Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.13 no.1 Lisboa 2012

Psychological approach to endrometriosis: Women´s pain experience and quality of life improvement

Abordagem psicológica na endometriose: Experiência de dor e melhora na qualidade de vida das mulheres

Natália Mendes & Bárbara Figueiredo

Escola de Psicologia da Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Contato:mnmendes@med.up.pt

ABSTRACT

Endometriosis is a chronic condition affecting 10 to15% of women in childbearing age. Understanding the impact of this disease on women’s well-being is still a challenge, namely to intervene. Pain is the most current and troublesome symptom. Although medical treatments for pain relief are effective, recurrence rate remains significant, calling for a better understanding and development of new approaches for pain management. A group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for management of associated co-morbidities is suggested, paying special attention to Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP). CBT design can be grounded on information collected from focus groups and a one-group exploratory trial. Evaluation of therapy effectiveness is possible to be performed by comparing group CBT to Usual Care (UC) and Support Group (SG) in a randomized controlled trial. Research in this area could represent an important step in providing a solution to the management of endometriosis and, to the best of our knowledge, the first national psychological approach for its understanding and treatment.

Keywords- endometriosis, women’s experience, chronic pelvic pain, cognitive behavioral therapy

RESUMO

A endometriose é uma doença crónica que afecta 10 a 15% das mulheres em idade reprodutiva. O entendimento do impacto da doença no bem-estar estar das mulheres continua a ser um desafio, nomeadamente para a intervenção. A dor é o sintoma mais frequente e preocupante. Apesar dos tratamentos para alívio da dor serem eficazes, a taxa de recorrência é significativa, apelando à necessidade de melhor conhecer a doença e desenvolver novas abordagens para gestão da dor que lhe está associada. Sugere-se uma terapia Cognitivo Comportamental (CBT) de grupo para gestão das comorbilidades associadas, com especial foco na Dor Pélvica Crónica (CPP). O design da CBT baseia-se em informação recolhida de focus groups e um ensaio exploratório de um grupo. A avaliação da CBT será realizada através de um ensaio clínico randomizado, comparando a terapia com o Tratamento Usual (UC) e Grupo de Apoio (SG). A investigação nesta área poderá representar um passo importante no desenvolvimento de uma solução para gestão da endometriose, e de acordo com o nosso entendimento, a primeira abordagem psicológica nacional para o seu estudo e tratamento.

Palavras-chave- endometriose, experiência das mulheres, dor pélvica crónica, terapia cognitivo comportamental

Endometriosis is a progressive, chronic, gynecological condition in which endometrial tissue grows outside of the uterine cavity, resulting in inflammation. Endometrial tissue responds to hormonal alterations and bleeds during menstrual cycles (National Endometriosis Society (NES), 2007) leading to the development of cysts, fibroses and adhesions, that may result in chronic pelvic pain (CPP) and infertility (Mao & Anastasi, 2010). Ten to 15% of women in childbearing age are affected (Kaatz, Solari-twadell, Cameron, & Schultz, 2010). However, it has been also found in pre-menarcheal girls without an obstructive anomaly of the reproductive tract (Marsh & Laufer, 2005). Although the disease is commonly understood as a women’s health condition there are two reports suggesting its occurrence in men (Fukunaga, 2011; Pinkert, Catlow, & Straus, 1979). Endometriosis is frequently described as a clinical enigma as there is no established etiology; theories remain speculative and range from congenitally acquired or genetic predispositions to alterations in the endocrine system (Buck Loius et al., 2011).

Diagnose

Diagnose involves significant delay: 11.7 years in the U.S., 8 years in the U.K. (Hadfield, Mardon, Barlow, & Kennedy, 1996) and 7.6 years in Norway (Husby, Haugen, & Moen, 2003). In a qualitative study of women’s experiences reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis, delay between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis was explained by two factors: (1) individual - women’s inability to differentiate between "normal" and "abnormal" menstrual experiences; embarrassment to communicate symptoms; and perceiving themselves as the unlucky ones that have painful menstrual cycles; (2) medical – pain normalized by family doctors and disbelief surrounding genuineness or severity of women’s symptoms; intermittent hormonal suppression of symptoms due to medical prescription of oral contraceptive pill; and use of nondiscriminatory investigations (Ballard, Lowton, & Wright, 2006). Failure to identify a noninvasive tool or serum marker has also been reported as a diagnosis delayer, as clinical examination procedures (laparoscopy) are invasive and require specialized medical resources (Banerjee, Mallikarjunaiah, & Murphy, 2010). Delay generates distress (Ballard, Lowton, & Wrigt, 2006; Lorençatto, Petta, Navarro, Bahamondes, & Matos, 2006) and is greater for women reporting CPP.

Current medical treatments

Current treatment options include hormonal therapies: gonodatropin-releasing hormone – (GnRH) analogues, progesterone, and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are the most common drugs used for pain relief (Gambone et al., 2002). Surgery (laparoscopy, hysterectomy) is reserved for problematic cases. (Banerjee, Mallikarjunaiah, & Murphy, 2010). Although these treatments show efficacy for pain relief, recurrence rate remains significant (Ozawa et al., 2006). Forty four percent of women experience recurrence of symptoms within one year after surgery (Lapp, 2000) and there is insufficient evidence on the long-term effects of pharmacologic treatments (Ozawa, 2006). Management of endometriosis associated pain has not yet been satisfied and new approaches are needed, especially because it significantly affects women’s quality of life (Denny & Khan, 2006; Kumar, Gupta, & Maurya, 2010; Sepulcri & Amaral, 2009).

Symptoms and impact on quality of life

Almost 50% of women with endometriosis have CPP (Pugsley & Ballard, 2007). Severity of pain is not directly correlated to the extent of endometrial tissue found (Evers, 1994) and it appears that pain has taken a back seat to fertility, as medically and socially the disease is primarily conceptualized as an infertility problem (Nunnink & Meana, 2007). Nevertheless, pain is still the most current and troublesome symptom (Gerlinger, Schumacher, Faustman, Colligs, Schmitz, & Seitz, 2010) and women present it to their gynaecologists three times more often than fertility (Carpan, 1996).

There are several studies reporting impact on physical, mental and social well-being. On a prospective study assessing depressive symptoms, anxiety and quality of life in women with pelvic endometriosis, 86.5% presented depressive symptoms (mild in 22.1%, moderate in 31.7%, and severe in 32.7%). A positive correlation between current pain intensity and anxiety was also reported (Sepulcri & Amaral, 2009). Depression was found to be highly prevalent in endometriosis’ patients with and without CPP, but higher on women with CPP, resulting in complaints like somatic concerns, work inhibition, and sadness (Lorençatto, Petta, Navarro, Bahamondes, & Matos, 2006). On the other hand, chronic pelvic pain patients, with or without endometriosis, were found to be depressed, highly alienated, and exhibited impaired quality of life: social withdrawal, fatigue, lack of interest in their work, decreased sex desire, negative self image, pessimistic attitude and worthlessness (Kumar, Gupta, & Maurya, 2010). Anger, grief and despair are also associated with the experience of living with endometriosis, particularly when women’s fertility is impaired (Kaatz, Solari-twadell, Cameron, & Schultz, 2010). A qualitative study exploring experiences of women with the disease, found several dimensions of their lives to be affected: work, family, social activities, finances, sexuality and intimacy; both sexual and intimate relationships showed compromise due to dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and decreased libido (Huntington & Gilmour, 2005).

New perspectives on endometriosis treatment

Concerning that all dimensions of women’s lives are affected, some studies report the need to provide multi-disciplinary healthcare in view of the physical, social and emotional manifestations of the disease (D'Hooghe & Hummelshoj, 2006; Kumar, Gupta, & Maurya, 2010; Lorençatto, Vieira, Marques, Benetti-Pinto, & Petta, 2007; Sepulcri & Amaral, 2009). CBT improves physical and mental functioning (Kumar, Gupta, & Maurya, 2010;Morley, Eccleston, & Williams, 1999). Areas to address in intervention programs should include development of coping strategies, in order to stop catastrophization - a predictor of persistent pain (Martin et al. 2011), anxiety and stress decrease, and mental and physical functioning improvement, thus breaking the cycle of inflammation, sickness behaviour and depression (Siedentopf, Triverdian, Rucke, Kentenich, & Arck, 2008). There are reports of implementation of these treatments in some countries (Kames, Rapkin, Naliboff, Afifi, & Ferrer-Brechner, 1990; Mao & Anastasi, 2010; Metzger, 1997; Morley, Eccleston, & Williams, 1999), however, to the best of our knowledge, none in Portugal. Therefore, developing a psychological approach to endometriosis management represents an important therapeutic tool, especially for women undergoing several surgical/pharmacological treatments and experiencing recurrence of symptoms. It may also decrease depressive symptoms that result from hormonal therapy (Lorençatto, Petta, Navarro, Bahamondes, & Matos, 2006), and potentiate women’s expertise on managing the disease.

