The potentially deleterious effects of stressful events, like cancer diagnosis, can be mitigated by the psychological capacity of human being in adapting to changes, regardless of the gravity or intensity of the adverse situations. While many patients can feel well again and, even, present personal positive change because of their struggle with a traumatic event, others can manifest more difficulties throughout the adjustment process after cancer diagnosis Herschbach et al. (2020). As highlight for Grassi (2020), about 50% of cancer patients can develop psychiatric disorders, including high level of distress and psychosocial conditions, as consequence of cancer diagnosis and its treatment.

One recommended approach to facilitate the early referral of cancer patients in suffering to psychosocial assistance is to implement screening strategies, which can provide information to support interventions and to improve patient and family member experiences during treatment (Bultz, 2016; Donovan et al., 2020; National Comprehensive Cancer Network - NCCN, 2021). Normally, this type of strategy includes evaluation of humor state - mainly levels of anxiety, depression, and distress - and/or the presence of psychological disorders (NCCN, 2021). Using this screening proposal is possible to organize psychosocial assistance to help patients in suffering. However, after this format of screening use, questions came up to us: Is it possible to identify patients with more psychological vulnerability before the level of distress growing up? Can higher levels of psychological suffering due to cancer be prevented or, at least, minimized before the development of more significant psychosocial impairment? The core idea behind the development of this novel instrument was the belief in the plausibility of create a screening tool from pieces of evidence about variables that can predict poor psychological adjustment to cancer.

Psychological adjustment is a multi-dimensional process that involves the interaction of both intra and inter-personal aspects, which vary according to individual attributes, social and environmental context, and characteristics of each phase of the illness. The same individual may react differently depending on the developmental milestone, as well as to cancer type, stage, and necessary treatments (Stanton & Revenson, 2011).

The concept of adjustment adopted to guide the scale development is from the stress adaptation to chronic illness model, coined by Stanton and Revenson (2011). For them, the individual background - named as risk/resilience context - influences how will be the personal cognitive, affective, and behavioral answers to a chronic disease, which, in the end, will impact the level of adjustment achieved on psychological, social, and physical domains. In this model, the risk/resilience context is composed of psychosocial and systemic variables: social/interpersonal conditions (social support and relationship quality); intrapersonal resources (personality attributes and previous behavior repertory); medical circumstances (diagnosis, prognosis, treatment regimen, and its adverse effects); and sociodemographic conditions (socioeconomic level, gender, and cultural influences). Also, after contact with a chronic disease, the responses include affective reactions, cognitive evaluation (primary and secondary evaluations, and the illness perception), and the coping process (approach-avoidance strategies). As a result, the level of adjustment might be observed, for instance, throw quality of life, subjective well-being, and distress evaluations (Hoyt & Stanton, 2012).

According with Hoyt and Stanton (2012), the stress adaptation to chronic illnesses model was based on the transactional model of stress and coping, proposed by Lazarus and Folkman, and its interaction with the self-regulation model, coined by Leventhal. In transactional model, the adjustment process will emerge from the interaction of individual attributes, personal resources, cognitive evaluation, and coping repertory. For them, the cognitive evaluation is the stressor perception (primary evaluation) plus the perception of the self-condition to manage this stressor and related emotions (secondary evaluation). Considering a chronic disease as a stressor, Hoyt and Stanton (2012) introduced in their model the use of the illness perception concept, as proposed by Leventhal, in the place of cognitive evaluation.

The adaptation to chronic illnesses model can incorporate variables frequently pointed as predictors of better or poor adjustment after a chronic disease, that is, variables that can indicate the risk of poor adjustment when facing a stressor. Therefore, we decided to develop and validate a novel psychological screening instrument including a set of predictors of adaptation present in the literature ( illness perception, coping strategies and social support ( and utilizing the present level the distress to represent the adjustment process result, being an indicator of the current level of adaptation (NCCN, 2021). This novel scale, named Psychological Risk Indicator in Oncology (i.e., in Brazilian Portuguese Indicador de Risco Psicológico em Oncologia - IRPO), intends to make it feasible to identify vulnerable patients before the development of higher levels of distress and or psychological disorders throughout the cancer treatment. In summary, the objective of this article is to describe the development and the finding of evidence of the validity of a screening tool to identify cancer patients at risk of poor psychological adjustment.

