Epidemiological studies indicate that Portugal has one of the highest rates of prevalence of mental illness in Europe. In 2016, one in five Portuguese suffered from a psychiatric disorder (Programa Nacional para a Saúde Mental, 2017). There are plans to set up mental health teams in each region of the country, but so far they have not occurred. The Cuidados Continuados Integrados [Integrated Continued Care] network in mental health is small, which is a major constraint for rehabilitation and support of responses to people with mental health problems (Ministry of Health, 2018).

The Conselho Nacional de Saúde [National Health Council, CNS] recommends that mental health teams need to have the essential resources to deliver services closer to people with mental health problems, together with other areas of social services and the community (CNS, 2019, p. 97). Furthermore, the Programa Nacional para a Saúde Mental [National Mental Health Program] (2017) also targeted 2020 to highlight the importance of further actions related to programs to promote mental health and prevent mental illness. As part of this, while most home support intervention teams include nurses and social workers, we believe that these multidisciplinary teams also should include psychologists and neuropsychologists who can provide more comprehensive interventions for other effects of chronic mental health conditions such as cognitive declines (Onder et al., 2012).

Cognitive decline in psychotic disorders has been documented over the course of the disease, showing impairments in cognitive functioning in persons with depression (Fedorová et al., 2017) as well as those with psychotic disorders (Zhu et al., 2019). These cognitive impairments have been documented in most cognitive domains, including memory, executive functioning, and attention. There are clinically significant deficits in many cognitive functions after the first hospitalization for psychosis (Fett et al., 2020). Fett et al. (2020) suggests that cognitive aging in some areas may be accelerated in individuals with psychotic disorders; that is, in patients who been admitted for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, a 20-year follow-up revealed greater cognitive impairment relative to age matched peers. Thus, there is support for the importance of focusing interventions on cognitive functioning in patients with psychosis even after acute psychotic symptoms have improved.

Within cognitive abilities, executive functions seems to be of particular importance in the case of mental health problems, as they seem to be notably important for psychosocial functioning and for performing instrumental activities of daily life (Lezak et al., 2012). It also has been shown that subjects with deficits in executive functions have been considered more vulnerable to the development of mental disorders including psychosis (Johnson, 2012; Orellana & Slachevsky, 2013).

Many studies have supported the effectiveness and accessibility of home-based interventions in persons with chronic mental health illnesses. Borson et al. (2019) conducted home-based psychotherapy sessions in older adults and adult caregivers for treatment of depression and anxiety, reaching 211 subjects from 2015 to 2018. In the study by Werbeloff et al. (2017) in the United Kingdom, crisis intervention teams were successful, including in non-affective psychosis patients with one-off interventions in borderline situations. In Germany, Sakellaridou et al. (2018) developed assertive community and at home interventions over 24 months in persons with multi-episode psychosis, obtaining significant improvements in quality of life (overall functioning), as well as a decrease in the number of hospital admissions. Landers et al. (2016) defined some strategies for the implementation of home-based health care in the US, with greater emphasis on medical and nursing services.

In Portugal, the Samaritano project, a home-based intervention led by a team of nurses and psychiatrists, produced significant improvements in the quality of life of the participants with terminal illnesses (Teixeira et al., 2016). Thus, some studies have focused on case evaluation and intervention in specific and acute situations, but there are few published studies on continuous intervention in persons with chronic mental illnesses.

Home-based cognitive stimulation (CS) interventions have been successful in patients with dementia. A recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) using a reminiscence-based CS protocol found significant positive effects of the intervention on cognitive screening, memory, and quality of life scores in a Portuguese mixed NCD sample after 13 weeks when comparing those who received the protocol and those who did not (Justo-Henriques et al., 2021a). Similarly, this protocol has shown positive effects on memory, executive functioning, and quality of life when examining this protocol in a sample of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) patients (Pérez-Sáez et al., 2021). However, there is limited knowledge in how cognitive stimulation can help cognitive functining in chronic mental health patients, including those with psychosis. Thus, the current study will explore the effect of an individual home-based CS program on cognitive and mood functioning in adults with psychotic disorders.

Method

Design

A repeated measures design was used and all participants were referred by the psychiatric service of the hospital in their area of residence. The participants were evaluated at baseline before the intervention, with follow-up evaluations at four months and a post-intervention evaluation at eight months.

