Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Cadernos de Estudos Africanos

versão impressa ISSN 1645-3794

Cadernos de Estudos Africanos no.29 Lisboa jun. 2015

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Migration, Remittances and Development: A case study of Senegalese labour migrants on the island Boa Vista, Cape Verde

Migração, remessas e desenvolvimento: Um estudo de caso de trabalhadores migrantes senegaleses na ilha de Boa Vista, Cabo Verde

Philipp Jung*

*Centro de Estudos Internacionais (CEI-IUL), Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026, Lisboa, Portugal, philippromanjung@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Cape Verde has become increasingly a destination for international migrants from continental West Africa. The aim of this paper is to explore migration of Senegalese to the Cape Verdean island of Boa Vista with a focus on migration decisions and remittances and attempts to link it with the broader migration and development debate. It starts with a review of the literature on empirical findings and theoretical approaches examining migration as a method of risk minimization and links between migration and development. In the second part these approaches are reviewed in the light of empirical evidence about migration processes and flows of remittance between Senegal and Cape Verde. The importance of Cape Verde as a destination for international migrants from West Africa has increased considerably since the millennium. This article present data examining the motives for emigration and immigration and the characteristics of the remittances sent by migrants.

Keywords: migration, remittances, food security, Senegal, Cape Verde

RESUMO

O objetivo deste artigo é explorar a relação entre migração e segurança alimentar, e migração e desenvolvimento, num sentido amplo. Assim, o artigo inicia-se com uma revisão da literatura sobre resultados empíricos e abordagens teóricas, que examinam a migração como um método de minimização de riscos e da relação entre migração e desenvolvimento. Na segunda parte, essas abordagens são revistas à luz da evidência empírica sobre os processos de migração e fluxos de remessas entre o Senegal e Cabo Verde. Desde o início do novo milénio, Cabo Verde tornou-se cada vez mais um destino de migrantes internacionais da África Ocidental continental. O artigo apresenta dados que examinam ambos os motivos para a emigração e imigração e as características das remessas enviadas para casa pelos migrantes.

Palavras-chave: migração, remessas, segurança alimentar, Senegal, Cabo Verde

Since the end of the 20th century, Cape Verde has become increasingly a destination for migrants from member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Senegal has taken a central place in this West African migration system. Besides Cape Verde international migration from Senegal is directed to a variety of other regions and countries (Tall, 2008a; Flahaux, Beauchemin, & Schoumaker, 2010). According to the World Bank about 632.000 Senegalese live abroad, an estimated 4.9% of the total population[1] (The World Bank, 2011, p. 217). It is estimated that at least 70% of all Senegalese households have one or more family members who migrated internally and/or internationally (Land & Fourier, 2012, p. 42) and remittances are for many of them an important income source. According to the World Bank remittances to Senegal have more than doubled between 2003 and 2010 from 511 million US$ to over 1.1 billion US$ (The World Bank, 2011, p. 217). It is estimated that in 2011 remittances counted for about 10.3% of Senegals gross domestic product (GDP) (ANSD, 2013, p. 57). Most literature on the subject deal with international migration to either Europe or North America (Mezger & Beauchemin, 2010; Riccio, 2008; Tall, 2008a, 2008b), less is known about intra-regional flows of migration and remittances, despite its (equal) importance (Land & Fourier, 2012, p. 41; ANSD, 2013, p. 47; Lessault & Mezger, 2010). Intra-regional migration is common and also not a recent phenomenon in West Africa; examples are the labour migration to the plantation economies of Ghana and Côte dIvoire beginning in the 1950s, or to Nigeria during the years of the oil boom in the 1970s (Adepoju, 2004, 2006; Ramamurthy, 2003). This paper analyses the migration of Senegalese to the Cape Verdean island Boa Vista with a focus on migration decisions and remittances and attempts to link it with the broader migration and development debate. Hereby it adds both knowledge about remittances in the environment of intra-regional migration in West Africa and more specific about the relative new and until now barely researched phenomenon of immigration to Cape Verde.

Migration, remittances and development: a review of literature

Today about 200 million people, 3% of the worlds population, live outside their country of birth. Remittances sent home by these international migrants are seen increasingly as a means for economic development and poverty reduction in developing countries (Zezza, Carletto, Davis, & Winters, 2011, p. 1). Since the 1990s remittances increased rapidly. Officially recorded remittances to developing countries have reached $351 billion in 2011 and constitute more than 10% of the GDP in many developing countries (Mohapatra, Ratha, & Silwal, 2011, p. 1; The World Bank, 2011). The actual figure is estimated to be higher, since a big part of the money is transmitted through private or informal channels. As a consequence of this rise there has been an increased interest, both scientific and political, in international migration and remittances or as Faist (2011) calls it, enthusiasm for international migration as a central mechanism to advance what is called the development potential of international migrants (p. 5). Despite this growing attention, the impact of migration on development is neither a recent phenomenon nor a new discovery. It has been discussed in the migration debate in its various facets since the 1950s, with changing focus on positive or negative aspects. These viewpoints are reflected in the different theories to explain migration (Portes, 2007; De Haas, 2007). Although there are many ways in which migration can have an influence on development, be it positive or negative, the focus of the so called migration development nexus is mostly on remittances and their economic consequences[2]. This paper analyses the impact of remittances on the micro level of households. This focus should not mean that migration to Boa Vista does not have other effects on development besides the ones through remittances.

It is often assumed that remittances contribute to poverty reduction and income diversification. Theories like the new economic of labour migration (NELM)[3] (Stark & Bloom, 1985; Stark & Taylor, 1989; Massey et al., 1998) or sustainable livelihood approaches[4] (McDowell & De Haan, 1997; De Haan, 1999; Bebbington, 1999) suggest that migration is part of household strategies to diversify income sources. Hereby it is rather a means to minimize risks through the diversification than to maximize income. The disposition to risk minimization behaviour instead of individual income maximization results according to moral economy approach[5] from two aspects. First, the well-being of the household outweighs the individual one. Secondly the behaviour of households in risky environments tend to be rather risk-averse than risk prone (Hyden, 2001, p. 10021).

Households can control risks, like food insecurity, unemployment or poverty in old age better than individuals by diversifying the distribution of income resources at their disposal. In the absence or unavailability of governmental programs or private insurances the affiliation to a household can diminish the vulnerability to risks. Households have developed a variety of livelihood strategies to cope with risks and precarious conditions in general. The migration of one or more household members to places with better income opportunities is a central part of these livelihood strategies.

A variety of studies show how remittances help both rural and urban households to address and reduce the impact of unanticipated economic shocks such as crop failure or a rise in food prices, to optimise livelihood security and reduce poverty (Adams & Page, 2005; Hampshire, 2002; Latapí, 2012; Quartey, 2006). Lindley (2006) or Lacroix (2011) describe different ways in which remittances have impacts on the micro level, mostly by covering regular basic expenses, above all regarding alimentation, but also as coping mechanism in situation of risks. After food expenditures, remittances are mostly used for education and health of children. This investment in human capital is likely to be important for the long-term development prospects of a country.

According to NELM migration is not only a strategy to minimize risks, but also to gain access to investment capital and consumer credit. In developing countries the lack of efficient banking systems and difficulties to qualify for credits hinder households to make investments, for example in the increase of agricultural productivity, human capital, improvement of housing situations or simply in consumer goods (Massey et al., 1998, pp. 24-26). Critics, however, argue that remittances are mostly used for consumption and non-productive activities and hereby rather create new forms of dependencies, than lead to sustainable development (ibid, p. 254). Furthermore it has been criticized that migrants prefer to invest in urban economies and here mostly in the trade and service sector rather than in production with stronger links to raw materials or in agriculture (Smith, 2007, p. 124). Although this scepticism on migration and its effects on development need to be considered, it is criticized for its empirical weakness (Massey et al., 1998, p. 254; De Haas, 2007, p. 14). Several studies suggest that remittances receiving households have a higher propensity to invest than non-migrant households (Rapoport & Docquier, 2005, pp. 70-74; Massey et al., 1998, pp. 260-261). It is also generally not easy to distinguish between the different sources of household income for specific expenditures (De Haas, 2007, p. 14). Remittances which are used for consumption may have the side effect to free other income sources for investment. The usage of remittances also seems to change over time. While in the beginning remittances are mostly used for the payment of basic needs, investments occur in most cases later. It often takes time until remittances begin to flow, since migrants need time to establish themselves in the new environment and find relatively secure employment (De Haas, 2007, p. 15; Lindley, 2006, p. 16). Investments also depend on more general investment conditions. Often the same conditions which promote migration generally discourage investment. Migration and remittances alone cannot remove these structural constraints to economic growth (Massey et al., 1998, p. 255; Faist, 2011, p. 11). The lack of infrastructure, access to markets and agricultural resources, may lead migrants to invest in other places, mainly in urban or semi-urban centres (De Haas, 2006, pp. 574-576).

The building, improvement or maintaining of a house is the most common form of investment (Lacroix, 2011; De Haas, 2006; Smith, 2007, p. 94). Migrants are often criticized for this unproductive use of remittances, which often is a response to uncertain, inflationary environments, in which investment in economic activities is characterized by high risks and costs. Investment in housing or land on the contrary is relatively safe and also offers future income sources. Furthermore better housing can lead to an improvement of the health situation and the well-being of the household. In general by considering only economic activities as investment one may also miss out other important aspects of development. Expenditures in education, health or food and investment in housing can improve the well-being of households and enable them to live the lives they have reason to value (De Haas, 2007, p. 17).

Remittances are sent out of a desire to help the family, but also out of feelings of obligation. The assumption that moral norms and beliefs structure economic activities is elementary for the concept of moral economies. McDowell (2009) describes moral economy approaches as either the study of ethical beliefs and normative assumptions that structure economic actions or a subset of economics in which a particular view of morality is the underlying principle of exchange (pp. 186-187). Moral assumption in connection with remittances can be for example the expectation that a good son or daughter supports the parents by sending money or that the money is used for alimentation or education and not for pleasure and material things which are not essential for the livelihood.

Senegalese labour migration & remittances on the Cape Verdean island Boa Vista

Methodology

The suggestions presented above regarding migration to Cape Verde have hardly been examined. The following qualitative case study aims at a better understanding of intra-regional migration and remittances in West Africa and attempts to link the empirical reality of the migration from Senegal to the Cape Verdean island Boa Vista with the broader debate on migration and development[6]. It analyses both migration decision-making processes and flow of remittances. Using a triangulation of research methods empirical data was collected both in the country of origin and at the destination in order to comprehend circumstances at both ends of the migration flow[7]. In Cape Verde a questionnaire survey was completed with 68 Senegalese migrants[8] and problem-centred interviews with seventeen male migrants were carried out. In Senegal 12 problem-centred interviews with relatives of immigrants, nine in Dakar and three in Diourbel, and one with a Senegalese currently living in Diourbel, who was deported from Cape Verde in 2009, were conducted. Unrecorded conversations and observations complemented the gathered information.

At this point it needs to be mentioned that statements about remittances made by migrants and their relatives do not necessarily refer to actual value and frequency of the economic transaction, but also represent moral assumptions as described above. Different methodical aspects, including the situation in which interviews and questionnaire were conducted, alone or in the presence of other persons, and dynamics between interviewee and researcher, need to be considered. The survey often took place in the presence of other persons. In some cases statements about remittances may be embellished in front of others in order to improve the reputation. At the same time complains from migrants about difficulties in Cape Verde and pressure to send money or from relatives about insufficient or declining remittances may be exaggerated in the presence of the author.

Although answers in both questionnaire and interview may not be always accurate, they allow the identification of patterns, not only in relation with moral assumptions, but also about the actual flow and usage of remittances. The triangulation of research methods and the conducting of empirical data at both ends of the migration systems allow the control and comparison of the obtained data. Thus answers from migrants and their relatives could be compared and statements about value and frequency of remittances could be verified. Furthermore observations confirmed findings from questionnaire and interviews and allowed conclusions about the actual flow of remittances.

Migration to Cape Verde

Cape Verde is widely known for emigration and not for immigration. Although it is difficult to ascertain the exact number of the Cape Verdean diaspora, it is estimated that people with Cape Verdean origins outnumber the total population of the archipelago of roughly 500.000 (Carling & Batalha, 2008, pp. 19-20). A steady economic growth over the last two decades[9] and an extension of the tourism sector[10] resulted in a growing demand for cheap but also qualified labour, especially in the construction sector. As a consequence the archipelago became attractive as destination for migrants from other ECOWAS member states[11], mainly from Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Nigeria since the beginning of the new millennium[12]. This leads to the question why the islands, 500 km west off continental Africa are chosen as a destination, while at the same time Cape Verdeans continue to seek their luck outside their home country. In this context it is important to include social and cultural factors in the analysis of migration decisions. [T]he aspirations to migrate are not simply motivated by material desires. [ ] Desires to migrate are shaped in (trans)local processes that concern peoples ideas about the good and right life (Åkesson, 2008, p. 269).The perception of migration as an important event in the life story is widespread in both Cape Verde (Åkesson, 2008; Carling & Åkesson, 2009) and Senegal (Riccio, 2005). An explanation of migration based solely on economic factors without considering the variety of social and cultural aspects which influence migration decisions is therefore not useful. Finally emigration and immigration in the Cape Verdean context cannot be easily connected. The country is part of different migration systems, both as destination and as country of origin. Aspects which attract Senegalese may not necessarily be an argument for Cape Verdeans to stay in their country.

Main destinations for international migrants in Cape Verde are the two touristic islands Sal and Boa Vista, the archipelagos main island Santiago and São Vicente with the port city Mindelo. Boa Vista is besides Sal the island with the highest number of tourist accommodations[13]. The extension of the tourism sector with the construction of hotel complexes and an international airport created demand for labour and attracted both migrants from other Cape Verdean islands, mainly from Santiago, and from mainland Africa. The number of employees, who work officially in tourism, increased from 110 in 1999 to 1.776 in 2011 (INE, 2014b). The actual number of people, who earn their living with tourism is higher, since the official data excludes work in the informal sector, for example artists who produce souvenirs and street sellers, both areas in which especially Senegalese operate.

According to the INE 1.364 Senegalese[14] count for 11% of the total foreign population in Cape Verde (INE, 2011). The Global Migrant Origin Database from the Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty (Migration DRC), which uses data from the RGPH 2000, records 206 immigrants from Senegal (DRC, 2007). This would suggest that the number of Senegalese in Cape Verde increased about eight times between 2000 and 2010. In the case of Boa Vista, the 2010 census registered 125 Senegalese living on the island, but also here the actual number is probably much higher. The association of Senegalese migrants, Association des Sénégalais de Boa Vista has about 180 members. This number also only allows a rough approximation, since not all migrants are members and those who are, are not necessarily remaining on the island any longer. Conversations with Senegalese migrants lead to an estimation that the actual figure lies between 200 and 250.

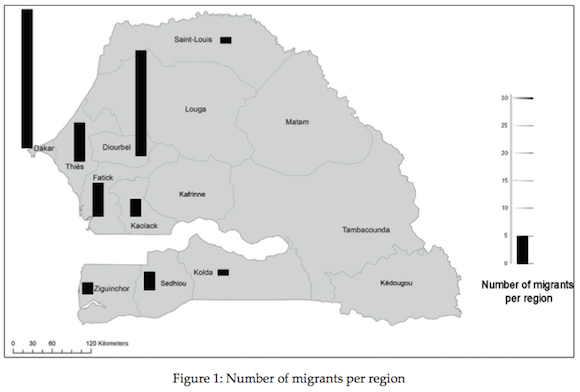

Figure 1 shows the region of origin in Senegal and respectively the number of migrants as a result of the questionnaire survey. Senegalese from nine of the fourteen administrative regions reside in Sal Rei, but they are not evenly spread. Out of the sixty-eight questioned Senegalese, about 65% were born either in Dakar or Diourbel. The two are also main regions for emigration from Senegal in general (ANSD, 2013a, pp. 47-48). The largest part of the migrants is either younger than 30 (49%) or under 40 (41%). The average age is 31 years. This confirms suggestions found in the literature that mostly young men under 35 years emigrate from Senegal (Land & Fourier, 2012, p. 42). However, in the case under study, they are not, as often suggested, mostly unmarried. Married and unmarried migrants are almost equally distributed in the survey, the former count for 51.5% of the surveyed persons.

The case of Ibrahim[15], a 26 year old migrant from Dakar, who arrived in Cape Verde in 2007 and after a short-period in Sal moved to Boa Vista exemplifies the situation of Senegalese on the island and their interaction with their relatives at home. Ibrahim decided to chercher la vie, words used by many migrants, outside of Senegal and hereby also be able to help his parents. He works as an artist, the same profession he practiced in Dakar, and sells his paintings to different souvenir-shops in Sal Rei. He accepts to live in poor living conditions in order to save money and be able to send some home. He rents a room for about 100 EUR per month from a Guinea-Bissauan in Barraca, an informal settlement that is built on former salt evaporation ponds just outside of the town. High prices for water and electricity are a further burden for his income. Besides the high costs of living, the insecurity of his work presents his biggest problem, while racism and xenophobia[16], which were mentioned by many migrants, rarely seemed to have affected his life in Boa Vista.

Ibrahim stated that he remits once a month, in good times between 250 and 300 EUR, in bad times less than 100 EUR. According to his brother, who lives with the family in the region of Dakar, Ibrahim only sends every two to three months 100 to 150 EUR. Ibrahims statement may reflect more the moral assumption that he should support his family through regular monthly transfers than through the real, rather sporadic, remittances. Although according to him his family understands his situation in Boa Vista, they complain if he does not send anything at all. Expectations of his family make it almost obligatory for him to send money frequently, but he also stated that it is important for him to support his family. Remittances and regular conversations via internet or telephone connect Ibrahim and his family at home. Furthermore he returns every two years to Senegal to see his family and by this reinforces the ties between them. The situation of Ibrahim is similar to many migrants in Sal Rei and his motives for the migration are comparable with the ones of other migrants, as the following analysis of motives for the emigration and choice of destination shows.

Migration motives

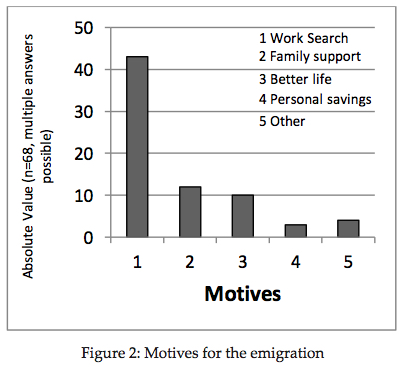

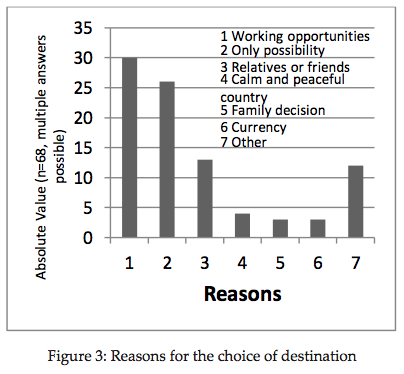

Both the motives for the departure from Senegal (Figure 2) and the choice of Cape Verde as destination (Figure 3) are presented here, as a result of the questionnaire survey. The responses are summarised in categories. Additionally, extracts of problem-centred interviews are used to analyse and illustrate individual differences in decision-making processes.

As motive for the emigration the great majority (63%) stated that they left Senegal for economic reasons. It is not surprising that migrants perceive the absence of employment opportunities and problems to earn money in a country, which is characterized by a lack of employment in the formal sector (Diop, 2008; Gerdes, 2007) and a high population growth (Land & Fourier, 2012, p. 39) as pressure and main reason to emigrate. Another important reason is the desire or obligation to support the family (18%). The category In search of a better life (14%) is often, but not solely connected with economic conditions. The improvement of the living conditions can be understood as satisfaction of basic needs as well as the acquisition of consumer goods. Both are difficult to satisfy due to lack of revenues, but also as a result of obligations. The desire to escape these obligations and gain some financial independence and ability to economise money was mentioned by 4% of the survey participants.

Le Sénégal, jai quitté là-bas, parce que jétais au travail chaque jour, je nai jamais resté sans travail. Mais avec ta famille, tu peux pas garder largent, parce que à chaque fois la famille a besoin de quelque chose, tu dois les soutenir de cela. Cest pour cela que tu ne peux pas réaliser rien de ta vie.

The statement above was made by a Dakarois, who perceived it as pressure that all the money he earned remained with the family, while he was not able to safe or spend it in a preferred way. Despite his desire to gain some money for himself, he continues to support his mother and siblings, who live in Dakar, whenever possible. This case shows that the desire to support the family and the wish to economise money for oneself do not necessarily exclude each other. Although not often stated by the surveyed migrants, the aspect of economic independence may be more important as the results suggest. In order to conform to moral assumptions migrants may prefer to present themselves rather as supporter of the family than as a person who searches for his own profit. Motives and behaviours which could be perceived as selfish and improper may not be mentioned in the open, but this does neither mean that they do not influence the decision to migrate nor that they are not relevant for the questioned migrants. Distance can also signify the loss of control over the migrant by his parents and not only regarding the above mentioned economic aspect. This aspect, especially with regards to alcohol, was only mentioned during informal conversations.

A variety of aspects also influence the decision for choosing Cape Verde as destination. Answers related to employment opportunities are still the most stated (44%), but in comparison to job search as a motive to leave Senegal they become less important. The image of a better job supply in Cape Verde is not always met as the following statement by a migrant indicates. I thought that there is work here. My older brother told me that it is good here. But these times already passed. Many migrants expressed their disappointment about the situation in Boa Vista and difficulties to find work. Diop (2008, pp. 25-26) speaks about an économie symbolique or a géographie mentale of migrants, which do not necessarily match real economic conditions, but can influence strongly the decision to migrate. The image of better opportunities outside of Senegal is widespread, especially among the youth. A Senegalese, who was unemployed at the time of the fieldwork, stated that it is this imagination, which prompted not only him to emigrate, but animates Senegalese in general to leave their country.

Souvent tu penses là où que tu vas, peut-être cest là-bas, que tu vas être mieux, plus doù que tu as quitté. Cest ça que nous anime. Cest comme ça. Là-bas [Sénégal] aussi tout le travail va bien.

Of similar importance for the decision to migrate to Cape Verde is the political dimension. Cape Verde as a member of ECOWAS does not restrict the entry of citizens from other member states with visa regulations[17]. Furthermore the financial burden also plays an important role. It is cheaper to migrate to Cape Verde than to Europe. The answers summarized under the category Only Possibility (38%) are related to these aspects and the following quote from a problem-centred interview with a migrant from Diourbel exemplify them.

Non, ici cest facile pour les gens sénégalaises venir ici, parce quil ny a pas le visa, il ny a pas les difficultés pour venir, pour entrer ce pays-là. Comme Cap-Vert cest pas Europe. Europe cest difficile. Mais moi je préfère Europe, parce que en Europe il y a beaucoup de travail là-bas, pas ici. Mais Cap-Vert cest moins cher, cest facile pour venir ici encore. Il y a les gens sénégalaises qui préfèrent partir en Europe, mais ils nont pas les moyens pour partir à Europe. (Ils) viennent ici et travaillent un peu.

The existence of relatives or friends on the islands is also important for the choice of destination. The importance of networks for migration processes is well documented in the literature since the 1980s (Massey et al., 1998). Networks can lead to the perpetuation of migration itself by offering migrants or potential ones access to social capital and through their central role for the transmission of information. Under the label Relatives or friends are answers with relation to networks summarized (19%). Other motives mentioned are: The decision to migrate to Cape Verde was made by parents or siblings and not by the migrant himself (4%), in comparison to the higher value of the Cape Verde Escudo[18] (4%) and the peaceful and calm situation on the archipelago (6%). The listed priorities, however, not imply that other categories or aspects which werent mentioned by a particular migrant do not have an impact on the decision to migrate and to which destination[19].

When asked who was involved in the decision making, 65% of the questioned Senegalese stated that they took the decision by themselves, and only 16% involved their families. For the remaining 19%, parents or siblings decided on the migration to Cape Verde. It could be expected that circumstances under which the decision was taken, by the migrant alone, together with or solely by his family, is related to the migrants age or his civil status, but the results of the survey do not show such correlations. This result is in so far surprising as it contradicts the prevalent image of migration as a household decision, as suggested for example by NELM and sustainable livelihood approaches. Statements by two fathers, who did not want their son to migrate, also suggest that in some cases the decision was not taken on a household basis.

The life and work of Senegalese in Sal Rei

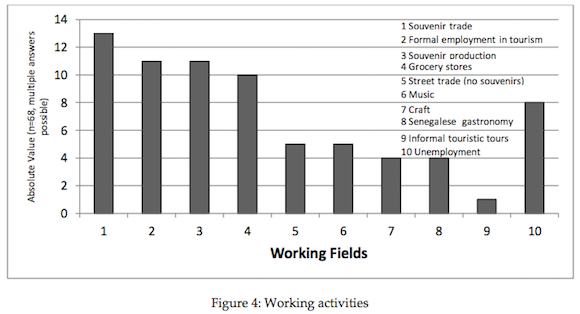

The different labour activities of Senegalese migrants as well as other aspects of their daily life in Sal Rei are important in order to understand the flow of remittances. The presented data are both the result of the questionnaire survey and problem-centred interviews. Figure 4 shows the different working fields in which Senegalese are active. The results do not represent a ranking, but rather demonstrate the variety of employment activities[20]. Nevertheless it is possible to identify some of the most important employment sectors. The result shows that a great part of the Senegalese work in an area related to tourism (Category 1, 2, 3, 5 and 9). Common for many types of employment is an uncertainty and irregularity of income[21], since revenues are often connected directly or indirectly to tourism with its seasonal fluctuation, and in many cases not only irregular but also low. Souvenir trade offers a source of income for many Senegalese, not only through the trade itself, but also through the production. Almost 40% of the surveyed Senegalese work either in the trade or production of souvenirs. It is difficult to estimate the income for souvenir traders[22]. Most souvenir traders said that their income varies during the year, and did not want to name any amount. Only a few stated that they gain roughly between 150 and 300 EUR per month.

Formal employment, for example as cook, launderer or concierge in hotels, is another important employment field. Senegalese who work in hotels or restaurants stated that they earn from 160 up to 380 EUR per month. The average salary lies between 200 and 250 EUR per month. Formal employment has undoubtedly the advantage of a certain security, but some souvenir traders stated that they prefer their work due to a possible higher income.

High costs of

living in Sal Rei also need to be considered. Most Senegalese migrants reside

in the neighbourhood Barraca, where by far the biggest part of migrants, both

internal and international, lives. Land owners can charge high

rents due to a scarcity of

affordable housing. The rental prices vary and in cases, which are known by the

author, Senegalese pay from 80 up to 120 EUR

per month for one room in Barraca. Often three to five migrants live together

in one room or house in order to share the high costs for housing. High food

prices are a further burden on the island, where almost everything needs to be

imported and costs of living are among the highest of Cape Verde. Many migrants

spend a great part of their income to cover their basic needs, which they

perceive as one of their main problems, in addition to the already described

insecurity of income and employment. High expenses and economic problems not

only have an impact on the migrants lives in Sal Rei, but also on the ones of

their relatives at home, since they affect the flow of remittances and need to

be considered in the following analysis of remittances.

The flow of remittances

Out of the 68 migrants who participated in the survey, only five did not send any money at all to a person in Senegal, due to unemployment, low revenues or their short stay in Cape Verde. Out of the 63 who send money, 41 do it once a month, seven every two to three months and five more than once a month. The other ten persons stated that they send money irregularly. There seems to be no specific pattern like the kind of work or the salary which the migrant receives in regard to the frequency. For example the ten people who send money irregularly show different characteristics regarding these aspects. All of them stated that the frequency depends on the success at work. Three of them were unemployed, three worked in one of the big hotel complexes and received a fixed salary every month and four worked in the informal economy with changing monthly earnings. This suggests that besides income and kind of work other aspects influence the willingness to send money, for example the satisfaction of own needs and wishes, but also the social and familial situation on the island, if the migrant is alone or if he lives with his wife and children. Although more than half of the migrants stated that they send money once a month, whether all of them do it exactly each month of the year remains questionable. Considering the irregularity of revenues it is likely that a migrant needs more than one month to earn enough. In some cases the frequency stated by migrants also differs from the one stated by their relatives in Senegal.

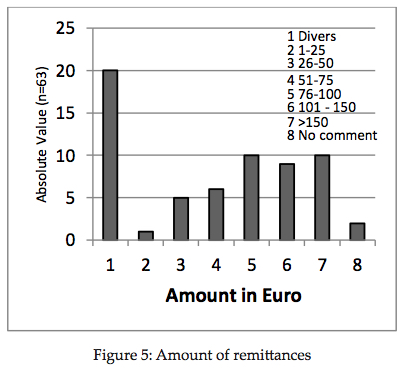

The analyses of the amount of the remittances (Figure 5) shows not only a great variety, but also that about one third of the surveyed Senegalese send different amounts each time[23]. As reason for this diversity all but one migrant stated that it depends on how much they earn.

It is no surprise that with a great part of the Senegalese community on Boa Vista working in the informal economy and in the tourism sector with its cyclic characteristic, both amount and frequency are not constant. When asked if the amount changed generally over the last two years, if it became less or more, 37 out of the 63 migrants confirmed the question. A decline as a consequence of growing difficulties or a higher concurrence was declared by 19 migrants, while one stopped completely to send money. Six Senegalese stated that they send currently more, because they earn more than before or as a response to an increase of prices or other difficulties in Senegal. A decline of amount and frequency was also mentioned by most families in Senegal. Two families in Pikine with migrants working as street vendors on the island of Santiago, explained that they did not receive any money in the last six to nine months.

The case of Mbaye[24], a 40 year old Senegalese who was born in Dakar and already migrated both internal and international before moving to Praia in 2004 also exemplifies the variability of the flow of remittances between Sal Rei and Senegal. After some time working as a street vendor, Mbaye was hired as a painter and sent to Boa Vista in 2005. During the boom years of the building industry he managed the painting of a few big hotel complexes, gaining several thousand EUR per contract, until he had problems with his Italian employer in 2010. Five Western Union transfer vouchers from the period 2008-2011, which he showed, recorded respectively remittances worth 200 to 300 EUR. The dates of the transactions suggest that he saved money for several months before he sent it to his family. According to both Mbaye and his brother the amount of the remittances diminished strongly since 2010. A comparison of his living situation in 2009 and 2012 also indicates that his economic situation worsened during the three years. When the author first met him in 2009, he rented an apartment in one of the better houses in Barraca. In 2012 he lived together with his wife in a small room, for which he paid 10.000 CVE[25] per month. After he lost his work as a painter he took different employments in hotels and at the moment of the fieldwork was working as a photographer for one of the hotels, gaining 300 EUR per month, which enabled him to send 50 EUR to his parents for the alimentation of his son[26]. Only occasionally he sent money for the rest of the family. The author was able to observe one of these occasions, while meeting Mbayes cousin in Dakar. Mbaye called his cousin to inform him, that he had just sent about 75 EUR so that his father could pay for a ram for Tabaski.

The flow of remittances is mainly directed to family members. Fifty-five of the 63 Senegalese send money to their parents. Twenty-five husbands transfer money to their spouses and five named their children as recipient. Brothers (14) and sisters (5) are further recipients of remittances. Only two migrants stated that a person outside their family receives money from them. In 33 cases the migrant sends money to more than one of the stated categories. Remittances in form of material goods or food, as described for example by Lobo (2008) in the case of female emigration from Boa Vista or by Diagne & Rakotonarivo (2010) in their study of remittances from Europe and other African countries to the Dakar region, are not common. In comparison to Senegal prices for goods and food products are high in Cape Verde, which may be a reason for the preference of monetary transactions.

Finally the usage of the remittances should be analysed. The literature suggests that remittances are used to cover regular basic expenses, make investment and optimise livelihood security, especially in regard to food security. The findings of the fieldwork confirm these suggestions partly. When asked for which purposes they think their relatives use the money, most migrants mentioned regular expenses, above all with regards to alimentation, but also for education, payments of rent, electricity or water and medical bills. Considering the great percentage of household income which is used to buy food in Senegal[27], this is no surprise.

The fieldwork in Dakar and Diourbel confirmed the migrants perception that a high percentage of remittances is used to buy food, especially the basic food rice and to a lesser degree for other basic expenses. The impact of the remittances on food security differs, which of course not only depends on remittances, but also on other income sources of the household. When a household strongly depends on the money a migrant sends, the contribution of remittances for the alimentation is high[28]. However, these households also suffer the most if they do not receive any or less money from the migrant as the following examples of two households demonstrate. The first example is a household in Diourbel. According to the mother of a souvenir trader in Sal Rei the remittances which her son sends became less in the last years. While before her son sent money every month, she receives now only every two months with a maximum of roughly 75 EUR. In the case that the money is not sufficient, the family needs to reduce the number of meals per day. Also the second example, one of the already mentioned households in Pikine shows how the discontinuation of remittances can lead to a reduction of meals. In the past the mother received money from her son in Salvador, and from her son-in-law, who lives in Italy. Currently both do not send any money. While before the mother could buy one sack of rice every month, she needs now to calculate everyday how much money she has and buys a small amount of rice on a daily basis.

Only 13 migrants stated that the remittances are partly used for investment and here all but one invest in housing/land. Most other surveyed persons would like to invest, and also here the construction of a house is the priority, but they stated that their income is insufficient. Investment in housing does not only serve the improvement of living conditions, it is also a possibility to demonstrate the success of the migration. The following interview extract refers to the reputation as one raison for investment. According to the migrant all Senegalese who live abroad are preoccupied with the building of a house which would increase his reputation in the community.

Construire sa maison, parce que ça cest essentiel. Le Sénégalais, [ ] sa préoccupation dabord cest davoir une maison, quon dise: Voilà, ça sappelle un Monsieur. Cest pour le monsieur qui a été dans un autre pays.

Besides regular remittances, 53 out of the 63 migrants stated that they send money in the situation of crises[29]. Here the distribution of the use of the remittances shows a different picture. Health problems and related medical expenses, like medicine or hospital visits, are the main reasons and were mentioned by 47 migrants as a case of emergency in which they send money home. Furthermore, 11 Senegalese said that they send money in cases of food insecurity. Other cases of emergency were connected to basic needs, named by six, and financial problems, named by five migrants. Developments in communication technologies and fast transfer system like Western Union, which is the most common form of transferring money, allow the migrants to react without great delay in cases in which the family needs financial support fast.

Remittances are not only used to cover basic needs and to cope with crises. Forty-two Senegalese are sending money for festivities. Here Muslims fests like Tabaski are the most important cause to remit, stated by 38 migrants, followed by marriages (14) and name giving ceremonies (11). Migrants often send larger amounts for Tabaski than they usually do, which suggests that they derive a high prestige from the remittances for these special occasions. Like the building of a house, remittances can be important for the migrants reputation.

Conclusion

The analysis of motives for both, emigration from Senegal and immigration to Cape Verde shows that decisions to migrate are strongly based on economic aspects. This includes existing ones, but also expected economic advantages of Cape Verde. The results of both, the questionnaire survey and the problem-centred interviews suggest that employment conditions and other economic factors are predominant as motives for the migration. A closer analysis, however, indicates that it is too narrow a perspective to explain migration only with economic problems in Senegal and economic advantages in Cape Verde. Migration networks, the relatively simple legal entry in Cape Verde combined with lower costs related to migration, shape the migration process as well. Furthermore social and cultural aspects, for example the common perception of migration and migrants, which are often connected with positive attributes in Senegal, can be further motives for a migration.

The migration is often connected with the desire or obligation to support the family, but also can be a means to escape this obligation. As some of the examined cases show, these two aspects do not necessarily exclude each other and can be equally important for the decision to migrate. A young unmarried Senegalese may emigrate in order to gain some economic independence and to save some money, but at the same time it is important for him to show respect to his parents by sending money. The results also suggest that the decision to migrate is often taken by the migrant alone, and not by the household. This seems unlikely considering family structures in Senegal, and it remains questionable if really that many migrants decided alone to migrate and are as independent as they declared to be. Further research is necessary to validate this finding.

Remittances are an important income source and part of strategies to diversify sources of revenue, but the result of the fieldwork suggests that not only the amount but also the frequency varies, since the flow of remittances is strongly influenced by an irregularity of income and relatively low revenues combined with high living cost. The money Senegalese migrants send is mainly used to satisfy basic needs, particularly alimentation. Hereby remittances can improve the food security of a household, however, fast conclusion or generalisations cannot be made about this relation. An increase of food security is difficult to achieve if the source of income, in that case the money migrants send, is itself not secure. The transmission of money in cases of illness or scarcity of food confirms the suggestion that remittances are an important safety net in situation of crises and part of a strategy to cope with risks. Migrants can act fast if relatives need money to cover medical bills or pay for medicine and transfer money via Western Union. It seems that remittances are in general as important for the day to day survival of the household as in situation of risks. Remittances also have a specific significance in relation to Muslim holidays, above all for Tabaski.

The construction of a house is also for many migrants in Boa Vista a desire and the main area of investment, but only a few are able to do so. The empirical data suggests that investments in economic activities are insignificant. A relative low value of remittances and the necessity to satisfy basic needs first, impede investments. In this context and in general with regards to remittances it is important to consider the medium range of the migration and already described irregularity of revenues in Sal Rei. Although higher salaries, a stronger currency and a more developed tourism sector permit higher revenues in comparison to Senegal, they are not that high to allow the migrants send large amounts. In addition to limited revenues, high costs of living hinder migrants to send bigger amounts or to save for greater investments. The empirical data show that migration, and more precisely remittances, can improve the well-being of migrant households, but, considering the irregularity of both the frequency and the amounts of remittances, their impact on overall development should not be overestimated.

References

Adams, R., & Page, J. (2005). Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Development, 33(10), 1645-1669. [ Links ]

Adepoju, A. (2000). Issues and recent trends in international migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Social Science Journal, 52(165), 383-394. [ Links ]

Adepoju, A. (2004). Trends in international migration in and from Africa. In Massey, D. S., & Taylor, J. E. (Eds.), International migration - Prospects and policies in a global market (pp. 59-76). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Adepoju, A. (2006). Internal and international migration within Africa. In Kok, P., Gelderblom, D., Oucho, J. O., & Zyl, J. V. (Eds.), Migration in South and Southern Africa. Dynamics and determinants (pp. 26-46). Cape Town: HSRC. [ Links ]

Åkesson, L. (2008). The resilience of the Cape Verdean migration tradition. In Batalha, L., & Carling, J. (Eds.), Transnational archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean migration and diaspora (pp. 269-283). Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

ANSD. (2013). Situation économique et sociale du Sénégal en 2011. Dakar: Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie. [ Links ]

Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27(12), 2021-2044. [ Links ]

Carling, J., & Åkesson, L. (2009). Mobility at the heart of a nation: Patterns and meanings of Cape Verdean migration. International Migration, 47(3), 123-155. [ Links ]

Carling, J., & Batalha, L. (2008). Cape Verdean migration and diaspora. In Batalha, L., & Carling, J. (Eds.), Transnational archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean migration and diaspora (pp. 13-31). Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

De Haan, A. (1999). Livelihoods and poverty: The role of migration - A critical review of the migration literature. The Journal of Development Studies, 36(2), 1-47. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. (2006). Migration, remittances and regional development in southern Morocco. Geoforum, 37(4), 565–580. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. (2007). Remittances, migration and social development - A conceptual review of the literature. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. [ Links ]

Diagne, A., & Rakotonarivo, A. (2010). Les transferts des migrants sénégalais vers la région de Dakar: Ampleur et déterminants. MAFE Working Paper no. 9. Paris: Institut National dEtudes Démographiques. [ Links ]

