Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Ex aequo

versão impressa ISSN 0874-5560

Ex aequo no.40 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22355/exaequo.2019.40.03

DOSSIER: GÉNERO E STATUS EM POLÍTICA INTERNACIONAL: DINÂMICAS DE COOPERAÇÃO, CONFLITOS E ATIVISMOS

Coordenação de Vânia Carvalho-Pinto e Andrea Fleschenberg

Gender quotas in Indonesia: Re-examining the role of international NGOs

Quotas de género na Indonésia: reexame do papel das ONG internacionais

Les quotas de genre en Indonésie: réexaminer le rôle des ONG internationales

Ella Syafputri Prihatini* and Wahidah Zein Br Siregar**

* PhD in Political Science and International Relations, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

** PhD in Political Science and International Relations, UIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya, Indonesia.

ABSTRACT

Women's political representation in Indonesia has been rather limited and has fluctuated since independence in 1945. In a hope to improve this situation, a legislated gender quota of 30 percent for candidates in Indonesia was first implemented in the 2004 elections. In this paper, we strive to answer the question of what is the role of international NGOs in helping the process of the provision of candidate gender quotas in Indonesia. By analysing literature on the importance of gender quotas from theoretical perspectives, examples on the implementation of quotas of other countries, role of NGO in democracy as well as in women political representation, and interviews with six participants from two Indonesian NGOs and two International NGOs, who were directly involved in the process of endorsing gender quotas, we found that the influence of international NGOs has been significant and yet indirect as the pursuit of affirmative action policy is only part of the bigger project in promoting gender equality.

Keywords: gender quotas, Indonesia, international NGOs, women's representation.

RESUMO

A representação política das mulheres na Indonésia tem sido bastante limitada e oscilou desde a independência em 1945. Na esperança de melhorar essa situação, uma quota de género de 30% dos candidatos foi implementada pela primeira vez nas eleições de 2004 na Indonésia. Neste artigo, esforçamo-nos para responder à pergunta sobre qual o papel das ONG internacionais no apoio ao processo de estabelecimento de quotas de género nas candidaturas eleitorais na Indonésia. Ao analisar a literatura sobre a importância das quotas de género a partir de perspetivas teóricas, de exemplos sobre a implementação de quotas noutros países, do papel das ONG na democracia e na representação política das mulheres, e de entrevistas com seis participantes de duas ONG indonésias e duas ONG internacionais que estiveram diretamente envolvidas no processo de estabelecimento de quotas de género, verificámos que a influência das ONG internacionais tem sido significativa, ainda que indireta, uma vez que a procura de políticas de ação afirmativa é apenas uma parte do projeto mais amplo de promoção da igualdade de género.

Palavras-chave: quotas de género, Indonésia, ONG internacionais, representação de mulheres.

RÉSUMÉ

La représentation politique des femmes en Indonésie a été plutôt limitée et a fluctué depuis l'indépendance de 1945. Avec l'espoir d'améliorer cette situation, un quota de 30% de femmes, prévu par la loi, a été mis en place lors des élections de 2004. Dans cet article, nous nous efforçons de répondre à la question de savoir quel est le rôle des ONG internationales dans le processus de mise en place de quotas de candidats par sexe en Indonésie. En analysant la littérature sur l'importance des quotas de genre du point de vue théorique, des exemples sur la mise en oeuvre de quotas d'autres pays, le rôle des ONG dans la démocratie ainsi que dans la représentation politique des femmes, et des entretiens avec six participants de deux ONG indonésiennes et deux internationales, qui ont participé directement au processus d'approbation des quotas de genre, nous avons constaté que l'influence des ONG internationales était importante et indirecte, la poursuite de la politique de discrimination positive n'étant qu'une partie du plus grand projet de promotion de l'égalité des sexes.

Mots-clés: quotas de genre, Indonésie, ONG internationales, représentation des femmes.

Introduction

The provision of gender quotas in Indonesia –the world's third-largest democracy– is in line with the global trend in adopting this affirmative action policy. The end of Suharto's New Order regime and the start of Reformasi in 1998 offered a huge window of opportunity for activists to pursue advocacy in women's rights, including in political representation (Bessell 2010). After a series of debates and negotiations, both inside and outside of parliamentary chambers, a 30 percent legislated candidate quota was introduced in 2003 and implemented for the first time in the 2004 elections.

While many studies have observed the progress of women's share in Indonesia's national Lower House (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/DPR) (Shair-Rosenfield 2012; Hillman 2017; Prihatini 2019a) and the process of introducing gender quotas (Siregar 2005; Soetjipto 2005), observations specifically related to the role of international actors remain limited. How have NGOs that are funded by international donors supported the process of the provision of legislated gender quotas? Is it pertinent to suggest that the introduction of gender quotas in Indonesia is a result of the diffusion of international norms related to gender equality? This paper aims to unravel these questions by re-examining the role of international NGOs in helping the promotion of gender quotas in the legislation process in Indonesia.

