze the organizational structures that empower both teachers and services staff.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 282 University employees from a Portuguese public university. As for sample's sociodemographic characteristics, 63.8% were women. The average age of the sample was 47.78 years (SD = 8.04). Most of the sample was married (68.1%). Respondents were fairly distributed by professional category: 53.9% were teachers and 46.1% were services staff.

Measures

Sociodemographic data registry

Information was collected on age, sex, years at the university, and university department or service.

Structural empowerment

To measure structural empowerment, we used the CWEQ-II (Laschinger et al., 2004) described above. The CWEQ-II consist of 12 items distributed into four sub-scales: access to opportunity (items 1, 2, and 3), access to information (items 4, 5, and 6), access to support (items 7, 8, and 9), and access to resources (items 10, 11, and 12). Responses were given on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means "None" and 5 means "A lot". Scores of reliability on the CWEQ-II have ranged from .70 to .95 (Laschinger et al., 2009; Laschinger et al., 2013; Lautizi et al., 2009; Wong & Laschinger, 2013). In the process of adaptation, we solicited the authorization of the original questionnaire's author, which it was duly granted.

Global empowerment

The CWEQ-II includes a global measure of empowerment (GE) as a validation index (Laschinger et al., 2004). The GE score is obtained by summing and averaging the two global empowerment items. Score range is between 1 and 5, where 1 means "None" and 5 means "A lot". Higher scores represent stringer perceptions of working in an empowered work environment.

Procedure

The first step in conducting this study was to back-translate the items of the CWEQ-II into Portuguese in accordance with Hambleton, Merenda, and Spielberger's (2006) recommendations. We first sought the collaboration of three university professors in the field of human resources and organizational psychology that did not participate in the study. They translated the questionnaire from English to Portuguese independently of one another. We subsequently compared the three translations and debated the differences between them until reaching a consensus about each item, thereby obtaining a single version of each in Portuguese.

The next step was to translate the Portuguese version obtained from the original questionnaire back into English. This process was done by a professional translator whose first language was English and who was not involved in the first translation. We later compare the two English versions; the original and the translation of the Portuguese version, analyzed the translation's quality by seeing what items coincided in the two questionnaires, making modifications when necessary (Hambleton et al., 2006).

To analyze the validity of the newly Portuguese questionnaire, each item was evaluated by expert judges (Balluerka, Gorostiaga, Alonso-Arbiol, & Haramburu, 2007). The participation of three experts, two of the construct being assessed, and one in scale construction, was requested to analyze the questionnaire.

In order to effectively conduct the assessment, the experts were provided with the concept of structural empowerment, along with the dimensions that comprise it. They were subsequently given a list of all the items and the judges' task was to classify each into the dimension to which they thought it belonged. They were asked to give their opinions on whether the number of items was sufficient to measure each dimension. Finally, they were asked to evaluate if the items were written clearly (Balluerka et al., 2007). The resulting expert judgement yielded very favourable results in that all three judges correctly classified all items. They furthered decided that the dimensions could be perfectly measured by three items.

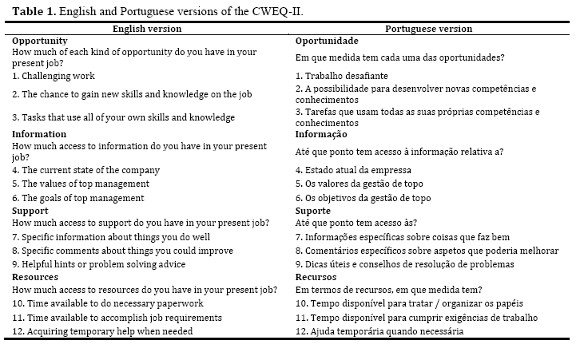

The outcome of the steps described above was the Portuguese version of the CWEQ-II, consisting of 14 items including 3 for each dimension: support, resources, information, and opportunity; and 2 for the global measure of empowerment. Table 1 presents the English version as well as the Portuguese version.

Once the CWEQ-II was brought to Portuguese, we proceeded to data collection in the university. The CWEQ-II was administered between February and June 2013. All the participants were informed of the study's objective and the confidentiality of their data, and gave informed consent.

Data analysis

The statistical package STATA 12.0 was used to carry out the data analyses. The psychometric properties of the CWEQ-II were explored through item analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, internal consistency, and criterion validity. For the treatment of missing data, we decided to simply omit those cases and run the analyses on what remains. Although list wise deletion often results in a substantial decrease in the sample size available for the analysis, it has important advantages. In particular, under the assumption that data are missing completely at random, it leads to unbiased parameter estimates (Cohen, 1988).

Item analysis

Means, standard deviations, and skewness were calculated for each item that was used to measure structural empowerment, as well as for the subscales and the total score of the CWEQ-II.

Confirmatory factor analysis

To test the structure of the Portuguese version of the CWEQ-II, confirmatory analyses were performed. The maximum likelihood method of estimation was utilized, which assumes multivariate normal distribution, and it is robust when this assumption is not met (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003). In order to address the issue of multivariate non-normality, Jackknife Repeated Replication (JRR) was conducted to estimate the sampling variability of all statistics presented. This robust variance estimator takes into account sampling variability that arises due to the imprecision in the measurement of individual proficiencies as well as sampling variability resulting from the features of the sample design (Berger, 2007).

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the scale was further investigated by Cronbach's alpha coefficients, corrected item-total correlations and reliability when each item is removed. Also shown is the discrimination (Delta index) of the instrument when each item is deleted.

Predictive validity

Predictive validity was analyzed using a multiple regression model, with the global empowerment score as the dependent variable and the four sub-scales of the CWEQ-II as the independent variables. Finally, to carry out comparisons between teachers and services staff on structural empowerment, a t-test for independent samples was used.

Results

Item analysis

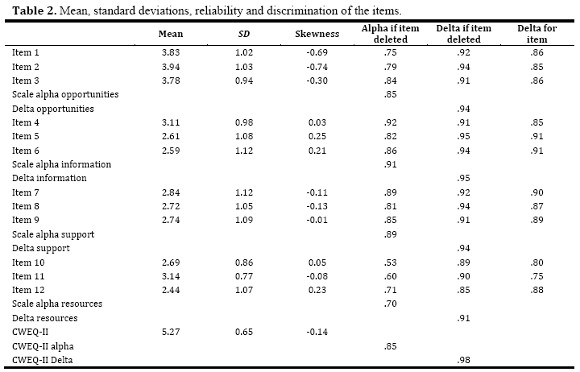

The mean score on the five-point Likert-type scale used to assess structural empowerment ranged from 2.44 to 3.94. None of the items had absolute skewness greater than one. Although the distribution was slightly negative skewed, most of the scores revealed a reasonably normal distribution (see Table 2).

Confirmatory factor analysis

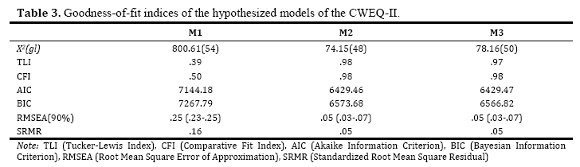

Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), three different models are tested. The first model (M1) assumes that all items of the scale load on one common factor ("structural empowerment") and, therefore, that the four dimensions cannot be differentiated. The second model (M2) assumes four correlated factors that represent access to opportunities, information, support, and resources. Finally, the third model (M3) specifies a model with a one general second-order factor, an underlying factor to the four factors.

First, we examined whether the assumption of multivariate normality of the data was satisfied. Using the STATA macro developed by Baum and Cox (2007), we found that the majority of the skewness and kurtosis values were significant and the Mardia's measures of multivariate kurtosis and skewness were 185.73 and 16.51 (p < .01), respectively. Also, the Dooknik-Hansen test (Doornik & Hansen, 2008) rejected the null hypothesis of multivariate normality (p < .01). These results suggest deviations from normality and, for that reason, we decided to employ maximum likelihood with Jackknife Repeated Replication (Berger, 2007) in the confirmatory factor analyses. In addition, because of the particular method of estimation adopted, the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), AIC (Akaike Information Criterion), BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), and SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) indices were used. Generally, for CFI and TLI a value close to .95 indicates a model with a good fit; for the SRMR and the RMSEA values less than .08 indicate an adequate fit. Regarding AIC and BIC measures, they are comparative measures of fit and so they are informative only when two or more different models are estimated. Lower values indicate a better fit. The model with the lowest AIC and BIC is the best fitting model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Table 3 presents the fit statistics for the different proposed models.

