Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) individuals in Portugal currently enjoy an unprecedented degree of political and social acceptance with a positive impact in their everyday lives (reference removed to allow anonymous review), such as the introduction of a non-discrimination clause on the basis of sexual orientation in the Portuguese Constitution in 2004, the 2010 law allowing same-sex couples to marry, the 2016 law allowing same-sex couples to adopt and joint-adopt children, and the 2018 self-determination law on gender identity and intersex children, making the country rank in the top 7 European nations in respect to human rights and full equality for LGBT people (Rainbow Europe, 2019). The LGBT movement has played a crucial role in influencing legal changes in respect to individual claims in Portugal, however, the identity development of LGBT individuals is still restricted by negative societal attitudes, which generally result in the internalization of the stigma associated with their sexual or gender identity (Costa et al., 2013) or in negotiating the impact of discrimination on their mental and physical health (reference removed to allow anonymous review). This could be particularly the case for more vulnerable groups of LGBT individuals such as LGBT youth.

In fact, LGBT youth face a unique set of challenges each day in Portugal, such as bullying or harassment (Rodrigues, Grave, Oliveira, et al., 2016), or 3-4 times higher suicide behavior rates than that of their straight counterparts (reference removed to allow anonymous review). Other studies with LGBT youth have covered different topics when working with this population such as: victimization (Marx & Kettrey, 2016), religious and spiritual identification (Meanly et al., 2016), foster systems (Salazar et al., 2019), psychological resilience (Grossman et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2016), identity management strategies (Schmitz & Tyler, 2018), psychological distress (Flaskerud & Lesser, 2017), and mental health (D’Augelli, 2002; Russel & Fish, 2016), all focusing on the vulnerability statue due to communal factors such as identity consolidation and coping with minority stress.

Advances in law and policy in Portugal have helped lead to much more fulfilling and productive lives for many LGBT persons, but the problems facing LGBT youth in Portuguese society are still to be documented. There is a paucity of relevant scientific research in this field and the construction of a narrative associated with the meaning of being LGBT youth is a complex, multifaceted effort, accommodating multiple possibilities and paths; these may include dealing with homophobia, establishing meaningful relationships and understanding the concerns of identity management, and keeping resilience and social support as key aspects. Uncovering the psychosocial dynamics of LGBT youth in Portugal will allows us to better understand the prevention needs and adjust interventions. Articulating such issues and giving voice to LGBT youth in Portugal is a primary goal of this study. We correspondingly adopt a qualitative approach, made even more important, given that, to our knowledge, there are no studies on this subject in Portugal.

Methods

Design and Procedures

With qualitative research methodology, this study used purposive sampling techniques (Patton, 1990; Palinkas et al., 2015) to recruit a final sample of 29 LGBT youth from 16 to 27 years of age. The methodological bases for this qualitative study was the identification of sources of oppression and the interpretation of content relating to what it means to be young and nonheterosexual or cisgender, according to Meyer’s minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003).

Information about the study was disseminated through Portuguese LGBT associations and community centers (such as Rede Exaequo - the National LGBT Youth Association, the International Lesbian and Gay Association-Portugal, Opus Gay Association, and others), as well as through mailing lists and social networks (e.g., members of nongovernmental agencies and organizations that work with LGBT people, internet forums, and Facebook). Participants responded to this outreach online by way of a website created for this purpose. Following the study description and the clarification of the objectives of the research, participants were asked to read and agree to informed consent and acknowledge their voluntary participation, including issues of confidentiality.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: self-identify as LGBT, live in Portugal, speak Portuguese as their mother tongue, and be from 16 to 27 years of age. All of those who responded were invited to complete a structured inquiry consisting of a short section of sociodemographic questions (e.g., age, education, place of residence, who lived with and sexual orientation and/or gender identity disclosure) and another section with questions designed according to the study main topics and objectives. A set of 10 open-ended questions was developed by the author to guide the electronic data collection process. These included the following: As a young LGBT person, what are your main obstacles/difficulties in your life? What are your main advantages/facilitators in your life? What type of support do you think it’s more important for you? What do you think it’s important for other people (parents, educators, health professionals, etc.) know about you? How is your health? How is your social network? What are the main differences when comparing your generation with older generations? How does your sexual orientation/gender identity influences (or not) your happiness and wellbeing? How do the political and legislative changes affect your everyday life? What is the impact of homophobia/transphobia in your life?