Method

IRPO Development

To fit the stress adaptation to chronic illness model (Hoyt & Stanton, 2012; Stanton & Revenson, 2011) to the context of oncology, a preliminary revision study was carried out to identify possible predictors of poor psychological adjustment. It was used descriptors, in Portuguese and English, found in the descriptive database DeCS (Portuguese Health Sciences Descriptors), resulting in the following combination of keywords: (ajustamento or adjustment or adaptação or adaptation) AND (psicológica or psychological or psico-oncologia or psycho-oncology) AND (câncer or cancer or neoplasias or neoplasms). This search focused on articles reporting empirical trials, literature review on empirical trials about psychological adjustment and/or adaptation in adult patients with cancer (published from 2002 to 2012). The databases consulted were PubMed, Web of Science, PsycARTICLES, and, in BVS-Psi, PePsic, SciELO and LILACS (Souza, 2014). The primary literature search yielded 3628 articles. Of these, 77 were considered for the purpose of the scale development.

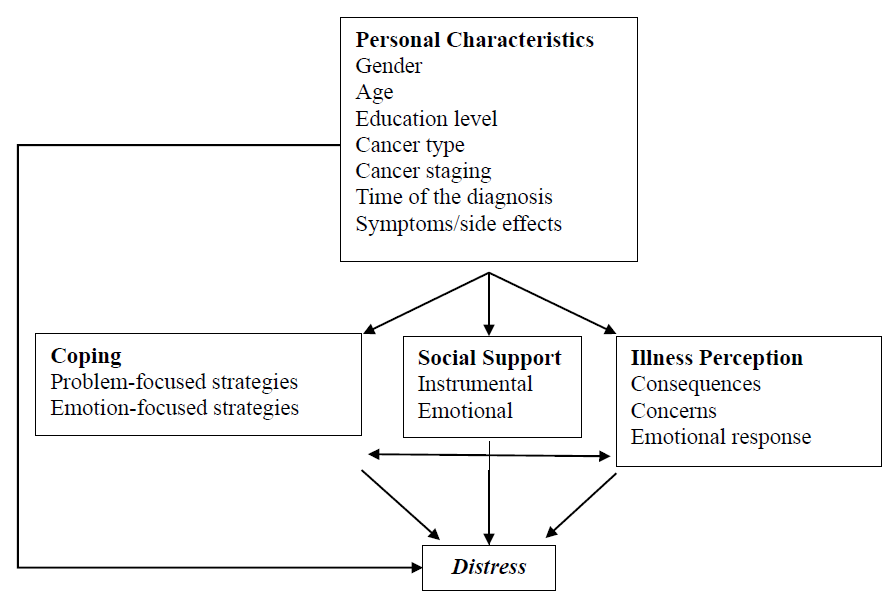

After identified the main predictor's psychological variables, they were grouped into four constructs: coping, social support, negative affectivity/distress, and illness perception. All of them are part of the stress adaptation to chronic illness model. Although medical/clinical and socio-demographic variables were also being mentioned as predictors, characterizing the levels of social and illness' burden, we opted to include only changeable psychosocial variables (Souza, 2014). Then, a theoretical model was developed for the oncology scenery by fitting the four constructs into Stanton and Revenson's model, as presented in Figure 1. In the proposed model, the distress level represents the actual level of adaptation. Coping, social support, and illness perception represent the context of risk/resilience, including a set of individual attributes, behavioral and cognitive reactions during the adjustment process.

Figure 1 Illustration of the psychological adjustment to cancer process based on the theoretic model proposal to the development of IRPO, using distress to represent poor adaptation.

Following Pasquali (2010) recommendations, a mix of validated instruments for measure the predictors previous identified were used as sources of items The item choice considered the list of conditions, perceptions, behaviors, and emotions that had composed each construct. Moreover, items with higher factorial loads (equal or greater than 0.60) were prioritized. It must be highlight that there was no need to maintain total equivalence with the original item. The objective was to adapt the given item to the new instrument, whose content and statistical properties would be validated later. In this regard, the items were adjusted to better fit the cancer diagnosis and treatment context, as well as to facilitate comprehension by patients with lower levels of schooling, a common characteristic among patients attending in Brazilian public hospitals. The constructs used on IRPO development were constitutively defined adopting the theoretical models following described.

Coping was defined by Lazarus e Folkman as a set of cognitive and behavioral efforts/strategies to deal with internal and external requirements to manage the stressor when it is a threat or overcome the individual resources (Dias & Pais-Ribeiro, 2019). To represent the coping strategies with more piece of evidence in the literature, we adapted eight items from Brief-cope Inventory (Carver et al., 1989); three from CSI - Coping Strategy Indicator (Amirkhan, 1990); two from Mini-Mac - Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale (Gandine et al., 2008); and two from DAAS - Diabetes Acceptance and Action Scale (Greco & Hart, 2006).

Social support can be defined as the available assistance patients receive from family, friends, and health team to manage challenging or stressful situations, including the patient satisfaction perception with received support (Cohen et al., 2000). In IRPO development, we prioritized the way instrumental and emotional support functions, an aspect that appears in the literature consulted as having more influence over the adjustment process than merely the number of people available. To represent the social support construct, we selected five items from the scale named MOS - Medical Outcomes Study (Griep et al., 2005), and three from the ESS - Social Support Scale for People living with HIV/AIDS (Seidl & Tróccoli, 2006).

The definition of illness perception adopted comes from Leventhal's self-regulation model. The more the representation of the disease or treatments is perceived as a threat, the greater the perception of stress, affective impact, and the need for coping resources (Hoyt & Stanton, 2012). To compose IRPO's first version, we included four items adapted from the Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ) validated for the Brazilian population by Nogueira et al. (2016).

We adopted the distress definition proposed by the NCCN. For them, distress is a multifactorial, unpleasant experience of a psychologic, social, spiritual, and/or physical nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with a cancer diagnosis, its symptoms and treatments (NCCN, 2021). For composing the IRPO, we adapted 10 items from PSSCAN - Psychosocial Screening Tool for Cancer (Linden et al., 2009).

IRPO Validation Process

The development of IRPO included transversal studies, predominantly quantitative, follow by exploratory factorial analysis and validation process. Study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Humans of the Health Sciences School of the University of Brasília (protocol no 425.266).

Sample

The study population were sampled at the Oncology Center of the Brasilia University Hospital (HUB). The participants were invited, signed the Free and Informed Consent, and answered the interview on the same day of their routine medical visit at the institution through personal contact in the waiting room. Furthermore, before answer IRPO, all of them were asked about the preference between the interviewer applying the instrument or self-administered strategy.

The inclusion criteria include cancer patients both gender, age ranging from 18 to 65 years. The exclusion criteria include refusal participate; medically deaf or hard of hearing; severe or untreated psychopathology; neurologic disorders; dementia; or treat exclusively on palliation.

Pasquali (2010) suggests including at least 5 to 10 participants for each item or at least 200 subjects to carry out the factorial analysis. Considering the first version of the scale included 37 items, it was enrolled 300 patients in Phase 1, however, because of missing data, only 254 ultimately were analyzed.

In Phase 2, it was decided to follow the orientation of Hair et al. (2009) for regression analyses, enrolling 15 to 20 subjects for each independent variable. With five factors in the IRPO final version, it was evaluated 100 patients, but two were excluded due to missing data.

