Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças

versão impressa ISSN 1645-0086

Psic., Saúde & Doenças vol.21 no.2 Lisboa ago. 2020

https://doi.org/10.15309/20psd210211

Medical students’ trust in their family physician

Confiança dos estudantes de medicina nos seus médicos de família

Filipe Prazeres1,2,3, Lígia Passos4, Patricia Almeida5, Manuel Loureiro6,7, Luiz Santiago5,8, & José Simões1,3,9

1Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, filipeprazeresmd@gmail.com

2USF Beira Ria, Gafanha da Nazaré, Portugal

3Centre for Health Technology and Services Research (CINTESIS), Porto, Portugal

4Departamento de Educação e Psicologia, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, ligiamaria@ua.pt

5Clínica Universitária de Medicina Geral e Familiar da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. patricia.paiva.almeida@gmail.com

6Departamento de Psicologia e Educação da Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, loureiro@ubi.pt

7Centro de Investigação em Desporto, Saúde e Desenvolvimento Humano, Portugal

8CEISUC - Centro de Estudos de Investigação em Saúde da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. lmsantiago@netcabo.pt

9USF Caminhos do Cértoma, Pampilhosa, Portugal jars58@gmail.com

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Trust is an essential part of a good physician-patient relationship and measuring it allows to improve the healthcare system. Medical students can evaluate physicians’ technical competency more profoundly than a layperson, so it is possible to evaluate a less asymmetrical interpersonal trusting relationship than the one between physician and patient. This study aimed to: (i) measure the level of medical students’ trust in their family physicians; (ii) study the differences between medical students’ characteristics and the level of trust; and (iii) measure the attitudes towards doctors of medical students and their relationship to trust in family physicians. A cross-sectional study was carried out with a convenience sample of medical students from two Portuguese public universities. Students were invited to answer a web-based questionnaire that included sociodemographic and academic variables, the Trust in Physician Scale (TIPS) and the attitudes towards doctors’ factor of the Attitudes to Doctors and Medicine Scale. Data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. 172 medical students responded to the questionnaire. Most were female (74.4%) and the mean age was 23.7 (SD 2.3 years). 80.8% were students from the clinical cycle. A moderate trust in family physicians was found (mean total score of TIPS was 3.7 (SD 0.7), and a positive attitude toward doctors was more frequent than the negative one. Older age, good teaching quality in family medicine, and seeking family physicians for urgent care appear to be associated with students’ higher trust in family physicians, but this needs to be studied further using larger samples.

Keywords: trust, medical students, family physician, physician-patient relationship

RESUMO

A confiança é parte essencial do bom relacionamento médico-doente, e medi-la permite melhorar o sistema de saúde. Estudantes de medicina podem avaliar a competência técnica dos médicos mais profundamente do que leigos, assim é possível avaliar uma relação de confiança interpessoal menos assimétrica do que aquela entre médico e doente. Este estudo teve como objetivo: (i) medir o nível de confiança dos estudantes de medicina nos seus médicos de família; (ii) estudar as diferenças entre características dos estudantes de medicina e o nível de confiança; e (iii) medir as atitudes em relação aos médicos dos estudantes de medicina e sua relação com a confiança nos médicos de família. Foi realizado um estudo transversal com amostra de conveniência de estudantes de medicina de duas universidades públicas portuguesas. Os alunos responderam a um questionário sociodemográfico, a Trust in Physician Scale (TIPS) e ao fator atitudes em relação aos médicos da Attitudes to Doctors and Medicine Scale. 172 estudantes de medicina responderam ao questionário. A maioria era do sexo feminino (74,4%) e a média de idades foi de 23,7 anos (DP = 2,3 anos). 80,8% eram estudantes do ciclo clínico. Foi encontrada uma confiança moderada nos médicos de família (pontuação total média da TIPS = 3,7 (DP = 0,7)) e uma atitude positiva em relação aos médicos foi mais frequente do que a negativa. Idade avançada, boa qualidade do ensino em Medicina Familiar e procura dos médicos de família para atendimento de urgência parecem estar associados à maior confiança dos alunos nos médicos de família.

Palavras-chave: confiança, estudantes de medicina, médico de família, relação médico-doente.

The physician-patient relationship is an important element in medicine and when it is a positive interaction it improves treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction (Vidal et al., 2019). It has previously been defined as “a consensual relationship in which the patient knowingly seeks the physician’s assistance and in which the physician knowingly accepts the person as a patient” (QT Inc. v. Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

It is associated with the physician's ability to fulfil the needs of each patient (Vidal et al., 2019) and it reflects professionalism and is the center of quality health care (Sari, Prabandari, & Claramita, 2016).

Two models can summarize the relationship between the physician and his/her patient (McWhinney, 1985): the physician-centered model that inhibits the patient from having an active role in the consultation and by not controlling the exchange of information; and the patient-centered model, in which patients participate actively in their treatment making them more responsible for their health (McWhinney, 1985). For this cooperation and patient participation to happen, the building of trust is one of the main elements (Ahmad et al., 2015; Bültzingslöwen, Eliasson, Sarvimäki, Mattsson, & Hjortdahl, 2005; Illingworth, 2002).

Trust, in this context, is a concept associated to feelings of being believed and taken seriously (Bültzingslöwen et al., 2005), it is the acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the patient has to believe that the physician will act in the patient's best interests (Thom, Hall, & Pawlson, 2004). A patient develops trusts in the physician when he/she recognizes in the latter technical/interpersonal competency and loyalty (Kalsingh, Veliah, & Gopichandran, 2017; Thom et al., 2004). Unlike satisfaction, which concerns patients' experiences regarding attitudes taken by their physician in the past, trust is about the present relationship and patient's emotional expectations of physician’s future behavior (Thom et al., 2004, 2011).

Trust, as a part of a good physician-patient relationship, improves compliance to treatment plans, continuity of care, efficient divulgence of sensitive medical information, better self-reported health status, and fewer unnecessary referrals or tests (Kalsingh et al., 2017; Thom et al., 2004).

Several papers have studied trust in health care (Lisowska, Szwamel, & Kurpas, 2019; Müller, Zill, Dirmaier, Härter, & Scholl, 2014; Szwamel & Kurpas, 2016), but few studies were done regarding family medicine, a setting where the physician-patient relationship is longitudinal and of continuity (Marcinowicz et al., 2017).

Measuring trust of patients that are also medical students has several advantages. It will allow to study a different view of the healthcare system (rather than the most commonly assessed - the experience of the patient); and since medical students will be able to judge family physicians’ technical competency more profoundly than a non-medical student, it will be possible to see whether family physicians deserve the level of trust they are receiving. It will also be possible to evaluate a less asymmetrical interpersonal trusting relationship than the one between physician and patient, since the family physician and the medical student have almost equal decisional power in this relationship. In the future, measuring trust will allow medical schools to change medical students training to promote patient trust.

This paper aimed to: (i) measure the level of medical students’ trust in their family physicians; (ii) study the differences between medical students’ characteristics and the level of trust; and (iii) measure the attitudes towards doctors of medical students and their relationship to trust in family physicians.

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional study was carried out between June and November 2019, with a convenience sample of medical students from two Portuguese public universities - University of Beira Interior and University of Coimbra (margin of error of +/- 10 percentage points at the 95% confidence level). Students were invited to answer a web-based questionnaire that included sociodemographic and academic variables, the Trust in Physician Scale (TIPS) (Anderson & Dedrick, 1990) and the attitudes towards doctors factor of the Attitudes to Doctors and Medicine Scale (Marteau, 1990). This invitation was followed by a monthly email reminder to students who had not yet responded.

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board of both institutions. All participants signed an informed consent form. Responses were anonymous.

Material

The Trust in Physician Scale (TIPS) was developed by Anderson and Dedrick (Anderson & Dedrick, 1990) to measure patients’ trust in their physician. To the authors trust is “a person’s belief that the physician’s words and actions are credible and can be relied upon” (Anderson & Dedrick, 1990, p. 1092). Using a five point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree), the 11-item self-reported scale evaluates: (i) interpersonal trust in physician, (ii) trust in physician's knowledge and skills, and (iii) confidentiality and reliability of information received from the physician. The scale was translated and validated for the Portuguese population (Pereira, Pedras, & Machado, 2013). Both the original and the Portuguese version show adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha 0.91 and 0.82, respectively). This is also true for studies within primary care (Thom, Ribisl, Stewart, & Luke, 1999). Higher scores reflect greater trust. When completing the scale, medical students were instructed to think of the family physician who usually provided their care.

The Attitudes to Doctors and Medicine Scale (ADMS) (Marteau, 1990) was developed to measure people's attitudes towards medicine and doctors. Its 17 items are divided into 4 factors: “positive attitude towards doctors,” “positive attitude towards medicine,” “negative attitude towards doctors,” and “negative attitude towards medicine.” The higher the score, the more attitudes can be positive or negative according to the factor evaluated. Pereira and Silva translated this scale into Portuguese language (Pereira & Silva, 1999). In the present study only the attitudes towards doctors (positive and negative factors) were measured.

Data analysis

Data analysis used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) for descriptive and inferential statistics. The internal consistency of the Trust in Physician Scale was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The differences in the levels of trust between qualitative variables were measured using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Correlation between the scores of Trust in Physician Scale and the Attitudes Towards Doctors Scale was assessed using the nonparametric Spearman’s correlation. The level of statistical significance considered was p<0.05.

Results

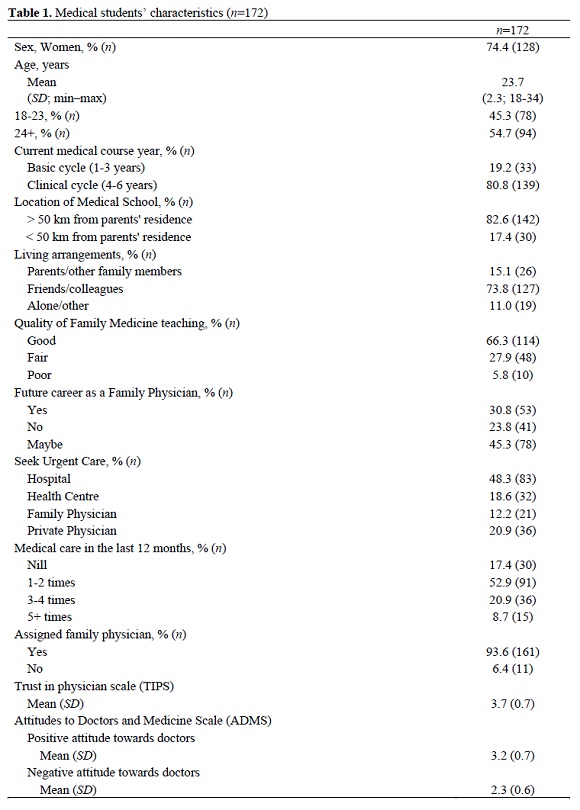

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample and mean scores of TIPS and Attitudes Toward Doctors. TIPS questionnaire had good internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha of 0.889. Among the 172 medical students that responded to the questionnaire, most were women (74.4%). The mean age was 23.7 (SD 2.3 years); 80.8% of the respondents were students from the clinical cycle and mostly were studying at more than 50 km from their parents' residence (82.6%). The quality of Family Medicine teaching was considered to be good by 66.3% of the respondents. Almost all students had a family physician (93.6%). Practically half of the students needed medical care one to two times in the last year; 48.3% seek urgent care at a hospital. In the future, when the time comes to choose a medical specialty, 76.1% of the medical students will or may choose Family Medicine as their future career.

The mean total score of TIPS was 3.7 (SD 0.7), revealing a moderate trust in family physicians. Regarding the attitudes toward doctors in general, in the current sample the positive attitude was more frequent than the negative one (Table 1).

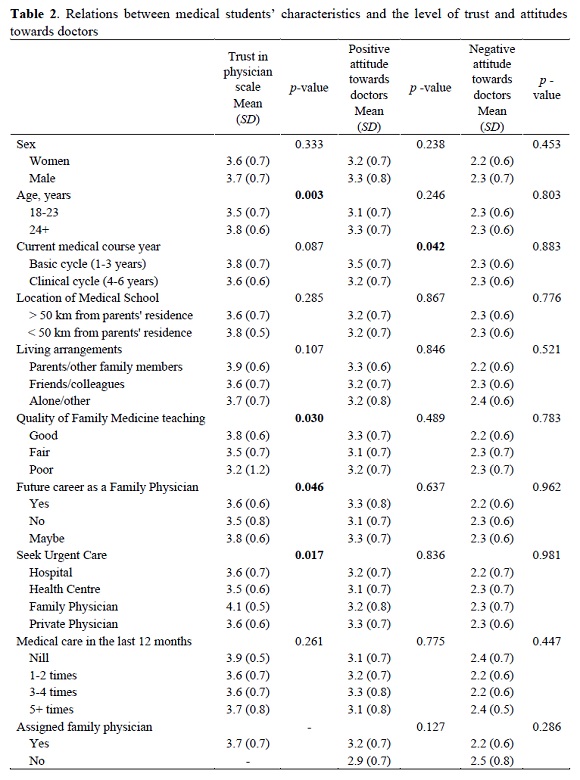

Higher levels of medical students’ trust in their family physicians were associated with older student age (p=0.003), good quality of family medicine teaching (p=0.030), possibility of choosing family medicine as a specialty (p =0.046) and seeking their family physicians for urgent care (p=0.017). Positive attitude towards doctors was positively associated with being in the basic cycle of medical school - 1 to 3 years (p =0.042) (Table 2).

There was a weak negative relationship (Dancey & Reidy, 2004) between trust and negative attitude towards doctors (rs=-0.20, p=0.011). Increases in trust were correlated with decreases in negative attitude towards doctors.

Discussion

Overall, the results of the current study indicate that medical students have a moderate trust in family physicians; and have more positive than negative attitudes toward doctors in general.

As mentioned in the literature review, medical students are more positive and less negative in their attitudes to doctors (Marteau, 1990). As expected, medical students’ unique experience of the healthcare system will favor low hostility towards family physicians, as intended by their medical training. Patients’ trust in physicians is generally high (Tarrant, Stokes, & Baker, 2003), especially in vulnerable populations (Tarrant et al., 2003) - where the relationship is unequal; but since the interpersonal relationship between the medical student and the family physician is a more symmetrical power relation it will be more difficult to develop into a high-trusting relationship (Cuevas, Julkunen, & Gabrielsson, 2015).

The present study raises the possibility that higher levels of students’ trust tended to endorse less negative attitudinal responses toward doctors, but not increases in positive attitude towards doctors. This finding, while preliminary, suggests that trust alone is not enough to establish a good physician-patient relationship. Even showing trust in specific circumstances, some patients may not practice positive attitudes and act with caution or pessimism, indicating a certain degree of distrust (Hall, Dugan, Zheng, & Mishra, 2001).

Prior studies have noted that the younger the patient, the greater is the trust in a physician (Freburger, Callahan, Currey, & Anderson, 2003; Marcinowicz et al., 2017). Nonetheless, even in a sample of young respondents, such as the current one (18 to 34 years), older students (24+ years) showed a higher level of trust in their family physicians. In accordance with the present results, previous studies showed that trust tends to increase as people age, as a resource for wellbeing during life span (Poulin & Haase, 2015); older people are more likely than younger ones to trust their physicians (Mascarenhas et al., 2006; Poulin & Haase, 2015) and to value more being involved in the decisions about their care (Croker et al., 2013).

In this study, students who recognize a good teaching quality in family medicine have a higher level of trust in their family physicians. Traditional medical education, based on the biomedical model, generally focuses on the continuous acquisition of clinical knowledge, offering less effort to teach good physician-patient relationships. Thus, some students may become physicians with few interpersonal skills and with difficulty in establishing a good relationship of trust with their patients (Ribeiro, Krupat, & Amaral, 2007; Vidal et al., 2019). When students develop good skills in the physician-patient relationship (Peixoto, Ribeiro, & Amaral, 2011), this can influence trust in their physicians, as well as their choice of future medical career (Matsui et al., 2007).

Another important finding was that higher levels of students’ trust were associated with the chance of seeking their family physicians for urgent care. A possible explanation for this might be that when patients’ trust is high, they realize that physician’s will place patient’s welfare above their own self-interest or of any other person, which is of particular importance in emergency scenarios where the patient may be unconscious or when a delay in treatment may cause serious harm. When there is a low trust in the ability of primary health care to deal with urgent situations, patients seek care in emergency units/hospitals, overloading them with health problems that could be resolved by family physicians (Damji et al., 2018).

This study had several limitations, not all national medical schools were explored, and a small sample of students was used (n=172). Future studies on the current topic are therefore recommended. Since cross-sectional studies cannot be used to determine causal relationships, a natural progression of this work is to analyse whether after entering the medical course the students' view of their family physician changes over time.

Despite the exploratory nature of the current study, the evaluation of the less asymmetrical interpersonal trusting relationship between the medical student and the family physician showed that medical students have a moderate trust in family physicians; and have more positive than negative attitudes toward doctors in general. Some aspects appear to be associated with students’ higher trust in family physicians: older age, good teaching quality in family medicine, and seeking family physicians for urgent care, but this needs to be studied further using larger samples.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, W., Krupat, E., Asma, Y., Noor-E-Fatima, Attique, R., Mahmood, U., & Waqas, A. (2015). Attitudes of medical students in Lahore, Pakistan towards the doctor-patient relationship. PeerJ, 2015(6), e1050. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.1050.

Anderson, L. A., & Dedrick, R. F. (1990). Development of the Trust in Physician scale: A measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychological Reports, 67(3 II), 1091-1100 DOI: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [ Links ]

Bültzingslöwen, I. von, Eliasson, G., Sarvimäki, A., Mattsson, B., & Hjortdahl, P. (2005). Patients’ views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations. Family Practice, 23(2), 210-219. DOI: 10.1093/fampra/cmi103. [ Links ]

Croker, J. E., Swancutt, D. R., Roberts, M. J., Abel, G. A., Roland, M., & Campbell, J. L. (2013). Factors affecting patients’ trust and confidence in GPs: Evidence from the English national GP patient survey. BMJ Open, 3(5), e002762. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002762. [ Links ]

Cuevas, J. M., Julkunen, S., & Gabrielsson, M. (2015). Power symmetry and the development of trust in interdependent relationships: The mediating role of goal congruence. Industrial Marketing Management, 48, 149-159. DOI: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.03.015. [ Links ]

Damji, A. N., Martin, D., Lermen, N., Pinto, L. F., Trindade, T. G. da, & Prado, J. C. (2018). Trust as the foundation: thoughts on the Starfield principles in Canada and Brazil. Canadian Family Physician, 64(11), 811-815. [ Links ]

Dancey, C., & Reidy, J. (2004). Statistics without maths for psychology: using SPSS for windows. London, England: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Freburger, J. K., Callahan, L. F., Currey, S. S., & Anderson, L. A. (2003). Use of the trust in physician scale in patients with rheumatic disease: Psychometric properties and correlates of trust in the rheumatologist. Arthritis Care & Research, 49(1), 51-58. DOI: 10.1002/art.10925. [ Links ]

Hall, M. A., Dugan, E., Zheng, B., & Mishra, A. K. (2001). Trust in Physicians and Medical Institutions: What Is It, Can It Be Measured, and Does It Matter? The Milbank Quarterly, 79(4), 613-639. DOI: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [ Links ]

Illingworth, P. (2002). Trust: The Scarcest of Medical Resources. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 27(1), 31-46. DOI: 10.1076/jmep.27.1.31.2969. [ Links ]

Kalsingh, M., Veliah, G., & Gopichandran, V. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Trust in Physician Scale in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 6(1), 34-38. DOI: 10.4103/2249-4863.214966. [ Links ]

Lisowska, A., Szwamel, K., & Kurpas, D. (2019). Factors determining patient admittance to the observation and consultation areas of the emergency department on workdays versus weekends. Family Medicine and Primary Care Review, 21(3), 230-236. DOI: 10.5114/fmpcr.2019.88381. [ Links ]

Marcinowicz, L., Jamiołkowski, J., Gugnowski, Z., Strandberg, E. L., Fagerström, C., & Pawlikowska, T. (2017). Evaluation of the trust in physician scale (TIPS) of primary health care patients in north-east poland: A preliminary study. Family Medicine and Primary Care Review, 19(1), 39-43. DOI: 10.5114/fmpcr.2017.65089. [ Links ]

Marteau, T. M. (1990). Attitudes To Doctors And Medicine: The Preliminary Development Of A New Scale. Psychology & Health, 4(4), 351-356. DOI: 10.1080/08870449008400403. [ Links ]

Mascarenhas, O. A. J., Cardozo, L. J., Afonso, N. M., Siddique, M., Steinberg, J., Lepczyk, M., & Aranha, A. N. F. (2006). Hypothesized predictors of patient-physician trust and distrust in the elderly: implications for health and disease management. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 1(2), 175-188. DOI: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.2.175. [ Links ]

Matsui, K., Ishihara, S., Suganuma, T., Sato, Y., Tang, A. C., Fukui, Y., … Yoshioka, T. (2007). Characteristics of Medical School Graduates who Underwent Problem-Based Learning. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 36(1), 67-71. [ Links ]

McWhinney, I. R. (1985). Patient-centred and Doctor-centred Models of Clinical Decision-making. In Sheldon M., Brooke J., Rector A. (Ed.), Decision-Making in General Practice (pp. 31-46). Palgrave, London: Macmillan Education UK. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-07159-3_4. [ Links ]

Müller, E., Zill, J. M., Dirmaier, J., Härter, M., & Scholl, I. (2014). Assessment of Trust in Physician: A Systematic Review of Measures. PLoS ONE, 9(9), e106844. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106844. [ Links ]

Peixoto, J. M., Ribeiro, M. M. F., & Amaral, C. F. S. (2011). Atitude do estudante de medicina a respeito da relação médico-paciente x modelo pedagógico. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 35(2), 229-236. DOI: 10.1590/s0100-55022011000200012. [ Links ]

Pereira, M. ., & Silva, N. . (1999). Escala de atitudes face aos médicos e à medicina. In A. Soares, S. Araújo, & S. Caires (Eds.), Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos (pp. 496-503). Braga: APPORT. [ Links ]

Pereira, M. D. G., Pedras, S., & Machado, J. C. (2013). Adaptação do questionário de confiança no médico em pacientes com diabetes tipo 2 e seus companheiros. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26(2), 287-295. DOI: 10.1590/S0102-79722013000200008. [ Links ]

Poulin, M. J., & Haase, C. M. (2015). Growing to Trust: Evidence That Trust Increases and Sustains Well-Being Across the Life Span. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(6), 614-621. DOI: 10.1177/1948550615574301. [ Links ]

QT Inc. v. Mayo Clinic. Jacksonville, 2006 US Dist. LEXIS 33668, at 10 (N.D. III. [ Links ] May 15, 2006).

Ribeiro, M. M. F., Krupat, E., & Amaral, C. F. S. (2007). Brazilian medical students’ attitudes towards patient-centered care. Medical Teacher, 29(6). DOI: 10.1080/01421590701543133.

Sari, M., Prabandari, Y., & Claramita, M. (2016). Physicians′ professionalism at primary care facilities from patients′ perspective: The importance of doctors′ communication skills. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(1), 56-60. DOI: 10.4103/2249-4863.184624. [ Links ]

Szwamel, K., & Kurpas, D. (2016). Analysis of the patients’ with minor injuries attendance to the Emergency Department. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review, 18(2), 155-162. DOI: 10.5114/FMPCR/59301. [ Links ]

Tarrant, C., Stokes, T., & Baker, R. (2003). Factors associated with patients’ trust in their general practitioner: A cross-sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice, 53(495), 798-800. [ Links ]

Thom, D. H., Hall, M. A., & Pawlson, L. G. (2004). Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Affairs (Project HOPE), 23(4), 124-132. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.124. [ Links ]

Thom, D. H., Ribisl, K. M., Stewart, A. L., & Luke, D. A. (1999). Further Validation and Reliability Testing of the Trust in Physician Scale. Medical Care, 37(5), 510-517. DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [ Links ]

Thom, D. H., Wong, S. T., Guzman, D., Wu, A., Penko, J., Miaskowski, C., & Kushel, M. (2011). Physician trust in the patient: Development and validation of a new measure. Annals of Family Medicine, 9(2), 148-154. DOI: 10.1370/afm.1224. [ Links ]

Vidal, C. E. L., Andrade, A. F. M., Mariano, Í. G. G. de F., Junior, J. S., Silva, J. C. F., Azevedo, M. D. O., & Morais, U. A. B. (2019). Atitude de estudantes de medicina a respeito da relação médico paciente. Revista Médica de Minas Gerais, 29(8), S19-S24. DOI: 10.5935/2238-3182.20190040. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade da Beira Interior, 6200-506 Covilhã, Portugal, email: filipeprazeresmd@gmail.com Tel.:234 393 150

Recebido em 26 de Maio de 2020/ Aceite em 16 de Junho de 2020