Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.13 no.1 Lisboa 2012

What is lost when psychosomatics is replaced by somatization?

O que se perde quando a psicossomática é substituída pela somatização?

Lazslo Ávila, Donati, F., & Cordeiro, J.A.

Departamento de Psiquiatria e Psicologia Médica. Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, Brasil

Contato:lazslo@terra.com.br

ABSTRACT

To critically review scientific publications from the last five years to identify the main themes linked to psychosomatics and somatization with the purpose of analyzing the meaning of tendencies manifested by these themes and their distribution. A systematic review of abstracts linked to the MEDLINE, LILACS and SciELO databases from 2004 to 2008, using MeSH, the structured vocabulary proposed by the National Library of Medicine, to create 38 content categories in order to classify the papers. Principal component statistical analysis was performed to indicate the structuring order of the themes. We found an expressive dominance of the use of the term ‘somatization’, particularly in MEDLINE, with an accentuated tendency to substitute ‘psychosomatics’ and an overall predominance of psychiatry over other specialties or approaches. Many different perspectives on psychosomatic phenomena are progressively becoming less significant with a concentration of research themes in only four large clusters of categories: 1) ‘psychiatry + psychosomatics’; 2) ‘psychiatry - psychosomatics’; 3) ‘medical specialties + treatment – subjectivity + scales + psychosomatics - psychiatry’ and 4) ‘psychiatry × medical specialties + subjectivity + psychosomatics + psychiatry × psychosomatics - psychiatry’. We demonstrate that the underlying tendency of present-day research is to eradicate the prefix ‘psycho’ from psychosomatic studies, with the remaining expression ‘somatization’ becoming more and more indicative of a strictly biological, physiological and positivistic viewpoint.

Key words- Classification - Psychosomatic Medicine – Psychosomatics – Somatization – MeSh - Principal Component Analysis

RESUMO

Revisão crítica das publicações científicas dos últimos cinco anos visando identificar os principais temas vinculados à psicossomática e à somatização, com o propósito de analisar o significado das tendências manifestadas por esses temas e sua distribuição.

Revisão sistemática dos resumos publicados nos bancos de dados MEDLINE, LILACS e SciELO, de 2004 a 2008, utilizando o MeSH, vocabulário estruturado proposto pela National Library of Medicine, e estabelecendo 38 categorias de conteúdo para a classificação dos artigos. Análise estatística do principal componente foi realizada para indicar a ordem estruturante dos temas.Encontramos uma expressiva predominância do uso do termo "somatização", particularmente no MEDLINE, com uma acentuada tendência de substituir "psicossomática" e um predomínio da psiquiatria sobre as outras especialidades ou abordagens. Muitas perspectivas distintas sobre os fenômenos psicossomáticos estão se tornando progressivamente menos significativas, com uma concentração dos temas de pesquisa em apenas quatro grandes agrupamentos de categorias: 1) ‘psiquiatria + psicossomática’; 2) ‘psiquiatria – psicossomática’; 3) ‘especialidades médicas + tratamento – subjetividade + escalas + psicossomática -psiquiatria’ and 4) ‘psiquiatria × especialidades médicas + subjetividade + psicossomática + psiquiatria × psicossomática - psiquiatria’.Demonstramos que a tendência subjacente da pesquisa contemporânea é a de erradicar o prefixo "psico" dos estudos psicossomáticos, com a expressão remanescente "somatização" tornando-se cada vez mais indicativa de um ponto de vista estritamente biológico, fisiológico e positivista.

Palavras Chave - Classificação – Medicina Psicossomática – Psicossomática – Somatização – MeSH – Análise do Principal Componente

Psychosomatics, the field of knowledge dedicated to the investigation of mind-body relationships, has followed a long course with many obstacles and achievements. Historically, psychosomatics was born with the first assumptions of German psychiatrist Johann Heinroth in 1818 and 1828 (Shorter, 1995; Steinberg, 2007). However, this area became fully established with the research of the Chicago Psychosomatic School founded by Franz Alexander (1950) and with the studies of the psychiatrist Helen Flanders Dunbar (1943) in New York during the 1920s and 1930s. The pioneer of psychoanalytical psychosomatics at the beginning of the 20th century, considered by some as the real ‘father’ of psychosomatics German physician Georg Groddeck (Groddeck, 1950; Groddeck, 1977), remains largely unknown, despite of the originality of his work (Ávila, 2003; Grossman & Grossman, 1965).