Instruments - Phase 1

Semi-structured interview. Instrument developed to collect socio-demographic and clinical data, including pain.

Version A of the Psychological Risk Indicator in Oncology (IRPO). Preliminary version comprising 37 items divided into 4 domains: illness perception (4 items), social support (8 items), coping (15 items), distress (10 items). The items were assessed with the five-point Likert scale. To determine illness perception, the alternatives were: not at all, slightly, moderately, strongly, excessively. For the remainder of the instrument, the alternatives were: never, rarely, sometimes, often, always.

Instruments - Phase 2

Semi-structured interview. The same Phase 1.

Version B of the Psychological Risk Indicator in Oncology (IRPO). Final version after the exploratory factorial assessment, comprising 27 items divided into 5 factors - negative illness perception (4 items), emotional social support (6 items), instrumental social support (4 items), active coping (5 items), and distress (8 items). In addition to these factors, it is possible to calculate the Overall Psychological Risk Indicator (IGR), where the higher the value, the higher the risk of poor psychological adaptation.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Scale comprised of 14 items measured with four-point Likert scale. In Brazil, it was translated and validated by Botega et al. (1995). Initially used to identify anxiety and depression - seven items in each sub-scale. Currently, its total score is also used to determine levels of distress, with 15 being the cut-off point, with a sensitivity of 0.87 and a specificity of 0.88 (Vodermaier & Millman, 2011).

Procedure

Research assistants were trained regarding assessment procedures: patient recruitment, communication strategy to the interview; how to proceed, if necessary, crisis intervention and/or to refer the participant to psychology service available free of charge at the research center. After the participant signing the informed consent documentation, instruments were applied according with each phase - Phase 1: semi-structured interview and IRPO-Version A; Phase 2: semi-structured interview, IRPO-Version B and HADS. The average time required for interviews, in both phases, was 30 minutes. Afterward, a search for data in medical records was also realized.

In Phase 1, an exploratory factorial analysis was conducted, followed by reliability analysis using the Cronbach alpha (α) coefficient. In Phase 2, the predictive and discriminating validity was evaluated by initially confirming the stability of the factorial structure in a new sample. Afterward, a correlation analysis between the scores of IRPO and HADS was done, followed by multiple linear regression analysis to verify if IRPO scores would predict the total HADS score (distress) and to establish the IRPO general cut-off score.

Results

Table 1 describes the socio-demographic and medical/clinical characteristics of the participants of both phases of the study.

Phase 1

The result of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO=0.880) confirmed the adequacy of the sample with a value considered optimal. No extreme differences were detected between the item’s values, indicating indexes favorable to the factorial analysis in the R matrix. We also detected enough correlations to conduct the analysis (value 4314.673; p<0.001) using Bartlett’s sphericity test. In the correlation’s matrix, no coefficient greater than 0.90 were estimated, and the communalities average (0.64) indicated good common variance between items.

Table 1 Socio-demographic and Clinical Data of the Participants

| Socio-demographic and clinical variables | Phase 1 (N= 300) | Phase 2 (N= 98) | ||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender Female Male | 192 108 | 64,0 36,0 | 74 24 | 75,5 24,5 |

| Marital Status Single Married Divorced Widowed | 78 159 49 14 | 26,0 53,0 16,3 04,7 | 23 57 14 04 | 23,5 58,2 14,3 04,1 |

| Education level Illiterate Incomplete elementary school Elementary school High school Superior education Post-graduate | 34 88 57 91 22 08 | 11,4 29,3 19,0 30,3 07,3 02,7 | 07 40 16 29 03 03 | 07,1 40,8 16,4 29,6 03,1 03,1 |

| Employment Status Active Never work Unemployed Health license Former Receiving benefit | 41 14 55 29 66 95 | 13,7 04,7 18,3 09,7 22,0 31,6 | 04 09 18 11 22 34 | 04,1 09,2 18,4 11,2 22,4 34,7 |