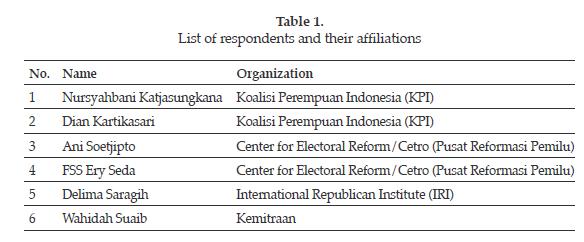

The data presented in this paper is a combination of a literature review and interviews which involved women's rights activists, former MPs and international NGO representatives. In total six participants have been interviewed (see Table 1). Four of them are from Indonesian NGOs: two from KPI (Koaliasi Perempuan Indonesia – Indonesian Women Coalition) and two from CETRO (Center for Electoral Reform). The other two are from International NGOs: one from IRI (Inter national Republican Institute) and one from Partnership. We chose these NGOs because of their involvement in the effort to increase women's political representation (see Siregar 2010). KPI and CETRO, even though they are national NGOs, have good relations with International NGOs or donor agencies. They have received some funds from these institutions to run their programs.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: a theoretical framework on the role of NGOs in democracy and in increasing representation of women in politics is in the first section; an overview of women's parliamentary representation in Indonesia, which elaborates on trends in nomination as well as in women's electability over the years; a section discussing findings from the literature review and interviews with respondents which are comprised of female activists, former MPs, and international NGO representatives; another section presents the remaining challenges in promoting women's political representation in a post-gender quotas environment, highlighting the enduring gaps in enhancing women's share in parliament. Conclusions and suggestions are discussed in the final section.

NGOs, Democracy, and Political Representation of Women

NGOs play an important role in democracy (Byers 2007; Suleiman 2013). Even in countries where democracy is missing, such as in China, NGOs try to find ways to practice democracy (Jacka 2010). Suleiman summarizes three typologies of relations between NGOs and democracy or good governance. In Europe, they work hand in hand with governments to formulate policies. Governments adopt a view that good cooperation among stakeholders of the country, the state apparatus, the market, and civil society can produce qualified and creative policies so that people can adapt well to the changes they face. In America, NGOs are viewed as independent organizations that help society come under less government control and that monitor government policies to ensure accountability. In developing countries, NGOs help governments to enact reform processes to strengthen democracy (Suleiman 2013, 245-246).

Obviously, not every effort made by NGOs can be successful. Some studies have provided evidence of the failure of NGOs either local, but supported by international agencies, or purely international in strengthening democracy in the countries where they work (Rahman 2006; Jacka 2010; Cumming 2011). Nevertheless, NGOs' role in democratization is pivotal as they are working in all its phases (Herrold 2016). Firstly, during the pre-transition period, NGOs serve as spaces of mobilization where opposition groups develop their platforms and recruit supporters. In the following phase, NGOs continue to act as mobilizing structures that also pressure and advise transitional government institutions to be more transparent and accountable to citizens. Lastly, in the democratic consolidation phase, NGOs pressure the state for further democratic reforms but also enter into the business of inculcating democratic values. Herrold (2016) further argues that NGOs are thought to voice various groups and interests in public, including women and other minority groups.

In her seminal work, Roces (2010) argues that the global expansion of civil society in the last 30 years has been exemplified by the proliferation of NGOs; for example, women's NGOs were prime actors in women's movements in many Asian countries. During the authoritarian government under Suharto's presidency, freedom of expression was extremely limited. However, international agreements strongly related to women's issues –such as the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action– helped NGOs in pursuing women's agendas. Blackburn (2010) suggests that feminist NGOs began to form under the leadership of well-educated young women who pursued various aspects of women's rights. Her chapter highlights the importance of foreign funding for a number of Indonesian NGOs, reflecting the women's movement on the international stage. With the ratification of The CEDAW through Law Number 7 of 1984, various gender mainstreaming laws were passed. Throughout this article, we aim to unpack the role of NGOs in pursuing gender quotas in Indonesia.

Women's Parliamentary Representation in Indonesia

Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world, is often considered to have achieved a successful transition from authoritarian to democratic governance. Despite some limitations, this transition has been shaping and influencing the socio-political representation of women at both national and local levels. Indonesian women comprise half of the national population and were granted universal suffrage at the time of Independence, in 1945. Yet their presence in politics remains insignificant. Women's share in the national assembly (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/DPR) in the post-Suharto era has always been lower than 25 percent.

The struggle to improve women's role and status in Indonesia began long before the country's independence in 1945 (Prihatini 2019b). Along with men, Indonesian women also fought fiercely against colonial rule by the Netherlands and for the establishment of the modern Indonesian state (Oey-Gardiner and Bianpoen 2000). They also fought for the betterment of women's welfare by providing education for girls, refusing polygamy, and ending restrictions on women's active engagement in the public domain. Hence, the 1945 Constitution stipulates universal suffrage, which enabled women to vote and to stand in elections (Oey-Gardiner and Bianpoen 2000).

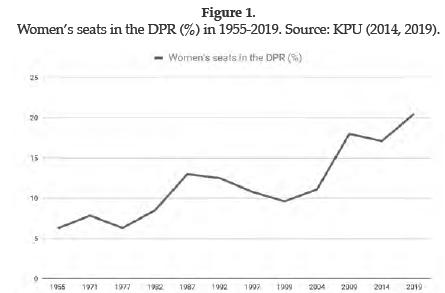

Like many other countries in the global South, women's parliamentary representation in Indonesia has been rather limited and irregular. In the first election in 1955, there were only 17 female MPs out of 272 elected lawmakers (6.25%). Progress was made during Suharto's authoritarian New Order regime (1966-1998) when in 1987 a peak of 13 percent was reached (see Figure 1). In the hope of improving this situation, a legislated gender quota of 30 percent for candidates in Indonesia was first implemented in the 2004 elections. Following this positive discrimination, women's share in the DPR rose significantly in 2009, with 18 percent of elected MPs being women. The next general election in 2014 showed a small setback as, instead of continuing the momentum of growth, the gender ratio was reduced slightly by one percentage point. The results in 2014 are considered as a paradox as the implementation of gender quotas was strengthened with the Electoral Commission's (Komisi Pemilihan Umum/KPU) regulation that imposed disqualification for parties who did not comply with 30 percent of candidates being women (Prihatini 2019a).

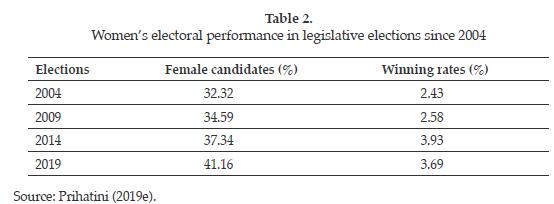

In the latest elections in 2019, parties promoted female candidates on an average of 41.2 percent, and women's share in the DPR reached a new record high at 20.5 percent (Perdana 2019). However, interestingly, women's winning rate (the number of women elected divided by the number of female candidates) was slightly reduced (see Table 2). And the fact that the winning rate for male candidates in the same year was 9.55 percent or 2.6 times higher than women begs the question as to why women's electability is so poor in Indonesia. Studies have shown that women's electoral performances in Indonesian elections continue to be influenced by an incumbency effect (Shair-Rosenfield 2012; Dettman, Pepinsky, and Pierskalla 2017), parties' nomination, including list position (Hillman 2017; Prihatini 2019a, 2019c), and cultural barriers (Simandjuntak 2012; Prihatini 2018a, 2019d).

As part of efforts to improve women's presence in parliament, gender quotas were advocated by activists, NGOs, and female lawmakers (Siregar 2010). Generally, quotas can be divided into three types: reserved seats, legislated (candidate) quotas, and voluntary party quotas (Norris 2004; Krook 2009; Bush 2011). The first type is the fixed number of seats set aside for women. The second type requires parties to nominate a certain percentage of candidates being women. These two modes are legal quotas which can be applied at the local or national level, and often are adopted in developing countries where equal access to political resources is limited for women (Chen 2010). Lastly, party quotas refer to internal party voluntary quotas such as applied by the People's Action Party (PAP) in Singapore (Tan 2016).

In order to re-examine the role of international NGOs in the implementation of gender quotas in Indonesia, this paper has located three key publications that are strongly relevant and comprehensive in explaining the dynamics surrounding legislation processes. The first is a book written by Ani Soetjipto (2005), a prominent women's rights advocate who is also an academic at the University of Indonesia (UI). Her compilation of essays provides a vivid account of women's political representation and the challenges in promoting gender quotas in the earlier years of Reformasi. The second (Siregar 2010) and third (Supriyanto 2013) books were both derived from PhD dissertations which investigate the political struggles related to the introduction of gender quotas. In addition to these materials, interview transcripts were also used to elaborate on the experiences of key actors involved.

International NGOs and Gender Quotas in Indonesia

Relationships between Indonesian women activists and their international counterparts started long before the country's independence and continue up to the present time. These networks can be traced back to as early as Kartini, who some consider to be Indonesia's first feminist. She developed a strong friendship with a Dutch activist, Stella Zeehandelaar (Ridjal, Margiyani, and Husein 1993). Kartini and Stella never met, but through their letters of correspondence, they shared their views on the importance of women having an education and being aware of social issues.

At the time of the authoritarian government under Suharto's presidency, it was difficult for Indonesian people, including women, to have the freedom to express their opinions and to be active in social and political organizations. But networks formed with overseas partners on international agreements, such as the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, helped them to run their programs.

Sadli's (2002) essay on the founding of the Women's Studies department at the University of Indonesia is a prime example of this. The Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada, assisted the Pusat Studi Wanita/PSW (Women's Studies Center) of the University of Indonesia to establish a Master degree program in Women's Studies back in 1990, particularly in designing its curriculum. Suharto's government opened more opportunities for women to become civil servants, whilst allowing state-run universities to establish Women's Studies Centers as a response to the Beijing Platform for Action (Davies 2005). These developments have become invaluable instruments for Indonesian women activists to pursue their agendas (Robinson 1998).

Support from international counterparts is also present in the Reformasi era, particularly in the phase of promoting democracy. International organizations, both government and non-government entities, have assisted Indonesia in the transition from an authoritarian to a democratic state (Siregar 2010). Numerous foreign observer units took part in the 1999 first free and fair general election, including the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the International Institute for Democratic and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), the International Republican Institute (IRI), the Carter Center, and the Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) (Teguh 2019). Soetjipto argues that back in the early Reformasi era, various issues became the focus of international NGOs, including free and fair elections, voters' education, electoral and capacity building for candidates for parliaments. And, thus, gender-sensitive program components were not present as the core interest of these organizations was solely to achieve peaceful, free and fair elections.

Soetjipto (2005) notes that in the 1999 election, women comprised merely 13 percent of candidates, only 4 out of 48 parties were led by a female (MKGR, PDI-P, PNI Soepeni, and PKNI), and women won 45 out of 500 seats (9%). The vast majority of parties in parliament (1999-2004) refused the notion of gender quotas (75%), and only 6.3 percent of parties –these were small and new parties– agreed that Indonesia required positive discrimination in the form of gender quotas in order to elect more women as lawmakers (Soetjipto 2005, 69). This condition was closely reflected in a survey conducted by CETRO in early 2000 which involved sitting parliamentarians. The study discovered 63.5 percent of lawmakers considered women's share in the current parliament as being far too low; however, 69.4 percent of respondents considered gender quotas as unnecessary (Soetjipto 2005, 35). The question then is who was among the first to promote gender quotas in Indonesia?

In his PhD thesis, which investigates the politics of women's movements in pursuing affirmative action policy in legislative elections in the post-Suharto era, Didik Supriyanto (2013) argues that the idea first formally emerged during the Indonesian Women's Congress (Kongres Perempuan Indonesia) held between 14-17 December 1998 in Yogyakarta (Supriyanto 2013, 33). The small number of women who became legislators (at national and local levels) forced female activists to revisit their political agenda. Thus, the congress mandated the Yogyakarta Declaration of 18 December 1998. The declaration emphasized that the Koalisi Perempuan Indonesia (KPI/Indonesian Women's Coalition for Justice and Democracy) should improve women's political awareness and increase women's participation as well as representation at all levels in decision-making processes to achieve gender parity.

In line with this mandate, Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, as the then KPI Secretary- General, announced the organization's political statement on 22 December 1998. One of the points raised was «demanding the opening of access to women's national leadership and the granting of a 50% quota in each of the legislative, executive and judicative institutions» (Supriyanto 2013, 106). Didik Supriyanto cites Katjasungkana, suggesting that the demand to improve women's political representation had already been discussed in the 5th Indonesian Women's Congress held in Bandung in July 1938. And yet, Indonesian leaders have ignored the reality in society of women encountering discrimination when it comes to power relations between men and women. Despite equal rights and universal suffrage being regulated in the 1945 Constitution, gender equality remains an unsolved problem in Indonesia (Prihatini 2019b). Various aspects are contributing to this development, including cultural and institutional barriers, which continue to hold women back from winning a seat in the DPR (Prihatini 2019a).

Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, a prominent women's rights activist who served as a legislator in 2004-2009, claims the initial advocacy for gender quotas in Indonesia was raised by KPI as it was indeed the mandate of the 1998 Indonesian Women's Congress held in Yogyakarta.

The idea certainly did not just come in an instant. Previously, I was the Convention Watch Advocacy Coordinator. Although the focus was on CEDAW socialization, especially in universities formed by the CEDAW Teaching Association (or Gender and Law), at that time we were having discussions with Nuri Suseno, a UI lecturer who resides in Sweden. She gave us so much information about affirmative action in Scandinavian countries. Then, in the KPI Congress, I expressed the need to review the Indonesian women's movement from Kartini up to 1928 and subsequent congresses, and found that in 1935 there was a struggle for the political rights of Indonesian women to be elected. Since then, several women have been elected members of the Volksraad and as mayors, especially in Bandung and surrounding areas. (Katjasungkana, personal interview 2 July 2, 2019)

Similar narratives were given by Dian Kartikasari, the current Secretary- General of KPI. She explains that at an early stage of the advocacy for gender quotas in Indonesia no international NGO was directly involved. The 30 percent quota has been proposed by the KPI since 1999, taking into account the potential and opportunities for political support for women in parliament. The 30 percent was considered a safe minimum threshold for political influence that women could achieve.

International NGOs, such as The Asia Foundation (TAF), did not have a special fund allocation to support the issue of quotas. It was all a joint venture between KPI and NGOs. When conducting seminars at LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Sciences), for example, TAF contributed in paying consumption, the CIDA (Canadian International Development Agency) paid the honorarium for speakers, the KPI provided printed materials, and the PDPol (Pusat Pemberdayaan Perempuan dalam Politik Indonesia/Center for Women in Politics) bought the banners. That was in 1999-2002. (Kartikasari, personal interview, July 3, 2019)

She further suggests that from 2003 onwards, The Asia Foundation (TAF), CETRO (Center of Electoral Reform/Pusat Reformasi Pemilu), Kemitraan (Partnerships) –an NGO sponsored by various bilateral/multilateral donor agencies and private sectors– and other organizations, such as the Balcony Faction (Fraksi Balkon), started to support the campaign for gender quotas. The latter refers to women's rights activists who attended the plenary session to enact the Law on

Elections in the national parliament on 18 February 2003 (Siregar 2010). They sat in the balcony of the session room, waiting patiently until the end to find out whether the words «30 per cent quota for women» would be mentioned. The legislators in the parliament called these activists the «Fraksi Balkon» (Balcony Faction), implying that they had a role like one of the parliamentary factions who participated in enacting the Election Law, in which the quota for women was instituted. Kartikasari asserts that initially very few international NGOs were keen on supporting the campaign for gender quotas in Indonesia, including activities such as «1,000 Umbrellas» and the «Vote for Women» pin.

During the hearings for the draft of the Electoral Bill in 2003, there were only TAF, Kemitraan, CETRO, and electoral monitoring groups like Ansipol (Aliansi Masyarakat Sipil untuk Perempuan & Politik/Civil Society Alliance for Women & Politics), JAMPPI (Jaringan Masyarakat Pemantau Pemilu Indonesia/Indonesian Election Monitoring Community Network), and JPPR (Jaringan Pendidikan Pemilih Untuk Rakyat/People's Voter Education Network) involved. Hence, during the revision of the Electoral Law in 2008, more NGOs participated in the process. (Kartikasari, personal interview, July 3, 2019)

Another key activist in the advocacy of gender quotas in Indonesia is Ani Soetjipto of the University of Indonesia (UI). Soetjipto has been promoting gender equality through her academic career and social activism. As one of the founders of CETRO, she argues CETRO and other NGOs worked together with KPI to increase women's parliamentary representation.

There are at least four factors that influenced their strong intention to support the campaign for gender quotas as an institutional tool to elect more women to parliament. The first was the encouragement from President Habibie, who suggested that Indonesia needed to hold free and fair elections in order to elect legitimate leaders. And thus, various International NGOs came to Indonesia to provide assistance in establishing democratic elections. Some NGOs have a gender dimension, and part of this is ensuring better representation of women as political leaders. The second factor was that with a newly elected democratic government, Indonesia offers more space for women to be active in politics. The third aspect relates to the nature of Reformasi. Suharto's government strengthened the domestication of women. With Reformasi, we want women to go into the public sphere. Lastly, after being too long disconnected from politics, we cannot use ordinary or incremental ways to ask women to enter politics. We needed quotas. Even though at that time we were still not sure what kind of quota we wanted to use. (Soetjipto, personal interview, July 11, 2019)

Soetjipto further rejects the idea that the struggle for a quota is only an imitation of foreign ideas, particularly those of Western feminists. When questioned on this, she responded strongly:

No, I don't think so. At that time, we did not have any experience with quotas. Friends from International NGOs helped us to understand what they are. Some of them, for instance, shared with us the experience of the Philippines and other countries in the implementation of gender quotas. We then decided which type of quota would be suitable for us in Indonesia. (Soetjipto, personal interview, July 11, 2019)

Her statement reflects the common position that although support from women activists from other countries and International organizations is important in their struggle, Indonesian women activists try to find their own strategies that match the Indonesian situation.

The proposal for quotas for women was fiercely challenged by both male and female politicians. One monumental rejection came from the country's first female president, Megawati Sukarnoputri. She stated that a quota would only show illusory progress on the part of women (Siregar 2010). In her perception, implementation of a quota would weaken institutions such as the parliament. She even stated that «enacting the quota means creating new discrimination against men» (Swara Androgini 2003, 11).