After a productive beginning, and with the support of investigations by the cardiologists Friedman and Rosenman (1974), who created the ‘Type A’ and ‘Type B’ personality theory, psychosomatics entered the curricula of many medical schools throughout the world.

In England, the Hungarian émigré Michael Balint (Balint, 1957) introduced innovative practices in hospitals using his group methodology to prepare doctors to better understand the emotional life of their patients by linking emotional conflicts to disease processes and to the interpersonal aspects of treatment. His and other psychosomatic models spread and resulted in many publications.

Nevertheless, this wave of interest had almost vanished by around the end of the 1950s, with the few remaining researchers in the United States, Europe (mainly England, France and Germany) and Latin America, producing isolated studies.

During the 1960s, psychosomatic perspectives were gradually abandoned, probably due to the huge scientific-technological advances that provoked profound changes in the way most physical and mental diseases were conceived in their etiology, course and treatment. The number of medical specialties started to expand quickly from the beginning of the 20th century with several consequences. First, the focus of each specialty became more and more restricted and the specialties were even gradually broken down into sub-specialties thus creating greater distances between each area and hindering any global view on health. Secondly, the connections between each disease and the psychosocial environment became blurred. Finally, the body-mind relationship in the patho-dynamics was eclipsed with the progressive elucidation of many biochemical and biophysical determinants. This is acknowledged by many authors, including Gottlieb (2003):

"Today we recognize the need for more than one set of explanatory propositions, but we also recognize that our views of the fundamental relationships between mind and body, between psyche and soma, have changed dramatically, certainly since the end of the nineteenth century, but even more so over the past twenty-five years" (p. 877).

One consistent point stressed by Psychosomatic Medicine is the susceptibility to diseases, but as Sheps, Creed & Clouse (2004) remark, this is nowadays normally linked to the tendencies to somatization. Psychological or psychopharmacological therapies are considered effective only when clear psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety or depression, emerge.

Although unquestionably desirable, holistic perspectives frequently clash with the modern approaches of health professions, in particular medicine, which are becoming more and more technologically orientated and specialized.

There is an urgent cry to fill the epistemological gap between explanatory systems for the multifold aspects of diseases. Although it is acknowledged that several psychosocial, life-style, and socio-cultural characteristics contribute to pathological processes, in particular in respect to the notion of risk, the truth is that very little is known about the dynamics of interactions between the internal and external elements linked to the causation of diseases (Ávila, 2006; ; Escobar & Gureje, 2007; Kroenke, 2007; Leiknes, Finset, Moum, & Sandanger, 2008).

In this context of progressively more complex questions concerning concurring factors, psychosomatic medicine and holistic approaches do not play a significant role in present-day scientific discussion in spite of the large numbers of publications in these fields.

The psychosomatic movement gained momentum with the launching of specialized journals, such as Psychosomatic Medicine in 1939, Psychosomatics in 1953, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics also in 1953, Journal of Psychosomatic Research in 1956, among others, as well as the foundation of several associations, which brought together physicians and other health professionals around the world.

In the 1990s, advances in immunology and endocrinology, in addition to new perspectives on the etiology of mental and physical illnesses, led to the proposal of a new integrative discipline: Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology (Dantzer, 2005; Houtveen, Kavelaars, Heijnen, & van Doonen, 2007; Rief & Barsky, 2005; Siegel, Antoni, Fletcher, Mahler, Segota, & Klimas, 2006). Several studies reported that a) psychiatric disorders are associated to neurological disturbances, implying changes in both specialties and linking mental processes to the functioning of the brain; b) hormonal activities are connected with many emotional and behavioral patterns and c) the association of the immune function with the brain and other organs is extremely complex. But, no reliable biological markers have been found proving this articulation and thus no definite claim can be made. There is not enough evidence to allow clear statements about the onset, influence and differentiation between mental symptoms and physical signs of diseases. It is thus risky to dismiss any affective or behavioral expression from a putative underlying neurological process, both in health and illness.

Hence, in spite of its suggestive name, of the inherent inter-disciplinary possibilities and of the numbers of professionals and patients that would benefit from it, the fact is that psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology is still only good for further research. At the same time, the emerging branch of neuro-sciences seems to want to embrace an excessive amount of situations and this further contributes to a drop of interest in the psychosomatic perspective.

Nevertheless, similar to what once led Charcot to declare about hysteria, ‘this does not impede the fact that it exists’, psychosomatic symptoms are very frequently seen in the general population, even in emotionally stable individuals (Creed, Mayou, & Hopkins, 1995; Faravelli, Catena, Scarpato, & Ricca, 2007; Levi, 1971; Melmed, 2001 ).

Another critical factor associated to the relative decline is, beyond any doubt, the importance given by disease classification manuals to psychosomatics, both in research and in the organization of health services. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD 10) and the Diagnostic Statistical Manual for Mental Diseases, 4th edition revised (DSM IV) established their operational criteria removing all psychosomatic content. In the Introduction of the ICD 10, the authors declare that they decided to avoid the use of the expressions ‘psychogenic’ and ‘psychosomatic’ with the justification that these terms have different meanings in different languages and in different psychiatric traditions, and they insist that ‘psychosomatic’ would imply that psychological factors only exist in the processes of some diseases, while they consider that they have a role in the occurrence, course and evolution of all diseases. The DSM also abandoned the use of these expressions.

With the Classifications came the final blow; psychosomatics has since then been seen as an excessively generic designation, too vague to sustain a diagnosis and too universal to explain any particular disease. Hence, psychosomatics became useless or irrelevant as a scientific concept. From this moment on, somatization and somatoform disorders took much of its place in scientific research and in the clinical practice.

Contradictorily, Psychosomatic Medicine was recently recognized as a subspecialty of psychiatry by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and regained public recognition in the United States. In other countries there are consistent advances in consultant liaison psychiatry (C/L), with the creation of many departments in general hospitals that aim to discuss the interdisciplinary aspects of different symptoms of diseases (Barkow et al., 2004; de Waal, Arnold, Eekhof, & van Hemert, 2004; Fink, Hansen, & Oxhoj, 2004; Jorsh, 2006; Löwe et al., 2008; Wilhelm, Finch, Davenport, & Hickie, 2008; Zastrow et al., 2008).

But the concept of somatization seems to have become hegemonic, maybe due to a scientific trend or as a tendency to reorganize the way in which mind-body relationships are to be conceived. So, it is relevant to discuss the presentations of both psychosomatics and somatization in scientific publications and the structuring order chosen by researchers.

Coelho and Ávila (2007) published a study with the aim of discussing how somatization was being debated in widespread contexts and medical situations. For this, the authors reviewed publications from 2001 to 2004 in the MEDLINE and LILACS databases searching using the keywords ‘somatization’, ‘somatoform disorders’ and ‘psychosomatics’. Of a total of 775 abstracts, 191 papers (24.6%) were identified in the area of psychiatry, followed by 139 papers (17.9%) in other medical specialties, in particular neurology (34 papers - 4.4%) and gastroenterology (28 papers - 3.6%). In order of importance, the third item was therapeutics, with 55 papers (7.1%), followed by the items pain (53 papers - 6.8%) and etiology (51 papers - 6.6%). The study concluded by stressing the necessity of further research because of the high costs to health services, to clear up controversies related to this question, to help to simplify diagnoses and to improve the clinical approach to somatizing patients.