| Time of diagnosis | ||||

| < 1 year | 118 | 40 | 51 | 52 |

| 1 to 2 years | 49 | 16 | 19 | 19 |

| 2 to 5 years | 67 | 23 | 19 | 19 |

| > 5 years | 23 | 07 | 09 | 09 |

| Missing data | 43 | 14 | - | - |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Breast | 96 | 32 | 33 | 33 |

| Gynecological | 42 | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| Head and Neck | 21 | 07 | 10 | 10 |

| Trachea, bronchus and lung | 24 | 08 | 07 | 08 |

| Colon e rectus | 21 | 07 | 08 | 08 |

| Prostate | 15 | 04 | 03 | 03 |

| Gastric | 21 | 07 | 01 | 02 |

| Melanoma | 09 | 03 | 01 | 02 |

| Others | 45 | 18 | 21 | 21 |

| Pain | ||||

| No pain | 154 | 51 | 66 | 68 |

| Mild (1-3) | 71 | 24 | 11 | 11 |

| Moderate (4-6) | 47 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Severe (7-10) | 28 | 10 | 06 | 06 |

The parallel analysis was performed by running Monte-Carlo simulation and the Cattel criterion, retaining five factors, which were extracted by factoring the main components with oblique rotation, oblimin method, and excluding those subjects for whom data were lacking (listwise). Items with factor loading less than ± 0.36 were excluded and items present in more than one factor would remain only in the item with highest factor loading. Afterward, the internal consistency of the five factors was analyzed using Cronbach alpha coefficient ((), verifying the IGR showed good reliability and internal consistency. The instrument ends Phase 1 with 27 items. Table 2 shows the instrument final factorial solution. It is worth not that, due to the IRPO validation was for the Portuguese language, in Table 2 the items are described in Portuguese.

In screening instruments, sensitivity is more important than specificity. The focus is including as much as possible who present the measured mental health condition, even assuming the risk of false-positive. A false positive can be reconsidered after a deeper evaluation at the first appointment, on the other hand, a false negative would drive the patient out of care (Vodermaier & Millmann, 2011).

Based on epidemiologic studies consulted, as around 40% of the population would present some risk of psychological poor adjustment (Holland et al., 2015; NCCN, 2021), the 60th percentile was established as the cut-off point, i.e., the score of 59.

Phase 2

The predictive and discriminating validity of the scale was analyzed, i.e., the degree of correlation with HADS and if the changes in IRPO results reflect data from literature about the influence of certain characteristics of the participants.

Phase 2 participants (N=98) obtained the following HADS scores: anxiety (M=6.82; SD= 3.73; Cv=0.55), depression (M=6.36; SD=4.35; Cv=0.68) and distress (M=13.18; DP= 7.11; Cv=0.54). Between HADS and IRPO scores there were no high levels of collinearity, with absence of correlations greater than 0.90 in the correlations matrix; variance inflation factor (VIF) of each variable less than 05; and tolerance statistic of each variable greater than 0.20.

The correlation analysis between scores from both scales’ domains, socio-demographic and medical/clinical data, reveled similar behavior comparing IRPO against HADS. Furthermore, comparing scores from IRPO in Phase 1 against Phase 2, we verified good stability of the factorial structure and of the internal consistency, as well as the identified correlations was according to the literature regarding the presence of higher psychological vulnerability/risk for female gender, young persons, and single persons (Table 2).

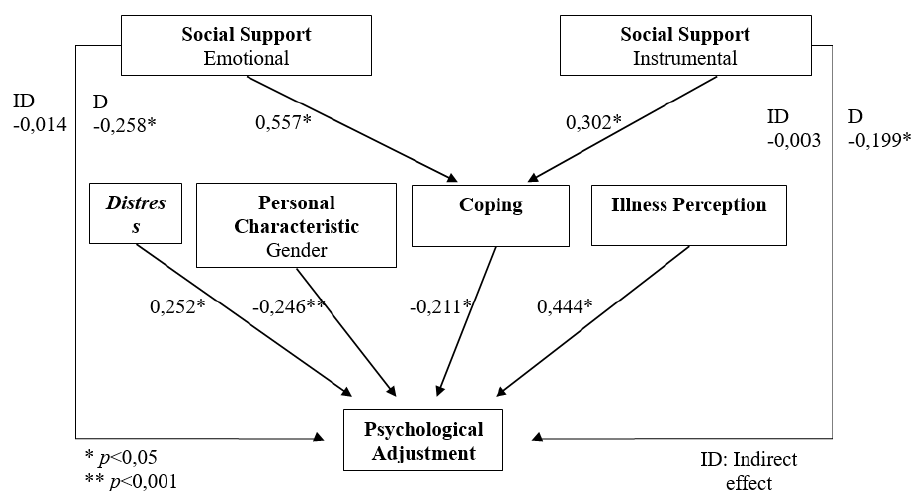

Linear (LR) and standard multiple (SM) regressions was performed to predict how is the effect of IRPO factors on HADS general score (distress level). The regression model comprising IRPO factors - distress, active coping, and negative illness perception - was a good predictor, explaining 59% (R 2 =0.59) of the variation in the total HADS score. In addition, the inclusion of gender in the model increases its explicative capacity (R 2 =0.65). Moreover, a single model developed using only the general score of the IRPO (IGR) was able to predict 47% (R 2 =0.47) of changes in the level of distress assessed by the HADS.

The domains emotional social support and instrumental social support has not directly contributed to predicting the changes in distress level. However, a mediation relation was identified: social support significantly predicted (p<0.001) changing in coping factor scores; coping factor mediated the effect of social support on the distress level.

Finally, after analyzing the residuals from the regression analysis, the adjustment of the model was considered satisfactory, indicating that it could be generalized to other similar cancer patient populations. Once the IRPO predictive validity was tested, the theoretical model developed initially was adjusted to incorporate the new findings (Figure 2).

Table 2 Factorial Solution, Factorial Loads, Communities, and Cronbach's Alphas of IRPO Factors in Adult Patients with Cancer (n= 254)

| Items (In Brazilian Portuguese) | Factor | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | IGR | h² | ||

| Durante a última semana, tenho me sentido nervoso/a e instável. | 0,91 | 0,79 | ||||||

| ... tenho me sentido nervoso/a e trêmulo/a por dentro. | 0,88 | 0,78 | ||||||

| ... tenho me sentido tenso/a e não conseguido relaxar. | 0,85 | 0,74 | ||||||

| ... tenho me sentido agitado/a e achado difícil me acalmar. | 0,84 | 0,72 | ||||||

| ... tenho perdido o interesse por coisas com as quais eu usualmente me importava ou apreciava. | 0,63 | 0,64 | ||||||

| ... meus pensamentos estão repetitivos e cheios de coisas assustadoras. | 0,63 | 0,62 | ||||||

| ... tenho sentido que não posso controlar nada. | 0,62 | 0,67 | ||||||

| No último ano, por duas semanas ou mais, eu me senti triste, desanimado/a ou deprimido/a. | 0,37 | 0,62 | ||||||

| Posso contar com alguém para compartilhar minhas preocupações e medos. | 0,69 | 0,78 | ||||||

| Procuro apoio emocional de alguém (família, amigos). | 0,68 | 0,65 | ||||||

| Posso contar com alguém com quem possa desabafar ou conversar sobre assuntos relacionados à minha enfermidade. | 0,66 | 0,76 | ||||||

| Posso contar com alguém que me ajude a melhorar meu humor, meu astral. | 0,61 | 0,69 | ||||||

| Conto meus medos e preocupações sobre a doença a um amigo ou parente. | 0,56 | 0,56 | ||||||

| Posso contar com alguém com quem fazer coisas agradáveis. | 0,51 | 0,70 | ||||||

| Procuro algo positivo em tudo que está acontecendo. | 0,56 | 0,61 | ||||||

| Tento encontrar estratégias (meios, planos, recursos) que me ajudem a lidar com a doença. | 0,52 | 0,48 | ||||||

| Faço coisas que são importantes para mim, apesar de estar doente. | 0,51 | 0,58 | ||||||

| Sinto que nada do que faço poderá me ajudar. | -0,47 | 0,57 | ||||||

| Tento aprender a conviver com a doença. | 0,38 | 0,56 | ||||||

| Posso contar com alguém que me ajude, se precisar ficar de cama. | -0,86 | 0,82 | ||||||

| ...para me levar ao médico. | -0,83 | 0,74 | ||||||

| ...que me ajude nas tarefas diárias se ficar adoentado(a) /debilitado(a). | -0,82 | 0,77 | ||||||

| Me sinto satisfeito(a) em relação ao tipo de apoio recebido. | -0,65 | 0,74 | ||||||

| Quanto você está preocupado(a) com sua doença? | 0,74 | 0,71 | ||||||

| Quanto a doença afeta a sua vida? | 0,65 | 0,71 | ||||||

| Quanto a doença o(a) afeta emocionalmente? (Por exemplo, faz você sentir raiva, medo, ficar chateado ou depressivo). | 0,55 | 0,65 | ||||||

| Penso que a vida é ruim porque estou doente. | 0,41 | 0,56 | ||||||

| Number of Items | 08 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 04 | 7 | ||

| Eigenvalues | 9,16 | 4,25 | 2,11 | 1,79 | 1,68 | |||

| Explained Variance (%) | 24,91 | 10,94 | 4,52 | 3,77 | 3,37 | 47,52 | ||

| ( | 0,90 | 0,83 | 0,71 | 0,90 | 0,77 | 0,90 | ||

| Mean | 19,0 | 23,9 | 20,9 | 17,8 | 10,5 | 57,8 | ||

| Standard Deviation | 9,1 | 5,7 | 4,3 | 3,6 | 4,0 | 18,8 | ||

| Coefficient of Variance | 0,5 | 0,2 | 0,2 | 0,2 | 0,4 | 0,3 | ||

Note. Factor 1 - Distress; Factor 2 - Emotional Support; Factor 3 - Coping Strategies; Factor 4 - Instrumental Support; Factor 5 - Negative illness perception; IGR - General Risk Indicator

Figure 2 Illustration of the IRPO theoretic model based on the pattern of causation identified in multiple regression carried out in Phase 2, including the Beta values.

As in Phase 1, the 60th percentile was used to determine the score 55 as the cut-off point. This choice was corroborated by the presence of 35.7% of patients with high levels of distress (score greater or equal to 15 in HADS general score). Also, this value was quite like the cut-off based on the regression line, score 56. However, to guarantee sensibility for this screening instrument, the score of 55 was chosen (Vodermaier & Millman, 2011).

In addition, the IRPO proved to be stable for use with individuals at different stages of treatment, highlighting that patient receiving exclusive palliative care were not included in the sample. Regarding the discriminate validity, no significant differences were detected, for both scales - HADS or IRPO - regarding the average scores of the following variables: age, level of schooling, employment status, time since diagnosis, previous oncological treatment, ongoing oncological treatment, and the presence of co-morbidities.

Orientations and Norms for the Use of the IRPO

The scale was validity to evaluate adult patients with any type of cancer, who were not receiving exclusive palliative care. To identify vulnerable individuals before developing high levels of psychological suffering, the screening process using IRPO should be as early as possible, prioritizing the period immediately after diagnosis.

To facilitate correction, the scores for each item were reorganized, and the answers were recoded. The score in each domain is equal to the sum of each domain items, and the IGR is equal to the sum of all items. The higher the score, the higher the level of risk in each domain and in the IGR. An IGR score equal to or greater than 55 indicates the patient should be referred to individual psychological attendance for further and deeper evaluation and, if the risk was confirmed, psychological care should be initiated.

