Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.19 no.2 Lisboa ago. 2018

https://doi.org/10.15309/18psd190201

Posttraumatic growth in adult cancer patients: an updated systematic review

Crescimento pós-traumático em adultos com cancro: uma revisão sistemática atualizada

Catarina Ramos 1,2, Filipa Pimenta1,2, Ivone Patrão2,3, Margarida Costa 3, Ana Isabel Santos2, Tânia Rudnicki4, Isabel Leal 1,2

1WJCR-William James Center for Research;

2ISPA - Instituto Universitário, Lisboa; Rua Jardim do Tabaco, nº 34. 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal, aramos@ispa.pt, filipa_pimenta@ispa.pt, Ivone_patrao@ispa.pt, ileal@ispa.pt

3Applied psychology research center capabilities and Inclusion (APPsyCl);

4Capes Foundation Ministry of Education Of Brazil-Brasília/DF - Brazil; Centro Universitário da Serra Gaúcha -FSG - Caxias do Sul/RS - Brazil.

ABSTRACT

The current systematic review is an updated analysis of studies with adult cancer patients, regarding factors associated with posttraumatic growth (PTG), which is defined as perceived positive changes after traumatic event, such as cancer. A systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA Statement guidelines. Seven electronic databases were searched. Quantitative studies with or without psychosocial group intervention that assessed PTG or similar construct (benefit finding [BF], positive life changes, stress-related growth, growth) as main outcome were included. The initial systematic search yielded 659 papers, published between 2006 and 2015. From those, 81 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria: 73 studies without intervention and 8 entailing an intervention program. The results suggested that socio-demographic (e.g. age, educational level, household income), clinical (e.g. stage of cancer), cognitive (e.g. intrusiveness, challenge to core beliefs), coping-related (e.g. positive reframing, religious coping) and other psychosocial variables (e.g. social support, optimism, spirituality) are positively associated with PTG. BF is associated with gender, marital status, cancer stage, both cancer and treatment type, positive active coping, positive reappraisal, social support and optimism. Psychosocial group interventions with cancer patients show significant effect on the increase of growth reported (PTG or BF). As conclusion, Growth following a cancer experience is an effect of several variables which might be targeted and promoted in the context of multidisciplinary teams, in hospital and clinical settings. Group interventions are a favorable context to the development of PTG after cancer, but interventions that assess PTG as primary outcome are still needed to evaluate the effect of group on PTG' facilitation.

Keywords:growth, posttraumatic growth, benefit finding, cancer

RESUMO

A presente revisão sistemática é uma análise atualizada de estudos com adultos com cancro, em relação aos fatores associados ao crescimento pós-traumático (CPT), o qual é definido como mudanças positivas percebidas após um acontecimento traumático como cancro. Esta revisão sistemática foi conduzida de acordo com as diretrizes da PRISMA. A pesquisa foi efetuada utilizando sete base de dados e os seguintes critérios de inclusão: estudos quantitativos com ou sem intervenção em grupo que avaliaram o CPT, ou constructo semelhante (benefícios percebidos [BP], mudanças de vida positivas, crescimento relacionado ao stress, crescimento), como resultado principal foram incluídos. De 659 artigos, publicados entre 2006 e 2015, 81 estudos preencheram os critérios de inclusão: 73 estudos sem intervenção e 8 estudos com programa de intervenção. Os resultados indicam que variáveis sócio-demográficas (e.g., idade, educação, estatuto sócio-económico), clínicas (por exemplo, estadio do cancro), cognitivas (e.g., pensamentos intrusivos, mudança de crenças centrais), relacionadas com o coping (e.g., reestruturação positiva, coping religioso) e outras variáveis psicossociais (e.g., apoio social, otimismo, espiritualidade) estão positivamente associadas ao CPT. BP está associado ao género, ao estado civil, ao estadio do cancro, ao tipo de cancro, ao tipo de tratamento, coaching ativo positivo, reavaliação positiva, apoio social e otimismo. As intervenções do grupo psicossocial com pacientes com câncer apresentam efeito significativo no aumento do relatório de crescimento (CPT ou BP). Como conclusão, o crescimento após uma experiência de cancro é um efeito de várias variáveis que podem ser direcionadas e promovidas por equipas multidisciplinares em contextos hospitalares e clínicos. As intervenções em grupo são um contexto favorável ao desenvolvimento de CPT após o câncer, mas as intervenções que avaliam o CPT como resultado primário ainda são necessárias para avaliar o efeito do grupo na facilitação do CPT.

Palavras-chave: crescimento, crescimento pós-traumático, benefícios percebidos, cancro.

During the last decades there has been an increase in the number of cancer diagnoses. According to World Health Organization (WHO, 2015), about 14 million new cases emerge every year, of which 8.2 million ultimately die. Having cancer represents an experience associated with multiple stressors. Due to a sudden and unexpected diagnosis, cancer can be a traumatic experience, which induces strong emotional responses, such as stress, anxiety, depression or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Barskova & Oesterreich, 2009).

Although the majority of studies have been focusing on the negative outcomes of cancer experience, there has been recent empirical studies showing a perception of positive changes after cancer. Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) has been recognized in the literature as the mainstream concept to define these positive changes, which accrue from the subject's attempts to cope with trauma (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; 2004).

Such as PTG, benefit finding (BF) is also another mainstream concept to define positive changes after trauma; however, they appear to be different constructs. According to Mols and colleagues (2009), BF develops immediately after the traumatic experience, whether PTG develops through time, since it is a product of successive rumination and cognitive restructuration. As a consequence, BF appears to be more superficial and fleeting, unlike PTG that changes the individual way of living and perceiving oneself (Harding et al., 2014). Other authors suggested the same idea, emphasizing that PTG originates self-related changes, unlike BF, which causes life style and behavioral changes (Koutroli et al., 2012; Lelorain et al., 2010). Being a complex and dynamic process, PTG occurs in interaction with multiple factors, which influence the subjective perception of the traumatic event (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004). The PTG model (Tedeschi & Calhoun 1996; 2004) lists several variables as facilitators to the development of PTG, such as environmental characteristics (e.g. social support), event characteristics (e.g. duration), or coping strategies (e.g. problem-focused coping). Several empirical studies conducted with cancer patients are in line with this model, suggesting that PTG is predicted by the following variables: sociodemographic (e.g. age, educational level, income, marital status) (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Cordova et al., 2007; Danhauer et al., 2013a; Llewellyn et al., 2013); clinical (e.g. stage, type of cancer, type of treatment) (Danhauer et al., 2013a; Thornton et al., 2012); psychological (e.g. anxiety, depression, PTSD) (Cordova et al., 2007; Thornton et al., 2012); physical (e.g. cortisol, immune function, physical exercise) (Diaz et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014); cognitive (e.g. coping, rumination, core beliefs) (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Danhauer et al., 2013b; Llewellyn et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2012); social (e.g. social support, emotional disclosure) (Danhauer et al., 2013a; Llewellyn et al., 2013); and others such as optimism (Llewellyn et al., 2013), spirituality (Danhauer et al., 2013a), and religiosity (Thuné-Boyle et al., 2011).

Even though there has been empirical evidence about which factors are PTG' predictors in cancer patients, inconsistencies remain relatively to the predictive value of some factors towards PTG, such as PTSD symptoms for example (Cordova et al., 2007; Morrill et al., 2008). In an effort to shed light on this construct, some systematic reviews have been conducted (Casellas-Grau, Font, & Vives, 2014; Casellas‐Grau, Ochoa, & Ruini, 2017; Harding et al., 2014; Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Koutroli et al., 2012; Shand et al., 2015; Stanton et al., 2006). However, these inconsistencies are still to be clarified in the light of current empirical and intervention studies.