The aims of our current study were to update this critical review of the specialized literature, tracking papers published in databases in the following five years, that is, from 2004 to 2008, with the goal of comparing the frequencies of categories manifested in the papers and to answer which direction is being taken in current research. Thus, we will be able to better understand what is happening with the concept of psychosomatics, as well as with its heir and substitute, the concept of somatization.

The objectives of this critical review are: 1) to determine the number, frequency and themes appearing as scientific research in the five years from 2004 to 2008 in relation to psychosomatics and somatization; and 2) to analyze the meaning of the tendencies manifested in the themes and in the distribution of these subjects in three major databases, MEDLINE, the Latin America and Caribbean database, LILACS, and the Brazilian electronic online library (SciELO).

METHODS

A systematic review of research papers involving somatization and psychosomatics was made and a classification of content categories was proposed. Using the MEDLINE, LILACS and SciELO databases, we searched using the following keywords: somatization, somatization disorders, somatoform disorders, psychosomatics and classification, in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese. We focused our research on papers produced between January 1st, 2004 and the end of 2008.

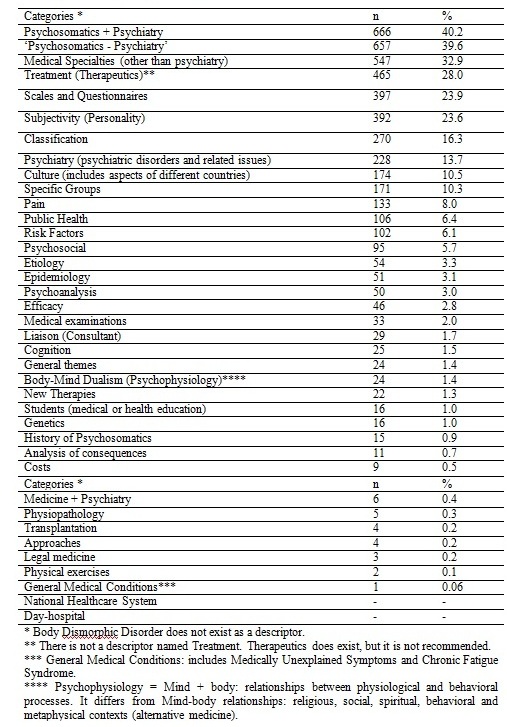

We finished data collection on July 1st, 2009, with a total of 1658 abstracts. After a careful study of the abstracts, we classified all the works in categories associated to somatization and psychosomatics. We used the structured three language vocabulary known as DeCS (Pan American Health Organization – translation of the MeSH, Medical Subject Headings, from the National Library of Medicine) to create 38 categories of classification (see Table 1). Most papers received two or more categories, depending on the themes discussed by the authors.

Statistical analysis employed the computer software, Minitab15 (Minitab, Inc.; http://www.minitab.com). Simple contingency tables were constructed for data description and principal components analysis (PCA) was performed to determine structuring factors of the relationships between keywords and databases. The medians of the first four factor scores were compared in respect to different databases. A significance level for a p value < .05 was adopted.

RESULTS

The total number of abstracts found in this period and classified was 1658 in 550 journals; 1575 (95%) in MEDLINE, 53 in LILACS (3.2%) and 30 (1.8%) in SciELO. Of these abstracts, 1.6% was classified in one content category, 22.4% in 2 categories, 58.7% in 3 categories, 22.4% in 4 categories and 1.1% in 5 categories. Table 1 lists the different categories and the frequency of abstracts classified in each category.

Percentage and frequency of categories identified from the Abstracts.

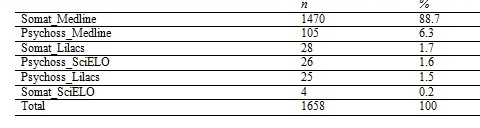

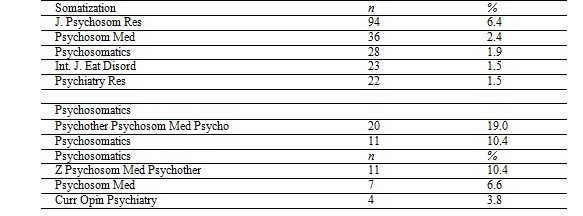

Table 2 shows the frequency of keywords associated to either somatization or psychosomatics for the Medline, LILACS and SciELO databases.

Table 2 – Percentage and frequency of keywords related to the different databases.

The journals linked to the Medline database that most commonly used the keywords ‘somatization’ and ‘psychosomatics’ are shown in Table 3. The frequency of the use of these keywords in journals linked to the other databases were insignificant as around 95% of all journals related to this subject are linked to the Medline database.

Table 3

The main Journals in Medline utilizing the keywords somatization and psychosomatics (Somat_Medline and Psicoss_Medline)

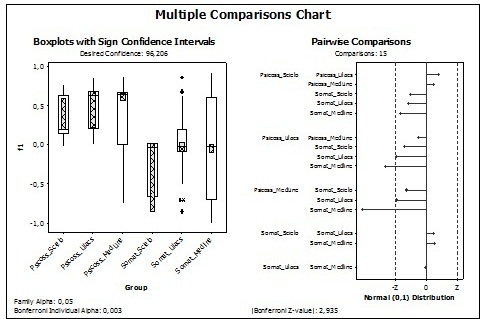

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a geometric method based on the principle of reducing a number of observed variables to a smaller number of artificial variables (called principle components - PC) that will account for most of the variance in the observed variables. The principle components are then used in subsequent analysis. PCA was applied to search for distribution structures of the articles over the observed years based on the covariance matrix of the keyword indicators. PCA orders the PC (factors) from the first which entails the greatest total variation (sum of the 38 variances of categories) to the last with the smallest explanation of the total variation. The first PC explains 19% of the total variation, the second 11%, the third 10% and the fourth 9%, with a cumulative explanation of 49%, thus providing a good reduction of the dimensionality of the problem from 38 to 4.

A pattern of behavior is assigned to each factor by analyzing the factor loads (FL) it gives to the categories. Amongst all factor loads the first factor gives to all categories, ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ (FL = 0.667) and ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ (FL = -0.686) entail 92% of its composition, which means the behavior of this factor is to set ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ against ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ with basically the same strength, which in terms of correlation means a strong negative action between these two categories.

The second factor is expressed as an ordered combination Medical Specialties (0.617), Subjectivity (–0.468), Treatment (0.432), Scales (–0.356) and ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ (–0.223), which can be expressed as a contraposition {0.627×Medical Specialties + 0.432×Treatment} – {0.468×Subjectivity + 0.356×Scales + 0.223בPsychosomatics-Psychiatry’}. The third expresses the antithesis Treatment × 0.750 - {Medical Specialties×0.547 + Scales×0.241 + Psychiatry×0.176}, and the fourth Psychiatry×0.564 – {0.418×Medical Specialties + 0.470×Subjectivity + 0.344בPsychosomatics+Psychiatry’ + 0.280בPsychosomatics-Psychiatry’}.

Each one of these four factors, through the patterns of behavior by separating the categories according to certain distributional structures, can discriminate the database, as for instance, Factor 1 which has a significantly smaller median for Somat.MedLine than for Psychos.Lilacs (p value < .00005), and also smaller than for Psychos.MedLine (p value < .0001), and as Factor 1 is the combination ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’×0.667 - (‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’)×0.686 the smaller median indicates less references for ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ and more for ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ in Somat.MedLine. The opposite occurs for Psychos.Lilacs and Psychos.MedLine.

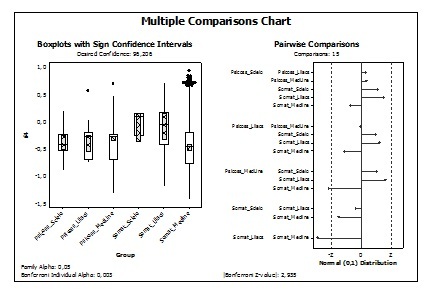

Figure 1

Sign Confidence Intervals and Pairwise Comparisons – Psychosomatics and Somatization

There is no evidence that Factors 2 (p-value=0.39) and 3 (p-value=0.052) have different medians according to 'groups'.

Nonetheless the low explanation of the total variation (9%) by Factor 4 indicates that it has significantly higher medians in Psychos.MedLine (p-value<0.00005) and Somat.Lilacs (p-value=0.0018) than in Somat.MedLine, and as Factor 4 is basically Psychiatry×0.564 – {0.418×Medical Specialties + 0.470×Subjectivity + 0.344בPsychosomatics+Psychiatry’ + 0.280בPsychosomatics-Psychiatry’} in both databases where the medians are higher, there are more references to Psychiatry and less of Medical Specialties, Subjectivity, ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ and ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’, than Somat.MedLine, where the opposite occurs.

Figure 2

Sign Confidence Intervals and Pairwise Comparisons – Databases

DISCUSSION

In this study we found that the combination of the contents ‘Psychosomatics’ and ‘Psychiatry’ is the most common trend in recent publications with 40.2% of all abstracts fitting into this category. Statistical analysis of the results demonstrated that the first component factor, which is basically the opposition between ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ and ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ represents 19% of the abstracts, meaning that this is a structure that aggregates the papers. This finding shows the underlying tendency of the themes chosen by current researchers, with ‘psychiatrization’ of the subject. We interpret this as the progressive dominance of this specialty over psychosomatic phenomena, with the concomitant tendency to replace the word psychosomatic by the term somatization. Historically, psychiatry was the field in medicine closest to mental issues and thus the one closest to human sciences, with investigation criteria far beyond the merely physiological. But, modern psychiatry has a strong link to organic structures, it investigates biological substrates of mental processes, considering the brain as the ultimate and essential origin of mental phenomena, whereas psychodynamically-directed psychiatry is reducing and losing space and relevance. In the field of psychosomatics, this represents the abandonment of subjectivity and related matters and the adoption of physiological aspects as the essential reference, that is, neurotransmitters in the place of abstractions, molecules instead of symbols.

The category ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ represents the second most common theme in all three databases, with 39.6% of the content. But this was exactly the focus of the study, the general classification governing the selection of papers. The second factor in the component factor analysis is the contraposition of Medical Specialties combined with Treatment against Subjectivity + Scales + ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’. This factor represents 11% of the sample. It is very important to discover exactly what is being discussed under the umbrella of ‘psychosomatics’ as the general label. We interpret this as a change in the way psychosomatics is conceived, with a devaluation of the ‘psycho’ features and a dominance of the ‘somatic’. That is to say, questions not strictly organic (‘somatic’) are disappearing from the focus of research and being ignored as part of the explanation of these phenomena. This is also revealed by the low indices of certain categories such as Subjectivity, Mind and Body dualism, Psychoanalysis, Psychosocial Factors, or Culture.

In the third place, representing 10% of the distributive structure, the category Treatment is set against Medical Specialties, plus Scales and Inventories and plus Psychiatry. In our view, this suggests that among different specialties, psychosomatics is mostly considered as an issue to be objectively examined, using inventories and quantitative measures. The treatment of the symptoms seems to be of greater concern than theoretical or conceptual investigations. The consequence is the development of evaluative and curative approaches, converting psychosomatic illnesses to the equivalent of any other somatic disease: something to be exclusively treated and not to be analyzed and understood during treatment.

The fourth aspect shown by the statistical analysis demonstrates that the keyword ‘somatization’, the category ‘psychiatry’ and the database MEDLINE are strongly associated, whereas in the other databanks, LILACS and SciELO, there is a presentation of papers grouping the Medical Specialties, Subjectivity, ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’ and ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ categories. This distribution shows that ‘somatization’ progressively substitutes ‘psychosomatics’ in the best known database. In the Latin-American databases, there is a relative imbalance in the utilization of both keywords, and even a preference for the classification ‘Psychosomatics-Psychiatry’ without the connection ‘Psychosomatics+Psychiatry’. Inversely, MEDLINE consecrates ‘somatization’ and tends to link psychosomatics with psychiatry with less research being dedicated to psychosomatics as an area in its own right.

What this means, in our contention, is that psychiatry is the basic reference of present-day researchers, with expressiveness in face of the other medical specialties and also in face of the studies on personality, subjectivity and the psychosocial approaches to this area. The more ‘psychiatric’ the discourse and practice of treatment of the psychosomatic phenomena, the greater the dominance of a viewpoint that sees the body (somatic) as the essence, and the psychological dimension as a mere epiphenomenon, secondary to the biological aspect. The exclusion of the psychical component seems to be the essential trait characterizing the homogeneity of perspectives of authors that publish in MEDLINE, compared to authors publishing in other databases.

Our analysis showed that several classifications, such as ‘day-hospital’, ‘general medical conditions’, ‘physical exercises’, ‘legal medicine’, ‘different methods of approach’, ‘costs’, ‘medicine+psychiatry’, and ‘analyses of consequences’ represent, less than 0.9% of the occurrences each and can be dismissed as irrelevant when considering tendencies underlying research. Thus, although they appear as possibilities of investigation, they do not influence the general direction of research.

In synthesis, we can state that ‘somatization’ is the predominant keyword in this field; MEDLINE is the most used database in regards to number of publications and ‘psychiatry+psychosomatics’ is the main category organizing the structure of distribution of papers published in the five years from 2004 to 2008. In our view, these aspects command the composition of contemporary tendencies displacing a particular quality, the quality directed towards psychosocial and psychodynamic aspects instead of strictly biological ones, to the scientific periphery of psychosomatic research. We consider that the adoption of the term ‘somatization’ is not only a scientific fad, but a significant bias of ‘medicalization’ and ‘psychiatrization’. The marginalization of the contribution of the human sciences, in particular anthropology, sociology, psychology and psychoanalysis, leads to psychosomatic studies becoming restricted by the positivistic viewpoint. Thus, the historical dimension, so relevant in these sciences, disappears from the design and analyses of psychosomatic research.

It is not innocent to erase ‘psycho’ from psychosomatics. With the widespread use of the concept of somatization, all the richness of the psychosomatic phenomena is at risk of being reduced to a minor psychiatric disorder.

REFERENCES

Alexander, F. (1950). Psychosomatic medicine: its principles and applications. New York: W. Norton. [ Links ]

Ávila, L. A. (2003). Georg Groddeck: originality and exclusion. History of Psychiatry; 1453, 83-101. [ Links ]

Ávila, L. A. (2006). Somatization or Psychosomatic Symptoms? Psychosomatics; 47, 163-166. [ Links ]

Balint, M. (1957). The Doctor, his patient and the illness. London: Churchill Livingstone. [ Links ]

Barkow, K., Heun, R., Ustün, T. B., Berger, M., Bermejo, I., Gaebel, W., Härter, M., Schneider, F., Stieglitz, R. D, & Maier, W. (2004). Identification of somatic and anxiety symptoms which contribute to the detection of depression in primary health care. European Psychiatry, 19, 250-157. [ Links ]

Coelho, C. L. S., & Ávila, L.A. (2007). Controvérsias sobre a somatização. Revista de Psiquiatria Cínica; 34, 278-284. [ Links ]

Creed, F., Mayou, R., & Hopkins, A. (Eds.) (1995). Medical symptoms not explained by organic disease. London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of Physicians of London. [ Links ]

Dantze, R. (2005). Somatization: a psychoneuroimmune perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30, 947-952. [ Links ]

de Waal, M. W., Arnold, I. A, Eekhof, J. A., & van Hemert, A. M. (2004). Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 470-476. [ Links ]

Dunbar, H. F. (1943). Emotions and bodily changes: a survey of literature on psychosomatic interrelationships 1910-1933. New York: Columbia. [ Links ]

Escobar, J. I, & Gureje, O. (2007). Influence of cultural and social factors on the epidemiology of idiopathic somatic complaints and syndromes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 841-845. [ Links ]

Faravelli, C., Catena, M., Scarpato, A., & Ricca, V. (2007). Epidemiology of life events: life events and psychiatric disorders in the Sesto Fiorentino study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76, 361-368. [ Links ]

Fink, P., Hansen, M. S., & Oxhoj, M. L. (2004). The prevalence of somatoform disorders among internal medical inpatients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 413-418. [ Links ]

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. (1974). Type A behaviour and your heart. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Gottlieb, RM. (2003). Psychosomatic medicine: the divergent legacies of Freud and Janet. Jourtnal of the American Psychoanalytical Association, 51, 857-881. [ Links ]

Groddeck, G. (1950). The Book of the It. London: Vision Press. [ Links ]

Groddeck, G. (1977). The meaning of illness. Selected psychoanalytic writings. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis. [ Links ]

Grossman, C. L, & Grossman, S. (1965). The wild analyst: the life and work of Georg Groddeck. New York: George Braziller. [ Links ]

Houtveen, J. H, Kavelaars, A., Heijnen, C. J, & van Doonen, L. J. (2007). Heterogeneous medically unexplained symptoms and immune function. Brain Behaviour and Immunity, 21, 1075-1082. [ Links ]

Jorsh, M. S. (2006). Somatoform disorders: the role of consultation liaison psychiatry. International Review of Psychiatry, 18, 61-65. [ Links ]

Kroenke, K. (2007). Somatoform disorders and recent diagnostic controversies. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 30, 593-619. [ Links ]

Leiknes, K. A, Finset, A., Moum, T., & Sandanger, I. (2008). Overlap, comorbidity, and stability of somatoform disorders and the use of current versus lifetime criteria. Psychosomatics, 49, 152-162. [ Links ]

Levi, L. (Edit). (1971). Society, stress and disease. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Löwe, B., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Mussell, M., Schellberg, D., & Kroenke, K. (2008). Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30, 191-199. [ Links ]

Melmed, R. N. (2001). Mind,bBody and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rief, W., & Barsky, A. J. (2005). Psychobiological perspectives on somatoform disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology; 30, 996-1002. [ Links ]

Sheps, D. S., Creed, F., & Clouse, R. E. (2004). Chest pain in patients with cardiac and noncardiac disease. Psychosomatic Medicine; 66, 861-867. [ Links ]

Shorter, E. (1995) Somatoform disorders. In: Berrios, GE & Porter, R. (Eds.). A history of clinical psychiatry – the origin and history of psychiatric disorders. (476-89). New York: NYUP. [ Links ]

Siegel, S. D., Antoni, M. H., Fletcher, M. A., Mahler, K., Segota, M. C, & Klimas, N. (2006). Impaired natural immunity, cognitive dysfunction, and physical symptoms in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: preliminary evidence for a subgroup? Journal of Psychosomatic Research; 60, 559-566. [ Links ]

Steinberg, H. (2007). Die geburt des wortes ‘psychosomatisch’ in der medizinischen weltliteratur durch Johann Christian August Heinroth. Fortschritte der Neurologie- Psychiatrie; 75, 413-417.

Wilhelm, K. A., Finch, A. W., Davenport, T. A., & Hickie, I. B. (2008). What can alert the general practitioner to people whose common mental health problems are unrecognised? The Medical Journal of Australia; 188, S114-118. [ Links ]

Zastrow, A., Faude, V., Seyboth, F., Niehoff, D., Herzog, W., & Löwe, B. (2008). Risk factors of symptom underestimation by physicians. Journal of Psychosomatic Research; 64, 543-551. [ Links ]

Recebido em 29 de Novembro de 2011/ Aceite em 25 de Maio de 2011