Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by hyperactivity, inattentiveness and impulsiveness that interferes with functioning or development (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000; American Psychiatric Associacion, 2003). ADHD is the most frequent neurobehavioral disorder among children, and can lead to numerous negative consequences in everyday life, including high levels of stress (Oster et al., 2020). Unpredictable situations and changes from the normal routine were stated to be common precursors of stress in this population (Oster et al., 2020; Reimherr et al., 2017). ADHD symptoms such as irritability, behavioral problems like aggressiveness and oppositional behavior are also often described as strong predictor to parenting stress (Craig et al., 2020), having parents of children with ADHD higher rates of stress and mental health difficulties than parents of typically developing children (Cheung & Theule, 2016; Martin et al., 2019; Schroeder, & Kelley, 2009; Silva et al., 2015).

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO), has declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). In Portugal, schools closed on March 13, forcing children to stay at home. Some of them started to get homework from their teachers on a daily basis, while others took classes using videocall. Furthermore, in an attempt to maintain the access to education universal and overcome inequalities, Portuguese Government began broadcasting classes through television (República Portuguesa, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a humanitarian challenge (Wagner, 2020), forcing families to adjust their lives, struggling with the fear of the disease (Shuja et al., 2020), social isolation, remote work and at the same time having to be “teachers” of their own children.

This study aims to explore how children with ADHD and their parents experience the isolation in their homes during school closedown in the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesised that parents of children with ADHD would report higher rates of stress and lower rates of adaptive capacity in regard to themselves and their children compared to parents of children without neurobehavioral disorders during this time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study focusing children with ADHD and their parents, in Portugal, during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Method

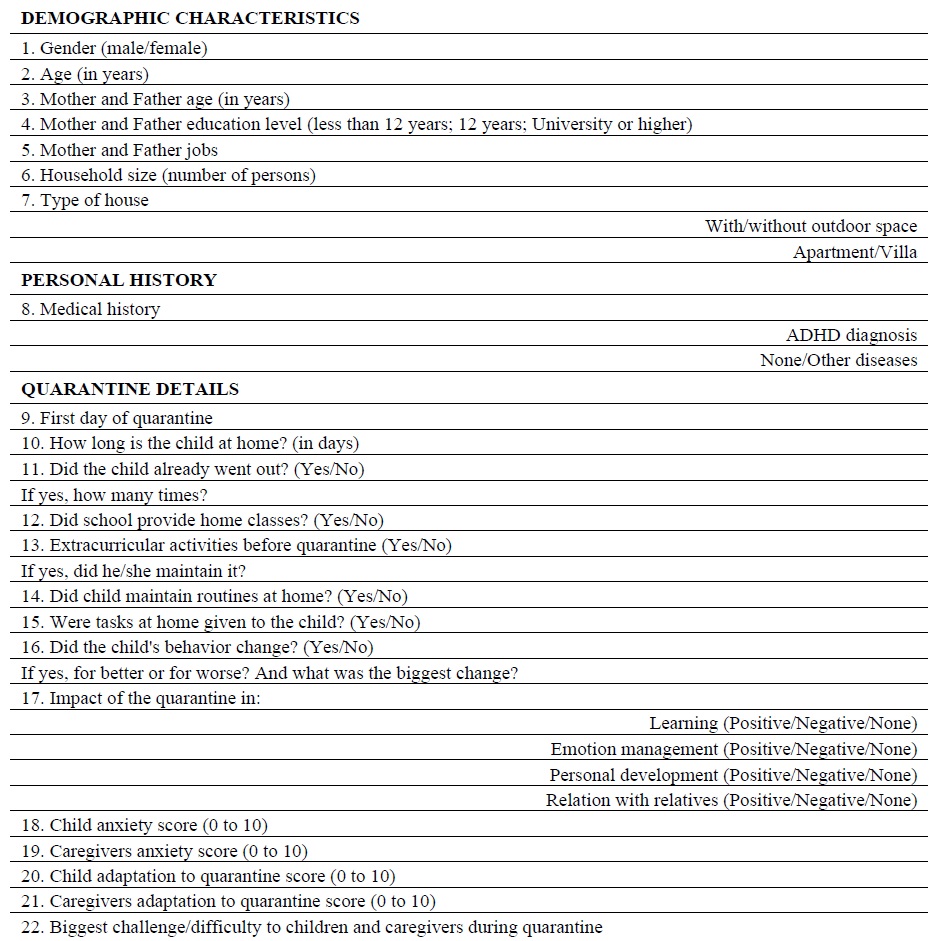

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional and analytical study. An anonymous questionnaire was designed where children’s demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as the impact of the quarantine in different aspect of theirs’ and their parent’s daily life were included, with a total of 21 groups of questions (Table 1). The variables “anxiety levels” and “adaptation to quarantine” were asked to be scored from 0 (no anxiety/inadaptation to the quarantine) to 10 (maximum anxiety/total adaptation to the quarantine).

Parents of 150 children with ADHD diagnosis, as well as 100 parents of children without neurodevelopment disease (control group) were contacted by telephone or by e-mail (through online form) during April 2020. Questionnaires related to parents who didn’t want to reply or didn’t answer phone calls were excluded, as well as questionnaires related to children younger than 6 or older than 18 year old.

Variable descriptive analysis was performed. This included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviations for continuous variables. Comparison between ADHD group with control group was performed using Student’s t-test and Chi-square. All reported values of p were two-tailed, with a 0.05 significance level (α). Data analysis was carried out using SPSS® software, version 24.

Results

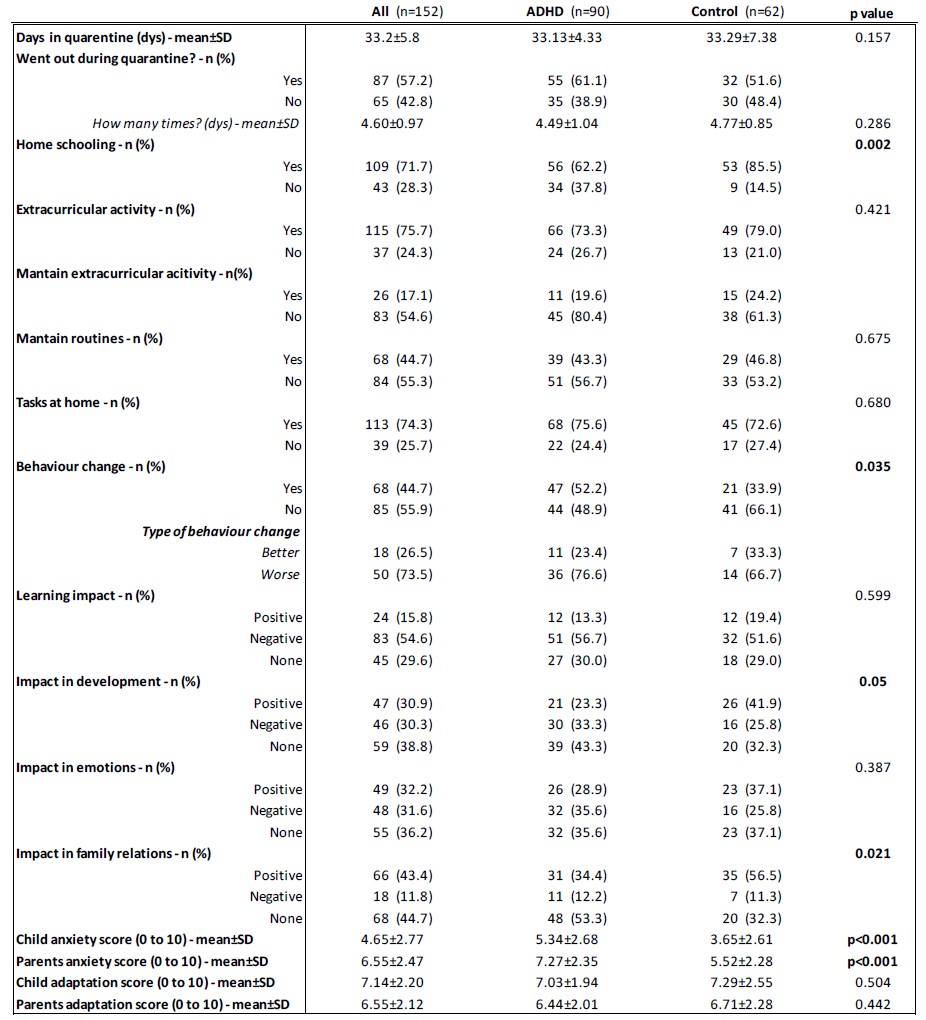

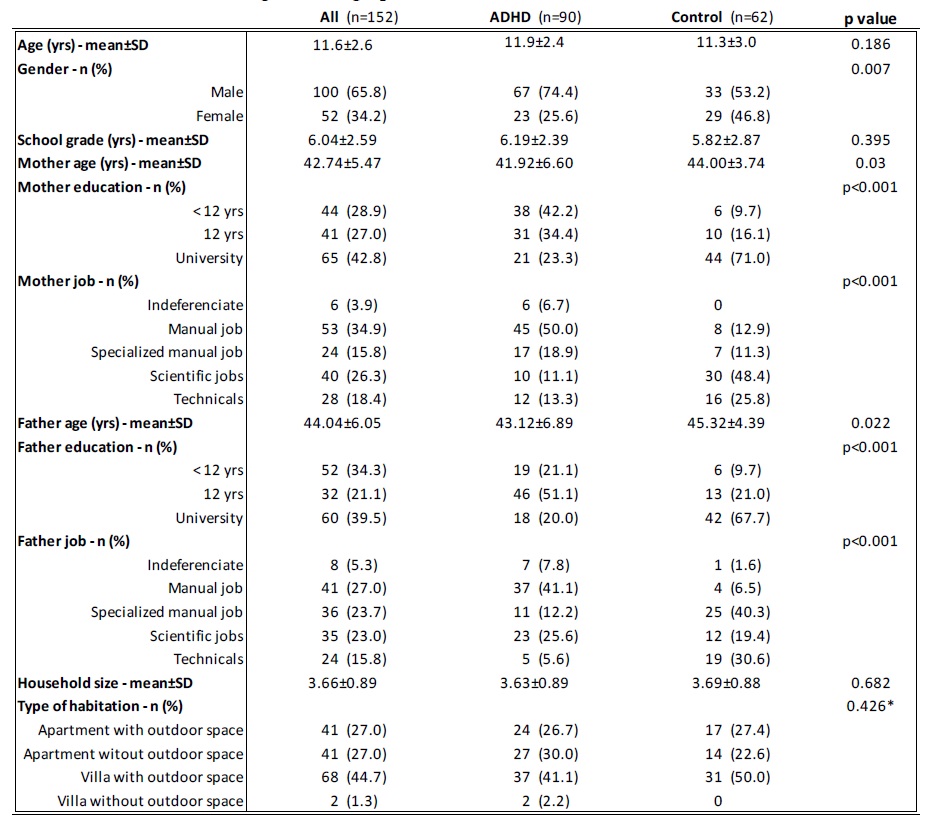

Among the 152 questionnaires obtained, 90 were related to children diagnosed with ADHD and 62 to children in the control group. Results respecting to demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Results concerning to demographic characteristics

*p=0.837 if both groups are compared considering houses with outdoor space vs houses without outdoor space

Mean age of all studied children was 11.6 (±2.6) years, with predominance of boys (65.8%). Parents were predominantly university educated (42.8% for mothers and 39.5% for fathers), and children were in average in their 6th grade (6.04±2.59 years). They mostly live in villas with outdoor space (44.7%), with a mean household size of 3.66 (±0.89) persons, and we found no statistically significant differences between both groups in these two variables (p=0.426 for house type and p=0.682 for household size).

Regarding most of the quarantine details results (Table 3), on average, all the investigated children were in quarantine day 33.2(±5.8) at the time of questionnaire filling, without statistically significant difference between ADHD and control group (p=0.157), and most children (57.2%) already went out at least one time during that period.

The great majority of children were provided with home school classes (71.7%), and there was a statistical significant difference in the proportion of providence between ADHD and control groups (62.2% in ADHD vs. 85.5% in control, p=0.002).

When asked if their children had changes in behavior, parents of children with ADHD predominantly agreed (51.1%), being the most frequently described changes in behavior anxiety and agitation, while parents of the healthy ones mostly found no changes (66.1%), and differences between these groups were statistically different (p=0.035).

Concerning to the quarantine’s impact in learning, both ADHD and control group’s parents reported mostly negative impacts (56.7% in ADHD and 51.6% in controls), and we found no statistically significant differences between the groups (p=0.599). We also found no statistically significant differences in the reports of the quarantine’s impact in emotion management (p=0.387).

On the other hand, the impact of the quarantine in personal development (p=0.05) and in family relations (p=0.021) was statistically different between ADHD and control groups, with the majority of parents of ADHD children reporting no impact in personal development (43.3%) and in family relations (53.3%) against those in control group reporting mostly positive impact of the quarantine in personal development (41.9%) and in family relations (56.5%).

In what concerns to the reported anxiety levels imposed by the quarantine, ADHD children had higher mean levels (5.34±2.68) than healthy ones (3.65±2.61) and the same occurred in caregivers of ADHD children (7.27±2.35) versus those of the healthy group (5.52±2.28). All these differences were statistically significant (p<0.001). We also highlight the fact that caregivers have higher mean scores of anxiety levels than their children.

Regarding to the ability of adaptation to the quarantine, we found no statistically significant differences in mean scores either in children (7.03±1.94 in ADHD group versus 7.29±2.55 in control group, p=0.504) or in their parents (6.44±2.01 in ADHD group versus 6.71±2.28 in control group, p=0.442).

A final word to the biggest challenges/difficulties reported by caregivers relating to themselves or to their children, which were, by far, the difficulty in monitoring home school and to deal with isolation.

Discussion

The most common impacts of an epidemic in children are anxiety, panic behavior and sleep disturbances (Jiao et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020). Currently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is given high warning to the physical health. Nevertheless, psychological health can’t be ignored (Brooks et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020; Lima et al., 2020).

ADHD is associated with social difficulties and emotion dysregulation (Classi et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2014; Teixeira et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2008) that can lead to conflicts with family. In our study, parents of children with ADHD reported significantly more changes in behavior and mostly no impact in family relations when compared to those in control group, while parents of the control group reported mostly a positive impact in family relations during quarantine. The most frequently described changes in behavior was anxiety and agitation. A study from China (Zhang et al., 2020) focusing children with ADHD during the COVID-19 outbreak also showed that ADHD diagnosed children’s behavior significantly worsen comparing to their normal state and that parent’s mood also impact children’s symptoms. In our sample, the impact of the quarantine in emotions seems to be equivalent between both groups, and this could be related to the fact that, during quarantine, ADHD children’s don't have to deal with school demands, rules, and high social pressure, often seen as a major challenge in this group (Chen et al., 2020; Classi et al., 2012; Hartman et al., 2019; Oster et al., 2020; Rushton et al., 2020). Furthermore, the increase in the consumption of videogames and screens was frequently reported by the parents during this period.

Negative impact in learning were reported by the parents of both groups with no statistically differences, what supports the theory that school closedown is a serious challenge to everyone, even in healthy and without neurodevelopmental impairment children (Shuja et al., 2020; Wagner, 2020). In addition, most parents pointed out the difficulty in monitoring home school as the biggest challenge they face during quarantine.

Although there are few published studies on this subject, some researchers have stated that children who are quarantined may be experiencing high levels of stress and are vulnerable to develop serious mental abnormalities (Jiao et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). A study conducted by Moccia et al., 2020, on the Italian general population during COVID-19 pandemic, showed that 38% of the individuals reported mild or moderate-to-severe psychological distress. Cao et al., 2020 also exhibited that 24.9% of student’s sample from a Chinese college experienced anxiety due to COVID-19 outbreak. Indeed, in our study, children with ADHD and their parents had higher levels of stress/anxiety than healthy ones during the outbreak, suggesting that both children with ADHD and their caregivers may be a risk group to pay attention to, in what concerns to psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interestingly, caregivers of both groups reported higher stress levels in themselves compared to their own children. This information should alert physicians to the importance of red flags’ recognition, not only in children but also in their parents, as well as strategies’ provision to the whole family to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak. In this subject, we highlight that The International Paediatric Association provided guidance for physicians to manage children’s health during COVID-19 (Klein et al., 2020). Likewise, WHO, UNICEF and others have developed guidance for support families to stress management including ways to explain the pandemic to their children (Healthy Children, 2020; Save the Children, 2020; US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; UNICEF, 2020; WHO, 2020).

Nonetheless, our study has also some limitations. The data collected online through email sent questionnaire, which was mostly answered by parents of healthy children, may have a bias of a higher graduated population and possibly with greater capacity for coping strategies. Additionally, all data were reported by parents rather than reported by children directly.

In conclusion, the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health have not been studied systematically, yet our results alert to the importance of focusing on special vulnerable groups and to the post-pandemic investigation of mental disorders among families.