Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.20 no.2 Lisboa ago. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15309/19psd200217

Acculturation, anxiety and depression among haitian immigrants in southern brazil

Aculturação, ansiedade e depressão em imigrantes haitianos na região sul do brasil

Alice Brunnet1,3, João Weber, Laura Bolaséll3, Ezquiel Cargnelutti3, Christian Kristensen3, & Adolfo Pizzinato4

1Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, Laboratory Psy-DREPI EA 7458, Dijon, France, brunnetalice@gmail.com

2Department of Psychology, FSG - Centro Universitário da Serra Gaúcha, Caxias, Brazil, jlweber27@gmail.com

3Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Graduate Program in Psychology, School of Health Sciences, Porto Alegre, Brasil, lauratbolasell@gmail.com, ezequielcargnelutti@gmail.com, christian.kristensen@pucrs.br

4Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Department of Developmental Psychology and Personality, Porto Alegre, Brazil, adolfopizzinato@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Acculturation refers to changes that occur when people from different cultural backgrounds encounter a new cultural environment. Such changes may play an important role in mental health. The present study investigates the relationships between acculturation, anxiety and depression in 64 Haitians who migrated to Brazil between 2010 and 2016. Participants answered a sociodemographic questionnaire, the Immigrant Acculturation Scale, and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist - 27. Participants reported low levels of anxiety and depression symptoms and the most adopted acculturation strategy was integration. An assimilationist acculturation orientation was associated with lower levels of anxiety and a separationist orientation was linked to higher levels of depression. Contradicting our initial hypotheses, the final anxiety model negatively associated language separation with high anxiety symptoms. In general, the participants of the present study seemed to be well adapted to the Brazilian culture. However, acculturation strategies in our study varied across domains and were influenced by sociodemographic variables as time since migration and being employed. Considering that Brazil is a large and multi-cultural country, further research should be conducted in different parts of the country and with various migrant groups in order to better understand the acculturation phenomena.

Keywords: migration, acculturation, anxiety, depression, mental health

RESUMO

A aculturação é definida como mudanças que ocorrem quando pessoas de diferentes contextos culturais encontram uma nova cultura. Essas mudanças podem ter um papel importante na saúde mental dos indivíduos. O presente estudo teve como objetivo principal investigar as relações entre aculturação, ansiedade e depressão em 64 haitianos que imigraram para o Brasil entre os anos de 2010 e 2016. Os participantes responderam a um questionário sócio demográfico e as escalas Immigrant Acculturation Scale e Hopkins Symptom Checklist - 27. A orientação aculturativa mais apontada pelos participantes foi a integrativa e a média dos sintomas de ansiedade e depressão mostrou-se abaixo do ponto de corte da escala. A orientação aculturativa de assimilação foi associada com baixos níveis de ansiedade, e a orientação aculturativa de separação foi associada com altos níveis de depressão. Contrariamente a nossa hipótese inicial, os participantes que apresentaram uma maior separação na área da linguagem, relataram níveis inferiores de ansiedade. Os participantes do presente estudo relataram, em sua maioria, uma boa adaptação ao contexto cultural brasileiro. No entanto, as orientações aculturativas foram influenciadas por questões sócio demográficas, como o tempo desde a migração e o emprego. Considerando a extensão territorial do Brasil, bem como sua característica multicultural, estudos em outras regiões brasileiras e com diferentes grupos de migrantes devem ser realizados afim de possibilitar uma melhor compreensão do fenômeno da aculturação de migrantes no país.

Palavras-chave: migração, aculturação, ansiedade, depressão, saúde mental

Haitian migration to Brazil is a recent phenomenon and occurs mostly since the earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010. Currently, around 40.000 Haitian immigrants reside among the Brazilian population of 202 million, being the third largest local immigrant population (Handerson, 2015). Studies suggest that acculturation strategies may influence the mental health of migrants (Drogendijk, Van Der Velden, & Kleber, 2012; Gonidakis et al., 2011; Hilario, Vo, Johnson, & Saewyc, 2014). However, few studies exploring this association were conducted in developing countries (Yoon et al., 2013).

The impact of migration on mental health is still controversial. Immigrants are frequently exposed to risk factors such as low socioeconomic status, low educational level and increased psychological distress. Despite such risks, a number of epidemiological studies indicate that immigrants have lower rates of psychiatric disorders than natives (Breslau et al., 2007). This phenomenon is called “immigrant paradox” and has been studied mainly in the United States with Latin American migrants (Bjornstrom & Kuhl, 2014; Bostean, 2013; Lau et al., 2013). Nevertheless, studies conducted in other countries have reported high rates of mental illnesses (Abebe, Lien, & Hjelde, 2012; Aragona & Pucci, 2012). A systematic review including 10 studies from different countries explored rates of depression and anxiety-related syndromes and disorders among labor immigrants (Lindert et al., 2009). The authors found a combined prevalence of 20% for depression and 21% for anxiety. Furthermore, a higher economic development of the host country was associated with lower anxiety and depression symptoms among labor immigrants (Lindert et al., 2009).

Rates of anxiety and depression in immigrants are influenced by a complex interaction between protection and risk factors (Lau et al., 2013). Scientific literature describes the following risk factors for mental health problems in immigrants: low access to health systems, poor knowledge of the local language, longer time spent in the host country, lower age at migration and low levels of acculturation (Aragona & Pucci, 2012; Liddell et al., 2013). Specifically, acculturation seems to play an important role as a risk or protection factor for mental disorders in this population (Drogendijk et al., 2012; Fassaert et al., 2011; Gonidakis et al., 2011, Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010).

Acculturation can be defined as the process of change that occurs when people or groups from different cultural backgrounds come into regular contact with a new cultural environment (Sam & Berry, 2010). Berry (1980, 1997) proposed a Bidimensional Model of Acculturation delineating four acculturation strategies: (1) integration, utilized when immigrants wish to maintain part of their cultural identity, as well as to adopt some elements from the new culture; (2) assimilation, adopted by individuals who do not wish to maintain their cultural identity and thus aim to adopt a new cultural identity through regular contact with a new culture; (3) separation, when immigrants refrain from adopting any elements of the new culture, maintaining their original cultural identity; and (4) marginalization, which occurs with individuals that are unwilling or unable to maintain their cultural heritage and to adopt elements of the new cultural environment. Bourhis, Moïse, Perreault, and Senécal (1997) later developed the Interactive Acculturation Model and divided the marginalization strategy into anomie and individualism. Individuals prone to cultural alienation adopt anomie, whereas immigrants who dissociate themselves both from their original culture and the new culture may adopt an individualist orientation, not because they feel marginalized, but because they prefer to identify themselves as individuals rather than as members of a group.

Certain acculturation orientations have a relationship with mental health issues. Integrative strategies as “willingness to interact with individuals and their usual behaviors” and “developing skills to live in the host society” (e.g. language skills) have been associated with lower levels of psychological distress and depression symptoms, while marginalization strategies have been associated with higher levels of depression (Fassaert et al., 2011; Gonidakis et al., 2011; Morawa & Erim, 2014). Furthermore, the relationship between mental health and acculturation may vary according to sociodemographic variables such as gender and ethnicity. In the study by Fassaert et al. (2011), traditionalism predicted less distress among Moroccans, but not among Turkish migrants, whereas conservative norms and values were protective for Turkish men, but not for Turkish women.

Although Brazil is a country formed by immigrants, recent immigration is a phenomenon yet to be studied in depth. No studies investigating acculturation strategies in immigrants were found in the Brazilian literature, which is still very scarce regarding immigration studies. In the last 5 years, Brazil has seen a new wave of migration, composed mainly of Haitian, Senegalese and Ghanaians and concentrated in the south and southeast region of the country, where there are more labor opportunities. The southernmost Brazilian state, Rio Grande do Sul, concentrates a large portion of the Haitian population that has recently migrated. Official data from the International Organization for Migration (2015) indicate that there are currently 1575 registered Haitian immigrants in Rio Grande do Sul.

Besides variations in individuals factors, social aspects like immigration laws also play a role in acculturation and mental health (Morawa & Erim, 2014; Virta, Sam, & Westin, 2004). Since 2012, every Haitian immigrant in Brazil receives a permanent visa for humanitarian issues arising from the earthquake of 2010 (Brazil, 2012). This visa is subject to laws regulating the immigrant status of foreigners in Brazil (Brazil, 1980), and requires that proof of residence and employment is provided within the first 5 years since immigration in order to remain permanently valid. Possession of this visa enables Haitian immigrants to acquire other documents that will give access to legal work and public services such as health, welfare and education. Societies with diverse immigration laws and legal practices may generate different environments for immigrants. Therefore, it is important to explore this phenomenon in different societies.

Considering that Brazilian migration policies are relatively open and that the Brazilian government confers legal status to all Haitian migrants, the country may prove to be an adequate environment for the study of acculturation phenomena and their influence on mental health. The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between acculturation orientations (regarding the domains of culture, endogamy/exogamy, work and language), anxiety and depression among Haitian immigrants in southern Brazil. We hypothesize that more integrative orientations will be associated with less anxiety and depression symptoms, whilst more exclusionist orientations, such as anomie and separation, will be associated with more symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Method

Participants

Interviews were conducted with 64 first generation immigrants from Haiti, fluent in French and residing in one of three cities in the district of Rio Grande do Sul. Immigrants invited to participate were referred by two different NGOs, a school offering Portuguese classes for immigrants or a labor union. Sample size calculation was based on the official data from the International Organization for Migration of 1,575 registered Haitian immigrants in Rio Grande do Sul, with a confidence level of 90% and a sampling error of 10%, what resulted in a sample of 64 participants. Included participants were (a) first generation immigrants from Haiti (b) with at least 18 years old and (c) able to speak French.

Procedures

The present study was accepted by the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul Ethics Committee (report number: 1.164.938). All participants provided written and informed consent before assessments and did not receive any compensation for participating in the study. Data collection lasted six months, from September 2015 to February 2016. The interviews were carried out by a Brazilian psychologist fluent in French in individual sessions of approximately 40 minutes. Immigrants unable to communicate in French were excluded from the study.

Material

Sociodemographic questionnaire

The sociodemographic questionnaire was developed for the present study, with questions assessing age, sex, educational level, profession, employment status, income, marital status, etc. It also contains questions regarding the immigration process, such as time of residence in Brazil, number of fluent languages, whether relatives live in Brazil or Haiti, among others.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist - 27 (HSC) (de Fouchier, 2013; Mollica, Wyshak, de Marneffe, Khuon, & Lavelle, 1987)

The HSC contains 27 self-report items answered through a 4-point Likert scale, investigating anxiety and depression symptoms. The items were developed based on Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder symptoms from the DSM-IV-TR. The French version of the checklist was translated, adapted and validated by de Fouchier (2013) with a Sub-Saharan African torture victim population, presenting satisfactory psychometric qualities. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the HSC in our sample was .84.

Immigrant Acculturation Scale (IAS) (Berry, Kim, Power, Young, & Bujaki, 1989; Bourhis, Barrette, El-Geledi, & Schmidt, 2009)

The IAS scale aims to investigate acculturation orientations of immigrants: integration, assimilation, separation, anomie and individualism in a self-administered 7-point Likert scale. Acculturation orientations were measured in four different domains of life: culture, endogamy/exogamy, employment and language, resulting in a 20-item instrument. We utilized the French version of the IAS adapted by Bourhis et al. (2009). This version was successfully utilized in studies with Haitian and Indian immigrants in Québec (Möise & Bourhis, 1996), North Africans in Paris (Barrette, Bourhis, Personnaz, & Personnaz, 2004) and with Asian and Hispanic descendants in California (Bourhis et al., 2009).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted on SPSS 20.0. Pearson and Spearman correlations, chi-square, Fisher’s exact test and t-tests were performed to investigate possible associations between demographic data, depression, anxiety and acculturation strategies. As shown on Table 1, the IAS distribution was asymmetric and participants tended to respond in a dichotomous manner. Thus, the IAS questions were transformed into dichotomous variables (low=0-3; high=5-7). The cutoff point used for the HSC was the median of this sample (symptoms of anxiety=1.2 and symptoms of depression=1.3). The suggested cutoff point of 2.5 by de Fouchier (2013) was derived from a highly traumatized refugee sample, and was considered too high for the present study. Variables that presented a significant association with symptoms of anxiety and depression were included in regressions models. A level of significance of p<0.05 was predetermined.

Results

Socio-Demographic Data

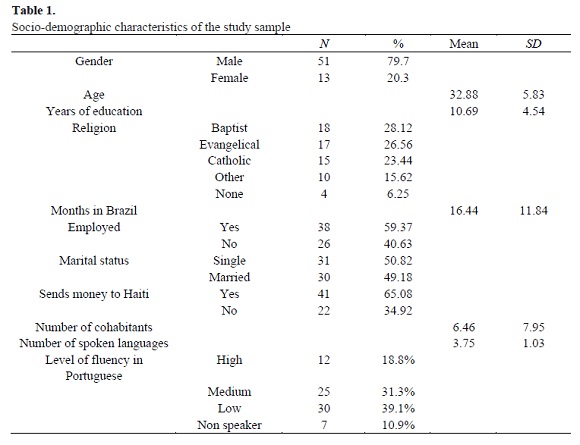

The sample consisted mainly of male (79.7%), religious (94.75%), employed (59.37%) and single (50.82%) participants, sharing their home with an average of 6.46 (SD=7.95) people. Mean age was 32.88 (SD=5.83) and the averages of months living in Brazil and years of study were 16.44 (SD=11.84) and 10.69 (SD=4.54) respectively. Furthermore, the majority of participants sent money to their families in Haiti (65.08%). Haitians reported an average of 3.75 (SD=1.03) languages spoken and a low level of fluency in Portuguese.

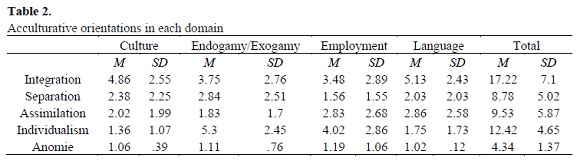

Acculturation

Results show that immigrants resorted mostly to integrative (M=17.44, DP=5.1) and individualist (M=12.45, SD=4.6) orientations in all domains assessed in the study. The less adopted orientation was anomie (M=4.5, SD=2.3). In the culture (M=4.86, SD=2.55) and language (M=5.13 SD=2.43) domains, participants adopted mostly the integrative orientation and in the endogamy/exogamy (M=5.3 SD=2.45) and employment (M=4.02 ==2.86) domains, the most adopted orientation was individualism. The frequencies for all orientations in each domain is shown in Table 2.

Spearman correlations and chi-square tests were performed to investigate associations between acculturation orientations and socio-demographic variables. Time since migration to Brazil appeared as an important factor, positively correlating with integration in employment (r=.326, p<.01), integration in language (r=.276, p<.05), individualism in language (r=.425, p<.01), anomie in endogamy/exogamy (r=.281, p<.05) and negatively correlating with assimilation in employment (r=-.259, p<.05). Other positive correlations included age at the time of assessment with culture assimilation (r=.326, p<.01) and the number of cohabitants with integration in language (r=.259, p<.05).

Chi-square tests were performed between the categorical sociodemographic variables and the transformed dichotomous acculturation orientations. Results were statistically significant between being a man and having higher integration in employment [X²(1)=11.11, p=.001], higher integration in endogamy/exogamy [X²(1)=6.85, p=.009], lower assimilation in language (Fischer’s exact test, p=.004) and higher integration in language (Fischer’s exact test, p<.001). Sending money to Haiti was associated with lower assimilation of the culture (Fischer’s p=.024) and lower assimilation in endogamy/exogamy (Fischer’s exact test p=.006). The findings also indicate that being employed was associated with higher integration in employment [X²(1)=9.11, p=.003], and higher integration in language [X²(1)=5.71, p=.017]. Lastly, regarding marital status, being married was associated with higher assimilation in language [Fischer’s exact test, p=.012].

Acculturation and mental health

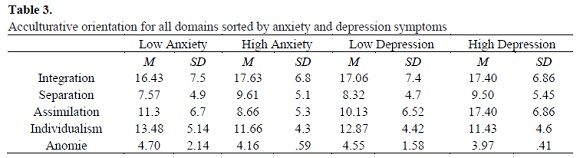

The means for each orientation of every domain are presented on Table 3, divided into low and high anxiety and depression scores. Even though differences between mean values were observed with the t-test, statistical significance was not achieved.

(M=1.3; DP=.030) and depression (M=1.3; DP=.32) mean scores were below the cutoff point previously established for the scale (M=2.5). A correlation was found between symptoms of anxiety and depression (r=.594, p<.001). No correlations were found between mental health and sociodemographic variables such as age, time spent in Brazil and years of study. Chi-square analysis pointed out that married participants had higher anxiety symptoms (X²(1)=3.84, p=0.50). Participants that needed to financially support their families in the country of origin presented more depression symptoms [X²(1)=5.52, p=.019]. Depression symptoms were higher in immigrants that did not report a religion [Fisher’s exact test, p=.049], however, this result should be interpreted carefully, as only four participants did not report a religion.

Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test were performed to explore differences between acculturation orientations and mental health symptoms. Participants with low culture separation also reported low depression symptoms, with a marginally significant score [X²(1)=3.78, p=.052]. Lower levels of culture assimilation were present in participants with higher anxiety symptoms (Fisher’s Exact Test, p=.030). Higher levels of anxiety were also present in participants with lower separation in the language domain [X²(1)=5.13, p=.024].

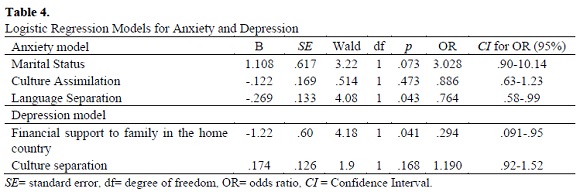

Logistic Regression results are reported on Table 4. Culture assimilation, language separation and marital status were included in the logistic regression model as independent variables with anxiety (cutoff point = 1.2) as a dependent variable. The model was significant [X²(3)=10.52, p<.015] and the Nagelkerke’s R² was 0.24, indicating that the model explained 24% of variance of anxiety scores. Individuals with higher language separation had 76% less chance of having high anxiety symptoms.

The depression model comprised the following variables: financial support to family in the home country and culture separation. The religion variable was not included due to the small number of participants that did not report a specific religious belief (n=4). The model attained significance [X²(2)=7.66, p=.022] and explained 16.3% of the variance [Nagelkerke R²= .163]. Participants that did not financially support their family in Haiti had 29% less risk for high levels of depression symptoms.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the association between acculturation orientations in different domains and the mental health variables of anxiety and depression symptoms. The main findings partially confirmed our previous hypotheses. The preliminary analyses showed that individuals with high culture assimilation presented low anxiety symptoms, as well as culture separation was higher in migrants with more depressive symptoms. However, these associations did not reach a significant level in the regression model. Previous research in acculturation and mental health describes integration strategies as negatively associated with poor mental health outcomes, which are in turn positively associated with separation (Behrens, del Pozo, Grosshennig, Sieberer, & Graef-Calliess, 2015; Yoon et al., 2013).

Surprisingly, the final anxiety model negatively associated language separation with high anxiety symptoms. We hypothesize that immigrants who prefer to speak their mother tongue are more in contact with the home culture of their compatriots, what may constitute a protective factor regarding anxiety symptoms. Behrens et al. (2015) found that immigrants with a segregative orientation had less depressive symptoms than those with an assimilative orientation. The authors suggested that symptoms were less salient in the first group of immigrants because they were less exposed to the host culture, and consequently did not face as many migration challenges.

Previous literature indicated that a separationist acculturation orientation was linked with depression symptoms. However, the depression model in our study did not have an acculturation variable as significantly associated with the dependent variable, as in the anxiety model. Previous studies also show the possibility of a lack of association between acculturation and mental health (Yoon et al., 2013). The model showed that other variables, rather than acculturation orientations, might be associated with mental health outcomes. In the present study, the need to support family members who are still in the home country seems to be an important influence in depression symptoms. Individual and environmental factors may be important mediators of the relationship between acculturation and mental health, but it is important to address the role of family (Lawton & Gerdes, 2014) and social support (Oppedal & Idsoes, 2015) as well. We hypothesize that most migrants that needed to provide to their families in the home country, in addition to living in a new country, were under more pressure to seek profitable labor and to remain employed.

The most adopted acculturation orientations were integration, in the culture and language domains, and individualism, in the employment and endogamy/exogamy domains. These orientations are described in the literature as positive (Berry, 1997; Bourhis et al.,1997) and are associated with positive mental health (Morawa & Erim, 2014; Behrens et al. 2015). The anomie orientation had been previously associated with lower quality of life and mental health (Bourhis et al., 1997), and was the least scored orientation in all domains in this study. Regarding general results, immigrants mostly adopted an integrative acculturation orientation, what demonstrates an attitude of openness towards the new community.

Acculturation strategies in our study varied across domains and were influenced by sociodemographic variables. Navas et al. (2005) endorse the importance of considering different domains and psychosocial issues when addressing the acculturation process, as well as Schwartz et al. (2010), who highlight the importance of studying acculturation as a multidimensional process. Differences in acculturative preferences across domains do not reflect a contradiction, but a more accurate perspective of how immigrants face the migration process, what leads to a more complex and relational understanding of this phenomenon (Navas, Rojas, García, & Pumares, 2007). With regard to the relationships between acculturation orientations and sociodemographic variables, the time since immigration appears to be an important factor, with a significant influence on integration and individualism. Results indicate that Haitian immigration in Brazil is indeed a recent phenomenon: the average time spent in the country was 16.44 months (SD= 11.84), with a maximum count of 48 months. Ramelli, Florack, Kosic, and Rohmann (2013) pointed out the importance of the initial months in the new country and of establishing contacts with members of the host community for a successful integration in the new culture.

Further variables significantly associated with greater integration included being a man and being employed. Although men reported to be more prone to integration, these results should be treated with caution due to the reduced number of women in the sample. According to Zamberlam, Corso, Címadon, and Bocchi (2014), the fact that most Haitian women have to stay at their home country taking care of their children is consistent with a smaller number of Haitian women in Brazil. Time also plays an important role for women in acculturation. Being given enough time in a more liberal society, women tend to seek more autonomy, entering the labor market and integrating themselves in the new context, what tends to modify her social role in relation to men (Alencar-rodrigues, Strey, & Espinosa, 2009).

There were no significant differences between the general results of acculturation orientations in different levels of anxiety and depression symptoms. Although several studies do not indicate this difference, there are important aspects to consider that may have affected these results. Firstly, the low anxiety and depression rates in our sample are in line with the immigrant paradox phenomenon described in the literature (Liddell et al., 2013). Furthermore, our population is characterized by a short time spent in the host country, and some studies indicate that mental health problems in immigrants increase over time (Breslau et al., 2007). Another issue to consider is the sample size, which does not allow broad generalizations to the target population. Finally, we return to the argument by Navas et al. (2007) and Schwartz et al. (2010) on the importance of understanding the acculturation process as sensitive to different domains and that the association with mental health factors proved to be sensitive to these areas as well.

The present study is the first to explore acculturation and mental health in a group of the new wave of immigrants in Brazil. Therefore, the study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small, a problem related to the difficulty of mapping and accessing this population. The cross-sectional study design is also a limitation, for it does not allow the assumption of causality between the measured variables. Moreover, the utilized assessment instruments did not allow for a DSM-5-oriented diagnosis of anxiety and depression disorders, but for an investigation of symptoms.

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world by area and population. Therefore, results may vary according to region. Further research should be conducted in different parts of the country in order to allow for comparisons. Other groups of recent immigrants such as the Senegalese, Ghanaian, Nigerian and Dominican should also be studied.

Although evidence suggested that having a religion was a protective factor towards depression, this result should be further explored with a larger sample and with an assessment instrument measuring the degree of religiosity, as this was an issue repeatedly raised by participants during data collection. Qualitative studies may also raise relevant information about the immigrant population and the Brazilian context. Lastly, interventions promoting health and including the participation of immigrants, members of the host society and peer networks should be considered. Focusing on the development of alternatives and supplementary material to mental health services might enable public policy providers to give a more appropriate assistance, one that is sensitive to the particularities of the immigrant population.

REFERENCES

Abebe, D. S., Lien, L., & Hjelde, K. H. (2012). what we know and don’t know about mental health problems among immigrants in Norway. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(1), 60-7. DOI: 10.1007/s10903-012-9745-9.

Alencar-rodrigues, R. D., Strey, M. N., & Espinosa, L. C. (2009). Marcas do gênero nas migrações internacionais das mulheres. Psicologia & Sociedade, 21(3), 421-430. [ Links ]

Aragona, M., & Pucci, D. (2012). Post-migration living difficulties as a significant risk factor for PTSD in immigrants: a primary care study. Italian Journal of Public Health, 9(3), 1-8. DOI: 10.2427/7525. [ Links ]

Barrette, G., Bourhis, R. Y., Personnaz, M., & Personnaz, B. (2004). Acculturation orientations of French and North African undergraduates in Paris. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28(5), 415-438. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.08.003. [ Links ]

Behrens, K., del Pozo, M. A., Grosshennig, A., Sieberer, M., & Graef-Calliess, I. T. (2015). How much orientation towards the host culture is healthy? Acculturation style as risk enhancement for depressive symptoms in immigrants. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(5), 498-505. DOI: 10.1177/0020764014560356. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Padilla, A. (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models and findings (pp. 9-25). Boulder: Westview. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5-34. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W., Kim, U., Power, S., Young, M., & Bujaki, M. (1989). Acculturation attitudes in plural societies. Applied Psychology, 38(2), 185-206. [ Links ]

Bjornstrom, E. E. S., & Kuhl, D. C. (2014). A different look at the epidemiological paradox: Self-rated health, perceived social cohesion, and neighborhood immigrant context. Social Science and Medicine, 120, 118-125. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.015. [ Links ]

Bostean, G. (2013). Does selective migration explain the Hispanic Paradox? A comparative analysis of Mexicans in the U.S. and Mexico. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(3), 624-635. DOI: 10.1007/s10903-012-9646-y. [ Links ]

Bourhis, R. Y., Barrette, G., El-Geledi, S., & Schmidt, R. (2009). Acculturation orientations and social relations between immigrant and host community members in California. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(3), 443-467. [ Links ]

Bourhis, R. Y., Moise, L. C., Perreault, S., & Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32(6), 369-386. [ Links ]

Brasil (1980). Lei nº 6.815, de 19 de agosto de 1980. Define a situação jurídica do estrangeiro no Brasil, cria o Conselho Nacional de Imigração. Brasília: Diário Oficial de União, 21 de agosto de 1980. [ Links ]

Brasil (2012). Resolução Normativa nº 97, de 12 de janeiro de 2012. Dispõe sobre a concessão do visto permanente previsto do art. 16 da Lei n° 6.815, de 19 de agosto de 1980, a nacionais do Haiti (pp. 59). Brasília: Diário Oficial da União, 13 de janeiro de 2012. [ Links ]

Breslau, J., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Borges, G., Kendler, K. S., Su, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-born descendants: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(3), 189-195. DOI: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243779.35541.c6. [ Links ]

Fouchier, C. D. (2013). Évaluation d’un protocole psychotérapeutique associant la psychoéducation, la relaxation et l’EMDR dans la prise en charge des réfugiés victimes de torture d’Afrique Centrale et de l’ouest. Université Paris 8.

Drogendijk, A. N., Van Der Velden, P. G., & Kleber, R. J. (2012). Acculturation and post-disaster mental health problems among affected and non-affected immigrants: A comparative study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 138(3), 485-489. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.037. [ Links ]

Fassaert, T., De Wit, M. a S., Tuinebreijer, W. C., Knipscheer, J. W., Verhoeff, A. P., Beekman, A. T. F., & Dekker, J. (2011). Acculturation and psychological distress among non-Western Muslim migrants-a population-based survey. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(2), 132-143. DOI: 10.1177/0020764009103647.

Gonidakis, F., Korakakis, P., Ploumpidis, D., Karapavlou, D.-A., Rogakou, E., & Madianos, M. G. (2011). The relationship between acculturation factors and symptoms of depression: A cross-sectional study with immigrants living in Athens. Transcultural Psychiatry, 48(4), 437-454. DOI: 10.1177/1363461511408493. [ Links ]

Handerson, J. (2015). Diaspora. Sentidos sociais e mobilidades haitianas. Horizontes Antropológicos, 21(43), 51-78. DOI: 10.1590/S0104-71832015000100003. [ Links ]

Hilario, C. T., Vo, D. X., Johnson, J. L., & Saewyc, E. M. (2014). Acculturation, Gender, and Mental Health of Southeast Asian Immigrant Youth in Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(6), 1121-1129. DOI: 10.1007/s10903-014-9978-x. [ Links ]

Lau, A. S., Tsai, W., Shih, J., Liu, L. L., Hwang, W.-C., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2013). The immigrant paradox among Asian American women: are disparities in the burden of depression and anxiety paradoxical or explicable? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 901-11. DOI: 10.1037/a0032105. [ Links ]

Liddell, B. J., Chey, T., Silove, D., Phan, T. T. B., Giao, N. M., & Steel, Z. (2013). Patterns of risk for anxiety-depression amongst Vietnamese-immigrants: a comparison with source and host populations. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 329. DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-329. [ Links ]

Lindert, J., Ehrenstein, O. S. von, Priebe, S., Mielck, A., & Brähler, E. (2009). Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 69(2), 246-257. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032.

Moïse, L. A., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1996). Identité sociale, discrimination et modèles d’acculturation chez des Antillais à Montreal. Communication présentée au 6e Congrès International de l’Association pour la Recherche Interculturelle (ARIC), Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Mollica, R. F., Wyshak, G., de Marneffe, D., Khuon, F., & Lavelle, J. (1987). Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: A screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(4), 497-500. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.144.4.497. [ Links ]

Morawa, E., & Erim, Y. (2014). acculturation and depressive symptoms among turkish immigrants in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(9), 9503-9521. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph110909503. [ Links ]

Navas, M., García, M. C., Sánchez, J., Rojas, A. J., Pumares, P., & Fernández, J. S. (2005). Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): New contributions with regard to the study of acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(1), 21-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.04.001. [ Links ]

Navas, M., Rojas, A. J., García, M., & Pumares, P. (2007). Acculturation strategies and attitudes according to the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): The perspectives of natives versus immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(1), 67-86. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.08.002. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration (2015). Dados do SINCRE sobre as migrações haitianas no Brasil. Available from: https://www.iom.int/. Access on 10 Jan. 2016. [ Links ]

Ramelli, M., Florack, A., Kosic, A., & Rohmann, A. (2013). Being prepared for acculturation: On the importance of the first months after immigrants enter a new culture. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 363-373. DOI: 10.1080/00207594.2012.656129. [ Links ]

Rollsing, C., & Trezzi, H. (2014). Novos imigrantes mudam o cenário do Rio Grande do Sul. Zero Hora. Retrieved from http://zh.clicrbs.com.br/rs/noticias/noticia/2014/08/novos-imigrantes-mudam-o-cenario-do-rio-grande-do-sul-4576728.html [ Links ]

Sam, D. L., & Berry, J. W. (2010). Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 472-481. DOI: 10.1177/1745691610373075. [ Links ]

Virta, E., Sam, D. L., & Westin, C. (2004). Adolescents with Turkish background in Norway and Sweden: A comparative study of their psychological adaptation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 45(1), 15-25. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00374.x. [ Links ]

Yoon, E., Chang, C.-T., Kim, S., Clawson, A., Cleary, S. E., Hansen, M., Gomes, A. M. (2013). A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 15-30. DOI: 10.1037/a0030652. [ Links ]

Zamberlam, J., Corso, G., Cimadon, J.M., Bocchi, L. (2014). Os novos rostos da imigração no Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre: Solidus. [ Links ]

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support and funding by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil). Furthermore, the authors are thankful for the time and support provided by the Centro Ítalo Brasileiro de Apoio e Instrução aos Imigrantes (CIBAI).

Recebido em 28 de Fevereiro de 2018/ Aceite em 31 de Maio de 2019