Discussion

The IRPO development considered adjustment as a dynamic and complex process. For this reason, using multiples scales to evaluate a group of specific symptoms - anxiety, depression, distress - may not be sufficient to identify vulnerable patients before clinically relevant psychosocial conditions developing. Moreover, using a mix of scales can overload the screening process. The development of the IRPO sought to consider guidelines regarding how to adequately represent the construct to be evaluated (Pasquali, 2010). The list of predictors extracted from empirical studies regarding cancer patient’s adaptation process allowed a more precise selection of items to compose the IRPO.

At Phase 1 and 2, as expected for a public hospital, in the sample there was a predominance of patients with lower levels of schooling, as well as the most was retired or receiving illness benefits. The average time since diagnosis was equal to 25 months, and most participants had undergone some type of therapy. Both samples were quite diversified, and its profile reflected the cancer estimates for the Federal District for 2018 (Brazil, 2017), except for the low incidence of prostate cancer. For this type of cancer, the surgery is the first and the main treatment and the study was conducted at a clinical oncology center, which explain the smaller number. The characteristics described allowed us to infer that IRPO was tested on a sample that satisfactorily represented the cancer population assisted at the Federal District public hospitals.

The strategy to apply the IRPO was well accepted, even among those who reported pain during the interview. The research assistants perceived patient’s preference by interviewer applying the instrument than self-administers strategy. This characteristic might indicate some acceptability and willingness of cancer patients submit to short psychological assessments, even when applied in common spaces, such as waiting rooms.

It is necessary to indicate limitations of the study: the levels of specificity and sensibility of the IRPO was not determined due to institutional problems that hampered the re-application of the scales over time on a single patient, in a longitudinal approach. However, it was possible to identify evidence of the validity of the IRPO, to test the model upon which it was based, and to determine the cut-off point. In subsequent studies, re-assessment of the same patient at different moments of the illness would allow expanding our knowledge of the IRPO predictive capacity, and to establish specificity and sensibility levels. Since the variable gender increased the explicative capacity of the model upon which the instrument was developed, in future studies it would be relevant to verify effectiveness regarding the development of different cut-off scores when assessing men and women.

It must be highlighted that the screening process per se is not the answer to overcome difficulties faced by patients: it only the first step to developing the health team course of action. The results will depend on the capacity of the psychology team to absorb the evaluated patients, the training of these professionals, and collaboration with the other health professionals (Holland et al., 2015). Furthermore, the moment the IRPO is applied must not be unique and rigid. The identification of patients at risk of poor adjustment might take place at any time during treatment. However, priority must be given to assessments made as early as possible.

From a clinical perspective, the IRPO domains scores may also be used to conduct assessments and interventions throughout the psychotherapeutic process, providing a multifaceted framework to better understand patients’ support needs. In this regard, further studies could test the IRPO as a framework to the development of interventions tailored to its different domains, as well as to evaluate the efficacy of interventions, and its capacity to measure the patient progress during the various stages of treatment.

Considering that another scale to compare with the IRPO is not to our knowledge, we concluded that the IRPO might be a useful psychological screening instrument based on its validity evidence. The various techniques used demonstrated the viability of its use according to recommended theoretic and psychometric parameters. Beyond identifying cancer patients in suffering, recognizing who are at risk of poor psychological adjustment, psycho-oncologists can design preventive interventions and take a more active and less reactive role in psychosocial cancer care.

Contribuição dos autores

Juciléia Souza: Concetualização; Curadoria dos dados; Análise formal; Investigação; Metodologia; Administração do projeto; Supervisão; Validação; Visualização; Redação do rascunho original; Redação - revisão e edição.

Eliane Seidl: Concetualização; Redação do rascunho original; Redação - revisão e edição.

Daniel Barbosa: