Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.18 no.3 Lisboa dez. 2017

https://doi.org/10.15309/17psd180319

Wilson's sex fantasy questionnaire: Portuguese validation and gender differences

Wilson's sex fantasy questionnaire: validação Portuguesa e diferenças de género

Mariana Amaral Saramago1, Jorge Cardoso2, Filipa Pimenta1, & Isabel Leal 1

1William James Center for Research, ISPA- Instituto Universitário, Lisboa, Portugal. (mariana.amaral.saramago@gmail.com) (filipa_pimenta@ispa.pt) (ileal@ispa.pt)

2Centro de investigação interdisciplinar Egas Moniz (CiiEM), Instituto Superior de Ciências da Saúde Egas Moniz, Monte de Caparica, Portugal. (jorgecardoso.psi@gmail.com)

Endereço para Correspondência

ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this study was to validate a Portuguese version of the Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire. Afterwards, we assess the fantasies' frequency based on gender differences. A community sample of 1220 Portuguese men and women completed the questionnaire with 40 items. Factor exploratory and confirmatory analysis, as well as comparative statistics for independent samples, were applied with the IBM SPSS Statistics and AMOS software (both v. 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il., USA). The final structure with 24 items distributed amongst four factors showed overall good psychometric properties (in terms of factorial validity, reliability and sensitivity) and questionable convergent and discriminant validity. The independent samples t-test showed gender differences regarding sexual fantasies frequency. This research provides a validated version of the Portuguese Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire. It also shows some common and disparate gender differences compared to other research. Further studies are need in order to confirm this structure amongst other samples (e.g., clinical and forensic).

Keywords: gender differences, sexual fantasies, validation, wilson sex fantasy questionnaire.

RESUMO

O principal objetivo deste estudo foi a validação da versão Portuguesa do Questionário de Fantasias Sexuais de Wilson. Posteriormente, analisamos a frequência das fantasias em função do género. Uma amostra comunitária de 1220 homens e mulheres Portugueses completou o questionário com 40 itens. Realizou-se uma análise fatorial exploratória e confirmatória, bem como estatística comparativa para amostras independentes, através do software IBM SPSS Statistics e AMOS (ambos v. 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il., USA). A estrutura final com 24 itens repartidos por quatro fatores demonstrou, no geral, boas propriedades psicométricas (em termos de validade fatorial, consistência interna e sensibilidade) e validade convergente e discriminante questionável. O teste-t para amostras independentes identificou diferenças de género relativamente à frequência de fantasias sexuais. Esta investigação proporciona uma versão validada do Questionário de Fantasias Sexuais de Wilson, em Português. No que concerne às diferenças de género nas fantasias, apresenta também resultados consistentes e outros distintos comparativamente à literatura existente. São necessários mais estudos para se confirmar esta estrutura noutras amostras (e.g., clínicas e forenses).

Palavras-chave: diferenças de género, fantasias sexuais, questionário de fantasias sexuais de wilson, validação

Sexual fantasies can be defined as mental images that are sexually stimulating or erotic for an individual (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995). They can involve past experiences, anticipation for future sexual activities, desires or dreams, and there may not necessarily be an interest in its materialization. Research has shown that the fantasy's content is highly dependent on what a person reads, sees, listens and experiences directly (Malamuth, 1981), and it can also vary based on one's personality (Carlstedt, Bood, & Norlander, 2011). Leitenberg and Henning (1995) in their literature review found four common types of fantasies, across several studies, for both men and women: (a) intimate sexual imagery with known or imaginary lovers; (b) fantasies involving sexual prowess and seduction (including multiple partners); (c) scenes of an exploratory nature (different settings, positions, practices, questionable partners, etc.); and (d) submission/dominance acts that may involve sadomasochistic imagery.

Despite these major types of fantasies being common to both men and women, several studies have found gender differences in frequency and content (e.g., Crépault & Couture, 1980; Ellis & Symons, 1990; Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Wilson & Lang, 1981): men usually show more sexual fantasies than women, its contents being characterized as active (i.e., they imagine doing something to their partner), impersonal (i.e., multiple partners), and directed towards domination; meanwhile, women usually present more passive fantasies (i.e., they imagine something being done to done by their partners), favor intimate/romantic contents, and present more submission fantasies.

One of the more common measures used to assess sexual fantasies is the Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (SFQ; Wilson, 1988, 2010). It provides a method for assessing sexual fantasies, preferences and experiences in a quantified, standardized form. The SFQ has been used in community (e.g., Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Plaud & Bigwood, 1997; Sierra, Ortega, & Zubeidat, 2006), clinical (e.g., Vilar et al., 2016) and forensic samples (e.g., Baumgartner, Scalora, & Huss, 2002; Seifert, Boulas, Huss, & Scalora, 2017). Wilson (1988) used the principal components analysis with varimax rotation to obtain four primary factors: exploratory (e.g., group sex, promiscuity, mate-swapping), intimate (e.g., kissing passionately, oral sex, masturbating a partner), impersonal (e.g., sex with strangers, watching others, fetishism, looking at obscene pictures), and sadomasochistic (e.g., whipping and spanking, being forced to have sex). There is also a total fantasy score, calculated by summing all items, which provides a good measure of overall sex drive/ “libido” (Wilson, 1988, 2010).

The structure of the SFQ has been replicated in other cross-cultural studies. Plaud and Bigwood (1997), using a sample of 116 male North-American students, extracted four factors that accounted for 45% of the total variance. Although their analysis was consistent with the original model structure, the items saturated somewhat differently across the four factors. Iwawaki and Wilson (1983), in a sample of 60 male and 71 female Japanese students aged 18-20, also extracted a four-factor structure, similar but not alike to the original one. The four factors were exploratory, intimate, sophistication (with items from the intimate and impersonal scales) and nymphomania (with items like “sex with someone much older” and “taking someone's clothes off”). Sierra, Ortega, Martín-Ortiz and Vera-Villarroel (2004), using a sample of 370 female and 90 male Spanish students, extracted four factors that explained 45% of the total variance, but only partially supported the original structure, as two of the factors (impersonal and sadomasochistic) were identified as problematic. Furthermore, Sierra et al., (2006) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of a Spanish version of the SFQ with a sample of 195 males and 315 females aged 13-36, and found that the best fit model was a four factor structure with 24 items. The authors also tested a model with the overall total fantasy score as a second-order factor, as suggested by Wilson (1988, 2010), and found that using this score was not appropriate, claiming that it tended to reduce perceptible differences between individuals.

The main purpose of this study is to validate a Portuguese version of the SFQ by testing the factor structure to the current sample. We also tested the hypothesis that there would be gender differences regarding sexual fantasies in the Portuguese sample.

METHOD

Participants

The sample consisted of 1220 participants, between the ages of 18 and 64 (M=26.03; Sd=7.54). Of those, 43.6% were males (n=532) and 56.4% were females (n=687). The majority (50.5%, n=596) were students; 25.3% (n=299) were executives or specialists of intellectual and scientific professions (e.g., teachers, health, law and finance professionals); 20.8% (n=245) were intermediate level technicians, administrative personnel, security and armed forces professionals; lastly, 3.4% (n=40) were either agricultural or construction workers, or were unemployed. Out of all of these, 37% (n=448) were in a relationship at the time of the assessment.

The SFQ was previously translated into Portuguese and later retroverted into English by a bilingual third researcher. Pre-tests were applied to 10 people beforehand to check for inconsistencies. The SFQ was then administered online on a community Portuguese sample, with the link being shared through social media (e.g., Facebook, blogs) and university contacts. Informed consent was given. The subjects' participation was voluntary and anonymous and they did not receive any compensation for their participation.

Measure

The Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (SFQ) consists of 40 items, 10 for each of the four subscales (Exploratory, Intimate, Impersonal and Sadomasochistic). For each fantasy, participants give their responses on a five-point Lickert-type scale ranging from 0 to 5 for frequency (that is ‘never', ‘seldom', ‘occasionally', ‘sometimes', ‘often', and ‘regularly'). A global fantasy score is calculated through the sum of all the items.

Statistical and psychometric analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis with the AMOS software (v. 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il., USA) was used to examine the fit of the original model. Because this model showed a poor fit to the current sample, we opted to perform an exploratory factor analysis to explore factor structure of the SFQ. This analysis was made using the IBM SPSS Statistics software (v. 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il., USA), by means of the principal components method and a varimax rotation. It was made in 50% of the sample, randomly selected. Afterwards, we performed another confirmatory factor analysis to test the adjustment of the model that resulted from the exploratory factor analysis, on the remaining 50% of the sample.

To assess both models we used several global fit indexes, including the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, and its p-value for H0: rmsea≤.05, as well as the 90% confidence interval), and the (M)Expected Cross-Validation Index (MECVI). Model fit was considered acceptable for χ2/df ratio values between 3 and 4, CFI and GFI values around .90, PCFI and PGFI values above .60, and RMSEA values below .10 (Marôco, 2014).

To analyse the local model fit we considered the standardized regression weights (λ) and the item's individual reliability. Items with regression weights below 0.5 indicate possible problems with the local model fit (Marôco, 2014). Model fit was accomplished based on the Modification Indexes (IM>11; p<0.001), calculated through Lagrange Multipliers (LM; Marôco, 2014).

Sensitivity was explored through the Mahalanobis squared distance (D2) for outliers and the variables' normality was assessed through the skewness (Sk) and the kurtosis (Ku) uni- and multivariate coefficients. Sk and Ku values are expected to be below 3 and 7 respectively (Marôco, 2014). Reliability was analyzed using Cronbachs' α for each dimension and for the overall total fantasy score. Values above .70 indicate good reliability (Marôco, 2014).

Convergent validity was estimated through average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). Adequate values should be equal or higher than .50 and .70, respectively. Discriminant validity was explored by comparing the squared correlation of interfactors with the AVE of each individual factor. In order to have discriminant validity, the association between factors should be smaller than the individual AVE (Marôco, 2014).

Finally, to explore if there were significant differences between men and women, regarding the sex fantasy factors and the total fantasy score, we conducted an independent samples t-test. Normality assumptions were met for all variables and equal variances were assumed for all, except for the total fantasy score. For this analysis we used the better fit model on the whole sample.

RESULTS

Confirmatory factor analysis on the original model

The original model presented a poor adjustment to the data in the sample (χ2/df = 9.64; CFI=.63; GFI=.75; RMSEA=.08, p=.000, 90% confidence interval [CI] .082-.086; MECVI=5.95). There were six items (13, 20, 21, 23, 26 and 28) with sensitivity problems (i.e., Sk > 3; Ku > 7). There were also 12 items (3, 9, 13, 14, 19, 20, 23, 26, 28, 30, 35 and 37) with standardized regression weights (λ) ≤ .4. After first removing all six items with sensitivity issues and later the rest of the six items with λ ≤ 0.4 (item 30 was not removed since its λ was now = 0.5), the model still presented a poor adjustment (χ2/df=10.07; CFI=.75; GFI=.81; RMSEA=.09, p<0.001, 90% CI .084-.089; MECVI=2.95). There were also several correlations between residuals and latent variables, which indicated that the items were not saturating on the original factors.

Exploratory factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was performed on 50% of the randomly selected data from the total sample. Factors extracted were those with an eigenvalue greater than 1, identified by the scree plot, and theory-supported. The best fit solution was a five-factor structure, excluding 10 items (1, 8, 13, 19, 23, 26, 28, 29, 30 and 35) from the original questionnaire. These items were excluded because they presented poor association with the factor to which they were predictably associated in this analysis. Of note, the majority (5) of these items were formally from the impersonal subscale of the SFQ.

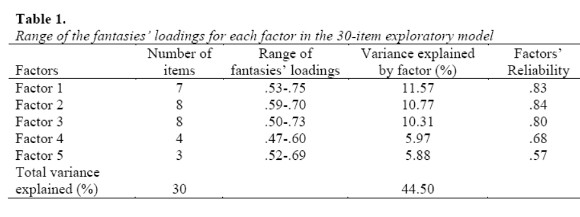

The sampling adequacy was confirmed by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO = .865) and the total variance explained by this five-factor structure was 44.5%. Table 1 presents the range of loadings of all fantasies that compose each one of the five factors, as well as the factors' reliability.

Despite the acceptable factor loadings of Factor 5, we opted to remove it from further analysis as it presented poor reliability and two of the items (20 and 21) showed sensitivity problems (i.e., Sk > 3; Ku > 7).

>Confirmatory factor analysis on the new model

The new model with 27 items presented a slightly better adjustment than the original, but was still a poor fit (χ2/df=5.19; CFI=.78; GFI=.82; RMSEA=.08, p =.000, 90% CI .078-.086; MECVI=2.85).

To better adjust the new model, three items (9, 12 and 39) were subsequently removed as they had standardized regression weights (λ) < 0.5 and did not fit, theoretically, with the factors to which they loaded in the exploratory factor analysis. Two of those items were also formally from the impersonal subscale of the SFQ.

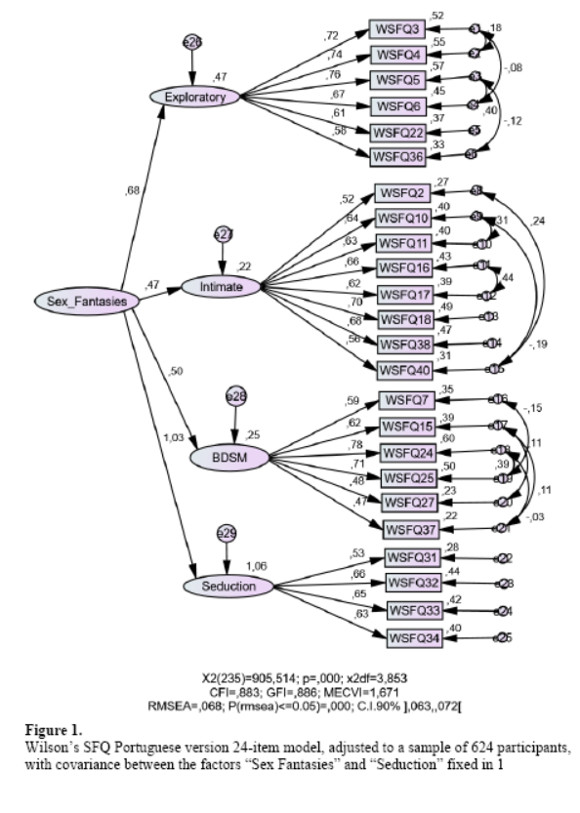

After covariances between errors were drawn, the model fit was good (χ2/df=3.53; CFI=.90; GFI=.90; RMSEA=.06, p=.000, 90% CI 0.59-.069; MECVI=1.55). We then decided to add a second-order factor for the overall total fantasy score. The new model showed a slightly worse adjustment, but it was still acceptable (χ2/df=3.85; CFI=.88; GFI=.89; RMSEA=.07, p=.000, 90% CI .063-.072; MECVI=1.67). Figure 1 presents the final model, including the standardized regression weights and individual reliability of the 24 items.

The 24-item, four-factor model that resulted from the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis had items that loaded in different factors than the original questionnaire. The first factor was still overall comprised of exploratory fantasies, but had two items each from the previous intimate and impersonal subscales, that fit with the theme of experimenting with different partners. The second one was still the intimate scale. The third factor also mainly consisted of items from the original sadomasochistic factor, but had one item from the previous impersonal scale that was suitable to the BDSM (Bondage/Discipline, Dominance/submission, and Sadism/Masochism) theme. We opted to name this factor as BDSM, as this name provided a broader fit for the overall range of fantasies obtained. The fourth factor mainly encompassed fantasies about being seduced or seducing someone and as such was named seduction. This last factor includes one item from the original impersonal and three others from the original exploratory scales.

Wilson's SFQ Portuguese version 24-item model, adjusted to a sample of 624 participants, with covariance between the factors “Sex Fantasies” and “Seduction” fixed in 1

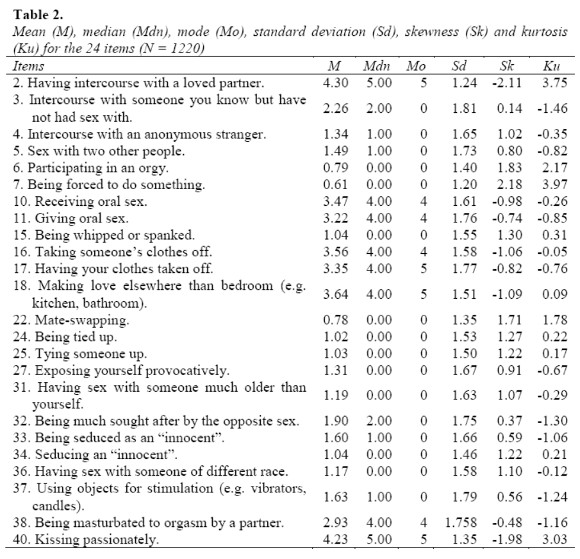

Sensitivity and reliability. To address sensitivity, we explored the mean, median, mode and standard deviation, as well as the skewness and kurtosis values for the 24 items, as shown in Table 2.

All factors presented good internal consistency (αexploratory=.84; αintimate=.85; αBDSM=.78; αseduction=.71), as well as the total fantasy score (α=.87).

Convergent and discriminant validity. The factors assumed poor average variance extracted (AVEexploratory=.47; AVEintimate=.40; AVEBDSM=.38; AVEseduction=.39), but great composite reliability (CRexploratory=.84; CRintimate=.84; CRBDSM=.78; CRseduction=.71).

Of the possible comparisons for the 12 paired-factors, for the existing four first-order factors, only half presented good discriminant validity. The six exceptions with low discriminant validity were the following pairs: exploratory and seduction; intimate and seduction; and BDSM and seduction.

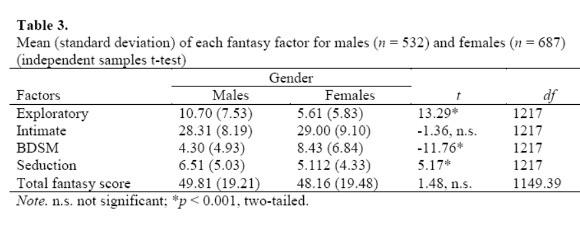

Gender differences in sex fantasies. Finally, to analyse if there were differences in sex fantasies based on gender, we conducted an independent samples t-test for the four factors and for the overall total fantasy score (2nd order factor). As evidenced in Table 3, there were significant differences between men and women for most fantasies.

DISCUSSION

The Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire is a self-report measure that assesses the frequency of a person's sexual fantasies and experiences. The original structure distributed the 40 items through four factors: exploratory, intimate, impersonal and sadomasochistic. This model showed poor adjustment to our sample and indicated that several items saturated in different factors.

The exploratory factor analysis we conducted on 50% of the sample, randomly selected, showed a five factor model that explained 45% of the total variance, which is similar to previous research (Plaud & Bigwood, 1997; Sierra et al., 2004). After removing the fifth factor, due to sensitivity problems with its items (“hurting a partner” and “being hurt by a partner”), the best fit model supported a four-factor structure, equal to other cross-cultural studies (Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Plaud & Bigwood, 1997; Sierra et al., 2004; Sierra et al., 2006).

The best fit model of this Portuguese version of the SFQ encompassed 24 items and showed good reliability. Interestingly, the Spanish version of the SFQ (Sierra et al., 2006) also consisted of 24 items, after model refinement through confirmatory factor analysis. Unlike this Spanish study, that encountered problems with the total fantasy score serving as a second-order factor, our model was still acceptable with this addition. The author (Wilson, 1988, 2010) maintains that this factor provides a good measure of overall sex drive/ “libido”.

In spite of the common four-factor structure, the items distributed somewhat disparately from the original, which has also occurred in other studies (Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Plaud & Bigwood, 1997).

The exploratory scale suffered some changes. Three of the items saturated in a separate factor. Three others were removed (“homosexual activity”, “having incestuous sexual relations”, and “being promiscuous”), because they did not load anywhere else, showing no clear association with the other fantasies. On the other hand, the items “intercourse with someone you know but have not had sex with” (previously from the intimate scale) and “intercourse with an anonymous stranger” (from the impersonal scale) showed a clear association with the rest of the exploratory scale. The overall resulting theme of this factor was about fantasies concerning sexual practices with other people not your partner.

The intimate scale remained largely the same, minus the item that saturated in the exploratory factor and the removal of the one that refers to outdoor love, as it did not load elsewhere. The more aggressive items in the original sadomasochistic scale (“forcing someone to do something”, “hurting a partner” and “being hurt by a partner”) showed adjustment problems to our sample and had to be removed. Possibly because these fantasies are not commonly reported in a community sample. The item “transvestism” was also removed, as it did not saturate in any of the factors. From a theory perspective, it makes sense that it did not fit in the original sadomasochistic scale, as it is a very specific type of paraphilia. Without these items, and with the added “using objects for stimulation” (from the original impersonal scale), the majority of the fantasies in this factor fit under the overall BDSM (Bondage/Discipline, Dominance/submission, and Sadism/Masochism) theme, and we renamed it as such.

We found a different fourth factor than the original model, with three items that were previously categorized as exploratory and one other that was from the impersonal scale. A common theme among these four fantasies is seduction of others or the self, and we opted to name it seduction. Of note, from the four types of most common fantasies found by Leitenberg and Henning (1995), sexual prowess and seduction was one of them. Besides, Iwawaki and Wilson (1983) found a similar (but not exactly alike) factor that revolved around the seduction topic, and was separate from the exploratory scale, but decided to name it nymphomania.

The original impersonal scale was inexistent in our sample, with only three items saturating in the remaining extracted factors. That may be because most of the others actually resemble different types of paraphilias (e.g., zoophilia in the case of “sex with an animal.”; voyeurism in the “watching others have sex”; fetishism in the “being excited by material or clothing”; and urophilia in the “being aroused by watching someone urinate”), with no clear theoretical association between them.

Finally, we tested our sample for gender differences with our version of the SFQ. Unlike other studies that have found that men present overall more fantasies than women, and specifically less intimate ones (Ellis & Symons, 1990; Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Wilson & Lang, 1981), we did not find any differences in our sample. Furthermore, as the majority of our BDSM items were of a passive nature, it comes as no surprise that women had more of this kind of fantasies (Iwawaki & Wilson, 1983; Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Wilson & Lang, 1981). Regarding our seduction scale, which has not been used in other research with this measure, we found that men presented more of this type of fantasies.

Although we found good factorial validity for this Portuguese version of the SFQ, it showed mixed results in regards to its convergent and discriminant validity. The seduction scale had problems discriminating from the other factors, indicating a strong association with them. More studies are needed to confirm this structure with other samples (e.g., clinical and forensic) and in other contexts (e.g., in person, as opposed to the Internet).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no support to report.

REFERENCES

Baumgartner, J. V., Scalora, M. K., & Huss, M. T. (2002). Assessment of the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire among child molesters and nonsexual forensic offenders. Sex Abuse, 14(1), 19-30. doi: 10.1177/107906320201400102 [ Links ]

Carlstedt, M., Bood, S. A., & Norlander, T. (2011). The affective personality and its relation to sexual fantasies in regard to the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire. Psychology, 2(8), 792-796. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.28121 [ Links ]

Crépault, C., & Couture, M. (1980). Men's erotic fantasies. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 9(6), 565-581. doi: 10.1007/BF01542159 [ Links ]

Ellis, B. J., & Symons, D. (1990). Sex differences in sexual fantasy: An evolutionary psychological approach. Journal of Sex Research, 27(4), 527–555. doi: 10.1080/00224499009551579 [ Links ]

Iwawaki, S., & Wilson, G. D. (1983) Sex fantasies in Japan. Personality and Individual Differences, 4(5), 543-545. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(83)90086-7 [ Links ]

Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 469-496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.469 [ Links ]

Malamuth, N. M. (1981). Rape fantasies as a function of exposure to violent sexual stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 10(1), 33-47. doi:10.1007/BF01542673 [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações (2.ª Edição). Lisboa, Portugal: Report Number. [ Links ]

Plaud, J. J., & Bigwood, S. J. (1997). A multivariate analysis of the sexual fantasy themes of college men. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 23(3), 221–230. [ Links ] doi: 10.1080/00926239708403927

Seifert, K., Boulas, J., Huss, M. T., & Scalora, M. J. (2017). Response bias on self-report measures of sexual fantasies among sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(3), 269-281. [ Links ] doi:10.1177/0306624X15593748

Sierra, J. C., Ortega, V., & Zubeidat, I. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis of a Spanish version of the Sex Fantasy Questionnaire: Assessing gender differences. Journal of Marital and Sexual Therapy, 32, 137–159. [ Links ] doi: 10.1080/00926230500442318

Sierra, J. C., Ortega, V., Martín-Ortiz, J. D., & Vera-Villaroel, P. (2004). Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario De Wilson De Fantasías Sexuales [Psychometric properties of Wilson's Sex Fantasy Questionnaire]. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 21(1), 37-50.

Vilar, G. C., Concepción, E., Galynker, I., Tanis, T., Ardalan, F., Yaseen, Z., & Cohen, L. J. (2016). Assessment of sexual fantasies in psychiatric inpatients with mood and psychotic disorders and comorbid personality disorder traits. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(2), 262-269. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.020 [ Links ]

Wilson, G. D. (1988). Measurement of sex fantasy. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 3(1), 45-55.Doi 02674658808407692 [ Links ]

Wilson, G. D. (2010). The Sex Fantasy Questionnaire: An update. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 25(1), 1-5. doi: 10.1080/14681990903505799 [ Links ]

Wilson, G. D., & Lang, R. J. (1981). Sex differences in sexual fantasy patterns. Personality and Individual Differences, 2(4), 343-346. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(81)90093-3 [ Links ]

Endereço para Correspondência

Rua Jardim do Tabaco, nº34, 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal. Telf.: +351 218811700. e-mail: mariana.amaral.saramago@gmail.com

Recebido em 06 de Janeiro de 2017 / Aceite em 09 de Outubro de 2017