Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista de Gestão dos Países de Língua Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1645-4464

Rev. Portuguesa e Brasileira de Gestão vol.13 no.3 Lisboa set. 2014

CONFERÊNCIA

Social tourism and senior university in Portugal: a research proposal

Turismo social e Universidades da Terceira Idade: uma proposta de investigação

Turismo Social y Universidades de la Tercera Edad: Una propuesta de investigación

Sonia DahabI; Teresa MannebachII

IPhD in Economics, Economics Department, Yale University. Associate Professor, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, School of Business and Economics, Travessa Estevão Pinto, s/n, 1099-032 Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: sdahab@novasbe.pt

IIMaster in Management, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, School of Business and Economics, 1099-032 Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: moana.mannebach@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to fill a literature gap and to analyze empirically senior universities in Portugal related to the impact of experimental learning on courses offered. Focus will be given to the elderly population motivations to experiment new cultural expressions and the impact this process may have on their cognitive abilities/culture intelligence. Social tourism becomes increasingly important given the lack of elderly economic means to support travel expenses and ways to save for leisure time after retirement. Senior university and social tourism can together offer this possibility. The first part represents an introduction to the topic of social travel. The second part focuses on the major conceptual aspects – culture, experimental knowledge, cultural intelligence adapted to senior universities courses – to support and justify the hypotheses to be tested.

Key words: Portuguese Senior University, Culture and Travel, Social Tourism, Experimental Learning

RESUMO

O trabalho tem como objetivo preencher uma lacuna na literatura sobre o impacto do ensino experimental nas universidades da terceira idade em Portugal, através do estudo empírico dos cursos oferecidos. Será dado particular relevo às motivações do segmento sénior em experimentar novas expressões e experiências culturais e ao impacto que estas possam ter na sua capacidade cognitiva/inteligência cultural. O turismo social tem-se tornado particularmente importante, tendo em conta as crescentes carências económicas dos mais idosos em financiarem as suas viagens e pouparem para atividades de lazer. As universidades seniores e o turismo sénior podem ser uma maneira de viabilizar estas novas formas de aprendizagem cultural. O trabalho faz uma introdução ao tópico do turismo social e de seguida trata dos principais conceitos: cultura, conhecimento experimental, inteligência cultural adaptados aos cursos das universidades seniores para fundamentar e justificar as hipóteses testadas.

Palavras-chave: Universidade Sénior, Cultura, Turismo Social, Aprendizagem Experimental

RESUMEN

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo llenar un vacío en la literatura sobre el impacto de la enseñanza experimental en las universidades de la tercera edad en Portugal, a través del estudio empírico de los cursos ofrecidos. Se prestará especial atención a las motivaciones del segmento de la tercera edad en probar nuevas expresiones y experiencias culturales y el impacto que pueden tener en su capacidad cognitiva/inteligencia cultural. El turismo social es cada vez particularmente más importante, dadas las crecientes dificultades económicas de las personas mayores en financiar su viaje y ahorrar para las actividades de ocio. Las universidades y el turismo de la tercera edad pueden ser una manera de permitir estas nuevas formas de aprendizaje cultural. Este trabajo hace una introducción al tema del turismo social y luego se dirige a los conceptos centrales: la cultura, el conocimiento experimental y la inteligencia cultural, adaptados a los cursos de las universidades de la tercera edad, para fundamentar y justificar las hipótesis probadas.

Palabras clave: Universidad Tercera Edad, Cultura, Turismo Social, Aprendizaje Experimental

One way to deliver welfare results while reducing the costs of providing benefits is through social tourism. Social tourism is a form of tourism that offers tourism experiences to groups who cannot be part of regular tourism due to several constraints (Carneiro et al., 2013). Over the years, a permanent platform has been developed – International Social Tourism Organization (ISTO) – where social tourism issues can be discussed on an international level. This platform stresses the relevance of social tourism in general (Bélanger and Jolin, 2011). Additionally, social tourism has gained enormous momentum due to various programs such as “Chèques-Vacances” in France[1], IMSERSO in Spain[2], and Calypso of the European Commission (Minnaert et al., 2011).