Participants

Participants were diagnosed with psychotic disorders as indicated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) through the psychiatry service of the Hospital of Aveiro, residents of the municipality of Albergaria-a-Velha. To participate in the study, the following inclusion criteria were defined: (a) adults over 18 years; (b) diagnosed with mental illness according to the criteria of DSM-5 (APA, 2013), determined by a professional clinician; (c) willing to participate in all intervention and assessment sessions; (d) provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: (a) presentation of a condition requiring immediate intervention (e.g., suicidal thoughts) or interfering with participation in the study (e.g., severe hearing deficit); (b) inability to communicate adequately, limiting participation in the intervention and proper use of materials, as determined by the therapist; (c) currently participating in another study.

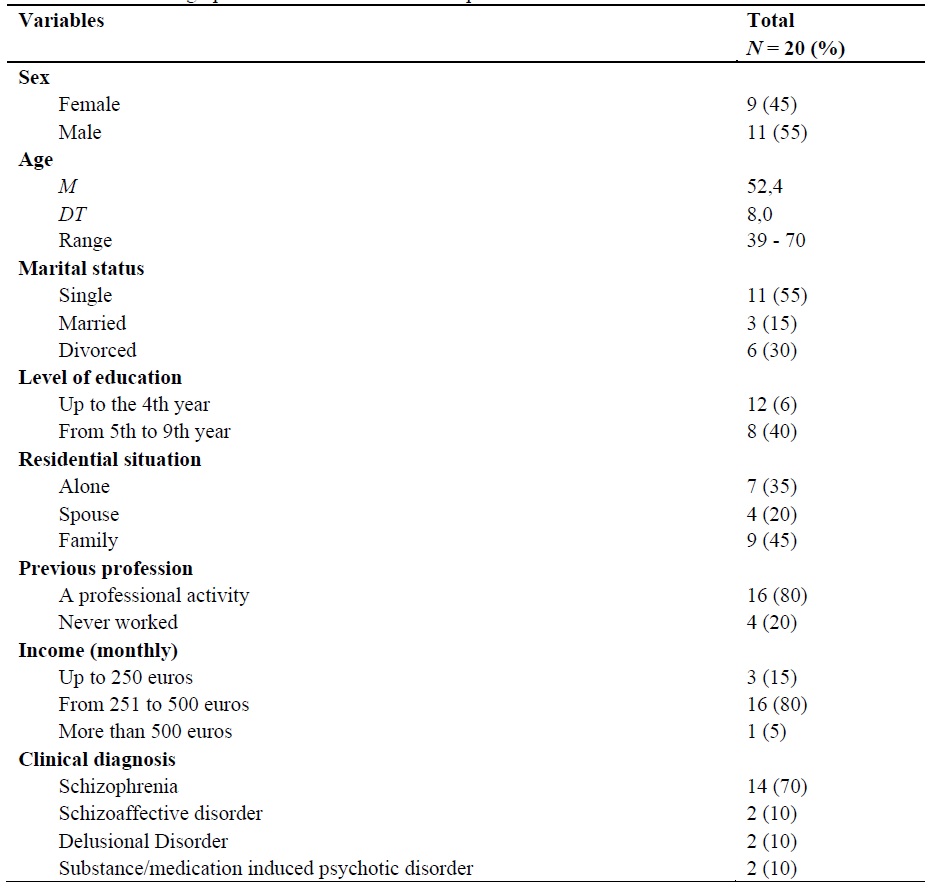

A total of 20 people met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were invited to participate in the study. The majority of participants were men (55%), single (55%) and with an average age of approximately 52 years. Regarding educational level, participants had mostly up to the 4th year. Regarding living situation, 45% lived with relatives, 35% alone, and 25% with a spouse. In terms of their previous profession, most had a professional activity and an income between 251 and 500 euros monthly. The most prevalent clinical manifestation was schizophrenia spectrum disorders with some meeting criteria for substance abuse (Table 1).

In this research, all the ethical-legal principles applicable to the scientific research were respected, in accordance with the latest revision of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki of 2013. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed in the processing and data analysis in accordance with current legislation. Participation was entirely voluntary, with no financial or other benefit to participants.

