With more than 296 million confirmed cases worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022), the infectious disease COVID-19 is transmitted primarily by nasal secretions or saliva droplets when the infected person sneezes or coughs (WHO, 2021). Most people experience mild to moderate symptoms, such as fever, dry cough, and fatigue, with no need for hospitalization (WHO, 2021).

Combating and controlling the COVID-19 pandemic requires the implementation of measures to break the chains of transmission, preventing associated diseases or even death (WHO, 2020b). Despite the effectiveness of these measures in delaying the disease spread, the pandemic has adverse consequences for the psychological health of individuals, along with the biological, economic and social impact.

Pandemic fatigue is one of these consequences, referring to the lack of motivation to adopt health protective behaviors and comply with preventive measures (WHO, 2020a). This phenomenon is accompanied by several emotions and cognitions associated with the exhaustion and overload of pandemic constraints (Order of Portuguese Psychologists, 2020). Research studying fatigue levels in the context of the pandemic crisis suggests that more than half of the individuals surveyed presented symptoms associated with pandemic fatigue, despite differences in methodology and samples under study. For instance, Teng et al. (2020) found that 73.7% of the participants in a sample of 2,614 Chinese frontline workers reported both physical and psychological fatigue. Morgul et al. (2020) found that 64.1% of the individuals in a sample of 3,672 Turks revealed physical and mental fatigue. In the study by Townsend et al. (2020) with a sample of 128 Irish COVID-19 patients, 52.3% experienced fatigue. Although it should be noted that these data must be interpreted carefully, as they do not result from a specific assessment of pandemic fatigue, but rather overall physical or psychological fatigue during the coronavirus pandemic.

Not only does pandemic fatigue threaten the adoption and maintenance of behaviors essential to fighting the pandemic, it can also be inferred from studies on fatigue in other conditions and populations that it is related to detrimental human health and functioning consequences. For example, a systematic review by Abrahams et al. (2018) demonstrates that higher fatigue in breast cancer patients is associated with lower biopsychosocial functioning, mental health and work productivity. It is also related to sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, distress, less physical activity, more pain, difficulties in coping with future health problems, and catastrophizing symptoms (Abrahams et al., 2018).

As a recent phenomenon, it is fundamental to have an assessment tool that provides detailed and rigorous knowledge about pandemic fatigue levels. To the best of our knowledge, the vast majority of studies on the assessment of pandemic fatigue have used previously existing scales, such as the Fatigue Assessment Scale by Michielson et al. (2003) and the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (Chalder et al., 1993).

The studies by Labrague and Ballad (2020), Lilleholt et al. (2020), and Seiter and Curran (2021) outstand for their application of the Lockdown Fatigue Scale (LFS), the Pandemic Fatigue Scale and the Social-Distancing Fatigue Scale (SDFS), respectively, developed for the specific purpose of assessing pandemic fatigue. Despite presenting good psychometric properties, these scales do not cover the multidimensionality of pandemic fatigue, and some do not even assess pandemic fatigue levels. For instance, while the LFS (Labrague & Ballad, 2020) only assesses cognitive-emotional components of lockdown fatigue, the Pandemic Fatigue Scale by Lilleholt et al. (2020) neglects this dimensions and focuses on the behavioral and information aspects of pandemic fatigue. Likewise, the SDFS (Seiter & Curran, 2021) measures burnout and tedium associated with social-distancing.

Since the study of pandemic fatigue is still at an early stage, little is known about the determinants of this condition. Daily and continuous exposure to pandemic-related news contributes to this state of tiredness and mental fatigue (Liu & Tong, 2020; Stainback et al., 2020). Bartoszek et al. (2020) found a positive correlation between social fatigue and time of isolation, insomnia, depression, and loneliness. Morgul et al. (2020) findings suggest that anxiety and fear arising from the coronavirus pandemic, as well as the isolation and mobility restrictions, are factors with associated negative psychological consequences. Increased screen exposure is one of the side effects of this isolation (Majumdar et al., 2020), with many people switching from face-to-face work to telework. In general, telework involves more effort (Palumbo, 2020), with the additional and more intensified work translating into higher levels of fatigue (Contreras et al., 2020). Moreover, Sagherian et al. (2020) and Zou et al. (2020) found that taking care of people infected with COVID-19 and dealing with illness worsening, respectively, was a trigger for fatigue. Self and others’ positive test result for COVID-19 is also positively associated with higher perceived risk (Nitschke et al., 2020) and significant levels of fatigue, especially in women (Townsend et al., 2020).

Likewise, little is known about the relationship between sociodemographic factors and pandemic fatigue, and the literature is inconsistent. Regarding sex, while some studies reveal that women experience higher levels of fatigue (e.g., Bartoszek et al., 2020; Labrague & Ballad, 2020; Teng et al., 2020), others did not find any significant association between pandemic fatigue and sex (e.g., Hou et al., 2020; Nitschke et al., 2020; Townsend et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020). Whereas some evidence suggests that younger people experience increased levels of fatigue (e.g., Lilleholt et al., 2020; Nitschke et al., 2020), others found no association with age (e.g., Hou et al., 2020; Townsend et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020). Labrague and Ballad (2020), Lilleholt et al. (2020) and Zou et al. (2020) found a correlation between lower levels of education and increased fatigue. On the contrary, Hou et al. (2020) did not find a significant association between education and fatigue.

This study aims to adapt and validate the Pandemic Fatigue Scale (PFS) based on the LFS (Labrague & Ballad, 2020). This research seeks to address the limitations found in the literature by adapting LFS’ items (referring to lockdown) to the pandemic context in general, reflecting the full scope of cognitive and emotional components of pandemic fatigue. In addition, this study intends to characterize a sample of Portuguese adults’ pandemic fatigue levels and explore its’ COVID-19-related determinants, including telework, being in either isolation or quarantine, period of confinement, positive test result for COVID-19 (self and significant others), telework-related fatigue, and the impact of COVID-19 news.

Method

Participants

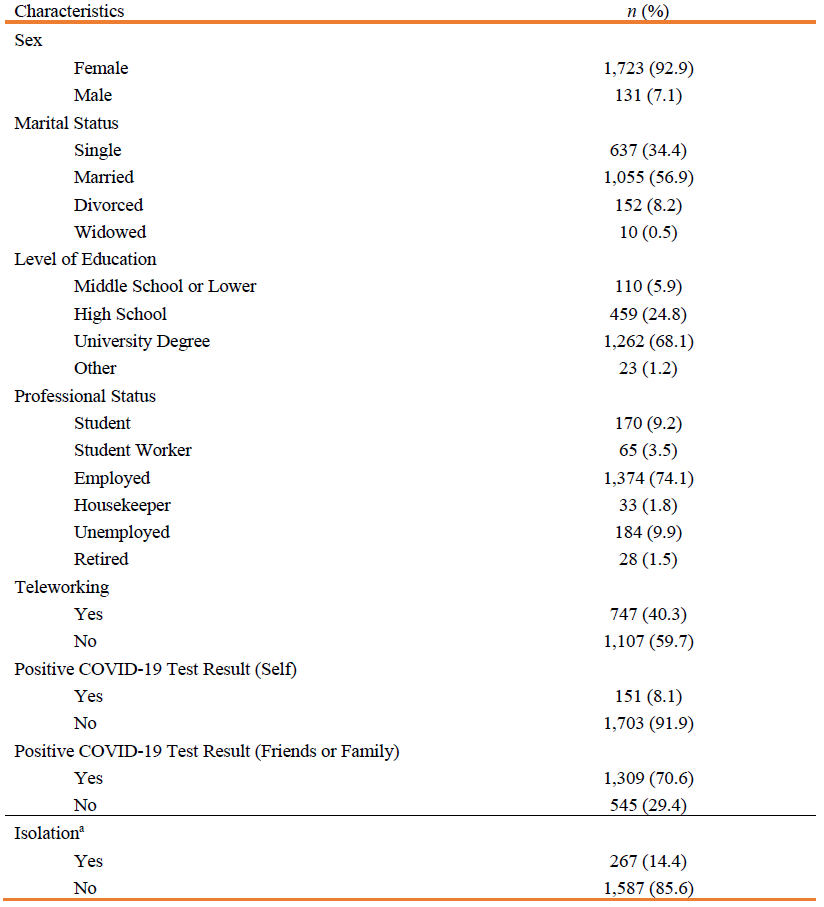

A total of 1,863 Portuguese participants were recruited online through convenience and snowball sampling, but only 1,854 were included in this study, since nine were underage. Participants are aged between 18 and 75 years old (M = 37.73; SD = 10.86). Participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Participants’ Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics (N = 1,854)

Note: a Participants were asked if they were quarantined either because they had tested positive for COVID-19 or had been in contact with someone who tested positive.

Measures

Pandemic Fatigue

The PFS, developed based on Labrague and Ballad’s (2020) LFS, is a 10-item self-report questionnaire which assesses cognitive-emotional components of pandemic fatigue (e.g., “I have thoughts that this pandemic will never end soon”). Respondents are asked to answer on a Likert-type scale ranging from never (1) to always (5) how often they experienced each of the statements presented during the pandemic. Scores can range from 1 to 50, indicating low (≤12), mild (13-25), moderate (26-37), and high or severe (38-50) pandemic fatigue (Labrague & Ballad, 2020). Although the authors propose that the scores range from 1 to 50, we suggest that it ranges from 10 to 50, since responses were requested for all items. The original LFS evidenced good internal consistency (α = .84) (Labrague & Ballad, 2020).

Sociodemographic and Pandemic-Related Questionnaire

A questionnaire was applied to collect participants’ sociodemographic (e.g., sex, age, marital status) and pandemic-related data, namely, telework, positive test result for COVID-19 (self and significant others), being either in isolation or quarantine, telework-related fatigue, negative impact of COVID-19 news, and period of confinement (i.e., partial confinement, from November 25, 2020, to January 20, 2021, and full confinement, from January 21 to February 19, 2021).

Procedure

After receiving permission from the authors, the original items of the LFS were translated independently from English to Portuguese by two Psychology students fluent in English. The two versions were compared and discussed, resulting in a consensually agreed version. Subsequently, an independent backtranslation was performed by another person fluent in English. The phrase “as a result of this lockdown” in items 3 and 6 was replaced by “as a result of this pandemic”. A pre-test was conducted with five individuals. The sentences’ original meaning and structure, as well as sensitivity to cultural adjustment, were considered during the process.

The survey link was disseminated online from November 25, 2020, to February 19, 2021 (during the second and third national waves of COVID-19), via social networks (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, LinkedIn), using a snowball sampling procedure. Informed consent was obtained from participants, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured. This research is part of the PsiQuaren10 project and was approved by the ISPA Research Ethics Committee.

Data Analysis

Data were exported from Google Forms to Microsoft Excel and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics and SPSS AMOS (v. 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Based on the authors’ proposed categorization, a categorical variable was computed from the sum of the PFS scores, and descriptive statistics were performed to characterize participants’ levels of pandemic fatigue.

Sensitivity of PFS items was evaluated through the analysis of minimum and maximum values, and skewness and kurtosis coefficients, which must present absolute values less than three and seven, respectively (Kline, 2005).

Factor validity was estimated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the maximum-likelihood estimation method. The local model goodness of fit was assessed based on the standardized factor weights (≥ .50) and items’ individual reliability (≥ .25) (Marôco, 2014). The global model goodness of fit was assessed according to the following goodness-of-fit indices and their reference values (Marôco, 2014): standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; < .08); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; < 0.05 good and < 0.10 acceptable fit) with 90% confidence interval (CI); comparative fit index (CFI; ≥ 0.90); Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; ≥ 0.90). The model was refined by excluding items with inadequate standardized factor weights (Marôco, 2014). Theoretical considerations were taken into account during the model refinement process.

Convergent validity was analyzed through the average variance extracted (AVE; ≥ .50) (Marôco, 2014). Internal consistency was estimated with composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha, which must be equal to or higher than .70 (Marôco & Garcia-Marques, 2006).

After confirming good psychometric properties of the measurement model, structural equation modeling was used to examine the role of COVID-19-related factors in predicting pandemic fatigue. The structural model fit was estimated based on the goodness-of-fit indices above-mentioned, standardized regression coefficients and items’ individual reliability, and causal paths’ significance given by a Z-test to the critical ratios. The level of statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Validation of the Pandemic Fatigue Scale

Sensitivity

According to Kline (2005), all items presented good psychometric sensitivity, with absolute values of skewness (-1.15 < Sk < 0.09) and kurtosis (-1.02 < Ku < 0.56) below 3 and 7, respectively, and responses ranging from 1 to 5.

Factor Validity

As shown in Figure 1, all items presented adequate standardized factor weights (.56 < λ < .88) and individual reliability (.32 < r 2 < .78), with the exception of item 1 (λ1 = .29; r 2 = .08). Goodness-of-fit indices indicated a good adjustment of the original factor structure to the data (SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.08, p < .001, 90% CI [0.08, 0.09]; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95).

Since it was a poor manifestation of the latent factor, compromising local and global fit, item 1 (“I worry a lot about my personal and family’s safety during this pandemic”) was excluded. Figure 2 shows that the refined model fit improved slightly (SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.09, p < .001, 90% CI [0.08, 0.10]; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95).

Figure 1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Original Pandemic Fatigue Scale (10 Items). Note: PF = Pandemic fatigue.

Figure 2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Modified Version of the Pandemic Fatigue Scale (9 Items). Note: PF = Pandemic fatigue.

Convergent Validity

The scale presented convergent validity (AVE = .59).

Internal Consistency

The PFS presented high internal consistency (CR = .93; α = .93).

Pandemic Fatigue Levels

Participants’ responses to the PFS items ranged from 9 to 45, with a mean score of 29.4 (SD = 8.0), which falls into the category of moderate fatigue. Most of the participants (922; 49.7%) demonstrated moderate pandemic fatigue; 533 (28.7%) high or severe fatigue; and 390 (21%) mild fatigue. Only nine (0.5%) participants presented low pandemic fatigue.

COVID-19-Related Predictors of Pandemic Fatigue

The structural model showed an acceptable fit to the data (SRMR = 0.06; RMSEA = 0.07, p < .001, 90% CI [0.07, 0.07]; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.89). The analysis of structural paths revealed that having had a positive test for COVID-19 (self) did not predict pandemic fatigue (β = .01, p = .789). After removing this non-significant relationship, the model presented a good fit to the data (SRMR = 0.06; RMSEA = 0.07, p < .001, 90% CI [0.07, 0.07]; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90), with the predictor variables explaining 17% of pandemic fatigue variability in this sample. As can be seen in Figure 3, participants who were not teleworking (β = -.06, p = .009) and were in isolation (β = .09, p < .001), who had significant others who tested positive for COVID-19 (β = .09, p < .001), who found teleworking more tiring than face-to-face work (β = .06, p = .004), and considered that pandemic-related news had an individual negative impact (β = .34, p < .001) presented higher levels of pandemic fatigue.

Figure 3 Structural Model of Sociodemographic and COVID-19-Related Predictors of Pandemic Fatigue. Note: PF = Pandemic fatigue.

These relationships varied as a function of age (β = -.06, p = .011), sex (β = -.07, p < .001), and type of confinement (β = .13, p < .001). Younger people, women and participants that answered during full confinement presented higher levels of pandemic fatigue in comparison with older people, men and participants that answered during partial confinement.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to adapt and validate the PFS based on the LFS (Labrague & Ballad, 2020).

In general, our scale revealed good factor and convergent validity, reliability, and sensitivity in this sample, similar to the LFS (Labrague & Ballad, 2020). The PFS presented higher internal consistency than the original scale. Regarding sensitivity and factor validity, Labrague and Ballad (2020) did not provide data that would allow a comparison between the scales.

Item 1 (“I worry a lot about my personal and family’s safety during this pandemic”) had the lowest factor weight, thus, it was removed. This item may be too heterogeneous because it refers to self and others’ safety. Since this scale only assesses pandemic fatigue at an individual level, the reference to others (family) is discrepant from the remaining items and may have confused participants. Moreover, the words “very” and “safety” may have undermined the item’s explanatory power. Since pandemic fatigue can result in a decreased risk perception about getting COVID-19 (WHO, 2020a), people may actually feel less concerned about their personal health, instead of “worrying a lot”. Thus, this item might be reflecting the opposite of pandemic fatigue. The word “safety” might have given rise to different interpretations because it is not clear whether it refers to health and the risk of being infected, or not. Although item 1 was excluded from the analysis because of its mediocre factor weight, we argue that it should be reworded and included in the scale because it provides insights into individuals’ perception of threat from COVID-19. We suggest that the item is rephrased to “I worry about being infected with COVID-19”.

The second aim of this study was to characterize participants’ pandemic fatigue levels and explore COVID-19-related predictor variables.

Almost half of the sample reported moderate levels of pandemic fatigue, followed by high or severe fatigue. Since higher pandemic fatigue levels can negatively affect protective health behaviors and the control of the disease, it is fundamental to develop and implement evidence-based strategies to address this condition. The WHO (2020a) proposes strategies at the governmental level to promote adherence to protective health behaviors. For instance, consistency and transparency in public health communication, and acknowledgment of individuals’ efforts without appealing to fear or blame. Organizations such as the APA (e.g., Clay, 2020), the Order of Portuguese Psychologists (e.g., 2021) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) make individual recommendations, among which is to identify and accept one’s own thoughts and emotions, keeping the body active and a healthy diet, finding new ways to connect with others through digital media, and limiting COVID-related news exposure.

Regarding our structural model, it was found that face-to-face work, being in isolation or quarantine, having friends or family members who tested positive for COVID-19, finding teleworking more tiring, and feeling that pandemic-related news has an individual negative impact were significantly related with higher levels of pandemic fatigue, especially in female and younger participants who responded during the period of full confinement. This finding is congruent with those of Bartoszek et al. (2020), Labrague and Ballad (2020), Lilleholt et al. (2020), Nitschke et al. (2020), and Teng et al. (2020).

On the contrary, having tested positive for COVID-19 did not relate with pandemic fatigue, whereas others’ positive test result did. We argue that this finding may be due to three hypotheses. First, since most of the participants in our sample are relatively young (M = 37.73), it is possible that they have a lower threat perception and are more concerned about a positive test result of their significant others, especially if they belong to a high-risk group (e.g., older people, people with health conditions). Secondly, having family members or friends who have tested positive for COVID-19 may entail increased individual responsibilities by having to take care of those persons or stay away from them, which can lead to pandemic fatigue, as suggested by Sagherian et al. (2020) study. Lastly, when someone gets infected with COVID-19, the situation is under the infected person’s control, which might know what has to be done to control the spread of the virus. In contrast, when it is the other (significant) person who is infected, the situation is beyond the individual’s control, who does not know how that person is feeling, what the prognosis will be, or whether he or she is following the safety rules.

Contrary to the evidence from Contreras et al. (2020), teleworking correlated with lower levels of pandemic fatigue, which means that participants who were in face-to-face work presented higher pandemic fatigue levels in comparison with teleworkers. Empirical evidence suggests that previous experience with teleworking (Nguyen, 2021), the presence of proactive coping skills and future time orientation (Chang et al., 2020), and less resistance to change (Mininni & Manuti, 2020) facilitate the transition from conventional to remote work by enhancing individuals’ adjustment and flexibility. In addition, being younger, having stronger digital skills and conceiving telework as an opportunity to spend more time with family and engage in valued hobbies may also account for the positive relationship between working from home and lower levels of pandemic fatigue (Mininni & Manuti, 2020). Another tentative explanation we postulate has to do with the fact that teleworkers are not faced with the same constant stressful reminders of the pandemic that non-teleworkers are, such as mandatory wearing of face masks, keeping a safe distance from others, or worrying about hand sanitizing after touching surfaces.

However, the results also indicated that participants who found teleworking more tiring than face-to-face work reported higher levels of pandemic fatigue. This can be explained by the fact that these individuals have undergone a profound change in their family and work routines, working longer hours in a row. In general, people were forced to share the same space with other family members, take care of their children and support them in schoolwork, and found it more difficult to enjoy leisure time.

Feeling that news about COVID-19 has an individual negative impact was the variable that showed the highest weight on pandemic fatigue levels in our model. Being sick of hearing or talking about COVID-19, what Lilleholt et al. (2020) called information fatigue, seems to be a core feature of pandemic fatigue. This finding, along with those of Liu and Tong (2020), and Stainback et al. (2020), emphasizes that frequency and intensity of pandemic-related news consumption, as well as the perceived impact of such news, must not be overlooked from the assessment of pandemic fatigue.

This study presents some limitations that should not be overlooked when interpreting the results. Firstly, having a correlational design, it is not possible to establish cause-and-effect relationships between the variables. Secondly, the non-probabilistic nature of the sampling process does not allow the generalization of results to the Portuguese population, and it also led to some biases. For example, the vast majority of participants are female. Further studies should conduct longitudinal studies to assess the evolution of pandemic fatigue levels over time, considering pandemic-related aspects and the restrictive measures in force, as well as adherence to governmental and health experts recommendations. Thirdly, there are other factors that can determine levels of pandemic fatigue that were not explored. Future research could address this study’s limitations by exploring other relevant factors that may account for pandemic fatigue levels, such as attitudes and perceptions about vaccination, the impact of mobility restrictions, medical complications of COVID-19, and the death of significant others from COVID-19 and the associated bereavement, grief and mourning processes. Individual positive factors that counteract pandemic fatigue should also be investigated in future studies, along with developing and testing the efficacy of interventions aimed to mitigate pandemic fatigue.

This research adds to the literature several contributions to a thorough assessment of pandemic fatigue. In addition to cognitive-emotional aspects measured by the PFS, this study suggests that a comprehensive assessment of this phenomenon must include factors inherent to the pandemic context, such as the period of confinement and isolation. A better understanding of pandemic fatigue is indispensable for establishing strategies and interventions to prevent this condition and the associated health risks, and promote mental health in times of COVID-19. The results indicate that age, sex and pandemic-related factors must be taken into account when devising such strategies and public health policies.

Author contributions

Maria Ferreira: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original draft

Joana Rodrigues: Investigation, Writing - Original draft

Filipa Pimenta: Writing - Review and edition

Ivone Patrão: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing - Review and edition