Participants

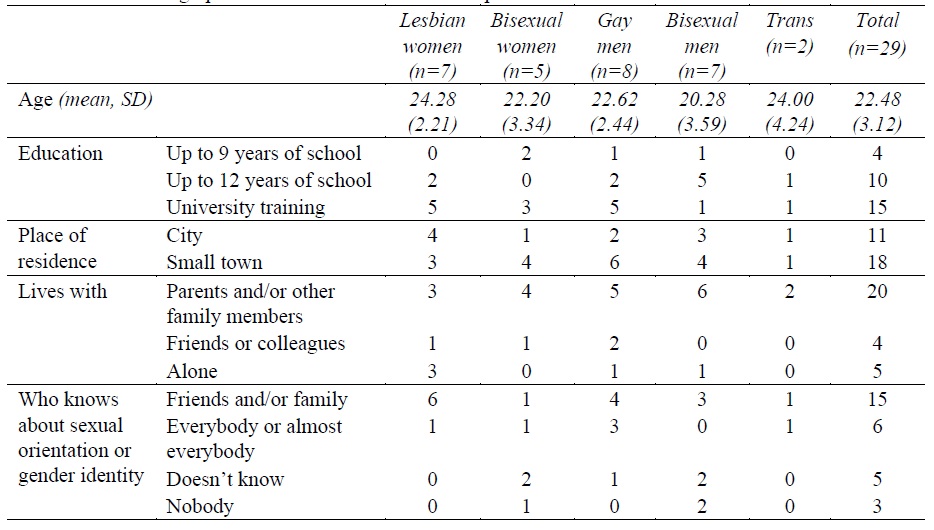

Of the total of 320 initial electronic contacts, 29 LGBT youth fully responded to the two questionnaire sections and comprise the sample for these analyses. These participants had an average age of 22.48 years (SD=3.12), ranging from 16 to 27 years. In Table 1, we describe in greater detail all sociodemographic information of the 29 participants in the study.

Data Analysis and Tools

The data consisted of the direct transcriptions imported from the information provided by participants in the electronic questionnaires. We used thematic analysis to identify repeated patterns of meaning through the data sets. Thematic analysis is not tied to any specific theoretical framework and can be applied to various theories and methodological approaches (Joffe, 2011). Having successfully been applied to other studies in the area of critical psychology and social sciences, thematic analysis was assumed as inductive and data were obtained from the semantic content and latent constructs inherent to the texts of the participants (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Several steps were involved in this process, namely: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report.

The questionnaire answers were systematically analyzed by the authors allowing analysis through a constant comparison process of the recurring themes and the range of variation and nuances of each participant’s responses (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Consistency of coding was assessed by comparing codifications by two experts in psychology independently. In the cases where codifications did not match, the two independent coders engaged in a discussion in order to reach a consensus.