Hence, there is still a need to further systematize the available results in order to offer both clinicians and researchers a better understanding about the predictors of the development of personal growth in the aftermath of cancer, and new evidences of relationships between personal growth after cancer and psychological and physical variables that, until now, were not covered by past studies. Also, we intend to explore some aspects neglected by previous systematic reviews, such as: a) the inclusion of studies with similar concepts, for example BF, stress-related growth, and positive life changes, since the independence of these concepts and PTG has not been fully demonstrated (Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Koutroli et al., 2012); b) the inclusion of different types of cancer, since the previous reviews only included a specific type of cancer such as breast (Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Koutroli et al., 2012) or head and neck cancer (Harding et al., 2014); c) the inclusion of intervention studies in addition to empirical studies (Casellas-Grau et al., 2014; 2017; Harding et al., 2014; Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Shand et al., 2015); and d) the assessment of risk of bias of the empirical articles (Kolokotroni et al., 2014; Koutroli et al., 2012).

With the purpose to fill these gaps, this updated review will include studies with both PTG and BF (or similar constructs defining the perceived positive changes after a traumatic event) and will assess the quality of the included studies. The objectives of the current systematic review are as follows: to analyze the presence of growth in patients with the diagnosis of cancer; to explore the relationship between growth and clinical, sociodemographic, and psychosocial variables; to discuss the perception about positive changes during the course of different types of cancer; and to contribute to enlarge the scientific and clinical knowledge about PTG in cancer patients.

METHOD

This systematic review was developed according to APA's Meta-Analysis Reporting Method (APA Publications and Communications Board Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards, 2008) and Preferred Reporting Itens for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009); and had the review record CRD420103012 on the PROSPERO register.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible studies were original, published, and empirical (with or without intervention) studies, that had assessed growth in cancer patients and had examined the relationship between growth and at least one socio-demographic, psychological or social variable. Cross-sectional or longitudinal studies were eligible for inclusion as well as quantitative studies, randomized controlled trials (studies with an intervention) and comparative studies. English, French, Spanish and Portuguese papers were included. Additional inclusion criteria were the following: In primary studies, positive changes were assessed through the construct of PTG, BF, positive life changes, adversarial growth, or stress-related growth; Growth was evaluated with a valid measure (e.g. Posttraumatic Growth Inventory - original or short form; Benefit Finding Scale); PTG (or similar construct) was defined as primary outcome in empirical studies and as primary or secondary outcome in intervention studies; Study participants were adult patients who had been diagnosed with any type of cancer (e.g. breast, prostate, colon, etc.), who were in phase of diagnosis, treatment, or surveillance. Randomized controlled trials that included any type of psychosocial intervention, conducted by a health professional (e.g. psychologist, nurse, physiotherapist); Individual or group interventions, targeting patients (who adhere individually or with a partner/spouse or other family member) were also included.

Conversely, the exclusion criteria were the following: qualitative studies; mixed methods; meta-analysis, systematic and literature reviews; unpublished researches; book chapters, commentaries and editorials, thesis, or abstracts from Congresses' presentations; studies free of intervention, that assessed PTG as a secondary outcome or as a mediator variable were excluded; However, since most interventions did not directly focus PTG's development, this systematic review included intervention studies which had PTG as a secondary outcome. Studies that measured PTG through open questions and not through valid measures (e.g. PTGI) and studies with interventions only with family members of a cancer patient were also not considered. Articles in which samples included cancer patients in addition to patients from other diseases were also not included in this systematic review. Exclusion criteria related to individual characteristics (e.g. gender or ethnicity) and cancer-related characteristics (e.g. stage, surgery, or metastasis) were not used.

It is important to note that, overlapping samples were found: when different papers reported separate results regarding the same sample or substantially overlapping samples, the distinct papers were assumed as one single study, counting as one entry (e.g. Ruini et al., 2013; 2014).

Search Strategy

Studies were identified by searching multiple literature databases related to health, medicine and psychology, such as MEDLINE, PsychArticles, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scielo, PePsic, and Web of Science. We restricted the search to studies published between January 2006 and May 2015, since the last systematic review with adult cancer patients had included studies up to the year 2005 (Stanton et al., 2006). The selection of studies for eligibility and data extraction were performed by five independent researchers and possible disagreements were discussed and solved between them.

To identify papers addressing growth and cancer the following search terms were used: posttraumatic growth; growth; benefit finding; positive life changes; stress-related growth; cancer; oncological disease; neoplasm; tumor; and carcinoma. In order to select the articles that met the inclusion criteria and to exclude the others that did not meet them, the titles and abstracts were examined. If necessary, and in order to clarify any information, the full papers were also examined.

In order to avoid source selection bias and to ensure an exhaustive and comprehensive search procedure, additional search strategies were applied such as searching of scientific journals which had published relevant articles in this area, analyzing the reference list of primary studies, and exploring other databases such as national library databases.

Search Results

The initial searches from the databases identified 659 potentially relevant studies. After the examination of the titles, abstracts and full articles, we excluded papers based on inclusion criteria mentioned above. Thus, a total of 578 studies were excluded because they were systematic reviews and/or meta-analysis, literature reviews, theoretical articles or commentaries (56); were chapters, books, or abstracts from presentations in conferences (141); were thesis or dissertations (55); used qualitative or mixed methodology (70); were study protocols (4); assessed psychometric properties or validated a measure that assessed PTG or similar construct (22); were non-randomized trials or non-experimental studies (6); used only caregivers or family members of patients, as sample (40); used samples consisted of children or adolescents that suffered from cancer (20); were papers written in languages other than the ones mentioned in the inclusion criteria (24); assessed only medical outcomes or PTG as a result of a medical procedure (27); did not measure PTG (or similar construct), PTG was not assessed as primary outcome or was assessed as a mediator variable (105); used open questions to measure PTG, did not use one of the main growth measures or used changed versions (without previous validation) of the measure (8). Figure 1 displays a flowchart of studies.

Quality Assessment

The final sample consists of 81 eligible studies and the general quality of each study was assessed using a 29-item check-list adapted from the Quality Assessment Tool - Cochrane's Handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011). Accordingly, the quality from each study was assessed by the evaluation of the following items: 1) introduction (e.g., background of the existing literature); 2) objectives (description of objectives and/or hypothesis of the study); 3) study design; 4) sampling process; 5) participants' recruitment; 6) sample size calculation; 7) inclusion and exclusion criteria; 8) data collection locals (name and/or other characteristics of data collection locals); 9) ethic committee' approval; 10) differences between groups (description of the identification and/or resolution of the differences between groups); 11) identification of the existent conditions/groups - e.g. control vs. treatment; 12) randomization method description; 13) description of the intervention for the experimental group; 14) description of the intervention for the control/alternative group; 15) study' costs; 16) assessments (description of how, who and where were carried out); 17) blind assessment; 18) drop-outs (numbers and/or reasons for drop-outs); 19) socio-demographic characteristics; 20) cancer-related characteristics; 21) measures (description and/or psychometric properties); 22) statistical analysis; 23) results (detailed and adequate description of the results); 24) discussion (literature-based discussion of the results); 25) generalization (or not) of the results; 26) limitations; 27) registration of the intervention program; 28) sources of funding; and 29) conflict of interests. It is important to note that the items 12, 13, 14, and 27 were exclusive to studies that encompassed a group intervention.

The majority of the 29 items was scored through a scale consisted of three points from 0 to 2: 0 (not done / or not reported), 1 (done but unclear and /or reported to some extend), 2 (adequately done and/ or adequately reported) (Higgins & Green, 2011). However, five items were scored from 0 to 3, since they accumulated more than one aspect needed to be assessed in the context of quality evaluation; an example of this was the item that assessed the quality of the measures' report (0 - not done; 1- done but not clear; 2- reported without psychometric characteristics; 3- reported, including psychometric characteristics).

Five researchers independently assessed the quality of the included studies. The inter-rater agreement between pairs of two researchers was calculated on 65 papers (80%) through the Cohen's Kappa and the averages were good, as following: .966; .963; .943; .898; .801. Disagreements in quality assessment were resolved by consensus between pairs of two researchers. Remain divergences were clarified by the researcher CR.

A summary of the quality assessment is presented in table 1 for cross-sectional studies, and in table 2, for longitudinal and intervention studies.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

Data Extraction

Both study selection procedure and data extraction were carried out by the five independent researchers. Discrepancies related to the data extraction were discussed between the five researchers in consensus meetings.

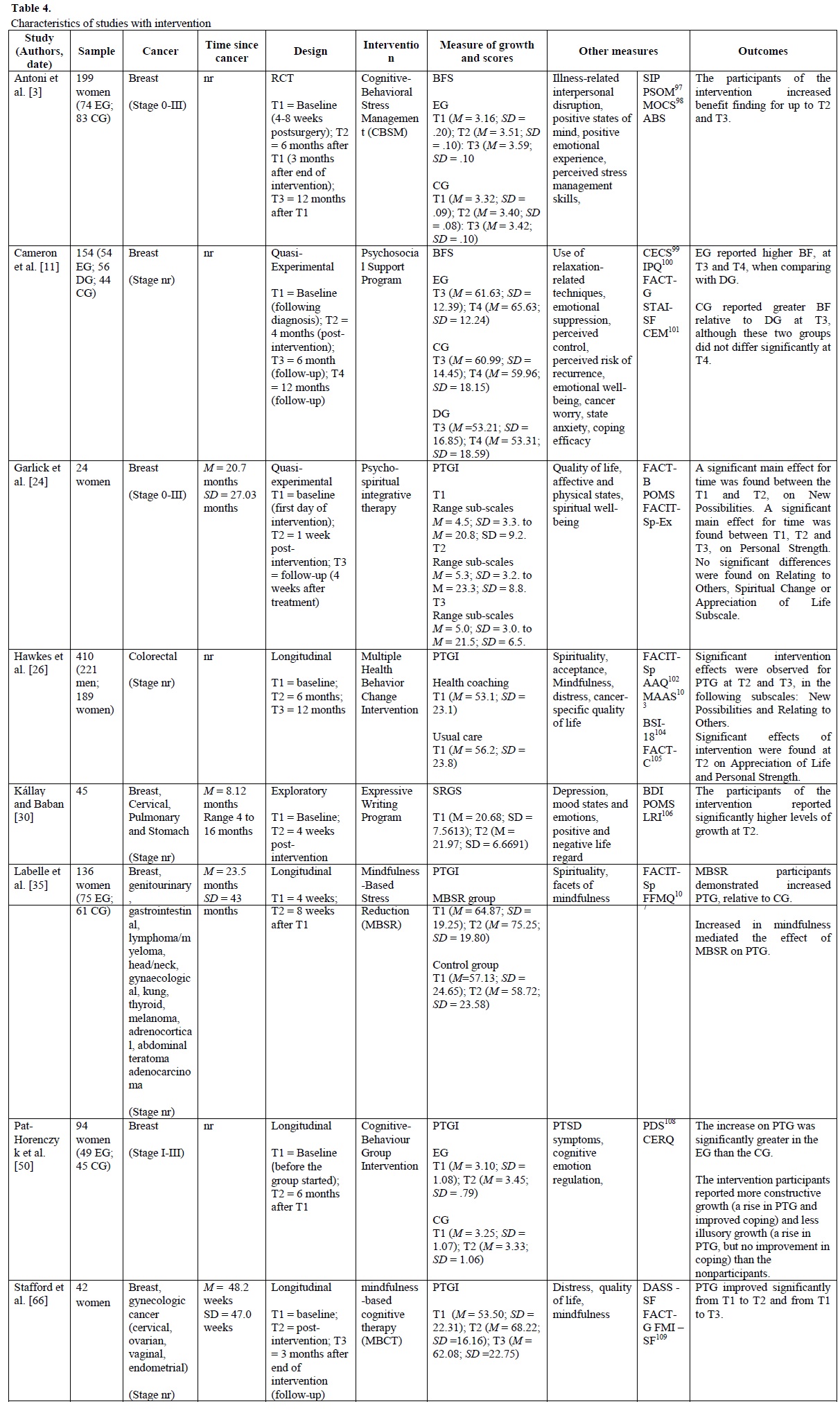

Table 3 in the Supplementary Material summarizes the main characteristics of the 73 non-intervention studies: a) study (authors, date); b) number of participants; c) cancer type; d) cancer stage; e) time since diagnosis; f) design; g) measure of growth (i.e., instrument used to assess growth and mean and standard deviation of growth); h) other variables (namely, additional variables assessed and respective measures used to evaluate each of them); i) main outcomes (factors associated with or predictors of growth). These characteristics were selected in order to advance the understanding of the relations between growth and sociodemographic, psychological and social variables among adult patients diagnosed with cancer. The intervention studies were characterized regarding the same features; additionally the type of the intervention was included, as shown in table 4 in the Supplementary Material.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

RESULTS

In total, 81 studies (8 entailing an intervention) were included evidencing an association of socio-demographic, health and treatment, and lifestyle characteristics with growth. Moreover, psychosocial variables (such as anxiety, depression, illness intrusiveness, positive reframing, etc.) were also found to be associated. Furthermore, studies with and without intervention will be reported separately, as well as studies that assessed PTG or BF.

Empirical Studies Without Intervention

The main characteristics and outcomes of the 73 studies are shown in table. It is important to note that the reported results focus on the main outcomes outlined by the authors and considering the more complex and comprehensive level of analysis; that is, if only univariate analysis was done, the results will mirror this information; however, if after a univariate analysis the study presents a multivariate analysis, the latter will be the only one being reported.

Socio-demographic factors associated with PTG.

The majority of studies found a significant association between age and PTG (e.g. Bellizzi et al., 2010; Brix et al., 2013; Cormio et al., 2015; Cordova et al., 2007; Danhauer et al., 2015; Danhauer et al., 2013b; Heidarzadeh et al., 2014; Kent et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2007; Mystakidou et al., 2008; Rahmani et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014; Tanyi et al., 2015); however, other studies found an absence of correlation between both variables (Baník & Gajdoová, 2014; Ho et al., 2011; Svetina & Nastran, 2012). According to the findings from most studies, younger age is correlated with higher PTG (e.g. Cordova et al., 2007; Cormio et al., 2015; Danhauer et al., 2013b). Given that only few studies evaluated the relationship between PTG and gender and the results were not unanimous - some report an association with female gender (Smith et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015) while others report an absence of association (Cormio et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2011) - this relationship remains unclear.

A higher education level is also associated with higher PTG according to most studies (e.g. Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Cordova et al., 2007; Danhauer et al., 2013a; Heidarzadeh et al., 2014; Rahmani et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2014); yet, a few number did not find a significant association (Cohen & Numa, 2011; Ho et al., 2011; Mystakidou et al., 2008; Svetina & Nastran, 2012). In what regards race or ethnicity, most studies support that this variable is associated with growth (e.g. Danhauer et al., 2015; Kent et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2008; 2014). Although there is a lack of unanimity, there is strong evidence that being married (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Mystakidou et al., 2008; Ho et al., 2011); higher household income (Heidarzadeh et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014); and being unemployed (Bellizzi et al., 2010) are significantly correlated with PTG.

Cancer-related factors associated with PTG.

Regarding disease-related variables, stage of cancer at diagnosis (Bellizzi et al., 2010; Ho et al., 2011; Kent et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2008; 2014), and disease/trauma severity (Morris and Shakespeare-Finch, 2011a; Posluszny et al., 2011) were positively associated with PTG.

Otherwise, a number of studies failed to find any significant association between PTG and time since diagnosis (Cohen & Numa, 2011; Cordova et al., 2007; Cormio et al., 2015; Heidarzadeh et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Rahmani et al., 2012; Thombre et al., 2010); time since treatment (Cordova et al., 2007; Ho et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2007); type of treatment received (Baník & Gajdoová, 2014; Cormio et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2011); and type of surgery (Cohen & Numa, 2011; Silva et al., 2012; Thombre et al., 2010). Moreover, the effect of several clinical variables on PTG remains unclear, such as, type of cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonotherapy, comorbidities, presence/absence of metastasis and disease recurrence. Additionally, it is important to note that very few studies with metastatic cancer patients (a sample that is difficult to invite to participate) were found, which can compromise the consistency and the generalization of the results.

Physical factors associated with PTG.

In what regards physical variables, only one study had found a negative and significant correlation between PTG and cortisol slope, indicating an association between a healthier endocrine functioning and positive psychological changes (Diaz et al., 2014).

Psychosocial factors associated with PTG.

The major part of the studies showed a significant association with growth, particularly, with a higher perception of cancer as a life-threatening/traumatic event (Cordova et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2014) and higher perceived intensity/severity of cancer (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006) leads to positive changes (i.e. PTG). Cancer-related intrusions or intrusive rumination were associated with higher PTG (e.g. Danhauer et al., 2013a; 2015; Soo & Sherman, 2015; Thornton et al., 2012), which reinforces the positive association that has already been found in other studies (e.g. Cann et al., 2011).

Moreover, among mental health variables, the relationship between PTG and some factors remains unclear or inconsistent, such as depressive symptoms, distress, and PTSD symptoms, since a similar number of studies reported contrary results. Also, three studies failed to find any significant association between anxiety and PTG (Abdullah et al., 2015; Mystakidou et al., 2008; Salsman et al., 2009).

Several studies have examined the relations between growth and positive efforts or strategies to lead with a stressful traumatic event such as cancer. In fact, from the 25 studies that investigated PTG and coping, 12 of them showed that PTG is significantly associated with the following coping-related variables: positive active-adaptive coping (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Danhauer et al., 2013a; Danhauer et al., 2015; Lelorain et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2007; Scrignaro et al., 2011); prognosis' acceptance-coping (Tang et al., 2015); problem-focused coping (Büyükaşik-Çolak et al., 2012; Scrignaro et al., 2011) and emotional-focused coping (Büyükaşik-Çolak et al., 2012; Thornton et al., 2012). Among all coping-related variables, many studies showed a significant positive association with positive reframing/reappraisal and growth (Bussell & Naus, 2010; Cormio et al., 2015; Morris et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2011; Scrignaro et al., 2011; Thornton et al., 2012). This result is in accordance with findings from Shand and colleagues (2015). Additionally, five studies showed a positive association between religious coping and growth (Cormio et al., 2015; Lelorain et al., 2010; Rand et al., 2012; Schmidt et al., 2012). The only two studies that investigated the relationship between spirituality and growth, proved the initial hypothesis of positive correlation between both variables (Danhauer et al., 2013a; Smith et al., 2008)

PTG was significantly and positively associated with perceived social support (Bozo et al., 2009; Cohen & Numa, 2011; Danhauer et al., 2013a; Morris and Shakespeare-Finch, 2011b; Smith et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015; Tanrıverd et al., 2012). However, two studies failed to find a significant association (Cohen & Numa, 2011; Schmidt et al., 2012).

In recent years, and as confirmed by our results, growth has been positively associated with other positive/empowerment variables, such as happiness (Lelorain et al., 2010); satisfaction with life (Mols et al., 2009); hope (Ho et al., 2011); optimism (Bozo et al. 2009; Ho et al., 2011); openness to experience (Strack et al., 2010); and gratitude (Strack et al., 2010). Nevertheless, other two studies failed to find a relation between PTG and optimism (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006; Smith et al., 2008) and hope (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006).

Sociodemographic factors associated with BF.

Regarding sociodemographic features, studies failed to find significant correlations between BF and gender (Cavell et al., 2015; Harrington et al., 2008), employment status (Garland et al., 2013; Harrington et al., 2008) and marital status (Harrington et al., 2008). Alike studies with PTG, there are inconsistent findings regarding the association between BF and age and educational level.

Clinical factors associated with BF.

Most of the studies did not find a significant correlation between BF and time since diagnosis (Cavell et al., 2015); type of cancer (Garland et al., 2013); type of treatment (Harrington et al., 2008); and stage of cancer (Garland et al., 2013; Harrington et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2015). Though, Garland et al. (2013) and Mols et al. (2009) found significant associations between BF and time since diagnosis and stage of cancer at diagnosis, respectively.

Psychosocial factors associated with BF.

Concerning psychosocial factors the following variables were significant predictors of BF: positive active coping (Cavell et al., 2015; Kinsinger et al., 2006; Llewellyn et al., 2013); positive reappraisal (Harrington et al., 2008; Schroevers et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015); social support (Dunn et al., 2010; Kinsinger et al., 2006; Schultz & Mohamed, 2004); and optimism (Dunn et al., 2010; Harrington et al., 2008; Llewellyn et al., 2013). These results are in accordance with studies on PTG. Furthermore, Park et al. (2009) showed a significantly positive association between perceived benefits and religious coping, but not with religiousness. In addition, Thuné-Boyle and colleagues (2011) found that the relationship between BF and religious coping to achieve a life transformation was partially mediated by strength of faith.

Nevertheless, some studies did not find a significant correlation between BF and quality of life (Dunn et al., 2010; Kinsinger et al., 2006; Llewellyn et al., 2013), anxiety (Cavell et al., 2015; Dunn et al., 2010; Harrington et al., 2008; Llewellyn et al., 2013), and depression (Cavell et al., 2015; Harrington et al., 2008; Llewellyn et al., 2013).

Comparison between groups.

Some studies have made the comparison between patients with cancer and healthy controls regarding PTG. Most studies showed that women with breast cancer (Posluszny et al., 2011; Ruini et al., 2013; 2014; Martins da Silva et al., 2011) have higher PTG levels comparing with healthy counterparts. In contrast, a study from Brix et al. (2013) found no significant differences in PTG reported by women with breast cancer and healthy women.

Other comparisons were made between groups. As an example, in a study with women with breast cancer, Cohen and Numa (2011) found that participants who were volunteers reported similarly high levels of PTG, in comparison with non-volunteers. Also, Caucasian American women with breast cancer displayed higher PTG than African American counterparts (Bellizzi et al., 2010).

PTG mediators.

Besides the direct effects of distinct variables on PTG model, as shown by several studies, other variables have shown indirect effects on PTG, such as resilience, challenge appraisal, distress and challenge to core beliefs (e.g. Wilson et al., 2014).

Several studies have found different PTG mediators: positive affect partially mediated the effects of general self-efficacy and expressive revealing on PTG and totally mediated the effects of emotional suppression on growth (Yu et al., 2014); cancer-related rumination partially mediated the relation between positive attentional bias and PTG (Chan et al., 2011); religiosity mediated the effect of ethnicity on PTG (Bellizzi et al., 2010); spirituality partially mediated the association between ethnicity and PTG (Smith et al., 2008); problem-focused coping fully mediated the relationship between dispositional optimism and PTG (Büyükaşik-Çolak et al., 2012); marital status moderated the relationship between the using of the combined exercise guidelines and PTG and BF (Crawford et al., 2015); trauma severity and seeking social support had a significant indirect effect on PTG (Morris & Shakespeare-Finch, 2011b); social support given by a close person has a moderator effect in the relationship between dispositional optimism and PTG (Bozo et al., 2009); positive reframing and religious coping mediated the relationship between secure attachment and PTG (Schmidt et al., 2012).

Empirical Studies with Intervention

The support group participation has, in fact, significant effect on the increase of growth report, in accordance with some studies (e.g. Kent et al., 2013; Roepke, 2014). In this systematic review studies with interventions have been included, with the specific purpose of assessing whether the implemented programs had a significant impact on growth scores, over time.

In what regards the empirical studies with interventions, Labelle et al. (2015) (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) and Pat-Horenczyk and colleagues (2015) (a cognitive-behaviour group intervention) found that the intervention group reported higher PTG than the control group. In addition, several studies found that the effect of the intervention group was significant in the post-intervention assessment (i.e. immediately after completion of the program), both on BF - Antoni et al. (2006) (Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management) and on PTG - Hawkes et al. (2014) (Multiple Health Behaviour Change Intervention) and Stafford et al. (2013) (Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy).

Moreover, the effects of the group intervention on growth were showed also longitudinally. The intervention group showed higher levels of growth at follow-up assessments, namely 4 weeks (Kállay & Baban (2008) (Expressive Writing Program); 3 months (Stafford et al., 2013); 6 months (Cameron et al. 2007) (Psychosocial Support Program); and 12 months (Antoni et al., 2006; Cameron et al., 2007; Hawkes et al., 2014). Other study did not show a significant effect of group intervention on PTGI total score, but showed on some PTGI domains (Garlick et al., 2011) (Psycho-Spiritual Integrative Therapy).

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this systematic review was to identify the variables associated with growth in patients with cancer diagnosis. Other systematic reviews were performed in the field of PTG and cancer; however, the objectives were different from this one. A previous systematic review entailed the psychosocial factors associated with PTG in breast cancer survivors (Kolokotroni et al., 2014) and other study reviewed PTG and PTSD among breast cancer patients (Koutroli et al., 2012). With a more comprehensive sample of participants with diverse types of cancer, Stanton and colleagues (2006) presented a systematic review about the perception of growth among cancer patients. In this study, authors selected cross-sectional and longitudinal studies and used both constructs to define growth: BF and PTG. However, the papers selected were published until 2005 and the intervention studies that have assessed PTG as an intervention outcome were not included in that review. Other systematic review and meta-analysis from Shand and colleagues (2015) analyzed, specifically, the correlations between PTG/PTSD and psychosocial and socio-demographic variables without assessing studies with intervention programs and with statistical analyses besides correlation analysis. Moreover, Roepke (2014) presented a systematic review of studies that assessed PTG as a result (primary or secondary) of a group intervention, without including other empirical studies (without intervention). Thus, the strengths of the current systematic review are: a) the inclusion of empirical studies with and without intervention and across all types of cancer; b) the inclusion of PTG, as well as similar constructs to define growth (BF, positive life changes, adversarial growth, stress-related growth); c) the identification of both correlated and predicted variables (socio-demographic, clinical and psychosocial) of growth; d) assessment of the overall quality of the studies with and without intervention with a jury of five researchers and inter-rater agreement coefficient calculation for 80% of the studies. Therefore, the inclusion of all constructs representative of growth and all types of cancer as well as the diversity of study design will allow a wider and more informed conclusion about the correlates/predictors of growth in cancer patients.

The results of the analyzed studies indicated that PTG is associated with age, educational level, household income, stage of cancer and physical activity/exercise; is not associated with gender, number of children, type of treatment, time since treatment, time since diagnosis, and type of surgery. Despite the majority of studies confirmed the relations with these variables, some associations remained incongruent, such as the relation of PTG and marital and professional status, type of cancer as well as type, quality, and efficacy of medical treatments, as mentioned by Casellas-Grau et al. (2017).

In what regards the psychosocial variables, the majority of studies confirmed that PTG was associated with the perception of cancer as a life-threatening event. This assumption is in accordance with the theoretical model of PTG from Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996; 2004), in which a traumatic event has to be perceived as stressfulness to trigger the challenge of core beliefs and the cognitive processing (i.e. intrusive and deliberate rumination), which in turn leads to PTG (Taku & Oshio, 2015). Moreover, a study from Taku and Oshio (2015) supported this perspective by showing that PTG can be raised in persons that perceived low to middle levels of stress in the aftermath of the traumatic event.

In addition, PTG is associated with positive adaptive coping, problem-focused coping, emotional-focused coping, positive reframing and religious coping. In the context of cognitive processing related variables, PTG was positively associated with intrusiveness, deliberate rumination and challenge to core beliefs. Contrary to other systematic review (Kolokotroni et al., 2014), PTG seemed to be associated with both sides (intrusive vs. deliberate) of cognitive processing. However, it is noteworthy that the challenge to core beliefs, deliberate and intrusive rumination have been barely explored in the literature, since only recently these variables have been included in studies about PTG in cancer patients. Thus, we suggest the analysis of the relationship between PTG and the cognitive process in further studies. Intrusiveness (not intrusive rumination) has been evaluated in a large number of studies, proving to be positively associated with PTG (Danhauer et al., 2013a: 2015; Dunn et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2014).

Additionally, other variables related to positive psychology were significantly associated with PTG, such as optimism, gratitude, happiness, openness to experience, hope and spirituality. However, only a reduced number of studies have explored the relations of PTG and these variables. Furthermore, findings from a systematic review of 12 studies that assessed the relationship between PTG and optimism indicated that this relationship remains unclear (Bostock et al., 2009). In this sense, more studies relating PTG and spiritual or positive outcomes are strongly suggested in order to enhance the understanding about these correlations.

Consistent to previous systematic review with a sample of breast cancer patients (Kolokotroni et al., 2014), perceived social support was positively associated with PTG, among the majority of studies (Bozo et al., 2009; Cohen & Numa, 2011, etc). Among the types of social support, marital and family relationships have a strong influence on cancer patients' reports of growth, but only two studies (Cormio et al., 2015; Tanriverd et al., 2012) have reported significant associations between these particular type of social support and PTG. In fact, satisfactory social support provided from family members or close friends may facilitate the emotional disclosure and the cognitive processing about the traumatic experience, which in turn may potentiate higher levels of growth (Cormio et al., 2015).

Physical variables were also barely studied. Only one study reported a significant association between PTG and cortisol slope (Diaz et al., 2014). Moreover, some variables remain incongruent such as depression, distress and PTSD symptoms. The relationship between PTG and these variables was significant in some studies but not significant in others.

A minor number of studies (n = 17) that assessed growth as BF were found in this review. Regarding socio-demographic and clinical variables, gender, marital status, stage of cancer, type of cancer, and type of treatment were not significantly associated with BF in the most of the studies. However, it is not clear if age, educational level and time since diagnosis were significantly associated with BF, since contrary results among studies were found. In what concerns psychosocial variables, BF was associated with positive active coping, positive reappraisal, social support and optimism; and not significantly associated with quality of life, anxiety, and depression.

A comment about the differences between PTG and BF seems necessary. In this review, three studies found a positive association between BF and PTG (Baník & Gajdoová, 2014; Li et al., 2015; Mols et al., 2009). In fact, these are two similar constructs but whose reports suggested significant content differences between them. Thus, “Reports of benefit finding might serve a more avoidant and self-protective function for individual with low personal resources (e.g. low optimism or self-efficacy) and might indicate more tangible positive change for those with more substantial resources, with distinct adaptive consequences” (Stanton et al., 2006, p.169). In addition, it is important to note that some studies have reported a specific variable (e.g. BF) but used a measurement scale that does not match the specific concept (e.g. PTGI) (e.g. Kallay & Baban, 2008; Thornton et al., 2012). This fact confirms the difficulties encountered in the literature to define the conceptual boundaries between concepts related to growth (Stanton et al., 2006).

Regarding studies with intervention, the results suggested that the participation in group interventions may increase the report of growth. These results should be interpreted with caution, since we found a small number of studies that assessed growth as primary or secondary outcome (n = 8) and none of those interventions has designed an intervention to promote growth, which certainly may potentiate other conditions to facilitate the development of growth.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. First of all, this review included only published studies, which might have affected the results obtained, since some studies that might be in course but not published may produce some interesting results that were not comprised in this review. Also, this review was limited in that only quantitative studies were included and studies that used a qualitative or mixed design were excluded. Thus, the understanding of growth in the aftermath of a trauma such as cancer may be incomplete without the reports that could be obtain with studies with qualitative methodology.

In this review, we found a small number of studies assessing BF, which may limit the comparison of predictors of PTG and BF. Also, the review of moderator analysis was based on a limited number of studies, restraining our confidence in these findings. Future research focused on mediation and moderation effects is needed.

In what regards the studies with group interventions, studies that published self-help group interventions that were moderated by a cancer patient or survivor and not by a psychologist, a nurse or a therapist, were excluded. We intended to analyze the results of interventions with a psychotherapeutic nature and objectives; however, self-help groups may also promote PTG through the modeling, “helper therapy principle” and other group processes such as self-disclosure about experiences related to cancer. Although several different constructs were included to assess growth, the amount of variables that were assessed was limited and constricted to the variables used in the studies. In this sense, psychological, cognitive and clinical variables were presented in a larger number of studies when comparing with other social or environmental variables. Further research is required to evaluate other social variables that may have impact on the level of perceived growth (e.g. health care conditions; instrumental support; number of previous traumatic events). Positive variables such as optimism, gratitude or openness to experience should also be included in further studies, since only a few studies selected in this review showed the associations of PTG and these variables. To conclude, more studies that assess growth as a result of an intervention are recommended, in order to support the evidence of the impact of group programs in the perception of positive changes after cancer.

REFERENCES

Abdullah, L., Iman, M. F., Nik Jaafar, N. R., Zakaria, H., Rajandram, R. K., Mahadevan, R., ... & Shah, S. A. (2015). Posttraumatic growth, depression and anxiety in head and neck cancer patients: Examining their patterns and correlations in a prospective study. Psycho‐Oncology, 24, 894-900. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3740 [ Links ]

Antoni, M. H., Lechner, S. C., Kazi, A., Wimberly, S. R., Sifre, T., Urcuyo, K. R., ... & Carver, C. S. (2006). How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 74, 1143-1152. Doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1143 [ Links ]

APA Publications and Communications Board Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards (2008). Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be? American Psychologist, 63, 848-849. [ Links ]

Baník, G., & Gajdoová, B. (2014). Positive changes following cancer: posttraumatic growth in the context of other factors in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22, 2023-2029. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2217-0

Barskova, T, & Oesterreich, R. (2009). Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil, 31(21), 1709-1733. Doi: 10.1080/09638280902738441 [ Links ]

Bellizzi, K. M., & Blank, T. O. (2006). Predicting posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology, 25(1), 47-52. Doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.47 [ Links ]

Bellizzi, K. M., Smith, A. W., Reeve, B. B., Alfano, C. M., Bernstein, L., Meeske, K., ... & Ballard-Barbash, R. R. (2010). Posttraumatic growth and health-related quality of life in a racially diverse cohort of breast cancer survivors. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(4), 615-626. Doi: 10.1177/1359105309356364 [ Links ]

Bostock, L., Sheikh, A. I., & Barton, S. (2009). Posttraumatic growth and optimism in health-related trauma: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 16, 281-296. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9175-6 [ Links ]

Bozo, Ö., Gündoğdu, E., & Büyükaşik-Çolak, C. (2009). The moderating role of different sources of perceived social support on the dispositional optimism - Posttraumatic growth relationship in postoperative breast cancer patients. Journal of health psychology, 14, 1009-1020. Doi: 10.1177/1359105309342295 [ Links ]

Brix, S. A., Bidstrup, P. E., Christensen, J., Rottmann, N., Olsen, A., Tjønneland, A., ... & Dalton, S. O. (2013). Post-traumatic growth among elderly women with breast cancer compared to breast cancer-free women. Acta Oncologica, 52, 345-354. Doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.744878 [ Links ]

Bussell, V. A., & Naus, M. J. (2010). A longitudinal investigation of coping and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 28(1), 61-78. Doi: 10.1080/07347330903438958 [ Links ]

Büyükaşik-Çolak, C., Gündoğdu-Aktürk, E., & Bozo, Ö. (2012). Mediating role of coping in the dispositional optimism-posttraumatic growth relation in breast cancer patients. The Journal of Psychology, 146, 471-483. Doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.654520 [ Links ]

Cameron, L. D., Booth, R. J., Schlatter, M., Ziginskas, D., & Harman, J. E. (2007). Changes in emotion regulation and psychological adjustment following use of a group psychosocial support program for women recently diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 16, 171-180. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1050 [ Links ]

Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Triplett, K. N., Vishnevsky, T., & Lindstrom, C. M. (2011). Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes : The event related rumination inventory. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24, 137-156. Doi: 10.1080/10615806.2010.529901 [ Links ]

Casellas-Grau, A., Font. A., & Vives, J. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in breast cancer. A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 9-19. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3353 [ Links ]

Casellas‐Grau, A., Ochoa, C., & Ruini, C. (2017). Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer. A systematic and critical review. Psycho‐oncology.1-12. Doi: 10.1002/pon.4426 [ Links ]

Cavell, S., Broadbent, E., Donkin, L., Gear, K., & Morton, R. P. (2015). Observations of benefit finding in head and neck cancer patients. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 273, 1-7. Doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3527-7 [ Links ]

Chan, M. W., Ho, S. M., Tedeschi, R. G., & Leung, C. W. (2011). The valence of attentional bias and cancer‐related rumination in posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 20, 544-552. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1761 [ Links ]

Cohen, M., & Numa, M. (2011). Posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: a comparison of volunteers and non‐volunteers. Psycho‐Oncology, 20(1), 69-76. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1709 [ Links ]

Cordova, M. J., Giese-Davis, J., Golant, M., Kronenwetter, C., Chang, V., & Spiegel, D. (2007). Breast cancer as trauma: Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 14, 308-319. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-007-9083-6 [ Links ]

Cormio, C., Romito, F., Giotta, F., & Mattioli, V. (2015). Post-traumatic Growth in the Italian Experience of Long-term Disease-free Cancer Survivors. Stress and health, 31, 189-196. Doi: 10.1002/smi.2545 [ Links ]

Crawford, J. J., Vallance, J. K., Holt, N. L., & Courneya, K. S. (2014). Associations between exercise and posttraumatic growth in gynecologic cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23, 705-714. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2410-1 [ Links ]

Danhauer, S. C., Case, L. D., Tedeschi, R., Russell, G., Vishnevsky, T., Triplett, K., ... & Avis, N. E. (2013). Predictors of posttraumatic growth in women with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 22, 2676-2683. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3298 [ Links ]

Danhauer, S. C., Russell, G., Case, L. D., Sohl, S. J., Tedeschi, R. G., Addington, E. L., ... & Avis, N. E. (2015). Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth and Associated Characteristics in Women with Breast Cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49, 650-659. Doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9696-1 [ Links ]

Danhauer, S. C., Russell, G. B., Tedeschi, R. G., Jesse, M. T., Vishnevsky, T., Daley, K., ... & Powell, B. L. (2013). A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute leukemia. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings, 20(1),13-24. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9304-5 [ Links ]

Diaz, M., Aldridge-Gerry, A., & Spiegel, D. (2014). Posttraumatic growth and diurnal cortisol slope among women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 44, 83-87. Doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.03.001 [ Links ]

Dunn, J., Occhipinti, S., Campbell, A., Ferguson, M., & Chambers, S. K. (2010). Benefit finding after cancer: The role of optimism, intrusive thinking and social environment. Journal of Health Psychology, 16 (1), 169-177. Doi: 10.1177/1359105310371555 [ Links ]

Garland, S. N., Valentine, D., Desai, K., Li, S., Langer, C., Evans, T., & Mao, J. J. (2013). Complementary and alternative medicine use and benefit finding among cancer patients. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 19, 876-881 Doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0964 [ Links ]

Garlick, M., Wall, K., Corwin, D., & Koopman, C. (2011). Psycho-spiritual integrative therapy for women with primary breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 18(1), 78-90. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9224-9 [ Links ]

Harding, S., Sanipour, F., & Moss, T. (2014). Existence of benefit finding and posttraumatic growth in people treated for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. PeerJ, 2:e256. Doi: 10.7717/peerj.256 [ Links ]

Harrington, S., McGurk, M., & Llewellyn, C. D. (2008). Positive consequences of head and neck cancer: key correlates of finding benefit. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 26, 43-62. Doi: 10.1080/07347330802115848 [ Links ]

Hawkes, A. L., Pakenham, K. I., Chambers, S. K., Patrao, T. A., & Courneya, K. S. (2014). Effects of a multiple health behavior change intervention for colorectal cancer survivors on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 48(3), 359-370. Doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9610-2 [ Links ]

Heidarzadeh, M., Rassouli, M., Shahbolaghi, F. M., Majd, H. A., Karam, A. M., Mirzaee, H., & Tahmasebi, M. (2014). Posttraumatic growth and its dimensions in patients with cancer. Middle East Journal of Cancer, 5(1), 23-29. Retrived from http://mejc.sums.ac.ir/index.php/mejc/article/view/142 [ Links ]

Ho, S., Rajandram, R. K., Chan, N., Samman, N., McGrath, C., & Zwahlen, R. A. (2011). The roles of hope and optimism on posttraumatic growth in oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncology, 47, 121-124. Doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.015 [ Links ]

Kállay, E., & Baban, A. (2008). Emotional benefits of expressive writing in a sample of Romanian female cancer patients. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 12(1), 115-129. Retrieved from http://www.ascred.ro/images/attach/Emotional%20benefits%20of%20expressive%20writing%20in%20a%20sample%20of%20romanian%20female%20cancer%20patients.pdf [ Links ]

Kent, E. E., Alfano, C. M., Smith, A. W., Bernstein, L., McTiernan, A., Baumgartner, K. B., & Ballard-Barbash, R. (2013). The roles of support seeking and race/ethnicity in posttraumatic growth among breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 31, 393-412. Doi: 10.1080/07347332.2013.798759 [ Links ]

Kinsinger, D. P., Penedo, F. J., Antoni, M. H., Dahn, J. R., Lechner, S., & Schneiderman, N. (2006). Psychosocial and sociodemographic correlates of benefit‐finding in men treated for localized prostate cancer. Psycho‐Oncology,15, 954-961. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1028 [ Links ]

Kolokotroni, P., Anagnostopoulos, F., & Tsikkinis, A. (2014). Psychosocial Factors Related to Posttraumatic Growth in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Review. Women and Health, 24, 569-592. Doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.899543 [ Links ]

Koutroli, N., Anagnostopoulos, F., & Potamianos, G. (2012). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Growth in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Women and Health, 52, 503-516. Doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.679337 [ Links ]

Labelle, L. E., Lawlor-Savage, L., Campbell, T. S., Faris, P., & Carlson, L. E. (2015). Does self-report mindfulness mediate the effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on spirituality and posttraumatic growth in cancer patients? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10, 153-166. Doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.927902 [ Links ]

Lelorain, S., Bonnaud-Antignac, A., & Florin, A. (2010). Long term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 17(1), 14-22. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9183-6 [ Links ]

Li, Y. C., Yeh, P. C., Chen, H. W., Chang, Y. F., Pi, S. H., & Fang, C. K. (2015). Posttraumatic growth and demoralization after cancer: The effects of patients' meaning-making. Palliative and Supportive Care, 13, 1449-1458. Doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000048 [ Links ]

Liberati, A., Altman, D.G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P.C., Ioannidis, J.P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [ Links ]

Llewellyn, C. D., Horney, D. J., McGurk, M., Weinman, J., Herold, J., Altman, K., & Smith, H. E. (2013). Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 22(1), 97-105. Doi: 10.1002/pon.2065 [ Links ]

Martins da Silva, S. I., Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2011). Growing after breast cancer: A controlled comparison study with healthy women. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16, 323-340. Doi: 10.1080/15325024.2011.572039 [ Links ]

Mols, F., Vingerhoets, A. J., Coebergh, J. W. W., & van de Poll-Franse, L. V. (2009). Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychology and Health, 24(5), 583-595. Doi: 10.1080/08870440701671362 [ Links ]

Morrill, E. F., Brewer, N. T., O'Neill, S. C., Lillie, S. E., Dees, E. C., Carey, L. A., & Rimer, B. K. (2008). The interaction of post‐traumatic growth and post‐traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psycho‐Oncology, 17, 948-953. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1313 [ Links ]

Morris, B. A., & Shakespeare-Finch, J. (2011a). Cancer diagnostic group differences in posttraumatic growth: accounting for age, gender, trauma severity, and distress. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16, 229-242. Doi: 10.1080/15325024.2010.519292

Morris, B. A., & Shakespeare‐Finch, J. (2011b). Rumination, post‐traumatic growth, and distress: structural equation modelling with cancer survivors. Psycho‐Oncology, 20, 1176-1183. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1827

Morris, B. A., Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Scott, J. L. (2007). Coping processes and dimensions of posttraumatic growth. The Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 2007-1, 1-12. Retrieved from http://eprints.utas.edu.au/4419/ [ Links ]

Mystakidou, K., Tsilika, E., Parpa, E., Kyriakopoulos, D., Malamos, N., & Damigos, D. (2008). Personal growth and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer. The Breast, 17, 382-386. Doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.01.006 [ Links ]

Park, C. L., Edmondson, D., & Blank, T. O. (2009). Religious and Non‐Religious Pathways to Stress‐Related Growth in Cancer Survivors. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 1, 321-335. Doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01009.x [ Links ]

Pat-Horenczyk, R., Perry, S., Hamama-Raz, Y., et al. (2015). Posttraumatic Growth in Breast Cancer Survivors: Constructive and Illusory Aspects. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 214-222. Doi: 10.1002/jts.22014

Posluszny, D. M., Baum, A., Edwards, R. P., & Dew, M. A. (2011). Posttraumatic growth in women one year after diagnosis for gynecologic cancer or benign conditions. Journal of psychosocial oncology, 29, 561-572. Doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.599360 [ Links ]

Rahmani, A., Mohammadian, R., Ferguson, C., Golizadeh, L., Zirak, M., & Chavoshi, H. (2012). Posttraumatic growth in Iranian cancer patients. Indian journal of cancer, 49, 287-292. Doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.104489 [ Links ]

Rand, K. L., Cripe, L. D., Monahan, P. O., Tong, Y., Schmidt, K., & Rawl, S. M. (2012). Illness appraisal, religious coping, and psychological responses in men with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 1719-1728. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1265-y [ Links ]

Roepke, A. M. (2014). Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(1), 129-142. Doi: 10.1037/a0036872 [ Links ]

Ruini, C., Offidani, E., & Vescovelli, F. (2014). Life Stressors, Allostatic Overload, and Their Impact on Posttraumatic Growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 20, 109-122. Doi: 10.1080/15325024.2013.830530 [ Links ]

Ruini, C., Vescovelli, F., & Albieri, E. (2013). Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: new insights into its relationships with well-being and distress. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings, 20, 383-391. Doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9340-1 [ Links ]

Salsman, J. M., Segerstrom, S. C., Brechting, E. H., Carlson, C. R., & Andrykowski, M. A. (2009). Posttraumatic growth and PTSD symptomatology among colorectal cancer survivors: a 3‐month longitudinal examination of cognitive processing. Psycho‐Oncology, 18(1), 30-41. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1367 [ Links ]

Schmidt, S. D., Blank, T. O., Bellizzi, K. M., & Park, C. L. (2012). The relationship of coping strategies, social support, and attachment style with posttraumatic growth in cancer survivors. Journal of Health Psychology, 17, 1033-1040. Doi: 10.1177/1359105311429203 [ Links ]

Schroevers, M. J., Kraaij, V., & Garnefski, N. (2011). Cancer patients' experience of positive and negative changes due to the illness: relationships with psychological well‐being, coping, and goal reengagement. Psycho‐Oncology, 20, 165-172. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1718 [ Links ]

Schulz, U., & Mohamed, N. E. (2004). Turning the tide: Benefit finding after cancer surgery. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 653-662. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.019 [ Links ]

Scrignaro, M., Barni, S., & Magrin, M. E. (2011). The combined contribution of social support and coping strategies in predicting post‐traumatic growth: a longitudinal study on cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncology, 20, 823-831. Doi: 10.102/pon.1782 [ Links ]

Shand, L. K., Cowlishaw, S., Brooker, J. E., Burney, S., and Ricciardelli, L. A. (2015), Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and growth in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology, 24, 624-634. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3719

Silva, S. M., Crespo, C., & Canavarro, M. C. (2012). Pathways for psychological adjustment in breast cancer: A longitudinal study on coping strategies and posttraumatic growth. Psychology & Health, 27, 1323-1341. Doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.676644 [ Links ]

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Bernard, J. F., & Baumgartner, K. B. (2008). Posttraumatic growth in non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women with cervical cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 26, 91-109. Doi: 10.1080/07347330802359768 [ Links ]

Smith, S. K., Samsa, G., Ganz, P. A., & Zimmerman, S. (2014). Is there a relationship between posttraumatic stress and growth after a lymphoma diagnosis? Psycho‐Oncology, 23, 315-321. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3419 [ Links ]

Soo, H., & Sherman, K. A. (2015). Rumination, psychological distress and post‐traumatic growth in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 24(1), 70-79. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3596 [ Links ]

Stafford, L., Foley, E., Judd, F., Gibson, P., Kiropoulos, L., & Couper, J. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive group therapy for women with breast and gynecologic cancer: a pilot study to determine effectiveness and feasibility. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 3009-3019. Doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1880-x [ Links ]

Stanton, A. L., Bower, J. E., & Low, C. A. (2006). Posttraumatic Growth After Cancer. In L. G. Calhoun, & R. G. Tedeschi, Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice (138-175). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Strack, J., Lopes, P., & Gaspar, M. (2010). Reappraising cancer: life priorities and growth. Onkologie, 33, 369-374. Doi: 10.1159/000315768 [ Links ]

Svetina, M., & Nastran, K. (2012). Family relationships and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients. Psychiatria Danubina, 24, 298-306. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.pt/scholar?hl=en&q=Family+relationships+and+post-traumatic+growth+in+breast+cancer+patients.+&btnG=&as_sdt=1%2C5&as_sdtp [ Links ]

Taku, K., & Oshio, A. (2015). An item-level analysis of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Relationships with an examination of core beliefs and deliberate rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 156-160. Doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.025 [ Links ]

Tang, S. T., Lin, K. C., Chen, J. S., Chang, W. C., Hsieh, C. H., & Chou, W. C. (2015). Threatened with death but growing: changes in and determinants of posttraumatic growth ov20er the dying process for Taiwanese terminally ill cancer patients. PsychoXOncology, 24, 147-154. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3616

Tanriverd, D., Savaş, E., & Can, G. (2012). Posttraumatic growth and social support in Turkish patients with cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 13, 4311-4314. Doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.9.4311 [ Links ]

Tanyi, Z., Szluha, K., Nemes, L., Kovács, S., & Bugán, A. (2015). Positive consequences of cancer: exploring relationships among posttraumatic growth, adult attachment, and quality of life. Tumori, 101, 223-231. Doi: 10.5301/tj.5000244 [ Links ]

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L.G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 455-471. Doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305 [ Links ]

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1- 18. [ Links ]

Thombre, A., Sherman, A. C., & Simonton, S. (2010). Posttraumatic growth among cancer patients in India. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 15-23. Doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9229-0 [ Links ]

Thornton, A. A., Owen, J. E., Kernstine, K., Koczywas, M., Grannis, F., Cristea, M., ... & Stanton, A. L. (2012). Predictors of finding benefit after lung cancer diagnosis. Psycho‐Oncology, 21, 365-373. Doi: 10.1002/pon.1904 [ Links ]

Thuné-Boyle, C. V., Stygall, J., Keshtgar, M. R. S., Davidson, T. I., & Newman, S. P. (2011). The influence of religious/spiritual resources on finding positive benefits from a breast cancer diagnosis. Counseling et spiritualité, 30(1), 107-134. Retrieved from http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=24209260 [ Links ]

Wang, M. L., Liu, J. E., Wang, H. Y., Chen, J., & Li, Y. Y. (2014). Posttraumatic growth and associated socio-demographic and clinical factors in Chinese breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 478-483. Doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.04.012 [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Zhu, X., Yang, Y., Yi, J., Tang, L., He, J., ... & Yang, Y. (2015). What factors are predictive of benefit finding in women treated for non‐metastatic breast cancer? A prospective study. Psycho‐Oncology, 24, 533-539. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3685 [ Links ]

Wilson, B., Morris, B. A., & Chambers, S. (2014). A structural equation model of posttraumatic growth after prostate cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 23, 1212-1219. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3546 [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2015). Cancer Fact sheet nº297. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Accessed on 25 February 2016. [ Links ]

Yu, Y., Peng, L., Tang, T., Chen, L., Li, M., & Wang, T. (2014). Effects of emotion regulation and general self-efficacy on posttraumatic growth in Chinese cancer survivors: assessing the mediating effect of positive affect. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 473-478. Doi: 10.1002/pon.3434 [ Links ]

FUNDING

This research was funded by Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology [FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia], Grant/Award Number: SFRH/BD/81515/2011 and by WJCR – William James Center for Research, which is funded by FCT (grant UID/PSI/04810/2013).Recebido em 22 de Fevereiro de 2018/ Aceite em 04 de Junho de 2018