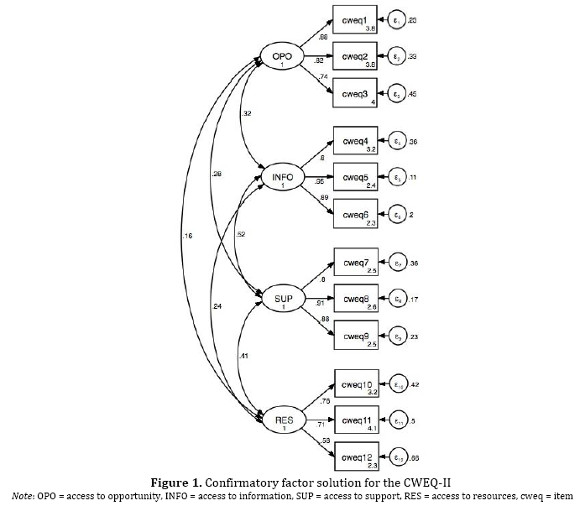

The results showed that M1 was the worth fitting model, with all the fit indices out of the acceptable range. For M2 (c2/gl = 1.54, TLI = .98, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05) and M3 (c2/gl = 1.56, TLI = .97, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05), all fit indices were within the standard recommended range, suggesting that both models properly fit the data. AIC and BIC measures of M2 and M3 were similar, so M2 seems more preferable since it is closer to the original version and the Spanish translation.

Internal consistency

Table 2 shows item reliability and discrimination for the CWEQ-II. Also shown are the reliability and discrimination of the instrument when each item is removed. The results showed that Cronbach's alpha coefficients were .85 to the opportunity subscale, .91 for the information subscale, .89 for the support subscale, and .70 for the resources subscale, and the .85 for the global CWEQ-II. The mean inter-item correlation coefficients for the CWEQ-II was .52, while the corresponding values for opportunity, information, support, and resources were .44, .62, .64 and .38, respectively. All values were within the acceptable recommendation range for multifactor scales (Briggs & Cheek, 1986).

With regards to discrimination, the Delta coefficients of the CWEQ-II's items ranged from .80 to .91. The CWEQ-II Delta coefficient (Delta = .98) indicated that the instrument was discriminating, with 98% of possible discrimination being made. This value is adequate according to Ferguson (1949), who indicates that a normal distribution would be expected to have discrimination of Delta > .90. On this basis, the CWEQ-II showed good discrimination (Ferguson, 1949; Hankins, 2007).

Predictive validity

To analyze predictive validity, regression model was used to assess the ability of access to opportunity, support, information, and resources to predict levels of global empowerment in the workplace. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity. The total variance explained by the model was 26%, F(4, 221) = 18.71, p < .01. All the sub-scales of the CWEQ-II were statistically significant: access to opportunity (ß = .24, p < .01), access to information (ß = .12, p < .01), access to support (ß = .17, p < .01), and access to resources (ß = .21, p < .01).

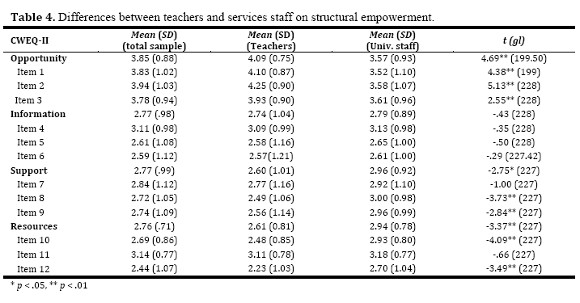

With regards to the differences between teachers and services staff on structural empowerment (see Table 4), we observed that teachers scored higher than service staff on access to opportunities (p < .05): "challenging work" (item 1), "the chance to gain new skills and knowledge on the job" (item 2) and "tasks that use all of your own skills and knowledge" (item 3). On the other hand, services staff scored higher than teachers on access to support and access to resources (p < .05): "specified comments about things you could improve" (item 8), "helpful hints or problem solving advice" (item 9), "time available to do necessary paperwork" (item 10), and "acquiring temporary help when needed" (item 11). There were no statistical significant differences on the rest of items between teachers and services staff.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to contribute to the adaptation of the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWEQ-II) in the Portuguese context. This questionnaire showed good psychometric properties. Confirmatory factor analysis, Cronbach's alpha coefficients and discrimination indexes (Delta), and predictive validity supported the internal validity and reliability of the questionnaire.

Our findings revealed that the original structure of the questionnaire was also replicated in the Portuguese context; however, the structure of a general second-order factor showed very similar indices to the observed ones in the original structure of four factors. Consequently, we decided to adopt the four-factor model since it is consistent with the original model (Laschinger et al., 2001, 2004) and the observed model in the Spanish adaptation of the CWEQ-II (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013). However, new studies would be necessary to verify which of the two factor structures is best suited. Considering the feasibility and the statistical significance of all parameter estimates and the substantial good fit of the model, we can conclude that the four-factor model presents a good overall fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

With regard to the internal consistency, adequate indices of reliability were observed (Briggs & Cheek, 1986), which were similar to the ones obtained by Laschinger and colleagues (Laschinger et al., 2009, 2013; Lautizi et al., 2009; Wong & Laschinger, 2013) and the ones observed in the Spanish version of the CWEQ-II (Jáimaz & Bretones, 2013). Regarding test discrimination, the CWEQ-II showed good discrimination based on the suggestions made by Ferguson (1949) and Hankins (2007, 2008).

The predictive validity was supported by the multiple regression model's results, with the global empowerment score as the dependent variable and the four subscales of the CWEQ-II as the independent variables. Our results suggest that access to opportunity, information, resources, and support significantly contribute to employees' perception of structural empowerment, giving support to the relationships between structural empowerment dimensions and global empowerment (Gilbert et al., 2010; Laschinger et al., 2001, 2004, 2013). The observed relationship between structural and global empowerment supports Kanter's theory about empowerment in the workplace. She argues that organizational factors in the workplace are crucial conditions for empowering employees to accomplish their work (Kanter, 1993; Laschinger et al., 2001, 2004).

The results of this study suggest that access to information, support, resources, and opportunity would create the psychological state that employees must experience for managerial interventions to be successful (Laschinger et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2011). Access to opportunity refers to the possibility of growth and movement within the organization as well as the opportunity to increase knowledge and skills. A work context that offers opportunities to increase knowledge and skills is a relevant motivational factor, but only if there is an adequate person-job fit (Kanter, 1993). Workers should perceive that they have access to the necessary resources and information to perform their tasks. Furthermore, employees should have access to the financial means, materials, time, and supplies, as well as an understanding of organizational policies and decisions, and the technical and expert knowledge required to perform the job. In addition, the more feedback and guidance from supervisors, peers, and customers, the higher levels of job satisfaction. Access to these structures fosters employees' empowerment, developing a sense of meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact (Laschinger et al., 2013; Spreitzer, 1995; Wong & Laschinger, 2013).

Differences between teachers and university staff in structural empowerment levels have been observed. Teachers perceived more access to opportunities in the workplace while services staff scored higher on access to support and access to resources. These results might indicate different workplace perceptions and job characteristics. Teachers could experience that they have more autonomy, discretion to make their job, and opportunities to increase knowledge and skills, while university staff could perceive more support from superiors and peers, and more resources (e.g., time, information) to perform their work. Job characteristics and job demands and resources (e.g., feedback, autonomy, meaning) might explain the differences in the structural empowerment scores.

On a practical level, Kanter's structural empowerment theory provides a framework for understanding empowering workplaces and empowered employees. The CWEQ-II could be useful in designing organizational strategies for which empowering employees may be advantageous to improve the quality of services as well as increasing employees' well-being. Meanwhile, it is an easy-to-apply tool requiring minimal time to complete. However, it is necessary to take into account certain limitations that the study may have had. The sample was mainly comprised of only two differentiated groups of workers (teachers vs. services staff), so it would be necessary to test the scale with other groups of workers. In the same sense, new studies must be conducted and cultural adaptations should be made in other countries in order to verify the questionnaire's factor structure. Finally, it would be necessary to conduct further studies employing this instrument and analyzing its relationship to other organizational variables (e.g., organizational commitment, citizenship behaviours) so as to create the most complete conceivable representation of organizational relations.

References

Armstrong, K., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Wong, C. (2009). Workplace empowerment and magnet hospital characteristics as predictos of patient safety climate. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 24, 55-62. [ Links ]

Balluerka, N., Gorostiaga, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Haramburu, M. (2007). La adaptación de instrumentos de medida de unas culturas a otras: Una perspectiva práctica [Test adaptation to other cultures: A practical approach]. Psicothema, 19, 124-133. [ Links ]

Baum, C. F., & Cox, N. J. (2007). omninorm: Stata module to calculate omnibus test for univariate/multivariate normality. Boston, MA: Boston College Department of Economics, Statistical Software Components S417501.

Berger, Y. G. (2007). A jackknife variance estimator for unistage stratified samples with unequal probabilities. Biometrika, 94, 953-964. [ Links ]

Briggs, S. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1986). The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality, 54, 106-148. [ Links ]

Chandler, G. E. (1986). The relationship of nursing work environment to empowerment and powerlessness (Unpublished doctoral Dissertation). University of Utah, Utah. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2ª ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. The Academy of Management Journal, 13, 471-482. [ Links ]

Doornik, J. A., & Hansen, H. (2008). An omnibus test for univariate and multivariate normality. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 70, 927-939. [ Links ]

Ertuk, A. (2010). Exploring predictors of organizational identification: Moderating role of trust on the associations between empowerment, organizational support, and identification. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 19, 409-441. [ Links ]

Ferguson, G. A. (1949). On the theory of test discrimination. Psychometrika, 14, 61-68. [ Links ]

Ferreira, J., Caetano, A., & Neves, J. (2011). Manual de psicossociologia das organizações (3ª ed.). Lisboa: Escolar Editora. [ Links ]

Gilbert, S., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Leiter, M. (2010). The mediating effects of burnout on the relationship between structural empowerment and organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 339-348. [ Links ]

Hambleton, R. K., Merenda, P. F., & Spielberger, C. D. (2006). Adapting educational and psychological test for cross-cultural assessment. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Hankins, M. (2007). Questionnaire discrimination: (Re)-introducing coefficient Delta. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19, e1-e7. [ Links ]

Hankins, M. (2008). How discriminating are discriminative instruments? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 36, e1-e5. [ Links ]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1-55. [ Links ]

Jáimaz, M. J., & Bretones, F. D. (2013). Spanish adaptation of the structural empowerment scale. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16 , 1-7. [ Links ]

Joo, B. K. B., & Lim, T. (2013). Transformational leadership and career satisfaction: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20, 316-326. [ Links ]

Kanter, R. M. (1993). Men and women of the corporation (2ª ed.). New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Koberg, C. S., Boss, R. W., Senjem, J. C., & Goodman, E. A. (1999). Antecedents and outcomes of empowerment: Empirical evidence from the health care industry. Group & Organization Management, 24, 71-91. [ Links ]

Konczak, L. J., Stelly, D. J., & Trusty, M. L. (2000). Defining and measuring empowering leader behaviors: Development of an upward feedback instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 301-313. [ Links ]

Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2001). Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: Expanding Kanters model. Journal of Nursing Administration, 31, 260-272. [ Links ]

Laschinger, H. K. S., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2004). A longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empowerment on work satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 527-545. [ Links ]

Laschinger, H. K. S., Wilk, P., Cho, J., & Greco, P. (2009). Empowerment, engagement, and perceived effectiveness in nursing work environments: Does experience matter? Journal of Nursing Management, 17, 636-646. [ Links ]

Laschinger, H. K. S., Wong, C., & Grau, A. (2013). Authentic leadership, empowerment, and burnout: A comparison in new graduates and experienced nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 21, 541-552. [ Links ]

Lautizi, M., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Ravazzolo, S. (2009). Workplace empowerment, job satisfaction, and job stress among Italian mental health nurses: An exploratory study. Journal of Nursing Management, 17, 446-452. [ Links ]

Matthews, R. A., Diaz, W. M., & Cole, S. G. (2003). The organizational empowerment scale. Personnel Review, 32, 297-318. [ Links ]

Mendoza-Sierra, M. I., León-Jariego, J. C., Orgambídez-Ramos, A., & Borrego-Alés, Y. (2009). Evidencias de validez de la adaptación española de la organizational empowerment scale [Validity evidence of the Spanish adaptation of the organizational empowerment scale]. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 25, 17-28. [ Links ]

Mendoza-Sierra, M. I., Orgambídez-Ramos, A., León-Jariego, J. C., & García-Carrasco, A. M. (2014). Service climate as a mediator of organizational empowerment in customer-service employees. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, 1-10. [ Links ]

Randolph, W. A., & Kemery, E. R. (2011). Managerial use of power bases in a model of managerial empowerment practices and employee psychological empowerment. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 18, 95-106. [ Links ]

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23-74. [ Links ]

Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 981-1003. [ Links ]

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Managament Journal, 38, 1442-1465. [ Links ]

Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An interpretive model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15, 666-681. [ Links ]

Wallace, J. C., Johnson, P. D., Mathe, K., & Paul, J. (2011). Structural and psychological empowerment climates, performance, and the moderating role of shared felt accountability: A managerial perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 840-850. [ Links ]

Wong, C., & Laschinger, H. K. S. (2013). Authentic leadership, performance, and job satisfaction: The mediating role of empowerment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69, 947-959. [ Links ]

Alejandro Orgambídez-Ramos, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro (Portugal). E-mail: aoramos@ualg.pt

Recebido: 27/02/2014

Aceite: 06/04/2015

Publicado: 06/2015

Apoio à publicação: Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Ministério da Educação e Ciência, Portugal) – Programa FACC