Diop, M.-C. (2008). Présentation: Mobilités, État et societé. In Diop, M.-C. (Ed.), Le Sénégal des migrations: Mobilités, identités et societés (pp.13-36). Paris: Karthala. [ Links ]

DRC. (2007). Global migrant origin database. Retrieved June 8, 2014, from Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty: http://www.migrationdrc.org/research/typesofmigration/global_migrant_origin_database.html [ Links ]

ECOWAS - SWAC/OECD. (2006). Atlas on regional integration in West Africa. [ Links ]

Faist, T. (2011). Unravelling migrants as transnational agents of development: A contribution to the emerging research field of the transnational social question. In Faist, T., & Sieveking, N. (Eds.), Unravelling migrants as transnational agents of development - Social spaces in between Ghana and Germany (pp. 5-27). Berlin, Wien, Zürich: LIT Verlag. [ Links ]

Flahaux, M.-L., Beauchemin, C., & Schoumaker, B. (2010). Partir, revenir: Tendances et facteurs des migrations africaines intra et extra-continentales. MAFE Working Paper no. 7. Paris: MAFE. [ Links ]

Gerdes, F. (2007). Country profile - Senegal. Working paper series Focus Migration no. 10. Hamburg Institute of International Economics. [ Links ]

Hampshire, K. (2002). Fulani on the move: Seasonal economic migration in the Sahel as a social process. Journal of Development Studies, 38(5), 15-36. [ Links ]

Hyden, G. (2001). Moral economy and economy of affection. In Smelser, N. J., & Baltes, P. B. (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 10021-10024). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [ Links ]

INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatística). (2011). Resultados definitivos do RGPH 2010. Praia: INE. [ Links ]

INE. (2014a). Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Cabo Verde. Retrieved February 18, 2014, from http://www.ine.cv/actualise/dadostat/files/2cf36cb9-97ef-4a48-8e10-b6000ac2710 3evolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20dos%20principais%20indicadores%20das%20contas%20nacionais,%202001%20a%202008.pdf [ Links ]

INE. (2014b). Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Cabo Verde. Retrieved February 18, 2014, from http://www.ine.cv/actualise/dadostat/files/12a520fa-0345-42ce-a69e-0d357e3b04 ceevolu%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20de%20estabelecimentos,%20capacidade%20e%20pessoal%20ao%20servi%C3%A7o,%20%201999%20a%202011.pdf [ Links ]

IOM (International Organization for Migration). (2010). Migração em Cabo Verde - Perfil nacional 2009. Geneva: IOM. [ Links ]

Lacroix, T. (2011). Migration, rural development, poverty and food security: A comparative perspective. Oxford: International Migration Institute. [ Links ]

Land, V. van der, & Fourier, J. (2012). Focus Senegal. In Hummel, D., Doevenspeck, M., & Samimi, C., Climate change, environment and migration in the Sahel - Selected issues with a focus on Senegal and Mali. Micle Working Paper no. 1. Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

Latapí, A. E. (2012). Migration vs. development? The case of poverty and inequality in Mexico. Migration Letters, 9(1), 65-74. [ Links ]

Lessault, D., & Mezger, C. (2010). La migration internationale sénégalaise - Des discours publics à la visibilité statistique. Paris: MAFE. [ Links ]

Lindley, A. (2006). Migrant remittances in the context of crisis in Somali society - A case study of Hargeisa. London: Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute. [ Links ]

Lobo, A. d. (2008). And when the women leave? Female emigration from Boa Vista. In Batalha, L., & Carling, J. (Eds.), Transnational archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean migration and diaspora (pp. 131-144). Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Lutz, H. (2010). Gender in the migratory process. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), 1647-1663. [ Links ]

Marcelino, P. F. (2011). The new migration paradigm of transitional African spaces: Inclusion, exclusion, liminality and economic competition in transit countries: A case study on the Cape Verde islands. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic. [ Links ]

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouc, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1998). Worlds in motion - Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

McDowell, C., & De Haan, A. (1997). Migration and sustainable livelihoods: A critical review of the literature. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. [ Links ]

McDowell, L. (2009). Moral economies. In Kitchin, R., & Thrift, N. (Eds.), International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 185-190). Amsterdam: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Mezger, C., & Beauchemin, C. (2010). The role of international migration experience for investment at home: The case of Senegal. Paris: MAFE. [ Links ]

Mohapatra, S., Ratha, D., & Silwal, A. (2011). Outlook for remittance flows 2012-14. Migration and Development Brief No. 17. December. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Portes, A. (2007, March). Migration, development, and segmented assimilation: A conceptual review of evidence. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 610, pp. 73-97. [ Links ]

Quartey, P. (2006). The impact of migrant remittances on household welfare in Ghana. Nairobi: African Economic Research Consortium. [ Links ]

Ramamurthy, B. (2003). International labour migrants: Unsung heroes of globalisation. Sida Studies no. 8. Stockholm: Sida. [ Links ]

Rapoport, H., & Docquier, F. (2005). The economics of migrants remittances. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labour. [ Links ]

Riccio, B. (2005). Talkin about migration - Some ethnographic notes on the ambivalent representation of migrants in contemporary Senegal. Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien 8, pp. 99-118. [ Links ]

Riccio, B. (2008). Les migrants sénégalais en Italie. Réseaux, insertion et potentiel de co-développment. In Diop, M. (Ed.), Le Sénégal des migrations: Mobilités, identités et societés (pp. 69-104). Paris: Karthala. [ Links ]

Salzbrunn, M. (2008). Glocal migration and transnational politics: The case of Senegal. Global Migration and Transnational Politics Working Paper. Arlington, Virginia: Center for Global Studies, George Mason University. [ Links ]

Scott, J. C. (1976). The moral economy of the peasant - Rebellion and subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Sheffer, G. (2006). Diaspora politics: At home abroad. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Smith, L. (2007). Tied to migrants - Transnational influences on the economy of Accra, Ghana. Leiden: African Studies Centre. [ Links ]

Smith, L. C., & Subandoro, A. (2007). Measuring food security using household expenditure surveys. Food Security in Practice technical guide series. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. [ Links ]

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75(2), 173-178. [ Links ]

Stark, O., & Taylor, J. E. (1989). Relative deprivation and international migration. Demography, 26(1), 1-14. [ Links ]

Tall, S. M. (2008a). La migration internationale sénégalaise: Des recrutements de main-duvre aux pirogues. In Diop, M.-C. (Ed.), Le Sénégal des migrations: Mobilités, identités et societés (pp. 37-67). Paris: Karthala. [ Links ]

Tall, S. M. (2008b). Les émigrés sénégalais en Italie - Transferts financiers et potentiel de développement de lhabitat au Sénégal. In Diop, M.-C. (Ed.), Le Sénégal des migrations: Mobilités, identités et societés (pp. 153-178). Paris: Karthala. [ Links ]

The World Bank. (2011). Migration and remittances factbook 2011 (Second edition). Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Zezza, A., Carletto, C., Davis, B., & Winters, P. (2011). Assessing the impact of migration on food and nutrition security. Food Policy, 36(1), 1-6. [ Links ]

Recebido a 14 de março de 2014; Aceite a 17 de abril de 2015

NOTES

[1] The actual figure is higher since undocumented migrations are not reflected in official statistics.

[2] De Haas (2007, p. 1) criticize the reduction on economic aspects and the ignorance of a wide range of other important aspects of development like health or education. Migration often affects social issues like ethnic or gender relations (Lutz, 2010; De Haas, 2006) or political processes (Salzbrunn, 2008; Sheffer, 2006). Furthermore De Haas (2007) and Faist (2011) criticize the absence of a debate about the meaning of development in migration studies and the dominance of Western models of development with their tendency to focus on gross income indicators.

[3] New economic of labour migration (NELM) emerged mainly in the American research context in the 1980s with the key aspect that migration decisions are not made by individuals as a result of cost-benefit calculations with the aim to maximize expected incomes, but by larger units of related people in order to minimize risks and to loose constraints associated with market failures. Furthermore relative deprivation is an important factor for migration decisions.

[4] Sustainable livelihood approaches examine household strategies for the diversification of livelihoods in order to cope with risk situation and to guarantee the survival. Migration, temporary or permanent, is one of three main strategies to achieve this and especially important where other forms of livelihood diversification are absent.

[5] The concept of moral economy was developed in the research of traditional, peasant societies (e.g.: Scott, 1976), where the social relations of production, exchange and waged labour are influenced by customs, culture, and traditions (McDowell, 2009, p. 187).

[6] The field work was conducted within the framework Projeto PTDC/AFR/104597/2008, of the CEA-ISCTE and financed by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT, Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology).

[7] Fieldwork was done in Sal Rei, the principal town of Boa Vista in June/August 2009 and in May/June 2012 and in Senegal in September/October 2012.

[8] All but three respondents were men. Despite the high proportion of men in the population of Senegalese migrants in Boa Vista, it wasnt intended to interview only three female migrants. The origin and gender of the author need to be considered at this point. As a European male contacting and gaining the trust of women was not easy and can partly explain the low number of female participants. Furthermore, working and private obligations may be a reason that for some women time was restricted and they did not want to participate in the survey. As a consequence the collected data focus more on the role of men, but hereby also reflects the dominance of male Senegalese in the surveyed migration system. It must be assumed that with a higher female percentage within the survey some questions would have led to different results.

[9] The real GDP increased annually about 6.5 % between 2000 and 2008 (INE, 2014a).

[10] Between 1999 and 2011 the number of touristic establishments increased from 79 to 195, the number of beds has more than quadrupled from 3.165 to 14.076 and the number of employees in the touristic sector increased from 1.516 to 5.178 (INE, 2014b).

[11] Official statistics about immigration in Cape Verde vary and need to be treated with caution. According to the INE around 9.000 migrants from ECOWAS countries live on the islands and 5.500 Guinea-Bissauans alone count for about 38% of the total foreign population (INE, 2011). For an overview of different statistics, its sources and problems see: IOM (2010).

[12] Authors like Carling & Åkesson (2009) or Marcelino (2011) also suggest that the archipelago, which is located about 500 km west of the coast of Senegal, has become increasingly a transit point for the migration to Europe.

[13] In 2011 Boa Vista replaced Sal as the island with the most tourist entries and overnight stays. The number of tourist entries on the island increased from 9.402 in 2000 to 184.878 in 2011 and the number of overnight stays from 63.161 to 1.334.108 in the same period of time (INE, 2014b).

[14] During her presentation at the 5th European Conference on African Studies Clementina Furtado from the University of Cape Verde referred to a statement made by the Senegalese ambassador in Cape Verde, that about 5.000 Senegalese live in Cape Verde.

[15] Names are changed in order to guarantee anonymity.

[16] Stereotypical images of African immigrants as persons who steel jobs, lead to low salaries and are responsible for the increase of criminal activities are widespread. For a deeper analysis of the transformation of the Cape Verdean society and the problems, which come along, see Marcelino (2011).

[17] The protocol on Free Movement of Persons, Residence and Establishment permits nationals of the fifteen ECOWAS member states the free movement in the regional bloc (ECOWAS-SWAC / OECD, 2006).

[18] 1 CVE = 5.58 XOF (Franc CFA). Both currencies are linked by a fixed exchange rate to the EUR.

[19] None of the respondents mentioned, at least not directly, personal problems or conflicts within the family or community as reasons for the migration. This does neither mean that they do not influence the decision to migrate nor that they are not relevant for the questioned migrants. It is more likely that social conflicts were not mentioned in presence of the author. Answers summarized under the category Personal savings may refer partly to problems in the family.

[20] A change in the survey sample would probably lead to a different picture. For example a higher percentage of female migrants in the survey could result in a greater importance of formal employment in tourism and informal Senegalese gastronomies.

[21] The only exceptions are formal employment in the tourism sector and for some degree also craftsman like carpenters, mechanics or construction workers.

[22] There are two types of souvenir traders, mobile ones and the ones who sell products in a shop. Many of the shop owners started as a street vendor until they earned the necessary financial resources. Contacts to the Cape Verdean authorities are probably also a factor.

[23] The amount of the remittances is in no correlation with the frequency. A person may send fewer times, but a higher amount each time. The list of the different amounts of the transaction only indicates the variety of amounts which migrants send.

[24] Mbaye returned to Dakar in March 2014, explaining his decision to leave Cape Verde with growing economic difficulties in Sal Rei. His cousin mentioned that Mbaye also met the desire of his father by returning.

[25] 91.84 EUR.

[26] His wife went to Boa Vista for the first time in 2009, but returned during her pregnancy to Senegal, before she moved again to Sal Rei in December 2011. Their only son stayed with Mbayes mother in Pikine.

[27] Households spend averagely 61 percent of their income on food in Senegal. In urban areas the average is slightly lower with 55 percent compared to 66 percent in rural areas (Smith & Subandoro, 2007, p. 84).

[28] According to household budget surveys households in Senegal depend strongly on remittances and cover between 30 and 80% of their needs with money emigrants send (Adepoju, 2000, p. 385).

[29] A distinction between regular remittances and those who are send in cases of emergency is, if at all, only partly possible. It remains questionable if money for emergencies or festivities is send in addition to regular remittances. It seems more likely that they are sent instead of regular remittances, or that in these cases regular remittances are used to cover these expenses too, although the amount which the migrants send may increase.