Instruments

The evaluation instruments were applied in three phases, pre-intervention (baseline), intra-intervention (four months) and post-intervention (eight months), by a clinical psychologist with more than five years of experience and previous training.

Demographics gathered included gender, age, marital status, educational level, cohabitation status, previous profession, income, and the etiological subtype of mental disorder.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] was used to assess cognition (Freitas et al., 2013; Nasreddine et al., 2005). Scores range from 0-30 points, with higher scores corresponding to better cognitive status. It is a frequently used and reliable instrument with good internal consistency (( = .90) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.87) (Duro et al., 2010).

To evaluate executive functions, the Frontal Assessment Battery [FAB] was administered (Dubois et al., 2000; Lima et al., 2008), which presents with sound Cronbach's alpha reliability of .78. Its score range from 0 to 18 points, with higher scores indicating better executive performance.

Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory II [BDI-II] (Beck et al., 1996; Campos & Gonçalves, 2011), one of the most widely used self-report instruments for the assessment of depression, with a Cronbach's alpha of .80. Score range from 0 to 63 points with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms.

To assess the level of acceptability and adherence to the intervention, the therapist recorded the attendance and behaviour of each participant on a form at the end of each session.

Procedure

The home-based individualized intervention took place between February and November 2019, and consisted of 35 sessions. It included three evaluation sessions (pre, intra and post-intervention), with sessions taking place weekly and lasting approximately 45 minutes. Throughout each session, the therapist followed the principles of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy, formulated by Spector et al. (2006). Our primary outcomes were cognitive functioning, specifically orientation, attention, memory, reasoning, calculation and language.