Results

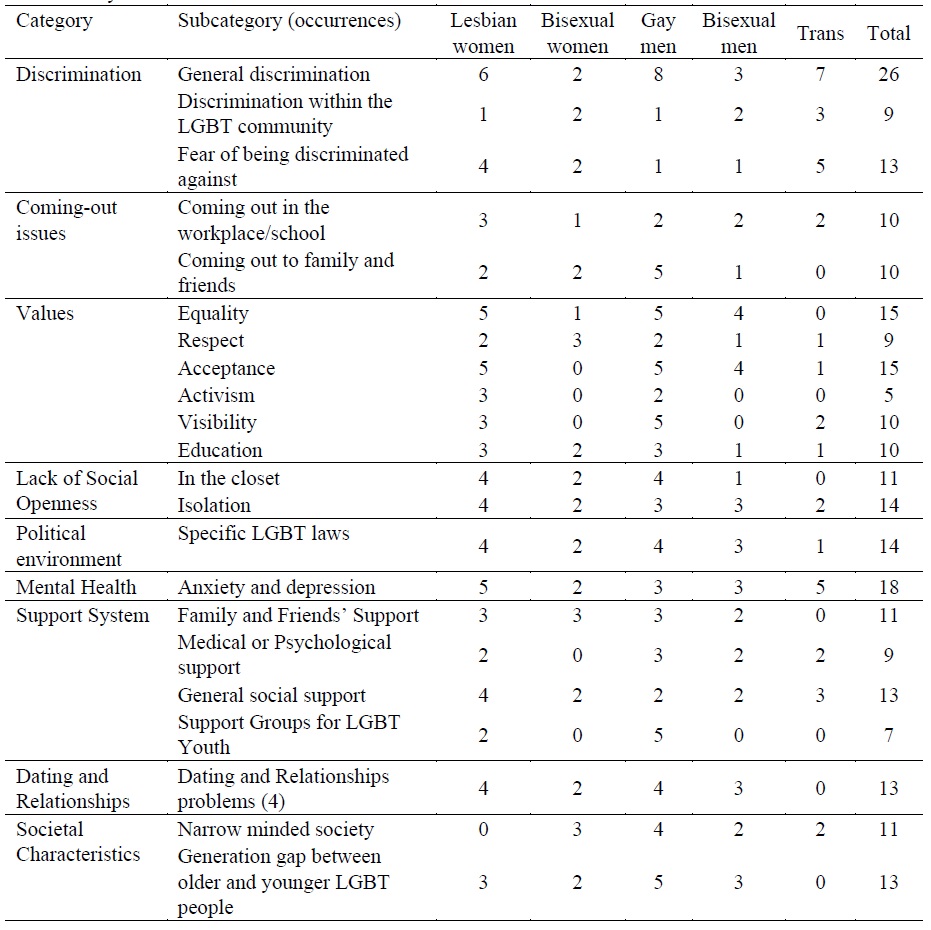

The content analysis of 29 participants’ responses revealed 9 overarching themes (categories) encompassing 22 subcategories, as represented in Table 2. Results are shown comparatively between participants who self-identified as lesbian women, bisexual women, gay men, bisexual men and trans.

The following are descriptions and discussion of results, providing illustrative quotes from our participants.

Discrimination

Although there is, at present, greater social openness and legal rights for LGBT Youth in Portugal, it became clear that most of our participants show major concerns about discrimination, emphasizing the possibility of being discriminated against by society at large, within the LGBT Community specifically and also within their family; fear of discrimination is a likely contributor to emotional distress among LGBT youth (Almeida et al., 2009), as reported by one participant:

There’s still lots of prejudice everywhere, even from the people who live under the same roof. The fact that people still gaze at you on the streets, reflects a lack of total acceptance, which is very sad for me and my girlfriend. Sometimes we listen to comments when we hold hands or show affection in public spaces. But what really bothers me is the fact that I sometimes feel judged by other members of my own community, such as gay or bisexual men. Shouldn’t we all stand together united for a society without discrimination? (Joana, 19 years old, bisexual woman).

Coming-out issues

Many of our participants mentioned that one of the major issues they face has to do with the coming out process, both at school/workplace and at home (family and friends), despite the fact that most of them say that they are out of the closet. In fact, the formation of an LGBT positive identity is not easy for most people, especially youths, since many can anticipate some form of rejection (reference removed to allow anonymous review). In coming out models, integration of the LGBT identity is related to self-acceptance and community integration, but many of our participants describe a more subjective view of this process, emphasizing on their individual responsibility:

Coming out as a young gay man was the best thing that ever happened to me. I finally came out of the dark ages, felt confident about my whole identity, and was able to come out to some teachers, friends, and family members. Their reaction was like: “OK”, and that also helped me normalize who I was and feel less different (João, 20 years old, gay man).

Affirming my gender identity to all the important people in my life without fear, even if I had to deal with lots of judgement and lack of understanding and support, means that I don’t have to hide anymore and that is the difference between being alive or being dead (Maria, 22 years old, trans woman).

Values

Thriving through a society that can, at times, be seen as an adverse environment, may not always be an easy task but, on the other hand, may constitute an opportunity for personal development and growth. In fact, many of our participants mentioned significant personal gains that contributed to a sense of integrity, identity and pride. Since personal values can influence attitudes and behavior, especially at this stage of development, it was very interesting to observe their referring to values such as equality, respect, acceptance, activism, visibility or education, all integrated in a major perspective of human values.

“I think that the most important thing that we can have in our lives is respect. Respect for who I am as person, and as a gay man. If we don’t have respect, society will fall apart” (Daniel, 18 years old, gay man).

“Years ago, it was a lot harder to be an LGBT person, because there was more discrimination. If we have a more open society today (even if things are far from being perfect), it’s because there is more acceptance, and this acceptance comes from activism, from people not being ashamed of their identities and not being afraid to speak up. This also creates the necessary visibility and the legitimation of proper sex education in schools, that portraits social reality in an equal perspective“ (Leonor, 24 years old, lesbian woman).

Lack of Social Openness

Being in the closet and isolated as forms of defense mechanisms against possible social discrimination and rejection are still mentioned by some participants. This is a reflection of how Portuguese society, despite the fact that is politically inclusive and fair, proves inefficient to protect all members, including LGBT youth, and this can create many challenges, obstacles and may even lead to anxiety, depression and suicide (Adelson et al., 2016). Also, this seems to be more the case for bisexual and trans youth (Wilson & Cariola, 2019).

“In my case, I feel that my fear of being out to my family and friends is greater than being in the closet. I cannot deal with the anxiety I feel to show who I really am as a bisexual man, since I guess no one would really understand me and they would immediately start pressuring me whether to be straight or gay. Most people would describe being bi as jumping around from bed to bed, whether with men or women. I find this unfair and reductive of my personal experience, hence, I choose not to talk about it to anyone and live my life in the shadows” (Ricardo, 22 years old, bisexual man).

“I am still dealing with the process of being a young trans woman, everything is still very new to me, sometimes I face doubt, and other times fear. I isolate myself from society hoping that the fear will go away. It doesn’t” (Carla, 23 years old, trans woman).

Political Environment

Political and legislative changes in several countries in Europe, and in Portugal in particular, occurred due to a combination of circumstances such as: historical and cultural backgrounds, media or social trends, and the influence of LGBT movements. Although tackling exclusion in the member states of the European Union has been an objective since the launch of the Lisbon Strategy in 2000, the political environment regarding sexual minorities in Portugal currently shows an unprecedented degree of accommodation of LGBT persons’ needs, including marriage, adoption, and gender identity laws. This creates a very positive impact on the lives of LGBT youth in Portugal, but some participants say that this is not enough and that more specific laws to protect sexual minorities should also be implemented.

“Of course, that having equal laws is great, but they are not a gift. Rather, they are the recognition of a fundamental right: the right to equality. We need more energy and political will to change social mentalities” (Tiago, 25 years old, gay man).

Mental Health

Due to the existence of some levels of stigma, discrimination and victimization, LGBT youth face particular challenges in society. Anxiety and depression are reported as causes of LGBT youth morbidity and mortality across the world (Adelson et al., 2016), and this is also the case in Portugal (references removed to allow anonymous review).

“I don’t feel free to love and show my affection in public spaces, I feel constrained, and that makes me feel sad and angry. Feeling constantly worried that I could be rejected for being who I am, brings me a lot of anxiety and sadness. It didn’t have to be this way” (Diogo, 20 years old, gay man).

“I feel a lot of pressure. I have to be a good student, I have to be a good daughter, I have to be a good citizen, I have to be a straight woman… And I am not any of that. I just want to be who I am, and not feel depressed all the time” (Liliana, 17 years old, lesbian woman).

Support System

Having formal systems of support, especially family and friends, seems to be of utmost importance for LGBT youth and this is consistently related to higher self-esteem and lower depression (Watson, Grossman, & Russell, 2019). Also, this can be particularly the case for trans youth, since positive gender-supportive relationships have been found to promote their global well-being (Alanko & Lund, 2019).

“I feel very blessed for having the support of my family and friends. I know several cases of LGBT young people that, unfortunately cannot say the same. I believe that this has to do with the fact that my family is open to diversity, we talk about everything and my friends also respect my sexuality, even though I am the one who doesn’t always feel comfortable to do so. Sometimes I prefer to discuss my sexuality with other LGBT friends when I have the chance” (José, 21 years old, gay man).

“I feel very abandoned by my family, I think that they are ashamed of my gender identity. We hardly speak. Luckily enough, I found support in some friends and in my professional team, doctors and psychologists who accompany me in my transition period. If I didn’t have them around me, I’m not really sure what would happen to me. They keep telling that I am a valuable person, and I am starting to believe them” (Maria, 22 years old, trans woman).

Dating and Relationships

Dating and Romantic relationships are common topics addressed by LGBT youth, and our participants reported specific problems, usually involving sexual risk and protective behaviors, improving communication, coping with family and relationship violence, and the lack of role models and sources of support (Greene et al., 2015). Also, there is a need to include social media as potential sources of youth hookup culture and dating (Lykens et al., 2019). These were especially mentioned by lesbian and gay participants.

“Finding a boyfriend really is a difficult task, perhaps impossible. Dating apps are places for hookups, period. If you want to find someone for a significant relationship that is virtually impossible. So, many times, I start by the easy part (sex) in the hopes of finding a nice guy that wants to try something more than just sex” (Eduardo, 24 years old, gay man).

“Me and my girlfriend sometimes struggle with the fact that we do not always communicate effectively and this interferes with our levels of intimacy. Sometimes we don’t really know what we are doing. I never see any lesbian couples on TV, and sometimes I feel like an alien” (Luisa, 20 years old, lesbian woman).

Societal Characteristics

Although there is a reasonable level of societal approval enjoyed by the LGBT community, contemporary Portuguese society has just started to address the psychosocial meaning of what it means to be an LGBT young person or the consequences of the normalization of LGBT identities through legislation. Despite the political and legislative efforts to normalize LGBT identities, institutional heterosexism, interpersonal intolerance, and subjective ambivalence in Portuguese society still coexist with the tendency of political mobilization as a facilitator of the social inclusion of sexual minorities (reference removed to allow anonymous review).

“Portuguese society is still very narrow-minded. Of course, there’s lots of improvement when compared to older generations, but having laws that respect sexual minorities is not enough to eliminate prejudice, discrimination and bullying. We need to get to the core of society and change the way people think, feel and act in order to create a more open and inclusive society. Laws aren’t enough, we need more education programs and social interventions” (Francisco, 20 years old, bisexual man).

Discussion

Based on the presented dataset, it is consistently documented the presence of high levels of perceived discrimination against LGBT youth in Portugal in different settings, both the public and private sectors, indicating the need for further studies and social/political measures. According to the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), exposure to stigma and discrimination may result in negative outcomes in terms of mental and physical health, so future studies should include these variables. On the other hand, the existence of positive values and social support mechanisms available validate that the role of political and legislative measures in the lives of LGBT youth in contemporary Portuguese society does contribute to a safer psychosocial environment, allowing other possibilities in terms of sexual identity expression, such as the shifting of the psychosocial meaning of what it means to be an LGBT young person or the consequences of the normalization of LGBT identities through legislation (reference removed to allow anonymous review). The results of this study demonstrate that the political and legislative efforts to normalize LGBT identities have had considerable success despite continued institutional heterosexism, interpersonal intolerance, and subjective ambivalence in Portuguese society.

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of psychosocial dynamics of LGBT youth in a historic moment of global political equality in Portugal, that doesn’t necessarily reflect absence of prejudice and discrimination. That, in turn, influences LGBT youth’s psychosocial adjustment, suggesting the importance of social support from family and friends (Watson et al., 2016; Doty et al., 2010; school experiences (Kosciw et al., 2013; Day et al., 2019; Goldberg et al., 2019), reinforcing the importance of positive social environments in which LGBT youths live that may have a direct positive influence on their health and well-being (Gower et al., 2019).

This study is not without limitations. First, there was the potential for selection bias as the study was advertised in LGBT Youth oriented social-networking venues and as such did not capture those young people who did not frequent these places. Further research exploring the perceptions of these other groups of younger LGBT people would be useful. Given the qualitative nature of this study, future research should include bigger samples that could be more representative of the LGBT Youth population. On the other hand, most participants were well educated and from urban settings, which constitutes a threat to transferability of results. As this is a common problem in LGBT developmental research, it would be useful if future studies to include those LGBT young persons from a variety of geographic groups and educational backgrounds, as well as the use of complementary methodologies, such as: in depth face-to-face interviews, focus groups, or Research Action Plans. However, the intention of this study was not to generalize the findings to all LGBT youth, but, foreground the voices of this group so that their perceptions of the psychosocial dynamics after global political equality in Portugal could he heard.