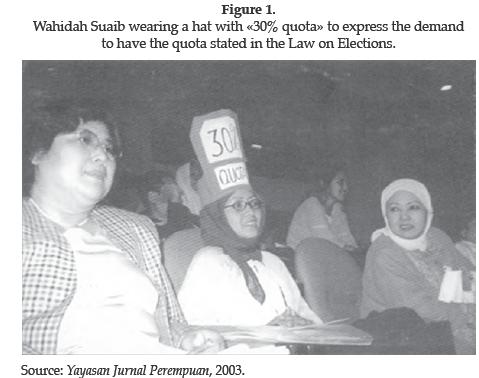

Reflecting on her personal experience during the hearings of the Electoral Law draft in 2003, Wahidah Suaib of Kemitraan explains that the NGO supported the advocacy for gender quotas in 2002-2003 by establishing a working group dedicated to ensure better political representation for women in politics. In Figure 2, Suaib takes part in the Fraksi Balkon, listening to the hearings in the DPR. Activists like Yuda Irlang, Masruchah, Nia Sjarifuddin, Eko Subiantoro, Smita Notosusanto, Sri Wardani, and Ery Seda continued the campaign in 2006-2008.

For the advocacy in 2002-2003, I think it is best to consult with KPI as the crux of the movement since 1999. Chusnul Mar'iyah (an academic at the University of Indonesia) and Nursyahbani Katjasungkana both represent KPI. CETRO as the center, or some sort of base camp, for NGOs promoting electoral reforms is also a key player, hence Ani Soetjipto, Ery Seda, and Sri Budi Eko Wardani should be excellent in outlining the campaign for gender quotas. (Suaib, personal interview, July 3, 2019)

Ani Soetjipto claims there were four main international NGOs that helped women activists in promoting gender quotas in Indonesia, especially after the 2004 elections, when a quota of 30 percent female candidates was implemented. These NGOs are IFES (The International Foundation for Electoral Systems), the NDI (the National Democratic Institute), International IDEA, and the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). IRI was also involved but not so much, as the US at that time was dominated by the Democrats.

The international NGOs with a women's division, such as International IDEA, helped by explaining multiple types of quota models and giving examples of countries implementing them. They let Indonesian activists choose the model suitable for Indonesia in the hope of increasing women's representation. The main forms of their help were funding and technical assistance. (Soetjipto, personal interview, July 11, 2019)

Delima Saragih, IRI's Regional Program Manager, echoes this information as she describes programs which are in line with the campaign for increasing women's political representation in Indonesia. These include last year's training for women who are running for office in four provinces. «We also did training for female candidates towards the 2009 and 2014 elections. The 2004 and 2009 elections were mixed training, including for both male and female candidates,» said Saragih. She asserts that supporting gender quotas was part of the bigger electoral reform campaign and transition to democracy programs. Similarly, Nursyahbani Katjasungkana highlights the fact that the provision of gender quotas was not a foreign concept that was imposed on the Indonesian political institutional system.

Remaining Challenges

Gender norms' diffusion in the form of the implementation of gender quotas in Indonesia has displayed one of the best examples of how women's rights activists are pursuing their agendas in improving women's political representation. Ery Seda of the University of Indonesia argues that the affirmative action policy in the form of legislated gender quotas was organized and fully supported by networks of NGOs, political parties, the Women's National Commission (Komisi Nasional Perempuan), and parliamentary bodies like the Parliamentary Women's Caucus (Kaukus Perempuan Parlemen) and the Indonesian Women's Political Caucus (Kaukus Politik Perempuan Indonesia).

The role of international NGOs or donors here was to strengthen the institutional capacity of these networks. Meanwhile, the diffusion of norms or values on gender equality from the global North did only occur in Indonesia to some extent through the gender quotas policy. This is partly due to the considerable resistance to the values of gender equality, both in the form of ideas and counter-movements. For example, conservative parties are misusing religious values to counter any form of gender equality campaigns. (Seda, personal interview, July 10, 2019)

Ery Seda's assertions provide a clear idea as to what challenges remain in Indonesia today when it comes to the promotion of gender equality in the country. The legislated 30 percent gender quotas policy was considered to be an important milestone in women's representation in Indonesian politics. This part-success story was possible because the momentum to create such a reform was made available at the start of Reformasi in 1998. This key factor enabled the Electoral Law and the Political Parties Law to be reformed. And with strong advocacy by networks of NGOs, affirmative action was finally introduced in Indonesia.

Seda claims that today the quota policy has been relatively successful in increasing women's share in the Indonesian parliament. But this growth is solely a descriptive or numeric representation and not yet a quality substantive representation of female MPs in the DPR. Various factors contribute to the limitations of this achievement, including loopholes in the implementation of gender quotas, the lack of caderization by political parties, and the practices of a political dynasty that is so rampant that it only strengthens the political oligarchy.

Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated that the relationships between Indonesian women activists and their international counterparts have been very fruitful in promoting women's political representation. These networks have helped women to introduce the provision of gender quotas in Indonesia, despite political rejections on numerous occasions throughout legislation processes.

The current paper also identifies the key participants behind the campaign for a 30 percent gender quota for legislative candidates. The findings suggest that only a limited number of international NGOs –sponsored by the global North, including the US, Australia, and Canada– took part in the initial stages of the campaign before 2004. More support was given following the 2004 elections, and the vast majority of this assistance was in the form of strengthening the institutional capacity of local NGOs and women activists' networks. This experience suggests the nexus of gender and international relations is a growing field in which the global North continues to influence the process of improving women's political representation in countries in the global South. This network is an excellent showcase of how women activists' networks can be an excellent medium to grow support to achieve higher political status for women.

We found that the influence of international NGOs has been significant and yet indirect. We also found that the affirmative action policy was only part of bigger projects that promote gender equality and a transition to democracy. Also, as women's share in parliament has been limited and has fluctuated, it is apposite to suggest that remaining challenges persist in increasing women's success rate. We argue that while quotas do not solve gender disparity in Indonesia and in many other Asian parliaments (Prihatini 2018b), the collaboration between local and international NGOs should be extended to improve women's electoral performance by maximizing the strategies relevant to increasing electability. Various training programs on how to present women as aspiring candidates are greatly needed.

References

Bessell, S. 2010. «Increasing the Proportion of Women in the National Parliament: Opportunities, Barriers and Challenges». In Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Institutions and Society, edited by Edward Aspinall and Marcus Mietzner, 219-42. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [ Links ]

Blackburn, Susan. 2010. «Feminism and the Women's Movement in the World's Largest Islamic Nation». In Women's Movements in Asia, edited by Mina Roces and Louise Edwards, 21-33. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bush, Sarah. 2011. «International Politics and the Spread of Quotas for Women in Legislatures ». International Organization 65 (1): 103-137. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000287. [ Links ]

Byers, Alton C. 2007. «NGO Service Delivery and Promotion of Democracy: Two TMI Initiatives in Nepal and Peru». Mountain Research and Development 27 (2): 180-181. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.0910. [ Links ]

Chen, Li-Ju. 2010. «Do Gender Quotas Influence Women's Representation and Policies?» The European Journal of Comparative Economics 7 (1): 13-60. DOI: http://eaces.liuc.it/18242979201001/182429792010070102.pdf. [ Links ]

Cumming, Gordon D. 2011. «Good Intentions Are Not Enough: French NGO Efforts at Democracy Building in Cameroon.» Development in Practice 21 (2): 218-231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2011.543275. [ Links ]

Davies, Sharyn G. 2005. «Women in Politics in Indonesia in the Decade Post-Beijing.» International Social Science Journal 57 (184): 231-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2005.00547.x. [ Links ]

Dettman, Sebastian, Thomas B. Pepinsky, and Jan H. Pierskalla. 2017. «Incumbency Advantage and Candidate Characteristics in Open-List Proportional Representation Systems: Evidence from Indonesia». Electoral Studies 48 (August): 111-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.06.002. [ Links ]

Herrold, Catherine E. 2016. «NGO Policy in Pre- and Post-Mubarak Egypt: Effects on NGOs' Roles in Democracy Promotion». Nonprofit Policy Forum 7 (2): 189-212. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2014-0034. [ Links ]

Hillman, Ben. 2017. «The Limits of Gender Quotas: Women's Parliamentary Representation in Indonesia». Journal of Contemporary Asia, August, 1-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1368092. [ Links ]

Jacka, Tamara. 2010. «Women's Activism, Overseas Funded Participatory Development, and Governance: A Case Study from China». Women's Studies International Forum 33 (2): 99-112. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2009.11.002. [ Links ]

KPU. 2014. «Buku Data Dan Infografik Pemilu Anggota DPR RI & DPD RI 2014 [Book of Data and Infographic General Election of DPR RI & DPD RI 2014]». Komisi Pemilihan Umum/KPU [General Elections Commission]. [ Links ]

KPU. 2019. «Hasil Pemilu 2019 [2019 Elections Results]» Komisi Pemilihan Umum/KPU [General Elections Commission]. September 2, 2019. https://www.kpu.go.id/index.php/pages/detail/2019/1099. [ Links ]

Krook, Mona Lena. 2009. Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Norris, Pippa. 2004. «Women's Representation». In Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior, 179-208. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Oey-Gardiner, Mayling, and Carla Bianpoen, eds. 2000. Indonesian Women: The Journey Continues. Canberra: RSPAS Publishing, ANU. [ Links ]

Perdana, Aditya. 2019. «Analisa Perolehan Kursi Pemilu DPR Dan DPD RI Tahun 2019: Kekerabatan Dan Klientalisme Dan Keterwakilan Politik [Analysis of the Seats in the DPR and DPD RI Election in 2019: Kinship and Clientelism and Political Representation] ». Puskapol FISIP UI. May 26, 2019. https://www.puskapol.ui.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Rilis-Media-Analisa-Perolehan-Kursi-Pemilu-2019.pdf. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2018a. «Indonesian Young Voters: Political Knowledge and Electing Women into Parliament.» Women's Studies International Forum 70 (September): 46-52. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.07.015. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2018b. «Women's Representation in Asian Parliaments: A QCA Approach.» Contemporary Politics 25 (2): 213-235. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2018.15 20057. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2019a. «Women Who Win in Indonesia: The Impact of Age, Experience, and List Position». Women's Studies International Forum 72 (January): 40-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.10.003. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2019b. «Political Parties and Participation: Indonesia». In Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures, edited by Suad Joseph. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2019c. «Islam, Parties, and Women's Political Nomination in Indonesia». Politics & Gender, 1-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000321. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2019d. «Women's Views and Experiences of Accessing National Parliament: Evidence from Indonesia». Women's Studies International Forum 74 (May): 84-90. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.03.001. [ Links ]

Prihatini, Ella S. 2019e. «Electoral (in)equity.» Inside Indonesia, March 8, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.insideindonesia.org/electoral-in-equity. [ Links ]

Rahman, Sabeel. 2006. «Development, Democracy and the NGO Sector: Theory and Evidence from Bangladesh». Journal of Developing Societies 22 (4): 451-473. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X06072650. [ Links ]

Ridjal, Fauzie, Lusi Margiyani, and Agus Fahri Husein, eds. 1993. Dinamika Gerakan Perempuan Di Indonesia [The Dynamics of the Women's Movement in Indonesia]. Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana. [ Links ]

Roces, Mina. 2010. «Asian Feminisms: Women's Movements from the Asian Perspective.» In Women's Movements in Asia: Feminism and Transnational Activism, edited by Mina Roces and Louise P. Edwards, 1-20. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Robinson, Kathryn. 1998. «Indonesian Women's Rights, International Feminism and Democratic Change». Communal/Plural 6 (2): 205-23. [ Links ]

Sadli, Saparinah. 2002. «Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context». In Women in Indonesia: Gender, Equity and Development, edited by Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, 80-91. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [ Links ]

Shair-Rosenfield, Sarah. 2012. «The Alternative Incumbency Effect: Electing Women Legislators in Indonesia.» Electoral Studies 31 (3): 576-87. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.05.002. [ Links ]

Simandjuntak, D. 2012. «Gifts and Promises: Patronage Democracy in a Decentralised Indonesia ». European Journal of East Asian Studies 11 (1): 99-126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700615-20120008. [ Links ]

Siregar, Wahidah. 2005. «Parliamentary Representation of Women in Indonesia: The Struggle for a Quota.» Asian Journal of Women's Studies 11 (3): 36-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2005.11665993. [ Links ]

Siregar, Wahidah. 2010. Gaining Representation in Parliament: A Study of the Struggle of Indonesian Women to Increase Their Numbers in Parliaments in the 2004 Elections. Saarbrucken: LAP Lambert. [ Links ]

Soetjipto, Ani Widyani. 2005. Politik Perempuan Bukan Gerhana [Women Politicians Are Not Eclipsed]. Jakarta: Kompas. [ Links ]

Suleiman, Lina. 2013. «The NGOs and the Grand Illusions of Development and Democracy ». Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 24 (1): 241-261. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9337-2. [ Links ]

Supriyanto, Didik. 2013. Politik Perempuan Pasca-Orde Baru [Women's Politics in Post-New Order]. Jakarta: Rumah Pemilu. [ Links ]

Swara Androgini. 2003. «Advokasi Jaminan Keterwakilan Perempuan Dalam Undang-Undang Politik [Advocacy to Guarantee Women's Representation in the Law of Political Party]». Swara Androgini II (5): 10-18. [ Links ]

Tan, Netina. 2016. «Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives». Pacific Affairs 89 (2): 369-393. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5509/2016892369. [ Links ]

Teguh, Irfan. 2019. «Sejarah Pemantau Asing Di Indonesia: Bermula Pada Pemilu 1999 [History of Foreign Observers in Indonesia: Starting in the 1999 Election]». Tirto. Tirto.id. March 27, 2019. Retrieved from https://tirto.id/sejarah-pemantau-asing-di-indonesia-bermula-pada-pemilu-1999-dkmU. [ Links ]

*Ella Syafputri Prihatini

Postal address: 35 Stirling Hwy, Nedlands, 6009 Perth, Australia.

Email address: ella2syafputri@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6710-1250

Recently graduated from UWA with PhD thesis which investigates women's parliamentary representation in Indonesia. Her research interests focus on women's political participation, gender studies of Asia, and electoral politics in Indonesia.

**Wahidah Zein Br Siregar

Postal address: Jalan A. Yani 117, Surabaya, 60237 Jawa Timur, Indonesia.

Email address: adek.azsiregar.siregar@gmail.com

Vice Chancellor for Academic and Institutional Affairs at UIN Sunan Ampel (UINSA) Surabaya, Indonesia. Published in Asian Journal of Women's Studies about women's political representation in Indonesia.

Article received on the 18th of July and accepted for publication on the 14th of November 2019.