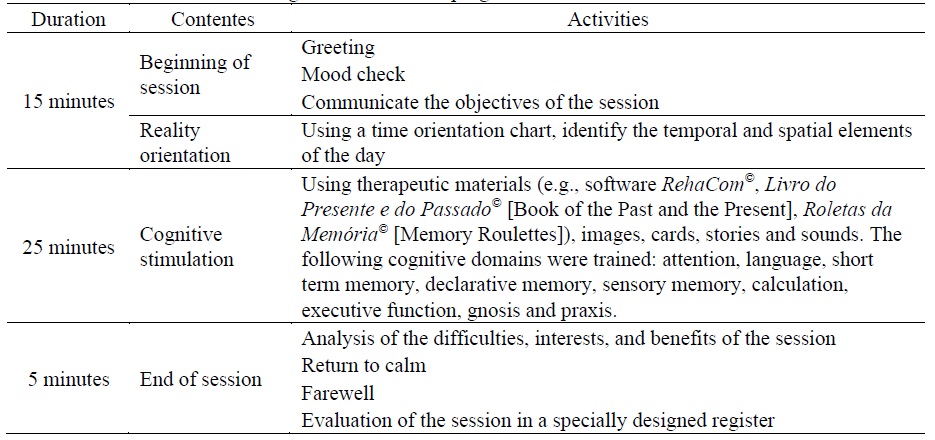

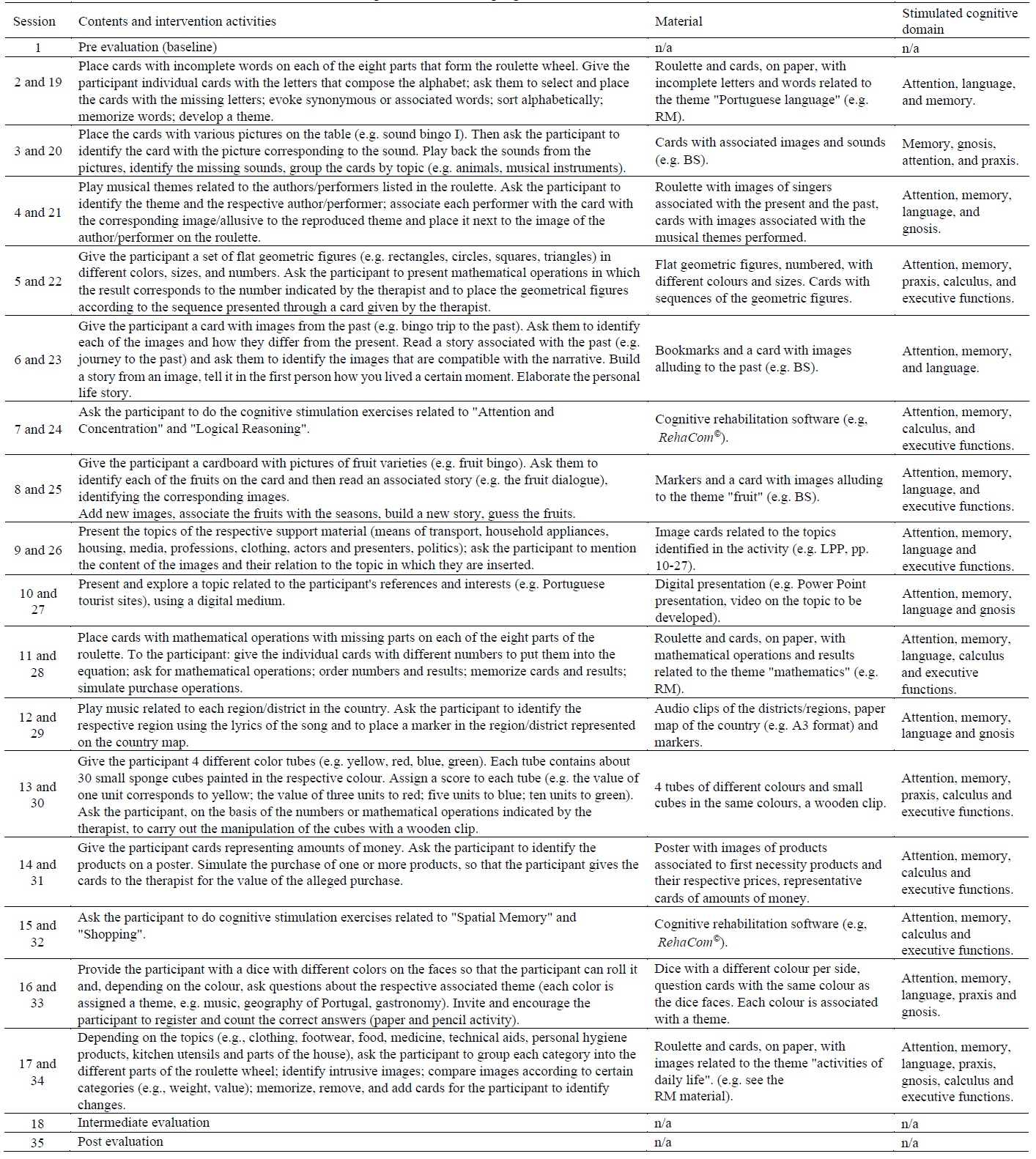

All sessions followed the same structure (Table 2) based on the model implemented by Justo-Henriques et al. (2019; 2021b; 2021c), with the introduction of complementary materials in the main activity. The first five minutes included introductions with the following 10 minutes dedicated to orientation towards reality, where the participant was encouraged to complete information regarding the date, current time, and location, through a time frame. Then, the main activity of cognitive stimulation was developed, lasting approximately 25 minutes, where the cognitive domains were stimulated using therapy and cognitive stimulation materials (Table 3). The last five minutes of each session were devoted to returning to a state of calm, with a brief relaxation exercise and a short discussion of the difficulties, interests, and benefits of the session. Finally, a farewell was held and the participant was reminded of the date for the next session. After the conclusion of the session, the therapist completed the evaluation form for the session.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences [SPSS, version 25.0]. To evaluate the effect of the intervention on cognitive status, depressive symptomatology and executive function at the three evaluation points (pre, intra and post-intervention), repeated measures ANOVA and pair-wise comparisons by with Bonferroni adjustment was conductred to compare the different evaluation moments. Cohen´s d (1988) was calculated as a measure of effect size for pairwise comparisons, with the following interpretation criteria: d = 0.2 (small), 0.5 (moderate), and 0.8 (large). The analyses were conducted in accordance with the intention-to-treat principle. Missing scores were replaced by the previous mean (imputation of last observation made). A significance level of 5% was assumed for all significance tests.

Finally, in order to know the percentage of dropouts, the level of adherence and the acceptability of the cognitive stimulation intervention program, the distribution of dropout frequencies and of participants who completed the intervention was analysed. Adherence to the program was also assessed by calculating frequency distributions and descriptive statistics of the sessions attended by participants. Finally, acceptability was evaluated by calculating the frequency distributions of the degree of collaboration of the subjects during the sessions and the preference of the participants in relation to the material used in the cognitive stimulation sessions.

Results

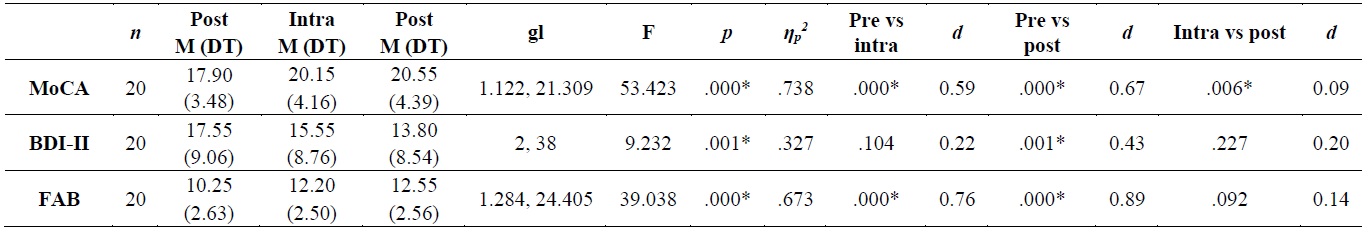

Table 4 shows the means of the outcome variables analysed at the three evaluation timepoints. Regarding the cognitive status assessed by the MoCA, ANOVA showed that the intervention had a significant effect, F(1.122, 21.309) = 53.423, p < .001, ηp 2 = .738, as scores improved in each consecutive assessment. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between pre and intra-evaluation (p < .001) with a medium effect size (d = 0.59), between pre and post-evaluation (p < .001) with a medium effect size (d = 0.67), and between intra- and post-evaluation (p = .006) with a small effect size (d = 0.09).

Table 3 Contents of the main activities of the individual cognitive stimulation program

Note: RM = Roletas da Memória © [Memory Roulettes]; BS = Bingos Seniores © [Senior Bingos]; LPP = Livro do Passado e do Presente © [Book of the Past and the Present].

Table 4 Means (and standard deviations) for each moment of evaluation of the instruments (results from repeated measurements and pair-wise comparisons [bonferroni adjustment] together with estimates of effect size [Cohen's D]

Note: BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II; FAB = Frontal Assessment Battery; Intra = Intra-intervention; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; Post = Post-intervention; Pre = Pre-intervention. *p<.05.Concerning depressive symptomatology (BDI-II), ANOVA showed a significant effect, F(2, 38) = 9.232, p = .001, ηp 2 = .327. In the pairwise comparisons a significant improvement was found from the pre to the post evaluation (p = .001) with a small-moderate effect size (d = 0.43), but not between the pre and intra-evaluation (p = .104), nor between the intra and post-evaluation (p = .227).

For executive functions (FAB), again the ANOVA showed that the intervention had a significant positive effect, F(1.284, 24.405) = 39.038, p < .001, ηp 2 = .673. Pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between pre and intra-evaluation (p < .001) with a medium-large effect size (d = 0.76) and between the pre and post evaluation (p < .001) with a large effect size (d = 0.89), but not between the intra and post-evaluation (p = .092).

Adherence and acceptability were good. There were three dropouts (15%) during the course of the intervention, two (10%) due to worsening health status and one (5%) due to disinterest in the intervention program. There were 525 sessions. Of the 35 sessions that made up the cognitive stimulation intervention program for each participant, the average attendance of participants was 26.3 sessions (75%). The 17 subjects who concluded the intervention carried out 503 sessions (85%). The main reasons listed for not attending the sessions were medical consultations and accompanying family members in unexpected situations.

Discussion

This study intended to evaluate the effectiveness of an home-based individualized cognitive stimulation program in participants diagnosed with psychotic disorders. After completion of the intervention, there was a slight but significant improvement in cognitive status and executive functioning as well as a decrease in depressive symptoms of the participants.

While the current study did not include a control group, we sought to understand to what extent the improvements in global cognitive function and executive functions presented in the post-intervention values in our study compared to mean values in different studies with normative data in healthy populations. In the post-intervention period, participants showed an improvement in cognitive status, with a medium effect size. These results are promising in comparison with other studies in the same area, which did not analyse the participants' cognitive status but found improvements in quality of life (Sakellaridou et. al., 2018; Werbeloff et al., 2017), as well as presenting median values similar to those of healthy populations (Ciesielska et al., 2016; Rossetti et al., 2011; Santangelo et al., 2015), and also effects above those of a cognitive stimulation program in healthy elderly women (Park et al., 2019). Nonetheless, our median values observed at all three time points were much less than those of a healthy population in a Swedish study (Borland et al., 2017).

Executive functions improved significantly after the intervention, with a medium to large effect size. No studies with a similar experimental design were found that have assessed executive functions, so these results are novel. Further, average post-intervention median values were found to be very close to those of healthy populations (Beato et al., 2007; Beato et al., 2012) but lower than those in other studies (e.g., Appolinio et al., 2005).

Regarding mood, there was a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in our sample, with a small-moderate effect size. This finding is consistent with other studies which also found a decrease in depressive symptomatology in individuals after attending an individual psychotherapy program developed at home (Borson et al., 2019).

In the comparisons between the three time points of the study, the improvement in cognitive status and the executive function is evident after four months of intervention, though, only depressive symptomatology continued to improve eight months following the intervention. In the study by Borson et al. (2019) in the home setting, a decrease in depressive symptoms was found after a 33-month intervention. These data underline the importance of long-term studies to verify the effect on participants' mood and justify the duration of the stimulation program used in the current study.

Considering the challenges associated with accessing mental health care in Portugal, and the fact that not all participants benefit from intervention models that are considered essential in the recovery of the subjects (Direção-Geral de Saúde [DGS], 2014), (including treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation programs), the current results suggest several benefits of the individual cognitive stimulation program in subjects with mental disorders. Particularly, improved cognitive status and decreased depressive symptomatology both can translate into a significantly increased quality of life for patients and their families.

The current study presents with many benefits and important clinical implications. First, highlighting the relevance of the study topic and the scarcity of research in this area brings to light the need for continued focus on this topic. Additionally, the creation of a standardized but adaptable and effective intervention program to the participants' situation is invaluable, particularly given the fact that the sessions are carried out at home and in individual format, with a wide range of cognitive stimulation materials available to the participant.

However, there are important limitations to note related to this study. This study had a dropout rate of 15%, though this may be justified by the nature of the psychiatric populations, including difficulties in the area of social functioning (i.e., low social skills acquired throughout life and no interaction outside the family context). As previously mentioned, the lack of a matched control group makes inferences more challenging. Additionally, cognition was evaluated using a screening instrument and as such the different cognitive domains were not evaluated in depth. The sample was of convenience and its size was small, which together with the fact that the study was developed only in the region of Aveiro makes it difficult to generalise the results. Finally, the lack of a follow-up period makes it difficult to verify whether the outcomes persist over time.

Initiatives covering mental health care at home are scarce, but the relevance and need for this type of cognitive stimulation intervention in people diagnosed with mental illness is becoming increasingly evident, as mental health teams intervening in the community context are “far from the acceptable minimum” (Joint Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2015, p. 59).

As mentioned above, there are variables that influence the median values in the MoCA and the FAB such as level of education, age, and acculturation. Since the median values in the present study shows an improvement in both instruments, from pre to post, and they can be compared with the ones from a normal population, we can conclude that the cognitive stimulation program undertaken can enchance global cognitive and executive functions in patients with a mental disorder.

This cognitive stimulation program can mitigate the cognitive loss of people with mental disorders and be beneficial in terms of mental health for the users. On the other hand, this study is a pioneer in the individual home-based format of interventions with this population applied by clinical psychologists. The high level of satisfaction with the intervention program proved to be important in a group of people with personality characteristics that stand out for difficulty in establishing social interactions outside the family support network.

Implications for research and clinical practice can be drawn from this study. It provides explicit information for planning a future randomised controlled trial (sample size calculation, sample selection, completeness of the study protocol) and evidence of the feasibility of the study.

Future studies should take into consideration the important limitations presented by the authors. Finally, it would be interesting to evaluate the effect of the program on relatives of people with mental health problems, as well as its effect on possible reduction in drug treatment and an analysis of associated health care costs.