Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.20 no.3 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15309/19psd200322

Psychometric analysis of the portuguese version of the family sense of coherence

Análise psicométrica da versão portuguesa do sentido interno de coerência familiar

Francis Carneiro1, Pedro Costa1, & Isabel Leal1

1 William James Center for Research, ISPA - Instituto Universitário, Lisboa, Portugal, fcarneiro@ispa.pt, pcosta@ispa.pt, ileal@ispa.pt

ABSTRACT

Family Sense of Coherence (Antonovsky & Sourami, 1988) is integrated in a Salutogenic model that highlights the family’s strengths and abilities to achieve successful adjustment. FSOC is significantly associated with positive health outcomes, nevertheless, is underresearched. The present study aims to (1) translate and evaluate the psychometric properties of a European Portuguese version of the Family Sense of Coherence (FSOC), and (2) Evaluate the impact of the familiar functioning on children’s psychological adjustment in a Portuguese sample with caregivers of children and adolescences between 10 and 15 years old. A sample of 271 caregivers provided sociodemographic information and completed a Portuguese version of FSOC and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses were performed to evaluate FSOC structure, as well as the internal consistency, composite reliability, convergent-related and discriminant-related validity of the scale scores. Multiple Linear regressions were performed to explore the impact of FSOC on SDQ subscales. Factorial Analysis supported a three-factor solution for a 21-item version of the Portuguese version of FSOC, however without the original item’s organization. New dimensions have been developed: Family Cohesion, Family Resources and Family Communication. FSOC revealed a goodness of fit significantly higher than the original structure model and very good psychometric properties. FSOC revealed significant impact on Prosocial Behaviors and the highest predictor was Family Communication. Results are helpful to researchers that pretend to explore the role of family functioning on psychosocial adjustment. Moreover, FSOC could be very relevant for family researchers and family therapists, since it helps enhancing family well-being.

Keywords: Family sense of coherence, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, psychological adjustment.

RESUMO

O Sentido Interno de Coerência Familiar (Antonovsky & Sourami, 1988) encontra-se integrado no modelo Salutogénico que enfatiza as forças e capacidades das famílias para alcançarem um ajustamento bem-sucedido. O FSOC está significativamente associado a resultados positivos de saúde, contudo é um conceito pouco investigado. O presente estudo tem como objetivos (1) traduzir e avaliar as características psicométricas da versão portuguesa do Sentido Interno de Coerência Familiar (FSOC) e (2) examinar o impacto do funcionamento familiar no ajustamento psicológico infantil numa amostra de cuidadores de crianças com idades compreendias entre os 10 e os 15 anos. A amostra foi constituída por 271 cuidadores que responderam a questões sociodemográficas e preencheram a versão Portuguesa do FSOC e do Questionário de Capacidades e Dificuldades (SDQ). Foi realizada uma análise factorial exploratória e uma análise factorial confirmatória para avaliar a estrutura do FSOC. A consistência interna, a fiabilidade compósita, a validade convergente e a validade discriminante dos scores do FSOC foram também calculadas. Foram realizadas regressões lineares múltiplas para explorar o impacto do FSOC nas subescalas do SDQ. As análises factoriais suportaram uma solução trifactorial da escala com 21 itens. Contudo, a organização dos itens da escala original não se manteve e novas dimensões foram originadas: Coesão Familiar, Recursos Familiares e Comunicação Familiar. A versão portuguesa do FSOC apresentou um bom ajustamento do modelo e boas propriedades psicométricas. O ajustamento do modelo foi significativamente superior ao modelo da estrutura original. O FSOC apresentou um impacto significativo nos Comportamento Pro-sociais e o maior preditor foi a dimensão Comunicação Familiar. Os resultados são pertinentes para os investigadores que pretendam explorar o papel do funcionamento familiar no ajustamento psicológico. Mais, O FSOC pode ser muito relevante para os investigadores e terapeutas familiares uma vez que ajuda a promover o bem-estar da família.

Palavras-chave: Sentido interno de coerência familiar, análise factorial exploratória, análise factorial confirmatória, ajustamento psicológico.

Family sense of coherence (FSOC) is a concept developed from Antonovksy’s theoretical framework. Aaron Antonovsky (1979) originally described the sense of coherence (SOC) as an individual property and latter, with Sourani, has expanded the concept at family level (Antonovsky, 1987; Antonovsky & Sourani, 1988). Salutogenic model of Antonovsky (1979, 1987) is an alternative perspective to the traditional pathogenic model, since it explores the origin of health, instead of focusing in the causes of disease. Conversely to the pathological orientation (‘health vs. disease’ dichotomy), health is perceived as a continuum from health (ease) to disease (dis-ease).

This model highlights individual strengths and capacities to achieve successful adjustment and focuses on why some individuals seem to preserve health, well-being and successfully cope with daily life stressors and tensions (Antonovsky & Sagy, 1986). Salutogenic model has two main key concepts: SOC and generalized resistance resources (GRR). GRR includes biological, material and psychosocial factors that allows individuals to perspective their lives in a consistent, structured and comprehensive way. These factors could be, for instance, self-esteem, healthy behaviors, social support, culture, financial legacy, intelligence, traditions and life perspectives (Lindström & Eriksson, 2006; Söderhamn & Holmgren, 2004). The ability to use these resources is promoted by SOC. SOC is the individual’s ability to maintain orientation, organization and structure, independently from their life events and their severity (Antonovksy, 1979). SOC’s extend literature refers that a high SOC is related to good health (Eriksson & Lindström, 2006).

From a salutogenic familiar perspective, FSOC could be perceived as the family’s ability to deal with stress and challenges. According to Antonovsky and Sourani (1988), FSOC is defined as a family’s cognitive orientations, namely the degree to which a family perceives family life as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful. In this sense, family life perspective and ability to manage successfully a high number of complex stressors could be influenced by appropriate resources that would promote a healthy development. FSOC concept, conversely to SOC, is underresearched, nevertheless according to some researches both variables present a strong positive relationship (Wickens and Greeff, 2005). FSOC can also be included as a family resistance resource against stressors and it could enhance family’s quality of life (Antonovsky & Sourani, 1988; Wickens, & Greeff, 2005). In MacPhee, Lunkenheimer and Riggs’s study (2015), FSOC was associated to suport aqquisition, coping strategies, adaptation to stress and individual well-being. According to Walsh (2016), an elevated FSOC predicts a higher adaption and capacity to cope and manage adverse difficulties. Also, FSOC predicts a higher satisfaction within family and higher community integration.

Although previous literature provides a conceptual frame of FSOC, to the best of our knowledge, few empirical studies have been developed. FSOC has been validated in few countries, namely, Turkey, China, Norway and Sweden (Çeçen, 2007; Moen & Hall-Lord, 2016; Ngai & Ngu, 2011; öderhamn & Holmgren, 2004), however it has not been translated or validated in Portugal.

From an eco-developmental framework, children and adolescent’s psychosocial adjustment depends on a complex interaction of multiple factors and contexts, such as the individual characteristics, family, peer, and community (King et al., 2005; Smith, Faulk, & Sizer, 2016). Understanding how these factors operate has important implications for programs and services with children and families in order to enhance positive developmental outcomes (King et al., 2005).

Although family structure influences children’s developmental outcomes, the most determinant variables for children’s well-being are family processes and functioning (Tasker, 2005; Wu, Hou & Schimmele, 2008). Research highlights the existence of significative associations between family functioning and children’s behavioral functioning (e.g., Kronenberger & Thompson, 1990) and between behavioral functioning and prosocial behavior (e.g., Eisenberg, 1997a). Therefore, family functioning (including, for instance, resource management, monitoring, applying effective discipline, communication, and nonaggressive conflict resolution, etc) can promote and enhance children’s prosocial skills (e.g. Smith, et al., 2016).

Prosocial behavior is an important aspect of social competence. It refers to the degree to which children/adolescence help, support, and empathize with others. Social competence and academic performance, along with emotional and behavioral functioning, are generally considered to be the most important components of children’s adjustment during early and middle childhood (King et al., 2005). Conversely, reduced parental and family interactions and involvement will undermine children’s emotional and social skills, and increase the probability of behavior problems, such as externalizing problems (Wu et al., 2008).

In sum, family functioning is very important to diminished emotional, social and behavioral problems and to promote children’s well-being. Family should support their children to develop self-regulatory skills, which will allow them to regulate and be aware of their own behaviors and emotions through various experiences. Skills in regulating behavioral and attentional control are associated to academic and social competences (Eisenberg et al., 1997b).

Little is known about the importance of family processes and child’s/adolescents’ factors and the ways in which these factors determine academic and social competences of school-aged children (King et al., 2005). Therefore, it is important to investigate the relative contributions of family functioning and child/adolescence’s psychological adjustment and well-being.

In line with the aforementioned, the present study has two main purposes. The first goal is to translate and evaluate the psychometric properties of a European Portuguese version of the Family Sense of Coherence Scale (FSOC), in order to enable its usefulness in clinical and cross-cultural studies. Secondly, another purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of the familiar functioning in the psychological adjustment in a Portuguese sample with caregivers of children between 10 and 15 years old.

Method

Participants

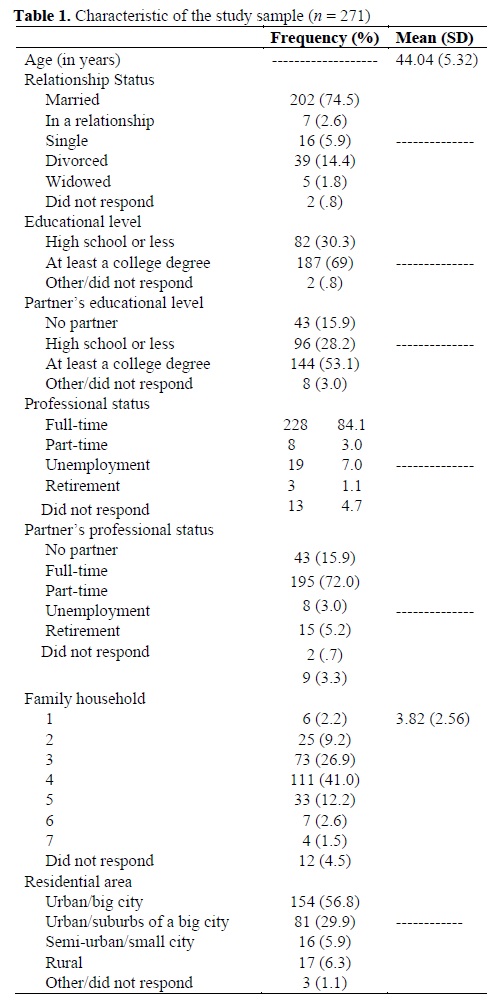

This study is part of a larger national study with children, their caregivers and their teachers. This sample comprised a total of 271 caregivers (189 mothers, 73 fathers, two stepfathers, two stepmothers, two grandmothers, one grandparent and one civil godmother) from a community sample. As can be seen in Table 1 , caregivers’ ages ranged between 25 to 70 years old (M = 44.04; DP = 5.32). Children’s mean age was 12 years old (DP = 1.72). Most of the caregivers were married (75.1%), held a college degree (69 %), were full-time employed (84.1%) and lived in an urban area/big city (56.8%).

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Having Portuguese nationality; and (2) having a child between the ages of 10 and 15 years old.

Measures

Before completing the study measures, participants answered a brief sociodemographic questionnaire including age, relationship to the child, marital status, educational level, professional status, partner’s educational level, partner’s professional status and residential area, and family characteristics, namely child’s age, child relationship with the partner and family household.

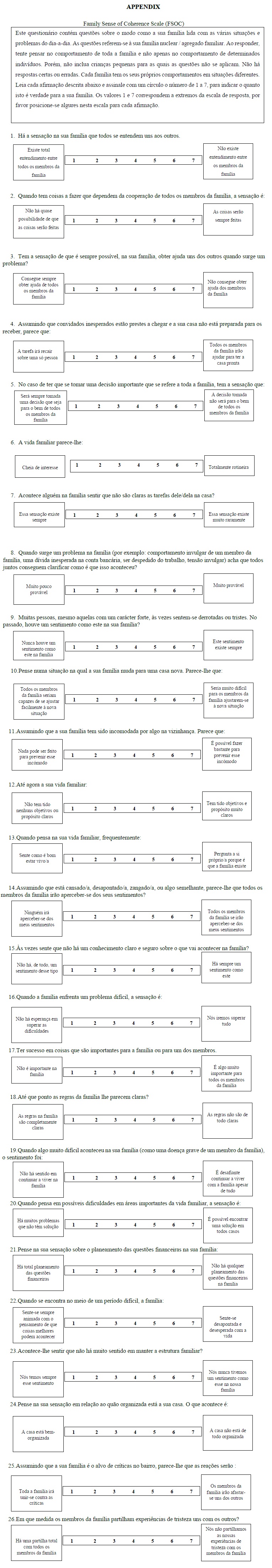

Family Sense of Coherence. Family Sense of Coherence Scale FSOC was created by Antonovsky and Sourani (1988) and evaluates a global cognitive orientation of the family to see the world as one's world as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful. FSOC was based on the Sense of Coherence Scale (Antonovsky, 1987) and adapted to family life. The scale is composed by three subscales, namely, Comprehensibility, Manageability and Meaningfulness. The first subscale refers to the family’s cognitive orientation to family life according to the degree of predictability and explicability of family life (e.g. ‘‘Do you sometimes feel that there’s no clear and sure knowledge of what’s going to happen in the family?’’). The second subscale refers to the extent to which family resources are available to face the demands caused by family stressors unit (e.g., ‘‘When you think of possible difficulties in important areas of family life, is the feeling, there are problems which have no solution?’’. The third subscale refers to the degree to which family understands the demands as worthy of investment by (e.g., ‘‘Family life seems to you full of interest’’). FSOC consists of 26 items scored from 1 to 7 with extreme anchor phrases. High scores correspond to a strong FSOC. Cronbach’s alphas for the total Scale was .92. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales Comprehensibility, Manageability, and Meaningfulness subscales were .77, .80, and .85, respectively.

The initial phase of this study implied the translating and back-translating of the FSOC items and instructions. A group of five psychology researchers, fluent in both Portuguese and English, was combined to help in the translation process. After some discussion meetings, a consensus version was developed (FSOC Portuguese version in Appendix section).

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. The caregivers of this study also completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). SDQ was originally created by Goodman (1997). The Portuguese version was translated by Fleitlich, Loureiro, Fonseca, and Gaspar (2005). SDQ (Goodman, 1997) evaluates the existence of emotional and behavioral difficulties. SDQ was originally constituted by five subscales, however, recent studies have suggested that a three-dimensional scale is more suitable for low-risk community samples (Costa, Tasker, Ramos, & Leal, 2019; Goodman, Lamping, & Ploubidis, 2010). These three subscales are the following: Internalizing Problems (I), Externalizing Problems (E) and Prosocial Behaviors (P). SDQ consists in 25 items scored from 0 to 2 points. The Portuguese version of parent’s samples presented acceptable values of internal consistent for the three subscales (Internalizing Problems (α = .74), Externalizing Problems (α = .78) and Prosocial Behaviors (α = .69) (Goodman et al., 2010).

Procedures

The sampling method was twofold. The first part (n = 195) was a non-probabilistic convenience sample recruitment in private schools and learning centers from the Lisbon metropolitan area and from Setubal district/area. Some of these participants completed via Paper and Pencil (P&P) and others completed via online questionnaires. The second part of the sample replied only via online questionnaires (n = 76) and the dissemination of the study recruitment was made through social networks. The sample recruitment occurred between November 2018 and September 2019. According to Declaration of Helsinki, all participants were given the option to clarify any question related to study characteristics through email or personally, depending if it was the presential recruitment or the online recruitment. To all participants it was provided informed consent and were assured confidentiality before accepting to participate in the study.

Data Analysis

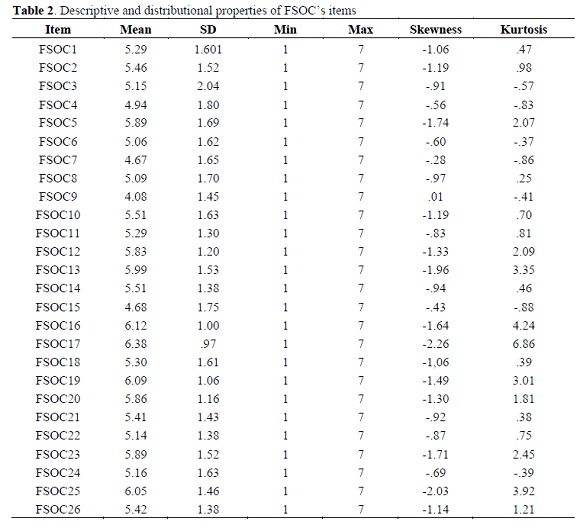

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, minimum, maximum, skewness and kurtosis) were computed for the items of the FSOC’s Portuguese version. Items’ sensitivity were evaluated through Skewness (Sk) and Kurtosis (K) analysis. Absolut values of |Sk| and |K| higher than three and seven, respectively, were considered as a severe violation of normality assumption (Marôco, 2014)

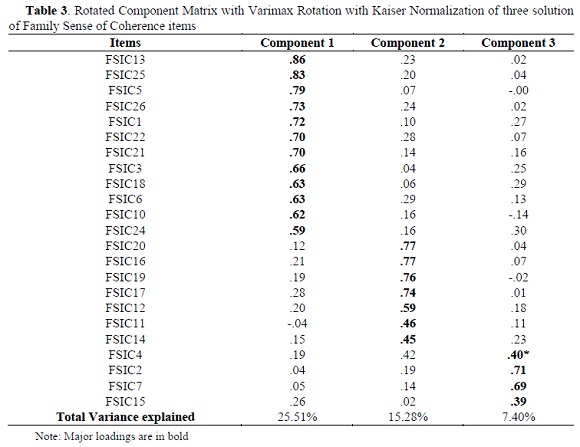

For the first main goal, FSOC Portuguese version validity was tested. For the assessment of construct validity, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were conducted. An EFA was conducted to explore the original three-factor structure of the FSOC. To verify if the data were suitable for EFA, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were tested. KMO must be equal or above .6 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity value must be significant (.05 or smaller). EFA was performed using the principal components method and a varimax rotation.

To confirm the factor solution found in the EFA, a CFA was performed. Statistical analyses were performed using AMOS (v. 18, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Model adjustment was verified through the following indexes: The goodness-of-fit indices TLI (Tucker Lewis Index), NFI (Normed Fit Index), χ2/df (ratio chi-square and degrees of freedom), CFI (comparative fit index), RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) and Standardized RMR were used. The model was considered as having a good fit if χ2/df was smaller than 5, if CFI, NFI and TLI values were higher than .95 and if RMSEA and Standardized RMR values were lower than .08 (Byrne, 2016; Marôco, 2014)

Model’s adjustment was performed step-by-step, according to Byrne’s (2016) guidelines. Based on parameter estimates’ statistical significance only items with a probability level of .05 were considered. For the loading factors we decided to maintain items that with standardized regression weights above .40 and squared multiple correlations above .15).

To analyze FSOC convergent-related validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) was estimated. Values of AVE above .50 were considered indicative of the constructs’ convergent-related validity (Marôco, 2014). Discriminant-related validity was explored through the comparison of the inter-factors’ squared correlation with the AVE of each individual factor. Evidence of discriminant-related validity is found when the squared correlation between factors is smaller than the individual AVE (Marôco, 2014). The reliability of the FSOC, was investigated through internal consistency estimates, namely, the Composite Reliability (CR) of the factors and the standard Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) for FSOC total scale and subscales (Marôco, 2014).

For the second goal, firstly we transformed the original scores into standardized scores. Standardized scores include the factorial weights ponderation given by CFA. Using these standardized scores, a Multiple Linear Regression Analysis was performed to obtain a parsimonious model that could predict the psychological adjustment (SDQ dimensions) according to the family functioning (FSOC dimensions). This analysis was performed with SPSS statistic program (v.22; IBM SPSS Chicago, IL). For all analysis in this study it was considered a type 1 error probability (α) of .05.

Results

The results presentation followed the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing framework.

Descriptive Data

As can be seen in Table 2, there were no items with skewness and kurtosis values that were indicative of severe normality deviations (.01< [Sk] < -2.25; .25< [K] < 6.67) (Kline, 2016). All possible answer values for each item were present (1-7), meaning that the entire 7-point liker scale was used for all items.

Construct-Related Validity: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

EFA was performed in order to examine the FOSC original structure. The 26 items of the FSOC scale were subjected to principal components analysis (PCA). Prior to this analysis, the suitability of data for EFA was assessed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was excellent (.92), exceeding the recommended value of .6. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity presented statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix (Pallant, 2016). PCA revealed the presence of five possible dimensions with eigenvalues greater than one although the assessment of the factor loadings and item distribution indicated there were three dimensions. To confirm the three-factor solution of the FSOC scale, varimax rotation was performed (Table 3). The rotated solution revealed a substantial number of strong loadings distributed mainly between the first and the second component. Items 8, 9 and 23 were excluded based on their factor loadings (under .4). Item 4 presented a loading difference of less than .05 between component 2 and 3, although we decided to include this item in dimension 3 because it has greater theoretical frame. The third component had two items with high loadings. Item 15’s loading was close to .40, and therefore we decided to maintain it this item because theoretically it is relevant for the third dimension.

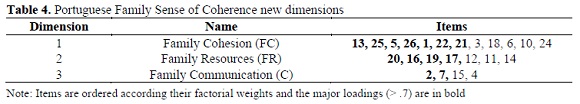

According to EFA, the FSOC for this sample should maintain a three-factorial structure, as the original scale, however with dimensions composed with a new item aggregation (see Table 4). The first dimension included the items 13, 25, 5, 26, 1, 22, 21, 3, 18,6,10, 24 and was named Family Cohesion (FC). The second dimension was named Family Resources (FR) and included the items 20, 16, 19, 17, 12, 11 and 14. The last dimension, was named as Family Communication (C) and included the items 2, 7, 15 and 4.

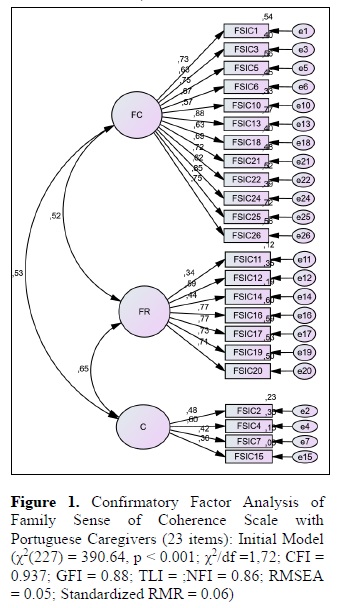

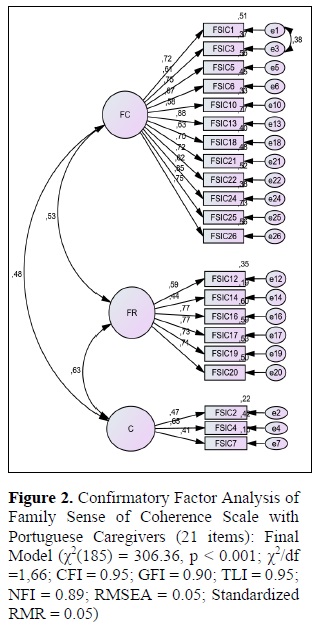

Construct-Related Validity: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The three-factor model of FSOC based on the EAF solution demonstrated acceptable fit to the data (χ2(227) = 390.64, p < .001; χ2/df =1,72; CFI = .94; GFI = .89; TLI = ;NFI = .86; RMSEA = .05; Standardized RMR = .06), with all factor loadings above .4, except for items 11 and 15. The three factors were all significantly correlated. After eliminating items 11 and 15, and adding one error term correlation, the combined fit indices for the CFA supported the new three-factor solution (χ2(185) = 306.360, p < .001; χ2/df =1,66; CFI = .95; GFI = .90; TLI = .95; NFI = .89; RMSEA = .05; Standardized RMR = .0).

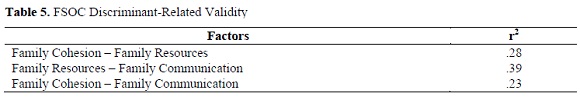

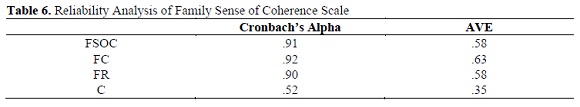

Convergent-Related, Discriminant-Related Validity and Reliability

FSOC’s convergent-related validity was examined through the average variance extracted (AVE). Family Cohesion and Family Resources presented high AVE scores (.63 and .58, respectively). However, the third dimension Family Communication revealed a low value of AVE (.35). FSOC total scale presented a good AVE score (.58) which indicates that FSOC for this sample has a good convergent-related validity. Discriminant-related validity was good for the existent factors, except for C dimension. For Communication dimension, inter-factors squared correlation between Family Cohesion and Family Communication was slightly higher than AVE’s Family Communication (Table 5).

Composite Reliability of Family Cohesion, Family Resources and FSOC total scale was very good. Family Communication dimension presented a low value of Composite Reliability. Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) of Family Cohesion was excellent (α =.92) and for Family Resources was good (α= .90). However, for the Family Communication, Cronbach’s value was not acceptable (α = .52). Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) for FSOC total scale was excellent (α = .91) (Table 6). Systematic removal of each item had no impact on the alphas. This scale presents a very good level of internal consistency in our sample, except the third FSOC dimension.

The Impact of the Familiar Functioning on Children’s Psychological Adjustment

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) was used to evaluate the impact of the familiar functioning in the psychological adjustment. Three MLR were performed with each SDQ dimensions and FSOC subscales. This analysis was performed with standardized scores of FSOC scale. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity.

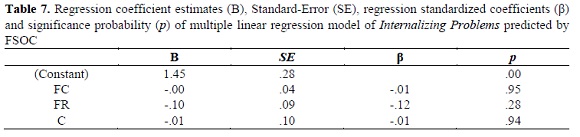

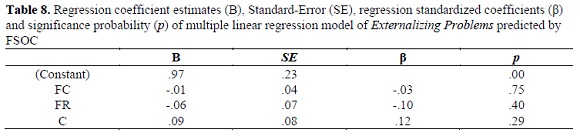

FSOC dimensions were not significant predictors of SDQ Internalizing Problems, F (3,20) = 1.19; R2adj = .003; p = .32 (Table 7). Similarly, FSOC dimensions were not significant predictors of SDQ Externalizing Problems, F (3,202) = .41; R2a = -.009; p = .75 (Table 8).

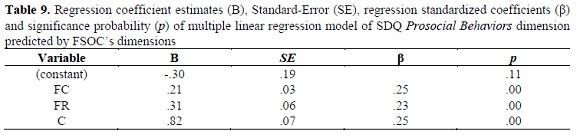

Conversely, Family Cohesion, Family Resources and Family Communication were significant predictors of SDQ Prosocial Behaviors dimension (Table 9). Family Communication was the highest predictor of the Prosocial Behaviors dimension, recording a higher beta value. This model was significant, F (3,27) = 361.552; p < .001 and explained an elevated percentage of the P dimension variability (R2adj = .80).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Family Sense of Coherence (FSOC) using a sample of Portuguese caregivers with children aged between 10 to 15 years old. Findings suggest that the new FSOC factorial model revealed a goodness of fit significantly higher than the original structure model proposed by the authors. The new model maintains a three-factor structure, however without the original item’s organization. FSOC proposed in the present study is composed by 21 items. The overwhelming majority of the items was redistributed from the FSOC original dimensions (Meaningfulness, Manageability and Comprehensibility) into Family Cohesion and Family Resources dimensions. The items comprising Family Communication dimension, have derived from the original dimensions Manageability and Comprehensibility.

The new FSOC dimensions proposed in the present study were named as Family Cohesion, Family Resources and Family Communication. Family cohesion refers to ‘the emotional bonding that family members have toward one another’ (Olson, 2011, p. 65). This dimension includes items such as “When you think about your family life, you very often (feel how good it is to be alive . .. ask yourself why the family exists)” (item 13), “Let's assume that your family is the target of criticism in the neighborhood. Does it seem to you that your reactions will be (the whole family will join together against the criticism. . . family members will move apart from each other)” (Item 25), and “To what extent do family members share sad experiences with each other? (there's complete sharing with all family members... we don't share our sad experiences with family members)” (Item 26).

Family Resources. According to Antonovsky and Sourami (1988), there is a tendency to expect a certain level of manageability of the challenges proposed by stressores. Consequently, this leads to a evaluation and pursuit of the appropriate resources. An elevated FSOC corresponds to good motivational and cognitive bases, which allows individuals and families to transform their potential resources into an adequate stressor response and therefore promoting health. Resources could be psychological (e.g. emotional), psychical, social, financial, and/or specific skills (Beutell & Gopalan, 2019), among others. Family Resources dimension includes items such as “When you think of possible difficulties in important areas of family life, is the feeling (there are many problems which have no solution ... it's possible in every case to find a solution” (Item 20), “When the family faces a tough problem, the feeling is (there's no hope of overcoming the difficulties . . . we'll overcome it all)” (Item 16), and “When something very difficult happened in your family (like a critical illness of a family member), the feeling was (there's no point in going on living in the family. .. this is a challenge to go on living in the family despite everything)” (Item 19).

Family communication is defined as a family communication competency and is a facilitating variable, since it promotes family cohesion (Olson, 2011). This dimension includes the following items: “When you have to get things done which depend on cooperation among all members of the family, your feeling is: (there's almost no chance that the things will get done . . . the things will always get done) (Item 2), “Does it happen that someone in the family feels as if it isn't clear to him/her what his/her jobs are in the house? (this feeling exists all the time . . . this feeling exists very rarely)” (Item 7) and “Do you sometimes feel that there's no clear and sure knowledge of what's going to happen in the family? (there's no such feeling at all ... there's always a feeling like this)” (Item 15).

The findings suggest a very good FSOC reliability and validity. The scale’s internal consistency is excellent, with a good reliability score of .91 and a composite reliability coefficient score of .58. FSOC’s dimension Family Communication was an exception for a good internal consistency. However, this dimension is composed only by three items, which could explain these values. These items are relevant for FSOC scale because, according to many studies, communication is an important and significant variable for family functioning (King, et al., 2005; Smith, et al., 2016). In addition, we have decided to preserve this third dimension in order to maintain a three-factor solution, as the original FSOC structure.

FSOC was developed in 1988 and to the best of our knowledge no studies have been conducted to explore and confirm FSOC original factorial structure. Few international studies have made a translation and validation of FSOC short version.

FSOC was originated from Sense of Coherence (SOC) and this construct has been used all over the world. It has been used in at least 49 different languages and at least in 48 countries (Eriksson & Mittelmark, 2017). Conversely, FSOC has not been significantly explored in the literature. Since this is related to a salutogenic approach of family functioning and processes, it could be important to investigate more about this theory and scale, for clinical and research purposes. In fact, the exponential interesting in family systems and processes referred by researchers and family practitioners (Gomes, Peixoto, & Gouveia-Pereira, 2017) combined with the lack of suitable Portuguese instruments to evaluate family functioning, makes FSOC relevant for the research and clinical field.

The second purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of familiar functioning on children’s psychological adjustment. Findings revealed that FSOC has significant impact on Prosocial Behaviors. Family Communication presented the highest correlation with Prosocial Behaviors. According to several studies, family communication is highly associated with children and adolescence’s positive health outcomes, such as prosocial values and behaviors (see for example, Hillaker, Brophy-Herb, Villarruel, & Haas 2008). Supportive parent-child relationships predict the acquisition of social competences (Barry, Padilla-Walker, Madsen, & Nelson, 2007).

Findings do not support evidence for a significant relationship between FSOC and Internalizing Problems or Externalizing Problems. FSOC, as being part of salutogenic theoretical framework, is very oriented to an optimistic perspective, which could explain these findings association with the mentioned scales. Also, the study sample is a non-clinical one, which could be another justification for a non-association between FSOC and the mentioned scales.

Child adjustment is a complex process that is influenced by several interactions between factors, such as personal, family, and environmental (King, et al., 2005). In the present study, family sense of coherence is a strong predictor of prosocial behaviors. Although family structure has impact on children’s developmental outcomes, family processes and functioning have significantly more influence than family structure per se (see for example, Amato, 1987; Ginther & Pollak, 2004; Manning & Lamb, 2003). The experiences of children’s daily life within familial circumstances are very important for child’s psychosocial adjustment (Wu et al., 2008). According to King and colleagues, the most relevant predictors of children’s wellbeing appears to be family cohesion and parents’ social support. In this respect, literature suggests that family functioning is directly associated to adolescent behaviors and development (Smith et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2016). King and colleagues’ study demonstrated that an increased family functioning is associated to a higher peer affinity. The authors have also revealed that a good family functioning leads to lower levels of aggressive behavior and to higher levels of prosocial behavior. This highlights the importance of the family in promoting children’s self-regulatory skills that will help auto-monitoring their behavior and experience. In turn, these skills, are related to academic and social competence (Eisenberg et al., 1997b). Several researchers have reported associations between family functioning and children’s behavioral functioning (see for example, Kronenberger & Thompson, 1990) and between behavioral functioning and prosocial behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1997a).

There are a number of study limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. This study is a cross-sectional design and therefore it was not possible to evaluate test-retest stability and predictive validity of the FSOC. Future studies are needed to examine the stability of FSOC over time, as well to determine the potential beneficial effects of therapeutic interventions that promote families’ FSOC. In this study, other family functioning measures were not applied which would help establish FSOC convergent validity. Additional studies are needed to add this information about FSOC. Finally, another study limitation is related to the convenience sampling method. It was not possible to determine how representative the sample is of the Portuguese families with children between 10 to 15 years old. Further research is needed to help establish the findings generalization.

Nevertheless, our findings provide support for a new FSOC structure with good reliability and psychometry properties for a sample of families with children aged between 10 to 15 years old. This measure may be useful for understand the importance of family functioning for children’s and adolescence psychosocial adjustment, as well as for cross-cultural research that pretends to evaluate similarities and differences about the family role in psychological adjustment, especially on prosocial behaviors. The present study has refocused on a concept that has been insufficiently researched and that could be very relevant for family researchers and family therapists, since it helps determine and enhancing family sense of coherence (and indirectly their resilience), which would help them to achieve a better health and well-being.

REFERENCES

Amato, P. R. (1987). Family processes in one-parent, stepparent, and intact families: The child’s point of view. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49(2), 327-337. [ Links ]

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress, and coping. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). The salutogenic perspective: Toward a new view of health and ilness. Advances, 4, 47-55. [ Links ]

Antonovsky, A., & Sourami, T. (1988). Family sense of coherence and family adaptation. Journal of Mariage and the Family, 50 (1), 79-92. DOI: 10.2307/352429. [ Links ]

Barry, C. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Madsen, S. D., & Nelson, L. J. (2007). The impact of maternal relationship quality on emerging adults’ prosocial tendencies: Indirect effects via regulation of prosocial values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(5), 581-591. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-007-9238-7. [ Links ]

Beutell, N.J. & Gopalan, N. (2019): Pathways to work-family synergy: resources, affect and wellbeing, Journal of Family Studies, 1-17. DOI: 10.1080/13229400.2019.1656664.

Byrne, B. (2016). Structural equation modeling with Amos: basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Çeçen, A. R. (2007). The Turkish Version of the Family Sense of Coherence Scale-Short Form (FSOC-S): Initial Development and Validation. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 7(3), 1211-1218. [ Links ]

Costa, P. A., Tasker, F., Ramos, C., & Leal, I. (2019). Psychometric properties of the parent's version of the SDQ and the PANAS-X in a community sample of Portuguese parents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. [Advanced online] [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Murphy, B. C., Guthrie, I. K., Jones, S., … Maszk, P. (1997). Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of children’s social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development, 4, 642-664. [ Links ]

Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I. K., Fabes, R. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Holgren, R., … Losoya, S. (1997). The relations of regulation and emotionality to resiliency and competent social functioning in elementary school children. Child Development, 68, 295-311. [ Links ]

Eriksson, M., & Mittelmark, M. (2017). The Sense of Coherence and Its Measurement. In S. S. Mittelmark M.B. (Ed.), The Handbook of Salutogenesis (pp. 97-106). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland. [ Links ]

Fleitlich, B., Loureiro, M., Fonseca, A., & Gaspar, F. (2005). Questionário de Capacidades e Dificuldades (SDQ-Por). Retrieved from www.sdqinfo.com [ Links ]

Gomes, H., Peixoto, F., & Gouveia-Pereira, M. (2019). Portuguese validation of the family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scale - FACES IV. Journal of Family Studies, 25(4), 477-494. DOI: 10.1080/13229400.2017.1386121. [ Links ]

Ginther, D. K., & Pollack, R. A. (2004). Family structure and children’s educational outcomes: Blended families, stylized facts, and descriptive regression. Demography, 41(4), 671-696. [ Links ]

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581-586. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [ Links ]

Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179-1191. DOI: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x. [ Links ]

Hillaker, B. D., Brophy-Herb, H. E., Villarruel, F. A., & Haas, B. E. (2008). The contributions of parenting to social competencies and positive values in middle school youth: Positive family communication, maintaining standards, and supportive family relationships. Family Relations, 57(5), 591-601. [ Links ]

King, G., McDougall, J., DeWit, D., Hong, S., Miller, L., Offord, D., … LaPorta, J. (2005). Pathways to children’s academic performance and prosocial behavior: Roles of physical health status, environmental, family, and child factors. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 52(4), 313-344. DOI: 10.1080/10349120500348680. [ Links ]

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, (4th Ed). New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

Kronenberger, W. G., & Thompson, R. J., Jr. (1990). Dimensions of family functioning in families with chronically ill children: A higher order factor analysis of the Family Environment Scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19(4), 380-388. DOI: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1904_10. [ Links ]

Lindström, B., & Eriksson, M. (2006). Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development. Health Promotion International , 21(3), 238-243. DOI: 10.1093/heapro/dal016. [ Links ]

Manning, W. D., & Lamb, K. A. (2003). Adolescent well-being in cohabiting, married, and single-parent families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 876-893. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00876.x. [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações. Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal: ReportNumber.

Moen, Ø.L., & Hall-Lord, M.L. (2016). Reliability and Validity of the Norwegian Family Sense of Coherence Scale. Open Journal of Nursing, 6, 1075-1086. DOI: 10.4236/ojn.2016.612102. [ Links ]

Möllerberg, M. L., Årestedt, K., Sandgren, A., Benzein, E., & Swahnberg, K. (2019). Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the short version of Family Sense of Coherence Scale in a sample of persons with cancer in the palliative stage and their family members. Palliative & supportive care, 9, 1-9. DOI: 10.1017/S1478951519000592. [ Links ]

Ngai, F. W., & Ngu, S. F. (2011). Translation and validation of a Chinese version of the family sense of coherence scale in Chinese childbearing families. Nursing research, 60(5), 295-301. DOI: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182269b00. [ Links ]

Olson, D. (2011). FACES IV and the circumplex model: Validation study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(1), 64-80. DOI: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x. [ Links ]

Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual - A Step By Step Guide To Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS (6th ed.). Berkshire, England: Mc Graw Hill Education.

Smith, E. P., Faulk, M., & Sizer, M. A. (2016). Exploring the meso-system: The roles of community, family, and peers in adolescent delinquency and positive youth development. Youth & society, 48(3), 318-343. DOI: 10.1177/0044118X13491581. [ Links ]

Smith, E. P., Prinz, R. J., Dumas, J. E., & Laughlin, J. (2001). Latent models of family processes in African American families: Relationships to child competence, achievement, and problem behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 967-980. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00967.x. [ Links ]

Söderhamn, O., & Holmgren, L. (2004). Testing Antonovsky’s sense of coherence (SOC) scale among Swedish physically active older people. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , 45(3), 215-221. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00397.x. [ Links ]

Tasker, F. (2005). Lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children: a review. Developmental and behavioral pediatrics, 26(3), 224-240. [ Links ]

Wickens, L., & Greeff, A. P. (2005). Sense of family coherence and the utilization of resources by first-year students. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 33(5), 427-441. DOI: 10.1080/01926180490455303. [ Links ]

Wu, Z., Hou, F., & Schimmele, C. M. (2008). Family structure and children's psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Family Issues, 29(12), 1600-1624. DOI: 10.1177/0192513X08322818. [ Links ]

Recebido em 01 de Março de 2019/ Aceite em 01 de Novembro de 2019

APPENDIX