In general, the development of intercultural interaction, the stimulation of peace and understanding, personal benefits, economic growth, and the prosperity for tourism destinations are benefits of tourism (Carneiro et al., 2013). However, social tourism is said to generate both social as well as economic benefits (Minnaert et al., 2011). Particularly, social impact is reached through an increase in self-esteem, improvement in family relations, widening of travel horizon, more pro-active attitudes to life, participation in education and employment.

The most frequent motivations for senior travelling in Portugal are relaxing (including wellness), routine break (including shopping), social interactions (relatives and broader circles), natural endowments (with physical activity or not) and cultural reasons such as living different cultural experiences, heritage, and monuments. Those motivations extend to senior students through a study of Portuguese senior universities in 2006 (Neves, 2009).

Specific analysis of Portuguese senior motivations related to study travelling and educational vacations are still missing in the literature. According to Ginevièius et al. (2007), they are very popular among German seniors. They reveal enormous motivation to learn a high range of topics and a strong desire to experiment new cultural environments. This segment is characterized by a high level of income with wide previous experience on travelling. It is considered a high demanding market in quality on several levels: comfortable and friendly hospitality, good social environment, pleasant climate, and educational/cultural content. Nimrod and Rotem´s (2010) study about Israeli seniors highlight the cultural interest and find that major motivations are educational experience, city visits with cultural interest, spiritual experience, and entertainment.

Also, the European Commission´s (2011) analysis of European seniors´ (above 55 years old) motivations to choose a destination are mostly related to tangible cultural heritage/monuments but also intangible cultural aspects such gastronomy. They prefer traditional destinies, mostly within Europe.

Seniors travel motivations and socio-economic impact

As remarked by Neves (2009) and Niron (2008) senior motivations vary according to the level of health and literacy and the overlapping of interests are conceptually explained by Uriely (2005) in an analysis of tourist experience. Recently, Carneiro et al. (2013) identified several motivations of elderly to participate in social tourism programs, such as getting away from daily routines, to rest and relax, to improve health and wellness, enjoying novelty seeking, cultural enrichment, living new experiences, socializing, physical outdoor activities, and other nostalgic reasons.

Especially for disadvantaged groups, social tourism can have severe consequences since those groups may regard tourism experiences as a temporary mean of escaping their negative conditions or as a basic human right, which enormously enhance their quality of life. Consequently, it can be stated that the senior market is heterogeneous regarding motivations, with a relevant percentage motivated by cultural and educational experiences, others focused on entertainment and relaxation. It is also important to highlight that hedonistic motives are not detached from intellectual/social life motivations as analyzed by Macker and Ballantyme (2014) and by McCabe and Johnson (2012).

However, economic benefits are represented by sustaining jobs in low seasons and by generating income for host communities. It is important to distinguish between two varying forms of social tourism: visitor-related and host-related. The former is related to an increase of the participation in tourism for disadvantaged groups whereas the latter is aiming at increasing economic benefits of tourism (Minnaert et al., 2009).

More precisely, four different interpretations of social tourism exist which are translated into four models:

- Participation Model: a standard product or service is being offered to social tourism users only;

- Inclusion Model: a standard product or service is being offered to social tourism users in addition to other users;

- Adaptation Model: instead of a standard product or service, a specific provision is being offered to social tourism users only;

- Stimulation Model: a specific provision is being offered to social tourism users in addition to other users.

One example of a disadvantaged group, which could take advantage of social tourism, is elderly. The increasing amount of elderly in Portugal is a trend that should not be taken lightly. In 2011, 19.1% of the Portuguese population was above 65 years old opposed to 13.6% in 1991 (Eurostat, 2014). Common problems among elderly are represented by failing health, economic insecurity, isolation, fear, idleness, abuse, loss of control and lowered self-esteem (Helpageindiaprogramme, 2014). Going further, due to being a common source of distress and hence, an impaired quality of life, loneliness or idleness is the second greatest cause of death among elderly.

Besides, according to Euromonitor (2014, p. 16) and based on OECD data, only 10.5% of the Portuguese seniors above 65 years are below the “50% of the median equalized income”. This shining scenario is quite tortuous since it does not define clearly what type of income measure is used, and eliminates the income concentration effect measured in terms of median. In fact, Portuguese seniors have progressively decreasing disposable income through cuts in pension earnings, social welfare/health programs, and increasing cost in private services for this segment, especially in the health insurance plans.

Besides, the unemployment rate in the segment of over 55 years old is very high and formed by a high level of literacy, INE (2014). Usually a job loss in this age means unforeseen perspective on a new regular placement and the impossibility to retire given that the retirement age is 65 years old. Therefore, this group lives between two difficult dilemmas: young to be capable to produce and yet old, with difficult possibilities to insert itself in society productively.

Senior universities, as a form of social tourism can narrow the bridge between the cultural tourism needs of this segment and add individual and social value to society by offering travelling as a learning tool. This is also the basis for the senior university as a stimulation model.

Senior universities have been establishing all over the world to further counteract the problems faced by the elderly. Among others, common motivational factors for elderly to attend senior university courses are to broaden their scope by learning and acting, to promote self-fulfillment through engagement, to capture the opportunity for inter-age culture, to receive support, and to use feedback for further development (Arnold and Costa, 1994). Moreover, senior universities can be positioned along a continuum ranging from autonomous self-organized models in which the third-agers are both teachers and students because they run classes with topics of their own choice to inter-generational study options which represent pre-shaped study programs.

Portugal can be a very attractive place to foreign senior travellers. It ranks the 13th country in Europe for Travel and Tourism (T&T) including Cultural Tourism and 20th in the world ranking (see Table 1). Besides, the market for late lifers is one of the most promising ones in terms of growth (see Tables 2 and 3). This may allow an interest and opportunity for international senior travel with intercultural programs. The role of Portuguese senior universities programs can be crucial to the economic success of this activity.

To sum up, combining senior universities with social tourism represents a mixture of the adaptation and stimulation model. Offering study trips to places of class topics in senior universities is a provision especially designed for elderly who suffer from immobility and economical weakness. However, those programs will not only benefit the visitors but also the host communities of the destinations. Consequently, while increasing the subjective well-being and hence, the quality of life of elderly, the economic situation of destinations will be enhanced.

The potential and social impact that senior cultural travel market can justify a deeper study of the following items: cultural tourism concept to better understand cultural tourism as a learning tool in the Portuguese senior universities.

Senior universities: culture concept toward cultural tourism and learning

Culture concept

According to Hofstede (1980) culture is the collective programing of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another, giving shape to the interactive aggregate of common characteristics that influences a group’ s response to its environment. This programing process is based on a system of values and norms that are shared among a group of people and that when taken together constitute a design for living.

For Tylor (1871), the most complete anthropological work on culture, analysis of cultural expressions are a complex whole of tangible and intangible human constructs which include knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, customs and any capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.

Given the broadness of cultural expressions, the International Commission on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) extended the concept to embrace “a combination of natural as well as the cultural environment which encompasses landscapes, historic places, sites and built environments, as well as bio-diversity, collections, past and continuing cultural practices, knowledge, and living experiences.” (International Council on Monuments and Sites, 2008).

According to Maslow (1943), learning is understood as techniques of human survival and continuous learning is a precondition for self-actualization. The human life cycle requires different needs, and seniors learning responds not only to self-esteem needs but also to adaptation to new survival techniques. “Acquiring knowledge and systematizing the universe have been considered as, in part, techniques for the achievement of basic safety in the world, or for the intelligent man, expressions of self-actualization” (Maslow, 1943, p. 376).

Pedagogical approaches to senior learning should then be viewed in a broad context of learning experiences. Cultural and educational travels can be an important pedagogical tool. Based on the definition of learning above, senior cultural education is a need to reshape life according to new needs of its life cycle in order to be able to survive socially.

Methodological approach to senior cultural travel and learning

According to Uriely (2005), the academic interest regarding this issue concerns the existential dimension of tourists’ valuations of their personal experiences. Specifically, such analysis focus on tourism motivations and meanings that participants assign to their experiences in light of everyday life in ‘‘advanced’’ industrialized societies. The focus here is on identifying and evaluating major developments in the conceptualization of the experience.

Specifically, by reviewing relevant literature across various topics, including the definition of the tourist role, typologies, authenticity, post modern, and heritage tourism, four developments emerge:

- A reconsideration of the distinctiveness of tourism from everyday life experiences;

- A shift from homogenizing portrayals of the tourist as a general type to pluralizing depictions that capture the multiplicity of the experience;

- Shifted focus from the displayed objects provided by the industry to the subjective negotiation of meanings as a determinant of the experience and

- A movement from contradictory and decisive academic discourse, which conceptualizes the experience in terms of absolute truths, toward relative and complementary interpretations.

This framework can be very useful to qualify and quantify the impact that cultural and educational travels can have on the experience of senior students through courses offered by senior universities that offer the possibility to organize cultural and educational travels to turn the academic knowledge acquired into a holistic experience.

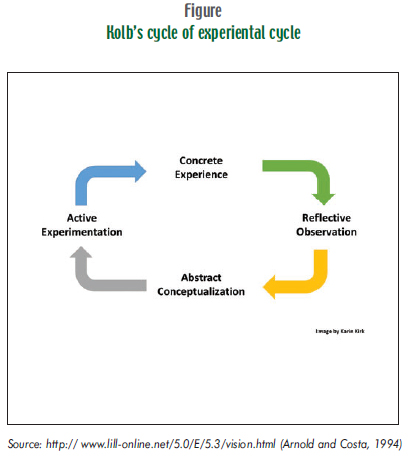

Experiential learning theory was largely diffused by Kolb (1984) (see Figure). The author argues that globalization presents a scenario in which individuals feel the impact of global events, encounter rapid change, and come across more knowledge. Thus, individuals experience increased haste to adapt to this environment. Similar to Maslow´s argument, Kolb (1984) argues that to persist an individual must adapt, and continuous experimental learning is the process to achieve this mean. According to experiential learning theory (ELT), the individual performs or engages in activities by which to respond to the environment in a holistic process.

Learning from experience requires that an individual attends to or examines the experience and then converts it into knowledge. Two divergent or dialectic dimensions influence the adaptation process:

- Concrete experience (CE) and abstract conceptualization (AC) associated with comprehension and

- Active experimentation (AE) and reflective observation (RO) associated with transformation.

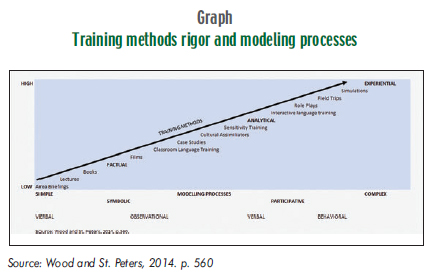

Therefore, the evolution of the learning/training process from a factual to an experimental methodology can be graphically showed as follows:

Wood and St. Peters (2014) empirical research on experimental learning was directed to groups of MBA students with the objective of learning about their cultural intelligence and the impact that short studying trips have on their better management leadership and the role of cultural intelligence on their professional performance.

Although our focus group is composed of senior students and the analysis centers around the impact that cultural educational trips may have on the acquisition of experimental knowledge through courses given by senior universities, the paper methodology and sampling criteria can be adapted to our purpose.

However, to the purpose of our study, holistic knowledge has to contemplate both the academic aspects of the learning process but also the impact of the experimental learning on their behaviour change toward enlargement of social life experience and adaptation, extremely necessary given our concept of culture and senior needs of cultural continuous learning and updating.

Cultural intelligence adapted to senior university courses

Cultural intelligence (CQ) represents an individual’s ability to function in various cultural contexts (Earley and Ang, 2003). CQ reflects a set of capabilities that include metacognition, cognition, motivation and behavior (Ang and Van Dyne, 2008). Metacognition represents a way of thinking that fosters the development of coping strategies; cognition reflects cultural knowledge; motivation consists of efficacy to persist; and behavior is demonstrated in a repertoire of behavioral patterns (Earley and Peterson, 2004; Ng and Earley, 2006; Ang and Inkpen, 2008).

Cognitive CQ combines knowledge attained through education and experience which represent normalized values, behavioral patterns and customs held in various cultures defined by pronounced differences and to exert the effort necessary to learn in an intercultural encounter (Ang and Inkpen, 2008; Ng et al., 2009).

Behavioral CQ represents the ability to respond to various cultural situations by drawing from a well developed repertoire of behavior so as to demonstrate verbal and non verbal proficiency (Ng et al., 2009; Van Dyne et al., 2010).

Recent research pertaining to CQ indicates that CQ is positively and significantly related to all forms of adjustments (Van Dyne and Ang, 2008; Koh and Ng, 2004; Anget al., 2006). Moreover, CQ facilitates cultural judgment and decision-making, well-being, and task performance (Ang et al., 2007; Koh et al., 2010). CQ also alleviates emotional exhaustion and burnout (Tay et al., 2008). Applying CQ to CCT via ELT provides the ability to see whether or how much seniors learn and benefit from cultural and experimental learning.

To employ CQ to experiential learning, Livermore (2008) suggests a model that includes the following: focus or observation as part of metacognitive CQ; action-reflection wherein individuals act on familiar or unfamiliar cues and attempt to make sense; support-feedback that includes affirmation and encouragement to learn from the cultural experience; debrief to deliberately discuss and evaluate the experience; and learning transfer to apply the lessons to different contexts.

Oddou et al. (2000, p. 161) define five global competencies that are responsive to well planned travel experiences:

- Understanding different viewpoints – seeing things from a new perspective;

- Managing uncertainty;

- Being inquisitive and having curiosity or interest in people who are different to oneself;

- Being willing to stretch one’s mental maps; and

- Being perceptive and sensitive to cultural differences.

An individual can enhance CQ through formal preparation (e.g. training) and various types of cross-cultural experiences. Metacognitive CQ reflects a higher order process associated with thinking about thinking (Ang et al. 2007). This capability permits the acquisition and understanding of cultural knowledge to make sense of novel cultural experiences (Van Dyne et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2009). Short-term cross-cultural study tours should provide opportunity to examine cultural assumptions in light of the observed behavioral patterns exhibited by others.

Research Question

Based on the literature review, we can summarize that:

- Senior universities are a need for elderly groups, especially given the income concentrating tendency in Portugal.

- Social tourism can be a stimulation and adaptation model benefiting both elders’ quality of life and society, mostly through dynamization of tourism destinations.

- Elders need to experiment new cultural realities with social interaction.

- Cultural experimentation, through structured course given by senior universities, associated with tourism, may be a very suitable pedagogical tool for this age segment.

Therefore: How far do cultural trips affect experimental learning on courses offered at senior universities

Five hypotheses are initially being proposed:

Hypothesis 1: The experiential learning resulting from short-term cross-cultural study tours will enhance metacognitive CQ

Cognitive CQ combines knowledge attained through education and experience that represent normalized values, behavioral patterns and customs held in various cultures (Ang and Inkpen, 2008). An individual uses schemes or mind maps to ascertain both similarities and differences among cultures and to search for cultural cues to develop accurate expectations (Van Dyne et al., 2007; Koh et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2009). Short-term cross-cultural study tours should provide information as to the similarities and differences among cultures using existing schemes.

Hypothesis 2: The experiential learning resulting from short-term cross-cultural study tours will enhance cognitive CQ

An individual with a strong sense of self-efficacy often reveals a greater willingness to engage with the unfamiliar and avoid withdrawal after facing impediments (Earley, 2002; Earley and Peterson, 2004; Van Dyne et al., 2010). Moreover, this individual also possesses a curiosity toward another culture that functions as a driving force (Ang et al., 2007). Short-term cross-cultural study tours should permit positive, though limited, experiences to build confidence and reinforce a curiosity to pursue additional interactions (Ballantyne and Packer, 2011; Ballantyne et al., 2011).

Hypothesis 3: The experiential learning resulting from short-term cross-cultural study tours will enhance motivational CQ

Ng et al. (2009) argued that behavioral CQ represents a critical factor toward effectiveness, as an individual must possess a broad range of behaviors from which to select. Behavioral CQ is exhibited through the response to cultural stimuli, drawing from learned, and practiced behaviors. Short-term cross-cultural study tours are expected to provide the means by which participants can observe and practice these behaviors, resulting in a broader “repertoire” of behaviors upon which to draw.

Hypothesis 4: The experiential learning resulting from short-term cross-cultural study tours will enhance behavioral CQ

Hypothesis related strictly to cultural tourism in senior universities

The literature review specifically to justify hypothesis 5 and 6 is the result of the analysis of senior motivations to travel and to undertake cultural trips. Several authors who were already cited are implicitly included.

Hypothesis 5: Cultural tourism improves the learning process related to theoretical courses

There is no relationship between cultural tourism and the learning process related to theoretical courses (H0)

- Question: I can remember the theory learned at my university better if I have a practical relation to it – totally disagree to totally agree

- Test: one-sample t-test (one sided) – µ <= 3

- Cultural tourism is a positive aspect to attract people to senior universities in Portugal

Hypothesis 6: Seniors are neutral or less likely to attend senior universities in Portugal when cultural tourism is part of the university´s schedule

- Question: I would attend senior universities in Portugal when cultural tourism is offered – totally disagree to totally agree

- Test: one-sample t-test (one sided) – µ <= 3

- Senior university cultural tourism promotes social and knowledge interactions among seniors

There is no relationship between senior university cultural tourism and social/knowledge interactions among seniors

- Question: I find it easier to communicate with my university colleagues on a trip than within the walls of the university – totally disagree to totally agree

- Test: one-sample t-test (one sided) – µ <= 3

- Senior travel culture tourism has a positive impact on the development of the cultural area visited

Seniors are neutral or less likely to spend money on a coffee, etc. at the area visited during a trip organized by senior universities

- Question: I would spend money on a coffee, etc. at the area visited during a trip organized by my senior university – totally disagree to totally agree

- Test: one-sample t-test (one-sided) - µ <= 3

Methodology

The purpose of this research from hypothesis 1 to 4 is to investigate experiential learning methods for cultivating the four CQ constructs. Specifically, this research investigates the impact of short-term cultural study tours on each of the four CQ constructs. Hypothesis 5 and 6 investigate the importance of adopting experimental learning in senior universities and its socialization effect. Likert scales will be used as well as continuous data. Therefore, structural equations such as Tobit equations will be used. Story (2010) also applies multi-level analysis to methodology to test the impact of global mindset on positive organizations outcomes.

Sampling method

The universe of this study comprised individuals taking courses in Portuguese senior universities that offer experimental learning as part of their pedagogical system. Courses in senior universities that offer the experimental learning methodology will be contacted and interviews will be applied to teacher and students.

The characteristics of the samples will follow a normal distribution of the universe, and personal characterization based on age, sex, occupation and socio-economic situation will first be built. The sampling procedure will obey two basic criteria: age group (up to 55; above 55) and income level (if the information is available).

Two questionnaires will be distributed, before and after travelling. A model of structural equations with Likert scale, binary and continuous variables will be used. A pilot questionnaire will be applied to test the consistency of the model and correlation among variables. We hope that a minimum of 400 valid questionnaires will be available to the significance and robustness of the results.

Conclusion

This paper is a review of the literature and a proposal for future empirical research. Given time constrains; it was not possible to apply the questionnaires to this scholar period. Nevertheless, the need to study empirically the Portuguese and world-wide elderly segment is of major importance to our society.

The longer the life cycle, the greater the need to built mechanisms to maintain an active and healthy mind. The new challenges due to family structure transformations, labor market structure, and urbanization urge to new forms to occupy an elderly growing population eager to learn and enjoy life. Senior universities can be a solution to the problems of socialization and the basic need of culture updating as pointed by Maslow.

References

ANG, S. & VAN DYNE, L. (2008), “Conceptualization of cultural intelligence: definition, distinctiveness, and nomological network”. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, pp. 3-15. [ Links ]

ANG, S. & INKPEN, C. (2008), “Cultural intelligence and offshore outsourcing success: a framework of firm-level intercultural capability”. Decision Sciences, 29, 3, pp. 337-358. [ Links ]

ANG, S.; VAN DYNE, L. & KOH, C. (2006), “Personality correlates of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence”. Group and Organization Management, 31, 1, pp. 100-123. [ Links ]

ANG, S.; VAN DYNE, L.; KOH, C.; NG, K.-Y.; TEMPLER, K. J.; TAY, C. & CHANDRASEKAR, N. A. (2007), “Cultural intelligence: its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation, and task performance”. Management and Organization Review, 3, pp. 335-371. [ Links ]

BALLANTYNE, R. & PACKER, J. (2011), “Using tourism free choice learning experiences to promote environmentally sustainable behaviour: the role of post-visit action resources”. Environmental Education Research, 17(2), pp. 201-215. [ Links ]

BALLANTYNE, R.; PACKER, J. & FALK, J. (2011), “Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: testing short and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modelling”. Tourism Management, 32(6), pp. 1243-1252. [ Links ]

BÉLANGER, C. & JOLIN, L. (2011), “The International Organisation of Social Tourism (ISTO) working towards a right to holidays and tourism for all”. Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 14, Issue 5. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, M. J.; EUSÉBIO, C.; KASTENHOLZ, E. & ALVELOS, H. (2013), “Motivations to participate in social tourism programmes: a segmentation analysis of the senior market”. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 352-366. [ Links ]

DONTHU, N. & BOONGHEE, Y. (1998), “Cultural influences on service quality expectations”. Journal of Service Research, vol. 1(2), pp. 178-186. [ Links ]

EARLEY, P. C. (2002), “Redefining interactions across cultures and organizations: moving forward with cultural intelligence.” Research Organization Behavior, vol. 24, pp. 1-345. [ Links ]

EARLEY, P. C. & PETERSON, R. S. (2004), “The elusive cultural chameleon: cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager”. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(1), pp. 100-115. [ Links ]

EUROMONITOR INTERNATIONAL (2014), The Global Later Lifers Market. How the Over 60s Are Coming in their Own. May. [ Links ]

EUROMONITOR (2013), The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report. [ Links ]

EUROSTAT (2014). [ Links ]

GINEVIÈIUS, R.; HAUSMANN, T. & SCHAFI, S. (2007), “Seniorentourismus – Die zielgruppe senioren ingastgewerbe und touristik”. Business: Theory and Practice, 8(1), pp. [ Links ] 3-8.

HELPAGEINDIAPROGRAMME (2014), http://www.helpageindiaprogramme.org/Elderly%20Issues/problems_of_the_elderly/index.html. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE, G. (1980), “What is culture A reply to Baskerville accounting”. Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 28, Issues 7-8, October-November, pp. 811-13. [ Links ]

ICOMOS (2008), International Commission on Monuments and Sites. [ Links ]

INE (2014), Relatório da Receita Pessoa Física por Escalão. [ Links ]

PACKER, J. & BALLANTYNE, R. (2004), “Is educational leisure a contradiction in terms Exploring the synergy of education and entertainment”. Annals of Leisure Research, 7(1), pp. 54-71. [ Links ]

KOH, C.; JOSEPH, D. & ANG, S. (2010), “Cultural intelligence and global IT talent”. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The Handbook of Technology Management, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 828-844. [ Links ]

KOLB, D. A. (1984), Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, Prentice Hall PTR, Englewood Cliffs. [ Links ]

KORPAN, C. A.; BISANZ, G. L.; BOEHME, C. & LYNCH, M. A. (1997), “What did you learn outside of school today Using structured interviews to document home and community activities related to science and technology”. Science Education, 81, pp. 651-662. [ Links ]

LIVERMORE, D. (2008), “Culture intelligence and short-term missions: the phenomenon of the fifteen-year-old missionary”. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 271-285. [ Links ]

MASLOW, A. (1943), “A theory of human motivation”. Psychological Review, 50, pp. 370-396. [ Links ]

MCCABE, S. & JOHNSON, S. (2013), “The happiness factor in tourism subjective well-being and social tourism”. Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 41, April, pp. 42-65. [ Links ]

MINNAERT, L.; MAITLAND, R. & MILLER, G. (2009), “Tourism and social policy: the value of social tourism”. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), pp. 316-334. [ Links ]

NEVES, J. M. O. (2009), Estudo das Motivações Turísticas e do Comportamento em Turismo dos Seniores Portugueses no Mercado Interno: O Caso do INATEL e das Universidades Portuguesas da Terceira Idade. Fundação INATEL. [ Links ]

NG, K.-Y.; VAN DYNE, L. & ANG, S. (2009b), “Developing global leaders: the role of international experience and cultural intelligence”. In W. H. Mobley, M. Li and Y. Wang (Eds.), Advances in Global Leadership, Emerald Group, Bingley, pp. 225-250. [ Links ]

NG, K.-Y. & EARLEY, P. C. (2006), “Culture and intelligence: old constructs, new frontiers”. Group and Organization Management, 31, pp. 4-19. [ Links ]

NG, K.-Y.; VAN DYNE, L. & ANG, S. (2009a), “Beyond international experience: the strategic role of cultural intelligence for executive selection in IHRM”. In P. R. Sparrow (Ed.), Handbook of International Human Resource Management, John Wiley, West Sussex, pp. 97-113. [ Links ]

NIMROD, G. (2008), “Retirement and tourism – themes in retirees’ narratives”. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(4), pp. 859-878. [ Links ]

NIMROD, G. & ROTEM, A. (2010), “Between relaxation and excitement: activities and benefits in retirees”. Tourism International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(1), pp. 65-78. [ Links ]

ODDOU, G.; MARK, E.; MENDENHALL, M. E. & RITCHIE, B. J. (2000), “Leveraging travel as a tool for global leadership development”. Human Resource Management. 39(2-3), pp. 159-72. [ Links ]

STORY, J. (2010), Testing the Impact of Global Mindset on Positive Organizational Outcomes: A Multi-Level Analysis. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. [ Links ]

TAY, C.; WESTMAN, M. & CHIA, A. (2008), “Antecedents and consequences of cultural intelligence among short-term business travellers”. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications, M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 126-144. [ Links ]

TYLOR, E. B. (1871), “Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom”. www.books.google.com. [ Links ]

URIELY, N. (2005), “The tourist experience: conceptual developments”. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), pp. 199-216. [ Links ]

VAN DYNE, L.; ANG, S. & KOH, C. (2008), “Development and validation of the CQs: the cultural intelligence scale”. In S. Ang and L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 16-38. [ Links ]

VAN DYNE, L.; ANG, S. & LIVERMORE, D. (2010), “Cultural intelligence: a pathway for leading in a rapidly globalizing world”. In K. M. Hannum, B. McFeeters, and L. Booysen (Eds.), Leadership Across Differences. Pfeiffer, San Francisco, pp. 131-138. [ Links ]

VAN DYNE, L.; ANG, S. & NIELSEN, T. M. (2007), “Cultural Intelligence”. In S. Clegg and J. Bailey (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Organization Studies. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 345-350. [ Links ]

WOOD, E. D. & ST. PETERS, H. Y. Z. (2014), “Short-term cross-cultural study tours: impact on cultural intelligence”. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 25, Issue 4. [ Links ]

NOTES

[1] Agence Nationale pour les Chèques-Vacances (N. E.).

[2] Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales (N. E.).