Online dependence can be defined as an excessive and uncontrolled use of certain online applications resulting in interferences with social relationships and in daily life activities, such as school, academic or professional activities. Online dependence triggers withdrawal-like adverse reactions (e.g., anxiety, aggressiveness, anger, etc.), when there is no possibility to access desired online apps (Yellowlees & Marks, 2007).

Several factors appear to be associated with online dependence, but it is unclear to what extent the associations are independent. Thus, the aim of the present study is to explore a model of statistical predictors of online dependence in Portuguese adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Variables expected to be associated with online dependence include food addiction, poor sleep quality, absence of physical activity and negative family interactions.

Food addiction refers to the excessive and uncontrolled consumption of food (usually processed, such as saturated sugars with high calorie content) with addiction-like characteristics (Gearhardt et al., 2011). Preliminary research has shown that food addiction is associated with measures of online dependence, such smartphone addiction (Domoff et al., 2020), social media addiction (Panno et al., 2020), and internet addiction (Martins & Pimenta, 2019; Yildirim et al., 2018). Congruently, research has shown that higher consumption of unhealthy foods correlates with longer exposure to screens (Marsh et al., 2013), and online dependence was associated with obesity in children and adolescents (Bozkurt et al., 2018).

Individuals very dependent of Internet apps may have inadequate sleep duration due to time spent online, although it cannot be excluded that, in certain cases, sleep problems or some associated conditions may lead to online dependence. In the research of Zhang et al. (2017), young people who were diagnosed as online addicts showed poorer sleep quality. Additionally, Salfi et al. (2021) showed that, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescents' increased exposure to screens before bedtime was associated with increases in sleep disorders, including worsening insomnia symptoms, more reduced sleep time, increased time to fall asleep, and difficulties waking up.

Online dependence has also been associated with absence of regular exercise (Hassan et al., 2020) and with less time walking (Alaca, 2020), perhaps due to the time spent online, or because lack of motivation for exercise may favour a preference for sedentary activities, such as online ones. However, there are studies showing no associations between online dependence and lack of physical activity (Dang et al., 2018).

Research also shows associations of greater online dependence with more negative family interactions and fewer positive family interactions; for example, in studies with adolescents, online dependence was found to correlate with less affective engagement in family interactions (Pace et al., 2014), as well as more conflictual and dysfunctional family environments (Wu et al., 2016).

To summarize, the present study seeks to replicate, in a sample of Portuguese adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, the association between greater online dependence and 1) greater food addiction, 2) poorer sleep quality, 3) absence of physical exercise, 4) more negative family interactions, 5) fewer positive family interactions. It is then explored the extent to which online dependence is independently associated with these variables.

Methods

Participants and procedure

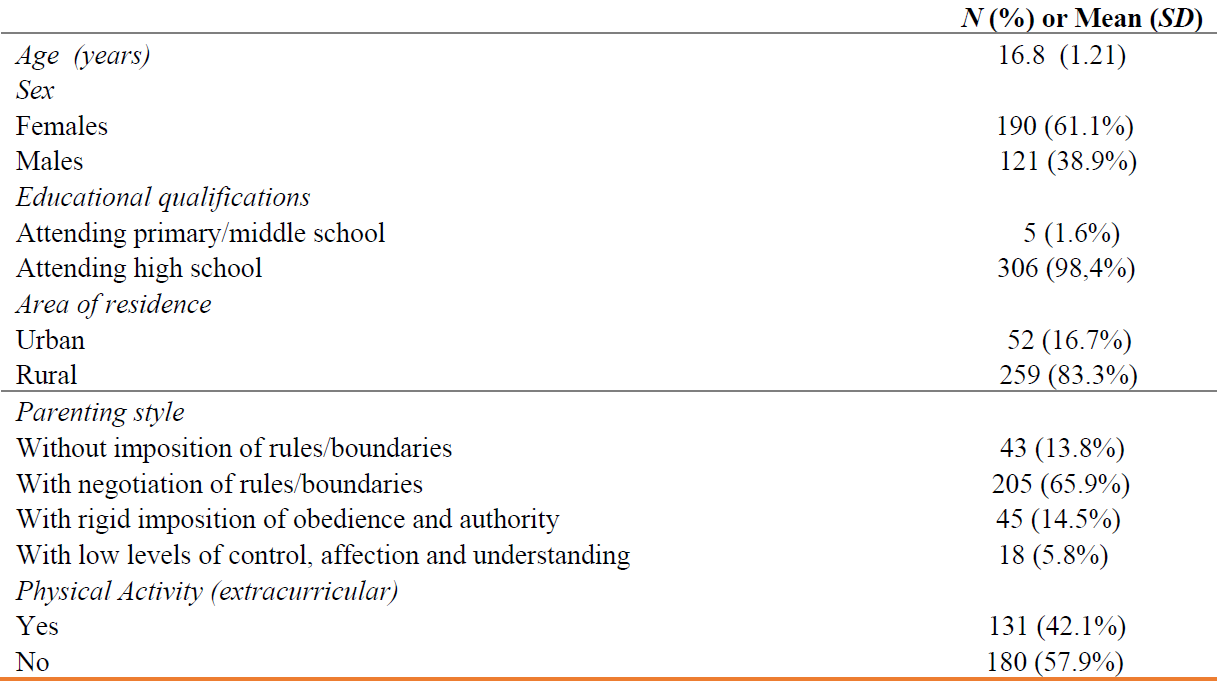

The study sample consisted of 311 participants (61,1% females, 38,9% males). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. Table 2 presents the characteristics of new technology usage. The participants completed an online questionnaire through Google Forms, which was part of the project Geração Cordão. The study received approval of the local Ethics Committee and of the Ministry of Education of Portugal. Researchers contacted a school in the municipality of Torres Vedras, near Lisbon, where teachers passed the survey to their students, after parents of minor students having provided consent.

Measures

Online dependence was measured using the Portuguese version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) (Young, 1998; Pontes et al., 2014). This instrument consists of 20 items with a six-point Likert scale (0-Not applicable; 1-Rarely; 2-Ocasionally; 3-Many times; 4-Frequently; 5-Always). The higher the score obtained, the higher the level of dependence. Normal use ranges between 0-30 points; mild dependence between 31-49 points; moderate between 50-79 points; severe between 80-100 points (Young, 2011).

Food Addiction was measured by the Yale Food Addiction Scale (P-YFAS (Gearhardt et al., 2009; Torres et al., 2017). The questionnaire is composed of 24 items rated on a five-point scale (e.g., "I notice that when I start eating certain foods, I end up eating much more than I had planned").

Sleep quality was assessed by the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) (Bastien et al., 2001). This scale was developed taking into consideration the various diagnostic criteria for insomnia. It is composed of eight items. The first three assess difficulty in falling asleep, waking up often during the night and waking up earlier than expected. The next two items assess the quantity and quality of sleep and the last three assess the feeling of well-being throughout the day, physical and mental functioning during the day, and the level of sleepiness during the daytime period.

Quality of family interactions was measured by the Family Assessment Device (FAD) - General Function (Epstein et al., 1983). This subscale is composed of twelve items. Half of the items assess positive interactions (e.g., "In times of crisis we can count on each other when we need support") and the other half assess negative interactions (e.g., "We can't talk to each other about the sadness we feel"). Responses are obtained through a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("Strongly Disagree") to 4 ("Strongly Agree").

Physical activity was assessed by asking participants if they engaged in regular physical exercise outside school activities, and if yes, how frequently. We used a dichotomous variable expressing lack of physical exercise (= 0) vs. practice of physical exercise (= 1), as well as a continuous variable expressing exercise frequency.

Results

Regarding the levels of online dependence according to the IAT scale (Young, 2011), the largest percentage of the sample can be found in the normal level, but about 40% present some level of clinically significant dependence (see Table 3).

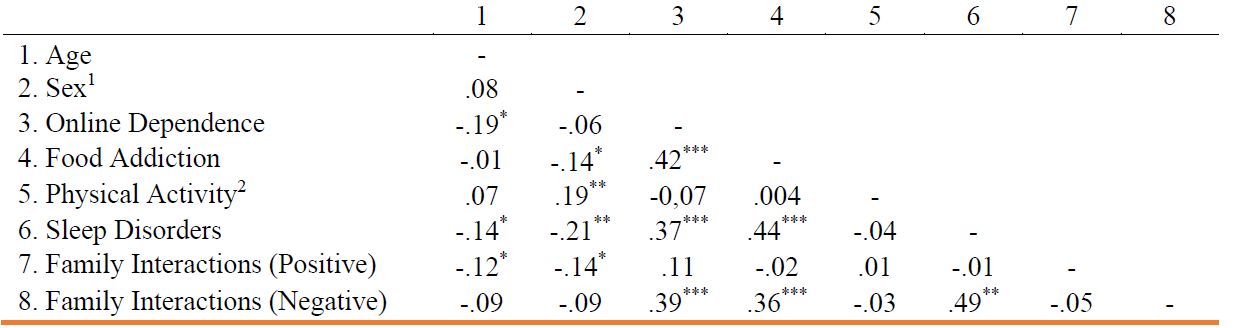

Table 4 presents the intercorrelations between the variables of interest. Greater online dependence correlated with greater food addiction, more sleep disorders, and more negative family interactions, but not with physical activity (dichotomously measured). Additionally, online dependence was uncorrelated with physical activity as continuously measured (r = -.06, p = .279). As seen in Table 4, significant intercorrelations were found between food addiction, sleep problems and negative family interactions.

Table 4 Correlations between the variables under study.

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001; 1Sex: Female = 1; Male = 2; 2Physical Activity: 0 = No; 1 = Yes

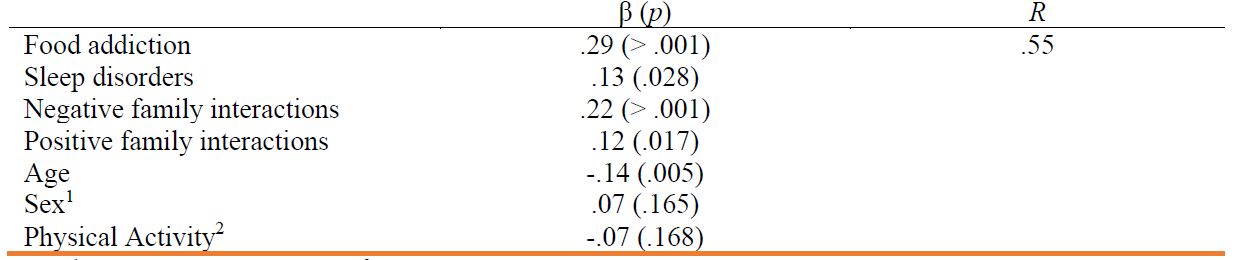

Table 5 shows a multiple regression where online dependence is the dependent variable. The independent variables are age, sex, food addiction, sleep disorders, physical activity (dichotomously measured), positive family interactions and negative family interactions. The results show that online dependence is independently associated with more food addiction, more negative family interactions, more positive family interactions, more sleep disorders, and younger age. Physical activity and sex were not independent predictors. Greater food addiction and more negative family interactions were the strongest predictors of online dependence. Replacing physical activity dichotomously measured by physical activity continuously measured in the independent variables did not change the model meaningfully.

Discussion

We found that greater online dependence correlates independently with greater food addiction, poorer sleep quality, more negative family interactions, younger age, and unexpectedly (albeit weakly) with positive family interactions in a group of Portuguese adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The correlation between online dependence and food addiction is in line with other studies (Domoff et al., 2020; Martins & Pimenta, 2019; Panno et al., 2020; Yildirim et al., 2018), including during the COVID-19 lockdown (Panno et al., 2020). This association might be explained at least partly by deficits in self-regulation (Domoff et al., 2020); that is, individuals with lack of self-regulation attempt to regulate their mood by means of two commonly available activities: eating and using online apps. In fact, many other external regulators (other than substances) might be used for this purpose; these include television viewing, shopping, pornography viewing, gambling (Costa & Brody, 2013; Malat et al., 2010). The need to use these strategies to cope with negative mood likely sustains the behavioural addictions. As research suggests, during the COVID-19 lockdowns, overeating and engagement in online activities increased conjointly as means to cope with lockdown-related dysphoria (Pandya & Lodha, 2021; Panno et al., 2020).

It was also found that greater online dependence correlated with poorer sleep quality and negative family interactions, as expected on the basis of previous studies. However, these variables did not explain entirely the association between online dependence and food addiction.

Lack of physical activity was not a significant predictor of online dependence. Previous studies show that the association between lack of physical activity and online dependence is inconsistent with some studies failing to find such associations (Dang et al., 2018).

In summary, the results show that online dependence is independently associated with food addiction, sleep quality, negative family interactions, and younger age.

Author contributions

Inês Borges: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - Original draft

Ivone Patrão: Supervision, Writing - Review and editing, Project administration, Methodology

Isabel Leal: Supervision, Writing - Review and editing, Methodology

Rui Miguel Costa: Writing - Review and editing, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology