Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.20 no.3 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15309/19psd200316

Portuguese colonial war veterans’ mental health: a systematic review

A saúde mental dos ex-combatentes da guerra colonial portuguesa: uma revisão sistemática

Ângela Maia1 & Diogo Morgado1

1Centro de Investigação em Psicologia da Universidade do Minho, Departamento de Psicologia Aplicada, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, angelam@psi.uminho.pt, b8199@psi.uminho.pt

ABSTRACT

Forty-five years have passed since the end of the Portuguese colonial war, however, no systematic review was conducted with the purpose to present the main themes and synthesize the key findings regarding veterans’ mental health. This review aims to fill this gap. This review followed the steps outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Relevant articles were identified through electronic databases, without limits on study design or publication year. Searches were supplemented with bibliographic reviews and consultation with experts. Eligible studies were assessed for their methodological quality. The search yielded 215 titles; 26 met inclusion criteria. Veterans’ mental health literature crosses over several domains, including, prevalence, risk factors, functional impairment, interventions, and factors related to recovery from Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. All studies were cross-sectional and conducted in Portugal. Results indicate that veterans presented a high degree of family, occupational and medical functional impairment, with reports of high prevalence of PTSD and comorbidities. Veterans with PTSD and without PTSD verbalized different trajectories after the war. Risk and protective factors associated with mental disorders were found. Behavioral therapy and virtual reality expose therapy may help veterans’ mental health. The literature lacks interventional and longitudinal designs. Understudied content areas include, for example, satisfaction with health care use, or the effect of aging on veterans’ mental health.

Keywords: Portuguese colonial war, veterans, mental health, systematic review

RESUMO

O fim da guerra colonial portuguesa ocorreu há quarenta e cinco anos, contudo, nenhuma revisão sistemática foi realizada com o intuito de apresentar os principais temas e resultados relacionados com a saúde mental dos ex-combatentes. Esta revisão visa responder a esta lacuna. Esta revisão seguiu os passos delineados pela Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Artigos relevantes foram identificados através de bases de dados eletrónicas, sem limites no design do estudo ou ano de publicação. As pesquisas foram complementadas com revisões bibliográficas e consulta com especialistas. Foi avalidada a qualidade metodológica dos estudos elegíveis. Foram identificados 215 títulos; 26 cumpriram critérios de inclusão. A literatura da saúde mental dos ex-combatentes apresenta vários temas, incluindo, prevalência, fatores de risco, comprometimento funcional, intervenções, e fatores relacionados com a recuperação do diagnóstico de perturbação pós-stress traumático (PPST). Todos os estudos foram transversais e realizados em Portugal. Os resultados indicam que os ex-combatentes apresentaram um alto nível de disfuncionamento familiar, ocupacional e médico, com relatos de alta prevalência de PPST e comorbilidades. Ex-combatentes com e sem PPST verbalizaram diferentes trajetórias após a guerra. Foram encontrados fatores de risco e de proteção associados a perturbações mentais. A terapia comportamental e a terapia de exposição a realidade virtual podem melhorar a saúde mental dos ex-combatentes. A literatura carece de designs intervencionais e longitudinais. Temas pouco estudados incluem, por exemplo, a satisfação com a utilização dos cuidados de saúde, ou o efeito da idade avançada na saúde mental dos ex-combatentes.

Palavras-chave: guerra colonial Portuguesa, ex-combatentes; saúde mental, revisão sistemática

The Portuguese Colonial War (PCW) left deep marks in the lives of thousands of veterans. Between 1961 and 1974, about one million Portuguese soldiers were involuntarily mobilized to three war theaters in order to maintain the former Portuguese colonies (Maia, McIntyre, Pereira, & Fernandes, 2006). Sharing the same characteristics as the Vietnam war (i.e., guerrilla warfare), many young adult soldiers were exposed to several high intensity war stressors, including, witnessing comrades being killed, transport enemy or comrade corpses, being victim of mines, or commit violent acts against enemies or civilians (Maia, McIntyre, Pereira, & Ribeiro, 2011). Consequently, 40.000 were injured and 10.000 lost their lives (Maia et al., 2006). Of those who survived, many reported psychological chronic conditions, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression or substance abuse, which, in turn, had a profound effect on several aspects of veterans’ lives (occupational, medical, marital relationship) (e.g., Albuquerque, Fernandes, Saraiva, & Lopes, 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994; Ferrajão, 2017). Despite these consequences, efforts were made in Portugal to “forget” the repercussions of the PCW, given that the majority of Portuguese society considered the PCW an immoral and unjust war, thus neglecting, and, consequently, creating a feeling of social discrimination in PCW veterans (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014; Maia et al., 2006).

Several systematic reviews presented data about veteran’ mental health who fought in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan (Bean-Mayberry et al., 2011; Runnals et al., 2014). However, no systematic review, to our knowledge, was conducted with the purpose to synthesize the key findings of PCW veterans’ mental health.

Considering this gap in the literature, this review places a major focus on PCW veterans’ mental health, by presenting the main mental health themes and synthesizing key findings. The scope of this review was guided by the research question: “What do we know about veterans’ mental health and what have been done considering that information?”

Method

Search Strategy

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). Relevant articles were identified through different electronic databases: Web of Science/Medline, PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SciELO and ScienceDirect, in March 2019. With the help of MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings), the following search equation was selected: ("Portuguese Colonial War" OR "Ultramar War") AND ("Veteran* [MESH]" OR "former combatants") AND ("Veterans Health [MESH]" OR "Mental Health [MESH]" OR "Mental disorders [MESH]" OR "Mental Illness" OR "Psychopathology" OR "Posttraumatic stress [MESH]" OR "Depression [MESH]" OR "Anxiety"). The search strategy was conducted without limits on study design or publication year. However, we restricted the search strategy only to English and Portuguese language. We also conducted searches on Google Scholar for the inclusion of gray literature (i.e., master’s and doctoral theses, and research reports). Database searches were supplemented by a bibliographic review of identified articles, as well as consultation with subject matter experts.

Eligibility criteriaInclusion criteria were: 1) Empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals, unpublished master’s or doctoral theses, and research reports; 2) samples comprising only PCW veterans; and 3) focus on mental health topics. Conference articles with superficial information, opinion articles, posters, chapters of books, reviews, empirical studies without PCW veteran samples, and studies that did not assess any mental health topic were excluded.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (AM and DM), independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts. All disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Quality Appraisal

The quality appraisal of the studies was independently conducted by two reviewers (AM and DM). We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018) for the assessment of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. Given that Hong et al. (2018) discourage the calculation of an overall score, both reviewers provided a more detailed presentation of the ratings of each criterion from the included studies. There was great agreement among the reviewers, however when disagreements arose, those were discussed until a consensus was reached. Studies were not excluded by quality appraisal.

Data Extraction

Data from each study was independently extracted by one reviewer (DM), using a standardized data extraction sheet in Excel. Subsequently, a second reviewer verified the extracted data for accuracy. All disagreements were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. The information extracted was: 1) author's name and year of publication; 2) sample size; 3) design, 4) procedures and method; and 5) main results.

Data Synthesis

Included articles were grouped into five topical categories: 1) Prevalence of mental disorders, 2) Risk factors, 3) Related functional impairment, 4) Interventions, and 5) Different trajectories and factors related to recovery. These categories are organized in a discrete and nonoverlapping manner, according to the main identified themes from included studies. Key findings are described in the Results section.

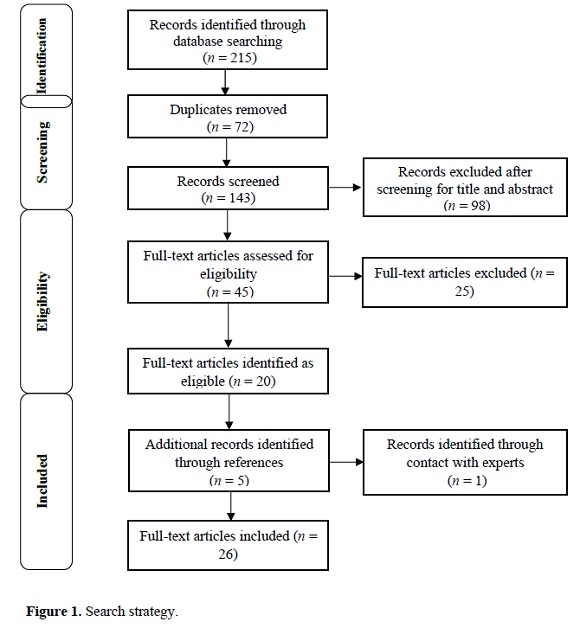

ResultsYield

We initially identified 215 studies (Figure 1). After the duplicates were removed (n = 72), the titles and abstracts were screened. After the screening process (n = 143), 98 studies were excluded. Forty-five underwent full-text assessment, and 25 were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were: 1) content criteria not met (n = 5); 2) unclear study design (n = 4); 3) chapter of books without empirical studies (n = 4); 4) duplicate data (n = 3); 5) unpublished master`s thesis with very small sample sizes (n < 8) (n = 3); 6) not have access to full-text (even after request) (n = 2); 7) scientific presentations (i.e., posters) (n = 1) and 8) absence of PCW veteran samples (n = 3). References of eligible studies were manually analyzed, resulting in five additional studies. One study was identified through contact with subject matter experts (Figure 1). The 26 included articles underwent data abstraction and categorization into the five topical categories: 1) Prevalence of mental disorders (n = 15); 2) risk factors (n = 11); 3) related functional impairment (n = 17); 4) interventions (n = 2), and 5) factors related to recovery (n = 6).

Description of Evidence

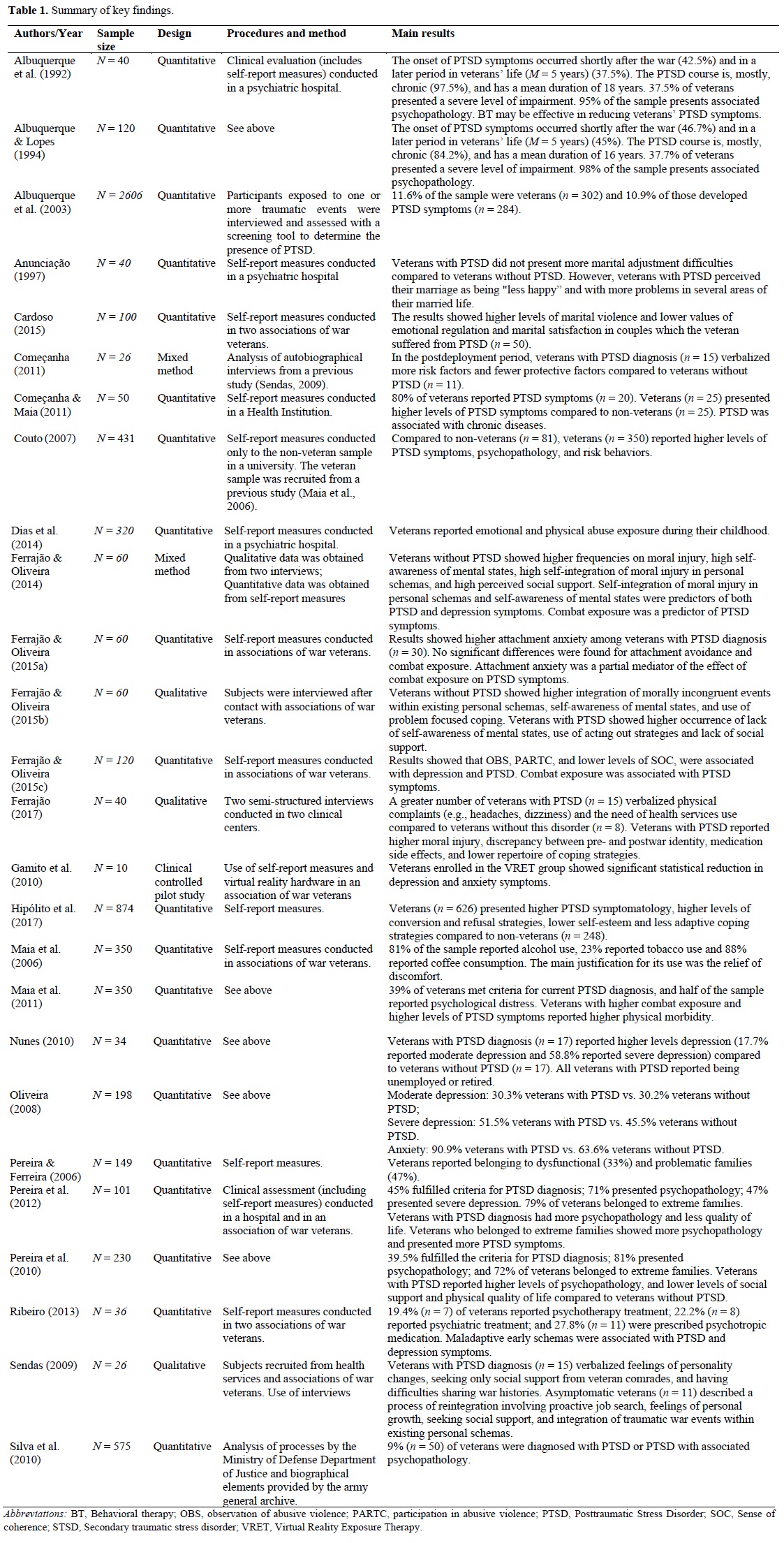

All studies presented a cross-sectional design, and were all conducted in Portugal. Nine studies were written in English and 17 were written in Portuguese. From the included studies, 17 were published peer-reviewed articles, six were unpublished master`s theses, one was an unpublished doctoral thesis, and two were research reports. The veterans were recruited mostly through Veteran's Associations, Clinical Centers, Hospitals, Health Institutions, and Military Hospital Boards. In addition to veteran samples, two studies included samples of veterans’ wives (Cardoso, 2015; Pereira & Ferreira, 2006); one included samples of first-born sons (Dias, Sales, Cardoso, & Kleber, 2014), and one included both groups (Oliveira, 2008). Similarly, three studies included non-veteran samples (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Couto, 2007; Hipólito et al., 2017), and one included a representative sample of the adult Portuguese population (Albuquerque, Soares, Jesus, & Alves, 2003). The majority of studies were published between 2003 and 2017, with only three studies being published in the 1990’s (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994; Anunciação, 1997). Three studies chose the qualitative method, conducting individual semi-structured interviews, and using either Thematic and Categorical Analysis (Ferrajão, 2017; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2015b), or Grounded Analysis (Sendas, 2009). Two studies chose the mixed method, conducting semi-structured interviews and administered self-report measures (Começanha, 2011; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014). One study consisted of a quantitative clinical controlled pilot study, using self-report measures and virtual reality hardware for the assessment of virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) (Gamito et al., 2010). One descriptive study used an alternative method using processes developed by the Portuguese Ministry of National Defense, and biographical elements provided by the Army General Archive (Silva et al., 2010). The remaining studies chose the quantitative non-randomized (n = 14) or descriptive method (n = 5), prioritizing the use of self-report measures. Characteristics and main results are summarized in Table 1.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

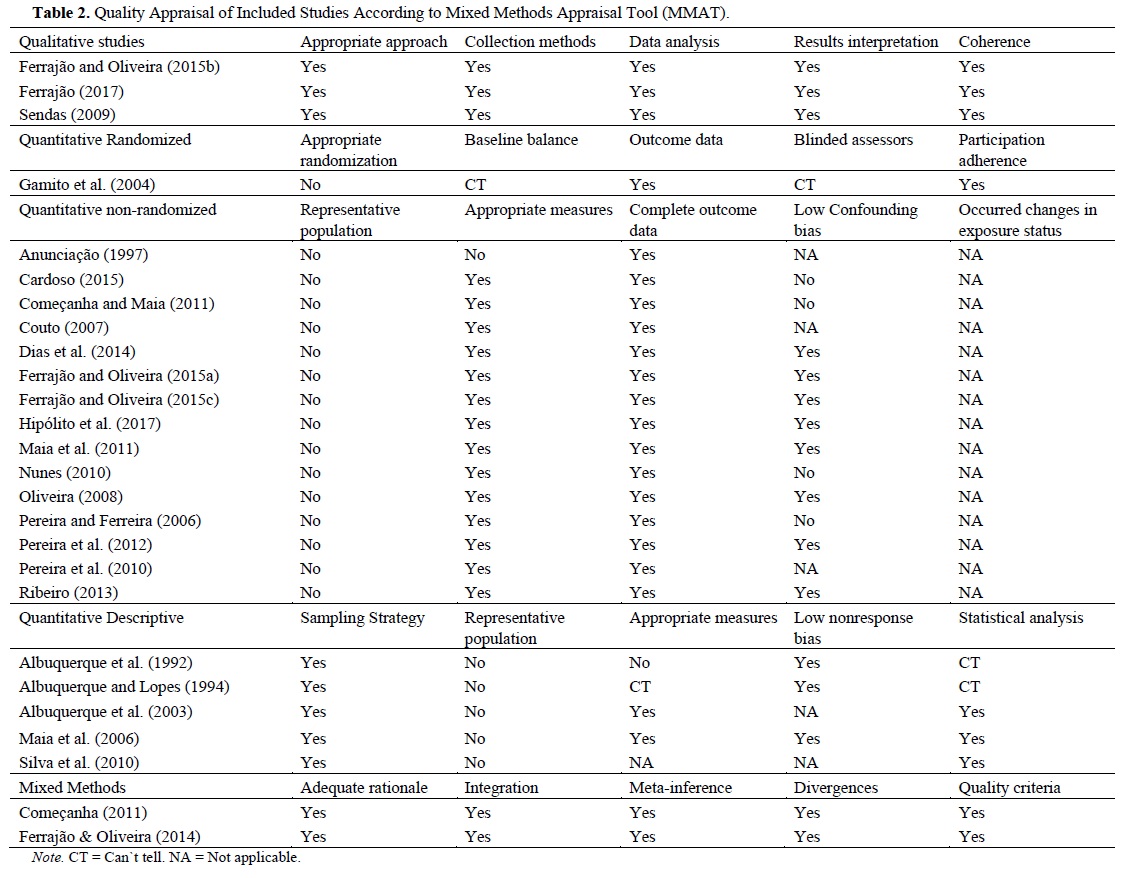

Quality Assessment

Quality appraisal of each criterion of the included studies is presented in detail in Table 2. The main sources of bias were all studies presenting cross-sectional designs, the lack of representativeness due to convenience sampling, the lack of control of potential confounders, and the use of self-report measures without detailed information (e.g., lack of psychometric properties, type of response to the item - Likert or dichotomous response).

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

Prevalence of mental disorders

PTSD was present in all included studies. Overall, the prevalence of PTSD varied significantly among studies. Some studies presented a minimum prevalence rate ranging between 9% and 10.9% (Albuquerque, 2003; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2015c; Silva et al., 2010); others had an medium prevalence rate ranging between 39% and 45% (Maia et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2010), and, finally, one study had a 80% prevalence rate (Começanha & Maia, 2011). Despite this variation, the prevalence of PTSD reveals to be superior compared to non-veteran samples (Albuquerque, 2003; Couto, 2007; Hipólito et al., 2017). The onset of PTSD symptoms occurred more predominantly shortly after the war (ranging between 42.5% and 46.7%) or later in veterans’ life (M = 5 years) (ranging between 37.5% and 45%) (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994). However, several studies showed that the PTSD course was, mostly, chronic (ranging between 84.2% and 97.5%) (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994), and over a period of ten years (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014).

Veterans presented other mental disorders, with high prevalence rates, such as, moderate depression (ranging from 17.7% to 30.3%) (Nunes, 2010; Oliveira, 2008), and severe depression, (ranging from 47% to 58.8%) (Nunes, 2010; Oliveira, 2008; Pereira et al., 2012); anxiety (90.9%) (Oliveira, 2008), psychopathology (ranging from 49% to 80.9%) (Maia et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2010), and addiction to alcohol and drugs (ranging from 20.8% to 81%) (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Albuquerque & Lopes, 1994; Maia et al., 2006). Compared with non-veteran samples, the results showed that veterans had higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Couto, 2007; Hipólito et al., 2017), psychopathology, and a higher index of risk behaviors (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, drug abuse) (Couto, 2007).

Risk Factors

Combat exposure (CES) was one of the main predictors of veterans’ PTSD symptoms, depression, and psychopathology (Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014, 2015a, 2015c; Maia et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2010). Similarly, observation of abusive violence (OBS) and participation in abusive violence (PARTC) also showed a significant association with depression and PTSD diagnosis (Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2015c).

History of childhood trauma may also explain the development of mental health problems, specifically PTSD symptoms (Dias et al., 2014; Maia et al., 2011). For example, Dias et al. (2014) found that veterans with PTSD (n = 31) had higher levels of emotional and physical abuse compared to veterans without PTSD (n = 56) and to non-veterans (n = 30).

Studies also showed other significant risk factors of PTSD and depression symptoms, including self-integration of moral injury in personal schemas and self-awareness of mental states (Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014), attachment anxiety (Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2015a), maladaptive early schemas (Ribeiro, 2013), and extreme families (i.e., families presenting high levels of conflict) (Pereira, Pedras, & Lopes, 2012).

Related functional impairment

According to Albuquerque et al. (1992) and Albuquerque and Lopes (1994), over 80% of veterans presented a moderate or severe degree of family, occupational and medical functional impairment.

Regarding family functional impairment, the majority of veterans belonged to extreme (ranging between 71.1% and 79%) (Pereira et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2010), dysfunctional (33%) and problematic families (47%) (Pereira & Ferreira, 2006). When compared veterans with and without PTSD diagnosis, the results showed higher levels of marital violence and lower values of emotional regulation and marital satisfaction in couples with PTSD (Anunciação, 1997; Cardoso, 2015). Regarding marital violence, Maia et al. (2006) found that 37% of veterans (N = 350) reported at least one type of violent behavior (e.g., insulting, slapping) toward their wives in an attempt to reduce their discomfort. Furthermore, Couto (2007) found that veterans (n = 350) presented a higher rate of marital violence when compared to non-veterans (n = 81).

Veterans presented also occupational impairments. Overall, the unemployment rate varied between 9.1% and 42% (Maia et al., 2006; Pereira, Pedras, & Lopes, 2012; Sendas, 2009), and the retirement rate revealed to be even higher, in which some studies showed a rate higher than 90% (Cardoso, 2015; Nunes, 2010).

Regarding medical impairment, studies showed a significant relationship between PTSD symptoms and veterans’ physical health problems (e.g., fatigue, cardiovascular disease) (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Maia et al., 2011). Consequently, Couto (2007) found that veterans (n = 350) had a higher rate of physical health problems compared to non-veterans (n = 81).

Interventions

Albuquerque et al. (1992) conducted a behavioral therapy (BT) in order to assess its effectiveness in reducing PTSD symptoms and comorbidities in a total sample of 40 veterans. Given the heavy emotional load of the treatment, only 25 (62.5%) completed the full procedure. Results indicated that BT was effective in reducing veterans’ PTSD symptoms, however, it revealed not to be effective in reducing depression or anxiety symptoms.

As an alternative procedure to reduce PTSD symptoms, Gamito et al. (2010) assessed the effectiveness of virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) in a sample of 10 veterans diagnosed with PTSD. This sample was randomly assigned into three groups: VRET group (n = 5), exposure in imagination (EI) (n = 2), and waiting list (WL) (n = 3). Results indicated that the VRET group showed a decrease on PTSD and psychopathological symptoms, when compared to EI and WL groups. Thus, the authors concluded that VRET could be a good alternative procedure to reduce veterans’ mental health problems.

In addition to these interventional studies, other studies indicated that a significant percentage of veterans were in psychological/ psychiatric treatments (Cardoso, 2015; Maia et al., 2011; Ribeiro, 2013), and were prescribed medication (e.g., antidepressants, anxiolytics) (Albuquerque et al., 1992; Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014, Ribeiro, 2013) to reduce traumatic symptoms and comorbidities.

Different trajectories and factors related to recovery

Veterans with and without PTSD reported different trajectories after the post-deployment period (Começanha, 2011; Nunes, 2010; Sendas, 2009). According to Sendas (2009), veterans with PTSD diagnosis (n = 15) verbalized feelings of personality changes, seeking only social support from veteran comrades, and difficulties sharing war histories due to fear of rejection, misunderstanding, and protection against re-experience of war memories, which, consequently, resulted in higher discrepancy between preand postwar identity and societal alienation. Conversely, PTSD asymptomatic veterans (n = 11) described a process of reintegration involving proactive job search, family relationships and pre-war friends, feelings of personal growth, social support, and integration of traumatic war events within existing personal schemas, resulting in higher identity coherence and continuity. In a later study with this sample, Começanha (2011) confirmed the existence of more risk factors and fewer protective factors in veterans with PTSD after the postdeployment period.

These protective factors seem to be also related to recovery from chronic PTSD. In order to explore the factors to which veterans attributed their recovery from PTSD, Ferrajão and Oliveira (2014, 2015b) conducted two studies with the same total sample of veterans (N = 60), divided into two groups: one included 30 veterans diagnosed with a current PTSD diagnosis (unrecovered); and the other included 30 veterans who were previously diagnosed with PTSD but recovered from this condition (recovered). Results showed that recovered veterans reported higher self-awareness of mental states (i.e., the capacity to perceive and understand oneself and others in terms of mental states) (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002); higher self-integration of moral injury in personal schemas (e.g., report of feelings of endurance), higher perceived social support, and use of problem focused coping. Conversely, unrecovered veterans showed higher inability to understand their own behavior, feelings of weakness and shame, higher discrepancy between preand postwar identity, higher presence of conflictual relationships, and higher use of acting out strategies (e.g., violent acts towards others) (Ferrajão & Oliveira, 2014; 2015b). Regarding moral injury (i.e., perpetration, witness, or failure to prevent acts that transgress internalized moral beliefs and expectations) (Litz et al., 2009), Ferrajão and Oliveira (2014) indicated that there were no significant differences between these two groups. However, in another study with a total sample of 40 veterans, unrecovered participants (n = 20) reported higher moral injury (Ferrajão, 2017), thus revealing an incongruity regarding this variable.

Discussion

Forty-five years have passed since the end of the PCW. However, the research on PCW veterans’ mental health has begun to grow only in the past 13 years. Thus, contrary to the international literature (e.g., Williamson, Stevelink, Greenberg, & Greenberg, 2018), it is not surprising the lack of a systematic review on PCW veterans’ mental health. This review aims to fill this gap by presenting the key themes and findings on PCW veterans’ mental health research.

The studies that we reviewed provided relevant information about veterans’ mental health, including: 1) the prevalence of PTSD symptoms and comorbid conditions; 2) risk factors related to mental disorders; 3) related medical, occupational, and, family functional impairment; 4) interventions; and 5) different trajectories and factors related to recovery from PTSD diagnosis. Most of these themes were consistent with prior reviews of other veteran samples, as well as key limitations, such as the scarcity of interventional and longitudinal designs (Runnals et al., 2014).

Explicit within this review is that combat exposure and other risk factors (e.g., history of childhood trauma, attachment anxiety, low self-awareness of mental states) may have contributed to the emergence and severity of several mental health problems. Results showed that veterans reported significant, although different prevalence rates of PTSD symptoms (ranging between 9% and 80%), and comorbidities, including depression, psychopathology, and substance abuse. One possible explanation for the different rates of veterans’ PTSD symptoms may be due to different study sample sizes, in which the larger the study sample size, the lower the PTSD prevalence rate. For example, Começanha and Maia (2011) found an 80% prevalence rate of symptoms compatible with PTSD diagnosis in a sub-sample of 25 veterans, whereas Silva et al. (2010) found that only 50 (9%) veterans had a PTSD diagnosis, from a total sample of 575. Another plausible explanation is the fact that studies that presented a higher PTSD prevalence rate recruited clinical samples (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Maia et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2012; Pereira et al., 2010) from hospitals, clinical centers, or Veterans Associations. Despite these possible limitations, included studies with non-veteran samples showed that veterans reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Couto, 2007), psychopathology, and a higher index of risk behaviors (Couto, 2007). However, some caution is needed regarding the interpretation of these results, given the scarcity of studies that included non-veteran samples, which presented small sample sizes.

Veterans presented also a severe degree of medical, occupational, and family functional impairment (e.g., Albuquerque et al., 1994). The rate of unemployment and retirement before the age of 65 was high in this population (e.g., Cardoso, 2015; Maia et al., 2006), and a significant relationship was found between PTSD symptoms and physical health problems (Começanha & Maia, 2011; Maia et al., 2011). Regarding the family functional impairment, we highlight the effect of veterans` PTSD diagnosis on marital violence and marital satisfaction. In fact, veterans reported at least one type of marital violence behavior to reduce discomfort related to the war (Maia et al., 2006). These results may explain the high rates of extreme, dysfunctional and problematic families that veterans belong to (Pereira et al., 2010; Pereira & Ferreira, 2006). The results presented here are consistent with the international literature (Runnals et al., 2014), however, some caution is needed given the scarcity of studies that assess veterans` functional impairment; the preference of cross-sectional designs, and the recruitment of convenient samples. Future studies may address this issue by conducting a longitudinal design study, with larger sample sizes.

BT and VRET may be efficient in reducing veterans’ PTSD symptoms (Albuquerque et al., 1994; Gamito et al., 2010). However, several limitations should be addressed regarding these results, such as the high dropout rate in the study conducted by Albuquerque et al. (1992), the participation of very small sample sizes, and the absence of a follow-up assessment after the last session. In addition, we did not find other studies that replicated these interventions, thus it is not possible to determine the consistency of these results. Future studies may try to replicate these findings by recruiting larger sample sizes.

Despite the potential impact of PCW on veterans’ mental health, not all veterans presented a pathogenic pathway. According to Sendas (2009), asymptomatic veterans reported, for example, feelings of personal growth, seeking social support and higher identity coherence and continuity. These protective factors seem also be related to recovery from chronic PTSD diagnosis. According to Ferrajão and Oliveira (2014, 2015b), recovered veterans verbalized higher self-awareness of mental states, self-integration of moral injury in personal schemas, seeking social support, and use of problem focused coping. However, these cross-sectional design studies, with very small sample sizes, were the only ones who presented these results, thus compromising the generalization of the data. Given the interesting results of these studies, it would be important to replicate them in future longitudinal design studies with larger sample sizes.

In addition to the need of longitudinal studies, we identified knowledge gaps in several content areas. Understudied topics include the prevalence and treatment of other serious mental illness (e.g., anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), and assessment of risk and protective factors associated with these mental disorders. Such studies would present important findings for future research, as well as the development of prevention and treatment interventions. Similarly, additional studies are needed to assess the impact of these comorbid mental health conditions on veterans’ functional impairment (e.g., medical, interpersonal, occupational, social). Such studies would broaden the knowledge about the potential impact of PCW on veterans` lives and their families, and identify potential preventative and treatment interventions to mitigate reintegration problems. Unlike the international literature (Runnals et al., 2014), we also did not find data regarding veterans` satisfaction with mental health care. Indeed, only one study was found that indicated that veterans reported a higher use of mental health services (e.g., public hospital, health center), compared with non-veterans (Começanha & Maia, 2011). This data would be important for the understanding of the best practices regarding the specific needs of this population. Another forgotten topic in the literature is the potential risk factor of aging on veterans` mental health. Given that this population is at a relatively advanced age of life, future studies should address this issue by assessing the impact of this potential risk factor on veterans` mental health condition. Finally, no included study presented a representative sample of PCW veterans, thus compromising the generalization of the results. However, given the difficulty in accessing up-to-date and official databases (Maia et al., 2006), sample collection in psychiatric hospitals or in veterans’ associations appeared to be the most appropriate method for establishing contact with this population.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths and limitations of this review merit attention. The inclusion of English and Portuguese language peer-reviewed studies, and unpublished gray literature, without time restrictions reveals to be a possible strength of the current review, since prevents potential publication bias. However, the inclusion of data from unpublished studies can itself be a source of bias, given the absence of peer-review editors, and the possibility of including studies with a lower methodological quality compared with published studies. Similarly, efforts were made to capture all relevant articles; however, it is possible that articles were overlooked. Furthermore, this review does not present all relevant data, given that it did not included two possible eligible studies due to the absence of a response from the respective authors. Despite these limitations, efforts were undertaken to mitigate data omission by conducting bibliography reviews from the eligible studies, as well as consulting with experts. Finally, the key findings from the current review may not be representative of all veterans, given the preference of convenience sampling and the inclusion of small sample sizes from the included studies.

REFERENCES

Albuquerque, A., Fernandes, A., Saraiva, E., & Lopes, F. (1992). Distúrbios pós-traumáticos do stress em ex-combatentes da guerra colonial [Post-traumatic stress disorder in former colonial war veterans]. Revista de Psicologia Militar, 399-407.

Albuquerque, A., & Lopes, F. (1994). Características de um grupo de 120 ex-combatentes da guerra colonial vitímas de «stress de guerra» [Characteristics of a group of 120 former colonial war veterans victims of «war stress»]. Vértice, 58, 28-32.

Albuquerque, A., Soares, C., Jesus, P. M., & Alves, C. (2003). Perturbação pós-traumática do stress (PTSD): Avaliação da taxa de ocorrência na população adulta portuguesa [Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Assessment of occurrence rate in the portuguese adult population]. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 16, 309-20.

Antonovsky, A. (1998). The structure and properties of the Sense of Coherence scale. In H. I. McCubbin, E. A. Thompson, A. I. Thompson, & J. E. Fromer (Eds.), Stress, coping, and health in families: Sense of coherence and resiliency (pp. 2140). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Anunciação, C. (1997). Ajustamento marital em ex-combatentes da Guerra Colonial com e sem perturbação pós-stress traumático [Marital adjustment in Colonial War veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder]. Análise Psicológica, 15, 595-604.

Bean-Mayberry, B., Yano, E. M., Washington, D. L., Goldzweig, C., Batuman, F., Huang, C., … & Shekelle, P. G. (2011). Systematic review of women veterans’ health: Update on successes and gaps. Women’s Health Issues, 21, S84-S97. DOI: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.022. [ Links ]

Blodgett, J. C., Avoundjian, T., Finlay, A. K., Rosenthal, J., Asch, S. M., Maisel, N. C., & Midboe, A. M. (2015). Prevalence of mental health disorders among justice-involved veterans. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37, 163-176. DOI: 10.1093/epirev/mxu003. [ Links ]

Cardoso, R. G. (2015). PPST e conjugalidade: Regulação emocional, violência e satisfação conjugal em casais com historial de exposição à Guerra Colonial [PTSD and Conjugality: Emotional regulation, violence and marital satisfaction in couples with a history of exposure to the Colonial War]. (Master`s thesis, Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal). Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/61019318.pdf

Começanha, A. R. S. (2011). Percursos individuais face ao potencial trauma em ex-combatentes da guerra colonial: Uma comparação entre a patogénese e a salutogénese [Individual pathways to potential trauma in colonial war veterans: A comparison between pathogenesis and salutogenesis]. (Master’s thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal). Retrieved from https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/15849/1/Ana%20Rita%20Silva%20Come%C3%A7anha.pdf

Começanha, R., & Maia, A. (2011). Determinantes da utilização de serviços de saúde em ex-combatentes da Guerra Colonial Portuguesa: Estresse pós-traumático, neuroticismo e apoio social [Determinants of use of health services in Portuguese Colonial War veterans: Posttraumatic stress, neuroticism and social support]. Contextos Clínicos, 4, 123-131. DOI: 10.4013/ctc.2011.42.06.

Couto, M. J. (2007). Exposição a trauma e caracterização do ajustamento psicológico, de saúde, familiar e laboral de uma amostra de homens portugueses: Um estudo comparativo entre ex-combatentes da guerra colonial e um grupo da mesma idade sem essa experiência [Trauma exposure and the characterization of psychological adjustment, health, family and work indicators in a sample of portuguese men: A comparative study among veterans of the colonial war and their non-veteran cohorts] (Unpublished master thesis) Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2013). CASP checklists. Available at: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/15849/1/Ana%20Rita%20Silva%20Come%C3%A7anha.pdf (Accessed 20 March, 2019). [ Links ]

Dias, A., Sales, L., Cardoso, R. M., & Kleber, R. (2014). Childhood maltreatment in adult offspring of Portuguese war veterans with and without PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, 20198. DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.20198. [ Links ]

Ferrajão, P. C., & Oliveira, R. A. (2014). Self-awareness of mental states, self-integration of personal schemas, perceived social support, posttraumatic and depression levels, and moral injury: A mixed-method study among Portuguese war veterans. Traumatology, 20, 277-285. DOI: 10.1037/trm0000016. [ Links ]

Ferrajão, P. C., & Oliveira, R. A. (2015a). Attachment patterns as mediators of the link between combat exposure and posttraumatic symptoms: A study among Portuguese war veterans. Military Psychology, 27, 185-195. DOI: 10.1037/mil0000075.

Ferrajão, P. C., & Oliveira, R. A. (2015b). From self-integration in personal schemas of morally experiences to self-awareness of mental states: A qualitative study among a sample of Portuguese war veterans. Traumatology, 21, 22-31. DOI: 10.1037/trm0000019.

Ferrajão, P. C., & Oliveira, R. A. (2015c). The effects of combat exposure, abusive violence, and sense of coherence on PTSD and depression in Portuguese colonial war veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 1-8. DOI: 10.1037/tra0000043.

Ferrajão, P. C. (2017). Pathways between combat stress and physical health among Portuguese war veterans. Qualitative Health Research, 27(11), 1640-1651. DOI: 10.1177/1049732317701404. [ Links ]

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York, NY: Other Press.

Gamito, P., Oliveira, J., Rosa, P., Morais, D., Duarte, N., Oliveira, S., & Saraiva, T. (2010). PTSD elderly war veterans: A clinical controlled pilot study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(1), 43-48. DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0237. [ Links ]

Hipólito, J., Nunes, O., Brites, R., Laneiro, T., Correia, A., & Anunciação, C. (2017). A perturbação de stresse pós-traumático (PTSD) em Portugal: Relação com a estima de si e o coping [Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Portugal: Relation to self-esteem and coping]. Revista Psicologia, 31, 313-319.

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., … Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., ... & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1-e34. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [ Links ]

Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 695-706. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [ Links ]

Maia, A., McIntyre, T., Pereira, G., Fernandes, E. (2006). Por baixo das pústulas da guerra: reflexões sobre um estudo com ex-combatentes da guerra colonial [Beneath the pustules of war: reflections on a study with colonial war veterans]. In Centro de Estudos Lusíadas/ Universidade do Minho, (ed.), A Guerra Colonial (1961-1974) (pp. 11-28). Braga, Portugal

Maia, A., McIntyre, T., Pereira, M. G., & Ribeiro, E. (2011). War exposure and post-traumatic stress as predictors of Portuguese colonial war veterans' physical health. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 24, 309-325. DOI: 10.1080/10615806.2010.521238. [ Links ]

National Institutes of Health (2016). National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (Accessed 20 March, 2019). [ Links ]

Nunes, M. J. M. (2010). A memória autobiográfica na Perturbação de Stress Pós-Traumático: Um estudo com veteranos da guerra colonial Portuguesa [The autobiographical memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A study with Portuguese colonial war veterans]. (Master`s thesis, Instituto Universitário de Psicologia Aplicada, Lisboa, Portugal). Retrieved from http://repositorio.ispa.pt/bitstream/10400.12/4326/1/13265.pdf

Oliveira, S. M. (2008). Traumas da guerra: Traumatização secundária das famílias dos ex-combatentes da guerra colonial com PTSD [War trauma: Secondary trauma of the families of colonial war veterans with PTSD] (Master`s thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal). Retrieved from http://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/803/1/16853_Tese_-_Susana_M_Oliveira.pdf

Pereira, M. G., & Ferreira, J. M. (2006). Variáveis psicossociais e traumatização secundária em mulheres de ex-combatentes da guerra colonial [Psychosocial variables and secondary traumatization in women of former combatants of the colonial war]. In P. J. Costa, C. L. Pires, J. Veloso, & C. L. Pires (Eds.), Stresse pós-traumático: Modelos, abordagens e práticas. Editorial Presença e Adfa.

Pereira, M. G., & Pedras, S. (2011). Vitimização secundária nos filhos adultos de veteranos da Guerra Colonial Portuguesa [Secondary victimization in adult offspring of Portuguese Colonial War veterans]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 24, 702-709.

Pereira, M. G., Pedras, S., & Lopes, C. (2012). Posttraumatic stress, psychological morbidity, pychopathology, family functioning, and quality of life in Portuguese war veterans. Traumatology, 18, 49-58. DOI: 10.1177/1534765611426794. [ Links ]

Pereira, M. G., Pedras, S., Lopes, C., Pereira, M., & Machado, J. C. (2010). Saúde mental, doença, tipo de familía, suporte social e qualidade de vida em veteranos da guerra colonial portuguesa [Mental health, disease, family type, social support and quality of life in Portuguese colonial war veterans]. In Do Diagnóstico à Intervenção em Saúde Mental: II Congresso Internacional da SPESM (pp. 319-330). A Sociedade Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental (ASPESM).

Ribeiro, S. C. M. (2013). A centralidade dos eventos traumáticos em ex-combatentes de guerra [The centrality of traumatic events in war veterans] (Master`s thesis, Instituto Superior de Psicologia Aplicada, Lisboa, Portugal). Retrieved from http://repositorio.ispa.pt/bitstream/10400.12/2783/1/18038.pdf

Runnals, J. J., Garovoy, N., McCutcheon, S. J., Robbins, A. T., Mann-Wrobel, M. C., Elliott, A., ... & Strauss, J. L. (2014). Systematic review of women veterans' mental health. Women's Health Issues, 24, 485-502. DOI: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.012. [ Links ]

Sendas, S. (2009). Elaboração de significado das histórias de vida de ex-combatentes da Guerra Colonial Portuguesa com e sem Perturbação de Stress Pós-Traumático. [Elaboration of the meaning of life stories of veterans of the Portuguese Colonial War with and without Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal.

Silva, J. A., Brito, B., Silva, M. R., Borges, M., Romão, A., Queiroz, S. M., … Santos, A. S. (2010). Feridas de Guerra: (In) justiça silenciada. [Wounds of War: (In) Silenced (In)Justice.]. Retrieved from http://www.aofa.pt/rimp/Relatorio_MDN.pdf

Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A., Greenberg, K., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Prevalence of mental health disorders in elderly US military veterans: A meta-analysis and systematic review. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 534-545. DOI: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.00. [ Links ]

Implications for practice and/or policy

The current review synthesizes the breadth of knowledge available regarding PCW veterans’ mental health. Despite the relevant results found, mainly, from the last 13 years, understudied content areas still exist. Notably, descriptive and observational research examining veterans’ mental health is much more developed compared with research base examining interventional or longitudinal designs. Future studies may advance the field of research regarding veterans’ mental health with the purpose of guiding clinicians and policymakers in methods, which fully address the unique mental health needs of a population that is at a relatively advanced age of life.

Funding

This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (PSI/01662), School of Psychology, University of Minho, and partially supported by the Portuguese Ministry of National Defense under the reference UMINHO/BI/ 173/2018.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Ministry of National Defense for partially funding this project.

Recebido em 08 de Maio de 2019/ Aceite em 31 de Agosto de 2019