Finally, understanding the impact of endometriosis on the physical, mental and social well-being of women is still a challenge. There are several quantitative studies describing symptoms however, little qualitative research has been conducted (Ballard, Lowton, & Wrigt, 2006; Cox, Henderson, Andersen, Cagliarini, & Ski, 2003; Gylmour, Huntington, & Wilson, 2008). Specifically one focusing on women’s pain experience - and much of what exists lacks rigour in key areas (Denny & Khan, 2006). Perhaps giving women a voice in describing their own interpretation of symptoms and experiences may help understand the impact of the disease, providing essential knowledge for the development of key areas to address in future interventions.

To improve quality of life of women living with endometriosis, a CBT based on their reports of the disease, giving special attention to the experience of pain is considered the most appropriate approach. This constitutes an important piece to the contribution of a holistic solution to the management of endometriosis, particularly in the Portuguese context.

A better understanding of the disease as well as the design and evaluation of an interventional program are the main goals. Developing an interventional approach for endometriosis symptoms giving special attention to CPP, based on CBT principles will enable:

1. Description and analysis of chronic pelvic pain experience of endometriosis;

2. Development and implementation of a one-group exploratory trial CBT aiming at: a) CPP management and co-morbidities associated; b) improvement of health related quality of life in two dimensions: i) physical health - reduce pain level, increase physical activity level, stop chronic fatigue cycle, improve sleep quality; ii) mental health - reduce anxiety level, reduce depression symptoms, promote management and adaptation to disease, facilitate social integration. CBT can accomplish better outcomes if being implemented in an outpatient context. Outcome of this analysis will offer further information about CBT consistence with women’s treatment preferences. If necessary, contents and sessions will be redesigned for the randomized controlled trial;

3. Conductance and evaluation of the effectiveness of group CBT by comparing CBT to Usual Care (UC) and Support Group (SG) in a controlled clinical trial, with several outcome measures and post-treatment and 6 months follow-up.

METHOD

A qualitative approach can be use to assess women’s experience of living with the disease, by conducting focus groups. This method of collecting data has advantages in comparison with objective measures as providing women the opportunity to use their own words to express themselves. Also, group interaction may help women explore and clarify their view in ways that would be less accessible within an interview (Kitzinger, 1995). By elaborating previously a topic guide containing main themes for discussion, information gathered could be more accurate and aligned with objectives. Therefore, we suggest this should be developed based on literature review and discussion within a multi-disciplinary team constituted by an anesthesiologist specializing in pain, a gynecologist, a psychologist and a sociologist experienced in leading focus groups. During sessions, women should be encouraged to discuss freely several aspects of their disease accordingly to the topic guide. Data analysis: content thematic analysis methodology (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) may be applied to data in order to map emergent themes. To calculate inter observer agreement, analysis should be performed independently by two researchers. In case of disagreement a third rater can be consulted.

CBT development: content of sessions and main areas to address may emerge from thorough literature review, the focus groups and the exploratory trial. A one-group exploratory trial will be carried out before the controlled clinical trial because it may enable preliminary results that can help improve the treatment administration (Klinkhammer-Schalke et al., 2008). After sessions women will give their opinion about treatment and alterations can be carried out if necessary.

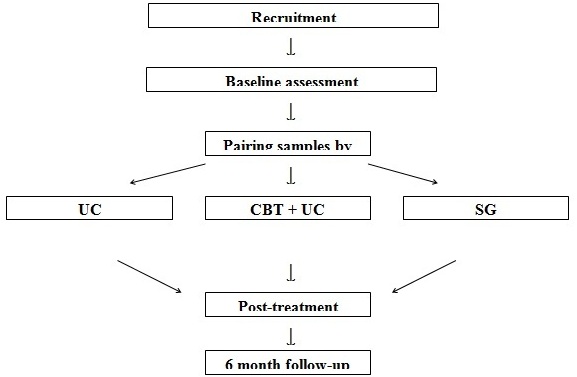

A quantitative approach is necessary to test CBT’s efficacy with Randomized Controlled Trials being considered the gold-standard in terms of research evidence (Atkins, 2009). A controlled clinical trial (Fig. 1) can be conducted with baseline and post-treatment assessments, and 6 month follow-up. Sample may be paired accordingly to the following criteria: age, educational status, professional status, socio-demographic status, parity, and stage of the disease. Group size and composition is advised be limited between 6 to 8 participants. An appropriate number to facilitate group interaction, while enabling enough time for each group member to speak and share experiences (The American Group Psychotherapy Association [AGPA], 2007).

Figure 1

Description of overall clinical trial design

In order to verify outcomes differences introduced by the therapy program, participants should be distributed to one of the following experimental groups: a) group CBT plus UC, b) UC only, and SG only. Data analysis: all analysis may be conducted using an intention to treat principle. This analytical principle allows analyses of impact based on comparable groups of subjects across the intervention condition (Brown et al., 2008). Data should be analyzed to assess changes in mean-scores at pre (baseline) and post-treatment and, post-treatment to follow-ups. Trial must be performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Group CBT Intervention

Cognitive-behavioral principles are broadly used in pain management programs (PMP) (McCracken & Turk, 2002; Dysvik, Vinsnes, & Eikeland, 2004; Zarnegar & Daniel, 2005; Thorn & Kuhajda, 2006; Turk, Wilson, & Cahana, 2011) resulting in daily functioning improvement (McCracken & Turk, 2002), coping skills and health-related quality of life enhancement (Dysvik, Vinsnes, & Eikeland, 2004). Common contents and techniques derive from operant conditioning and CBT (Turk & Cahana, 2011): reconceptualisation of the patient’s pain from uncontrollable to manageable; promotion of feelings of self-efficacy and self-control; education and training of relaxation techniques and problem solving strategies; promotion of an active role in treatment as well as patient’s responsibility; and individualization of treatment goals to each patient needs. As recommended by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP, 2005) main areas to address should be activity and pacing, stress management, relaxation training, assertive communication, sleep, intimate and sexual relationships, family, relapse prevention, and work rehabilitation.

Considering almost 50% of women with endometriosis have CPP (Pugsley & Ballard, 2007) and that not all of them suffer from infertility problems or are trying to get pregnant, it is imperative to address psychological treatments for endometriosis in a perspective beyond fertility and gynecological issues. Therefore, a chronic pain lens approach to the disease is suggested. PMP principles are the cornerstone in the development of the proposed CBT; the program considers Turk and Okifuji’s (1999) cognitive-behavioral principles to pain management. Techniques and contents apply to endometriosis themes, attributing a specific language to the therapy program.

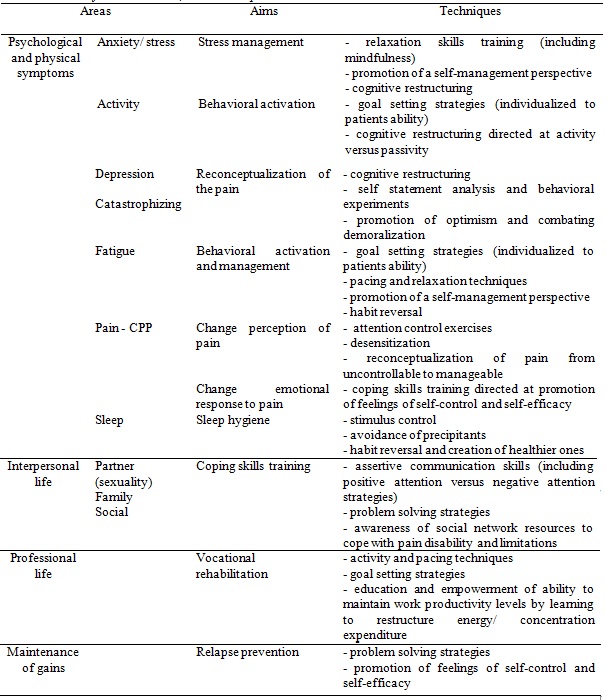

Therapy contents: several clinical contents are listed below with a description of their pertinence for inclusion in the therapy. For an overview of CBT program please consider Table 1.

Table 1 - CBT Contents by Area and Aims, and Techniques

a) Activity and fatigue - chronic pain patients enter a chronic cycle where fear of injury and pain leads them to passivity; when activity outweighs their usual daily levels, pain increases carrying women to passivity, leading to a vicious chronic pain-fatigue cycle. This highlights the need to stop the vicious cycle of fatigue and introduce physical and exercise rehabilitation to the program.

b) Anxiety/ stress – according to the stress-appraisal-coping model of pain (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) patients’ cognitions predict their adjustment to pain. Mediating variables to adjustment are: appraisal of the pain and stressors, beliefs about their ability to exert control over pain, and their choice of coping strategies (Thorn, 2004). Several techniques aiming at stress management and cognitive appraisal can be considered along therapy sessions.

c) Depression - depressive symptoms are common in women with endometriosis, affecting 86% of women with pain and 38% of women without pain (Lorençatto, Petta, Navarro, Bahamondes, & Matos, 2006). Typical pain-related cognitive mechanisms associated with depression, like catastrophizing, are robust predictors of disability and pain severity (Martin, Johnson, Wechter, Leserman, & Zolnoun, 2011). Catastrophization has been defined as a negative cognitive and emotional coping response to pain, that leads to amplification of pain symptoms and feelings of helplessness and pessimism (Sullivan et al., 2001). To avoid cognitive negative mechanisms, the Cognitive Model of Pain can be presented and worked during CBT.

d) Relationships – women with endometrisosis experience interrelation limitations due to pain itself or pain-related disabilities, which may result in a sensation of isolation. Relationships with family members and partner may be compromised, and sexuality may be impaired due to dyspareunia. Pain impact on family and social dimension of women’s lives is considered along therapy sessions. This fact led authors to choose a group format therapy because of the added dimension of the group process – interaction among group members.

e) Vocational dimension – Fourquet, Báez, Figueroa, Iriarte and Flores (2011) found work productivity to be at high risk in women with the disease: 7.41 hours of work time per week are lost when symptoms are worse; they also concluded a high impact on work-related domains: 13% absenteeism, 65% of work impaired (presenteeism), 64% loss in work productivity, and 60% of activity impairment. Realizing the importance of a rehabilitative component, and the necessity to maintain an active professional life, work rehabilitation should be considered.

f) Pain – in current PMPs pain is indirectly addressed by focusing therapy techniques on the implications pain introduce to life dimensions (previously mentioned in items a, b, c, d and e). In that sense, pain level and limitations may decrease by introducing behavioral and cognitive changes that are reinforcing pain behaviors and beliefs.

Usual care

This treatment condition represents a control arm in the trial and includes women who are attended in the National Health Care System, and are assisted in accordance with the National Plan for Pain Management (Nº:11/DSCS/DPCD, 18/06/08).

Support group

SG also represents a control arm, differing from UC because participants engaging in this type of group have the opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other women with the disease, in a supported environment. Sessions can be mediated by a psychologist. No therapeutic techniques will be applied to assure outcomes from the experimental group are due to the therapeutic techniques alone avoiding contaminating the ability to isolate the treatment effect.

Expected outcomes

Qualitative study: Accordingly to similar work (Cox, Henderson, Andersen, Cagliarini, & Ski, 2003), broad categories are expected to emerge from women’s reports: diagnosis struggle, health care dissatisfaction, depression, pain, relationship difficulties, fertility issues and financial burden. Primary outcomes: considering this study effort to focus intensively in beliefs and behaviors associated with women’s pain experience, we expect to find cognitive and behavioral themes providing further insight about women’s perceptions/ appraisals, main concerns and ways of dealing with symptoms/life situations. Secondary outcomes: we expect that outcome of this analysis will provide a closer and idiographic perspective about women who live with the disease, develop information that will contribute to clarification of the psychological identity of the disease, and identify main areas to address in the development of the group CBT.

Quantitative study: as reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis of CBTs for pain (Morley, Eccleston, & Williams, 1999), and suggested in previous studies (Denny & Khan, 2006; Kames, Rapkin, Naliboff, Afifi, & Ferrer-Brechner, 1990) it is expected that CBT will improve related quality of life in women diagnosed with endometriosis. Primary outcomes: we predict that conducting CBT, teaching women self-management skills, individual goal setting and providing a psycho-educational framework, will decrease pain, depression and anxiety levels, and improve active coping strategies. As developing active and positive coping helps stop catastrophization, we expect to potentiate pain adjustment(Kaatz, Solari-Twadell, Cameron, & Schultz, 2010) and enhance women’ self efficacy. Ultimately, considering changes in previous variables and the social support within a group therapy, we expect to promote social support and facilitate social integration. Provide a psychotherapeutic option for women who wish to manage their disease, Secondary outcomes: reduce unnecessary invasive surgeries that burden both individual women and the health care system as a whole.

DISCUSSION

The present study is included within a growing body of literature that highlights the need to better understand the endometriosis’ phenomenon on a psychological perspective, both in a quantitative and qualitative dimension (Hirsh, Ladipo, Bhal, & Shaw, 2001; Jones, Jenkinson, & Kennedy, 2004; D’Hooghe & Hummelshoj, 2006; Levy, Apgar, Surrey, & Wysocki, 2007). It is the authors’ intention to provide women a voice in describing their own symptoms and experiences, and develop a psychological approach to improve their pain disability and enhance health related quality of life. A cognitive behavioral approach within a multidisciplinary framework is presented. CBT is considered within a group format, and outpatient clinic approach. Women’s reports are one of the strongest dimensions of this study as it values their own appreciation of facts and needs in the design of the CBT. Current psychological approaches to endometriosis tend to perform their needs assessment recurring to objective measures, leaving aside complex and polysemous interpretations of the disease. Therefore, an interventional approach that derives from women’s needs and preferences may result in an enhanced health service. A type of assistance aligned with womens’ needs can help suppress present difficulties in the approach to medical services and promote disease knowledge, awareness and treatment (Mendes & Figueiredo, submitted).

REFERENCES

Atkins, D.C. (2009). The cutting edge. Clinical trial methodology: Randomization, intent-to-.treat, and random-effects regression. Depression and Anxiety, 26, 697-700. [ Links ]

Ballard, K., Lowton, K., & Wright, J. (2006). What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility, 86(5), 1296-301.

Banerjee J., Mallikarjunaiah, M.H., Murphy, J.M. (2010). Advanced Management Options for Endometriosis. Current Women’s Health Reviews, 6, 123-129. ,

N Wyman PA, Chamberlain P, Sloboda Z, MacKinnon DP, Windham A (2008). Methods for testing theory and evaluating impact in randomized field trials: intent-to-treat analyses for integrating the perspectives of person, place, and time. Drug Alcohol Depend, 95 (Suppl. 1), 74-104. [ Links ]

Louis, G.M., Hediger, M.L., Peterson, C.M., Croughan, M., Sundaram, R.,....., & Giudice, L.C. (2011). . Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertility and Sterility,96(2), 360-365. [ Links ]

Carpan, A. (1996). Learning to live with endometriosis: A grounded theory study. St John’s, NL: Memorial University of Newfoundland. Available from: MastersAbstracts International; 1527.

International Association for the Study of Pain. (2005). Psychological treatments (cognitive-behavioural and behavioural interventions). In Charlton, J.E. (Ed.), Core Curriculum for Professional Education in Pain (pp. 1-4). Seatle: IASP Press. [ Links ]

Cox, H., Henderson, L., Andersen, N., Cagliarini, G., & Ski, C. (2003). Focus groupstudy of endometriosis: struggle, loss and the medical merry-go-round. International Journal Nursing Practice, 9(1), 2-9. [ Links ]

D'Hooghe, T., Hummelshoj, L. (2006). Multi-disciplinary centres/networks of excellence for endometriosis management and research: A proposal. HumanReproduction, 21(11), 2743-8. [ Links ]

Denny E. (2004). Women’s experience of endometriosis. Journal of Advance Nursing,46, 641-8.

Denny, E., & Khan, K.S. (2006). Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence: What are the experiences of women with endometriosis? Journal of Obstetrics Gynaecology, 26(6), 501-506. [ Links ]

Direcção Geral de Saúde. (2008). Circular Normativa Nº 11//DSCS/DPCD – Programa Nacional de Controlo da Dor. [ Links ]

Dysvik, E., Vinsnes, A.G., & Eikeland, O.J. (2004). The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary pain management programme managing chronic pain. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 10, 224-234. [ Links ]

Evers, J.L. (1994). Endometriosis does not exist: all women have endometriosis. Human Reproduction, 9, 2206-9. [ Links ]

Fourquet, J., Báez, L., Figueroa, M., Iriarte, I., & Flores, I. (2011). Quantification of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life and workproductivity. Fertility and Sterility, 96(1), 107-111. [ Links ]

Fukunaga, M. (2011). Paratesticular endometriosis in amanwith a prolonged hormonal therapy for prostatic carcinoma. Pathology Research & Practice, [Epub ahead of print] [ Links ].

Gambone, J.C., Mittman, B.S., Munro, M.G., Scialli, A.R., Winkel, C.A., & theChronic Pelvic Pain/Endometriosis Working Group. (2002). Consensusstatement for the management of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosisproceedings from an expert.panel consensus process. Fertility and Sterility, 78 (5), 961-962. [ Links ]

Gao, X., Outtley, J., Botteman, M., Spalding, J., Simon, J.A., Phasos, C.L. (2006).Economic burden of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility, 86, 1561-1572. [ Links ]

Gerlinger, C., Schumacher, U., Faustman, T., Colligs, A., Schmitz, H., & Seitz, C. (2010). Defining a minimal clinically important difference for endometriosisassociated pelvic pain measured on a visual analog scale: Analyses of two placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 138-144. [ Links ]

Gylmour, J.A., Huntington, A., & Wilson, H.V. (2008). The impact of endometriosis on work and social participation. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 14, 443-448. [ Links ]

Hadfield, R., Mardon, H., Barlow, D., Kennedy, S. (1996). Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and the UK. Human Reproduction, 114, 878-880. [ Links ]

Hirsh, K.W., Ladipo, O.A., Bhal, P.S., & Shaw, R.W. (2001). The management of endometriosis: A survey of patients’ aspirations. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology,1(5), 500-503.

Hsieh, H.F., & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. [ Links ]

Huntigton, A., & Gimour, J.A. (2005). A life shaped by pain: Women and endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 1124-132. [ Links ]

Husby, G.K., Haugen, R.S., & Moen, M.H. (2003). Diagnostic delay in women withpain and endometriosis. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica, 827, 649뉕. [ Links ]

Jones, G., Jenkinson, C., & Kennedy, S. (2004). The impact of endometriosis upon quality of life: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 25, 123-133. [ Links ]

Kaatz, J., Solari-twadell, A.Q., Cameron, J., & Schultz, R. (2010). Coping With Endometriosis. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 39(2), 220-226 [ Links ]

Kames, L.D., Rapkin, A.J., Naliboff, B.D., Afifi, S., Ferrer-Brechner, T. (1990). Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary pain management program for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Pain, 41(1), 41-6. [ Links ]

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ, 311, 299-302. [ Links ]

Klinkhammer-Schalke, M., Koller, M., Ehret, C., Steinger, B., Ernst, B., Wyatt, J.C. (2008). Implementing a system of quality-of-life diagnosis and therapy for breast cancer patients: results of an exploratory trial as a prerequisite for a subsequent RCT. British Journal of Cancer, 99(3), 415-22. [ Links ]

Kumar, A., Gupta, V., & Maurya, A. (2010). Mental health and quality of life in chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis patients. Journal of Projective Psychology Mental Health, 17, 153-157. [ Links ]

Lapp, T. (2000). ACOG Issues Recommendations for the management of endometriosis. American Family Physician, 62(6), 1431-432. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Spinger Publishing. [ Links ]

Levy, B.S., Apgar, B.S., Surrey, E.S., & Wysocki, S. (2007). Endometriosis and chronic pain: A multispecialty roundtable discussion. The Journal of Family Practice, 56(Suppl.3), 3-13. [ Links ]

Lorençatto, C.,Petta, C.A., Navarro, M.J., Bahamondes, L., & Matos, A. (2006), Depression in women with endometriosis with and without chronic pelvic pain. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica, 85(1), 88-92. [ Links ]

Mao, J.A., & Anastasi, J.K. (2010). Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: The role of the advanced practice nurse in primary care. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 22, 109-116. [ Links ]

Marsh, E.E., & Laufer, M.R. (2005). Endometriosis in premenarcheal girls who do nothave an associated obstructive anomaly. Fertility and Sterility, 83, 758-760. [ Links ]

Martin C.E., Johnson E., Wechter, M.E., Leserman J., & Zolnoun, D.A. (2011).Catastrophizing: a predictor of persistent pain among women with endometriosis at 1 year. Human Reproduction, 26(11), 3078-3084. [ Links ]

McCracken, L.M., & Turk, D.C. (2002). Behavioral and Cognitive-BehavioralTreatment for Chronic Pain. Spine, 27(22), 2564-2573. [ Links ]

Mendes, N, & Figueiredo, B. Endometriosis and women’s experience: Review on qualitative literature. Qualitative Health Research, (submitted).

Metzger, D.A. (1997). Treating endometriosis pain: A multidisciplinary approach.Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology, 15(3), 245-50. [ Links ]

Morley, S., Eccleston, C., & Williams, A. (1999). Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviourtherapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain, 80, 1-13. [ Links ]

National Endometriosis Society. What is Endometriosis? Available online from http://www.endometriosis-uk.org/information/whatisit.html. Accessed on 08/01/2012. [ Links ]

Nnoaham, K.E., Hummelshoj, L., Webster, P., D'Hooghe, T., Cicco, Nardone, F., .... & Zondervan, K.T.(2011). Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries.Fertility and Sterility, 96(2), 366-373. [ Links ]

Nunnink S., & Meana M., (2007). Remembering the pain: Accuracy of pain recall in endometriosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 28 (4), 201 [ Links ]

Ozawa, Y., Murakami, T., Terada, Y., Yaegashi, N., Okamura, K., Kuriyama, & S., Tsuji, I. (2006). Management of the pain associated with endometriosis: An update of the painful problems. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 210(3), 175-88. [ Links ]

Pais-Ribeiro, J. (2005). O importante é a saúde: Estudo de adaptação de uma técnica de avaliação do Estado de Saúde – SF-36. Merck Sharp & Dohme Fundation. [ Links ]

Pinkert, T.C., Catlow, C.E., & Straus, R. (1979). Endometriosis of the urinary bladderin a man with prostatic carcinoma. Cancer, 43(4), 1562-1567. [ Links ]

Pugsley, Z., Ballard, K. (2007). Management of endometriosis in general practice:The pathway to diagnosis. The British Journal of General Practice, 57(539), 470- [ Links ]6.

Siedentopf, F., Triverdian, N., Rucke, M., Kentenich, H., & Arck, P.C. (2008). Immunestatus, psychological distress and reduced quality of life in infertile patients with endometriosis. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 60, 449-461. [ Links ]

Sepulcri, P., & Amaral, V.F. (2009). Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life in women with pelvic endometriosis. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 142(1), 53- [ Links ]6.

Sullivan, M.J., Thorn, B., Haythornthwaite, J.A., Keefe, F., Martin, M., Bradley, L.A., & Lefebvre, J.C. (2001). Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 17, 52–64. [ Links ]

The American Group Psychotherapy Association. (2007). Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy. Available online from http://www.agpa.org/guidelines/index.htm Accessed on 02/04/2012. [ Links ]

Thorn, B.E., & Kuhadja, M.C. (2006). Group Cognitive Therapy for Chronic Pain. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 62(11), 1355-1366. [ Links ]

Turk, D.C., & Okifuji, A. (1999). A cognitive-behavioral approach to pain management. In P.D. Wall, & R. Melzack (Eds.), Textbook of Pain (pp. 1431-1443). New York, Churchill Livingstone. [ Links ]

Turk, D.C., Wilson, H.D., & Cahana, A. (2011). Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain.Lancet, 377, 2226-35. [ Links ]

Zarnegar, R., & Daniel, C. (2005). Pain management programmes. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical care & Pain, 5(3), 80-83. [ Links ]

Recebido em 4 de Março de 2010/ Aceite em 12 de Fevereiro de 2011