Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.17 no.2 Porto dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.26300/v3dj-tv71

INSTITUTIONS AND RESEARCH

(Only) a glimpse of ancient history: knowledge production in portuguese universities (2010-2018)[1]

André Carneiro2

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0824-3301

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0824-3301

2 University of Évora, History Department, Portugal. Researcher at CHAIA-UÉ and CECH/FLUC. E-Mail: ampc@uevora.pt.

ABSTRACT

In this paper we overview the recent production of PhDs in the Portuguese university in Ancient History. Although the scarce number of data, we can detect trends and common realities, the most evident of all the severe impact of the economic crisis. Also, a more conventional approach in the themes is very manifest, meaning that the Portuguese research is less innovative that similar directions we can see in other countries. The combination of the effects means that Portuguese research in Ancient History is facing more difficulties in renewing its generations, in spite a more positive trend in most recent years.

Keywords: Ancient history; Knowledge production; Innovative research; Economic crisis

RESUMO

Neste artigo, apresentamos uma visão geral das teses defendidas recentemente nas universidades portuguesas no âmbito da História Antiga. Apesar do número escasso de dados, podemos detectar tendências e realidades comuns, com o impacto severo da crise económica em lugar de destaque. Além disso, manifesta-se de forma maios visível uma abordagem mais convencional nos temas, o que significa que a pesquisa portuguesa é menos inovadora das opções tomadas em outros países. A combinação destes dados significa que as pesquisas portuguesas em História Antiga enfrentam mais dificuldades em renovar suas gerações, apesar de se verificar uma tendência mais positiva nos últimos anos.

Palavras-chave: História antiga; Produção de conhecimento; Pesquisa inovadora; Crise económica

1. Context

Despite recent efforts, Ancient History still remains a marginal field of knowledge within the Portuguese academic and scientific system. The reasons for the relative unimportance attached to this subject are easy to understand and determine:

- The country’s peripheral position and large geographical distance from the territories studied;

- The fact that, historically, direct exchanges and connections with the leading cultural protagonists have been rare (despite the greater precision of recent research, resulting, above all, in more focused archaeological data);

- The widely recognized low level of investment in Portuguese research, meaning that there is no funding for the production of academic knowledge, further exacerbated by the difficulties in accessing the territories under study, due to the long distances involved;

- The troubled political scenarios currently existing in the Middle East, especially during the period in question (2010-2018), namely the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia, the wars in Syria, the never-ending conflict between Palestine and Israel, and, as main protagonists of havoc, terrorism and ISIS;

- The major financial crisis in Portugal, with the university and its research systems being hugely under-funded (the Troika intervention between 2010-2014 generated severe cuts in PhD grants), meaning that young researchers were primarily attracted to research fields with more direct access to the job market.

2. Numbers

As a result of the combination of these (and other) factors, it is not surprising to see that Ancient History is the research area that has produced the fewest completed PhD theses in the whole of the Portuguese academic system. In fact, of the 826 theses completed in eight disciplinary areas, we find that only 17 were from the field of Ancient History. As we shall see, even this number includes some theses related to other fields, which made use of Ancient History for comparative purposes or took it as their source of inspiration. In the end, this means that only 2.05% of Portuguese PhD theses can be allocated to the field of Ancient History, which is a tiny number. In fact, it is not sufficient even to ensure a regular renewal of researchers, so that, within the space of only a few years, this may well result in Ancient History becoming a complete desert in academic terms. This is a pessimistic, although realistic, perspective.

3. Rhythms

In this fragile scenario, it is logical for us to discover that the distribution of PhDs per year is minimal. This factor is particularly relevant if considered against the main economic backdrop in Portugal during the years under study. In fact, we can see that, between 2010 and 2013, only two PhDs were completed in Ancient History. The economic recovery has clearly gone hand in hand with a return to more regular research in this area, because in 2014, we had 3 PhDs, and 4 in each of the years 2015 and 2016, with a further 3, once more, in 2017. This is probably not just a simple coincidence, but, even so (as we saw earlier), this small universe is not enough to ensure a renewal of researchers.

4. Institutions

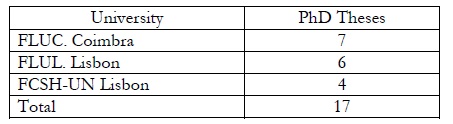

It is important to stress this particular feature, because, in Portugal, we already have very few specialists in Ancient History. In fact, it should further be noted that the geographical distribution of the universities offering PhDs in this area is heavily conditioned by the scattered location of researchers. This means that, of the 17 universities in Portugal, only 3 have hosted PhDs in Ancient History:

These numbers reflect the secondary role of Ancient History in Portuguese universities. These occasional PhDs are simultaneously both a cause and a consequence: they are closely linked with the scant human resources in this field of knowledge, and with the fact that universities have repeatedly removed Ancient History from many of their curricula. It is difficult to have specialists in this area and therefore teaching and the dissemination of knowledge have become more heavily concentrated in just a few institutions.

A simple comparison highlights the reduced scope of the Portuguese universe: at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid, a total of 28 PhDs were obtained in Ancient History between 2010 and 2016.

However, it is important to note that as many as 15 supervisors were involved in the 17 PhDs successfully presented in Portugal, which is an evident indication of diversity and vitality. Although these supervisors were concentrated in just three universities, it is important to stress this element, as it means that there are different perspectives and possibilities available for students.

When analyzed in closer detail, these statistics also reflect the international networks and collaborative links that the universities maintain with other partners. In fact, six of the PhDs that were completed involved students from other countries, highlighting the institutional associations and partnerships that existed at a broader level (particularly in Coimbra). This circumstance also emphasizes the limited human resources that we have internally, which is a structural problem that may endanger the future of Portuguese research in Ancient History.

5. Contents

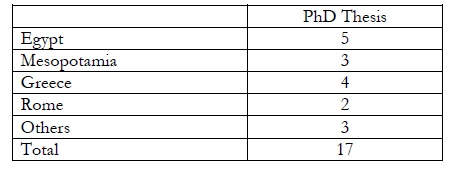

Traditionally, and because of its heterogeneity, Ancient History presents “hotspots” or contents that are more attractive to researchers: Egypt, Mesopotamia, and, because of their cultural customs and greater proximity, the classical civilizations-Greece and Rome. Not surprisingly, almost all of them have attracted the attention of PhD students:

Even the contents of “Others” are closely connected with “conventional” subjects, as they involve comparative perspectives linked to philosophical or literary details and analyzed from a contemporary viewpoint (perspectives of memory and fantasy; the idealization of cities compared with present-day Brasilia; and the underworld in ancient civilizations, comparing matters relating to Sumer and Rome-precisely the “conventional” subjects highlighted here).

Only one PhD was dedicated to the Iberian Peninsula. This involved a study of the Sertorian war, while all the others sought to examine internal aspects relating to the above-mentioned civilizations. In order to do this, the main emphasis was placed on literary evidence, sometimes relating to one single author (Euripides, Demosthenes, Hecataeus), one particular historical period (Amarna, Egyptian Middle Kingdom, Old Babylonian Period, neo-Assyrian Period) or just one specific element (sarcophagi or the tombs of royal officials, for example). Probably because of certain logistic constraints, no particular attention was paid to a specific geographical entity, for example, or to any kind of material culture (art, architecture, archaeological sites and finds, collections...). In some situations, the PhDs were more closely linked to other academic disciplines, such as Philosophy, Literature or Civil Law, than to History, since their focus was centered on this kind of analysis.

Due to the present-day research interests, we can see that intercultural or trans-temporal comparative viewpoints are chosen as a methodological tool or “pocketknife.” We can detect several examples of PhDs that have adopted this kind of contemporary perspective, creating frameworks to compare cultural contents in ancient literature (katabasis and anabasis), but especially ancient and present-day realities (the ancient concept of the city and modern-day Brasilia; ancient law codes compared to modern-day Brazilian legislation). Not surprisingly, these contemporary approaches are more frequently used by Brazilian researchers, since Portuguese students are used to following a more conventional methodological framework.

Seen from a certain perspective, these comparative studies account for most contemporary research. With the Mediterranean being regarded as the point of intersection of all kinds of political, social, and cultural experiences, Ancient History has become the ideal stage for finding new and innovative perspectives that can compare different time spans and geographical scenarios (see one of the latest examples in During; Stek, 2018). However, in recent PhDs, we can also notice a tendency to make anachronistic comparisons because they try to compare elements that belong to ancient civilizations with elements that characterize our present-day standards. This kind of perspective is especially notable among researchers from outside the European context, applying cross-cultural comparisons to spheres like Civil Law, cultural perceptions, or citizenship values.

6. Pathways

In recent years, Ancient History has undergone a dramatic change, especially due to archaeological findings that have brought entirely new perspectives about cultural interactions and social complexities in Hispanic communities. We can consider that the most recent overviews (for example, Armada; Grau-Mira, 2018) have established completely different paradigms when compared with those that were considered to be the standard at the end of the millennium. In Portugal, too, the improved methods of fieldwork, as well as recent archaeological findings, particularly in the south of the country (the Alqueva basin) have enabled us to paint a much more complex picture of the indigenous communities and, in particular, about their interactions with agents originating from outside the Mediterranean region. Thus, we now have a clearer understanding of the patterns of “connectivity” and “acceleration” (Horden; Purcell, 2000) in the Mediterranean world, which, in turn, has brought an entirely new perspective regarding Hispanic communities. These “variable geometries” in the indigenous patterns have been the subject of a rich and multifaceted research (for references, see Jímenez Diéz, 2010), enhancing the complexity of the situation. Moreover, multiple connections have recently been established between indigenous agents and external negotiators, particularly those who represented well-established political powers, highlighting the great wealth of strategic movements in action (see, for example, Celestino Perez; Lopez-Ruiz, 2016).

The PhDs considered here do not, however, follow this trend. The connections between the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean political agents are not visible. Also, no associations have been created between material culture and literary references or political history, in order to afford any greater depth to the analysis. Cross-cultural comparisons have been made, but only between past and present-day cultural values. Any kind of comparison between the Iberian Peninsula and the “Mediterranean circle,” or between centers versus peripheries, is completely avoided, therefore negating the possibility of confronting the wealth of available data with the literary evidence and the complexity of the cultural phenomena that marked the whole of the first millennium A.D. No doubt, this may represent a stimulating avenue for future research.

Interestingly, in the last few years, other major fields for debate have been ignored in the PhDs that we are considering here. For example, research in Ancient History has brought major contributions to questions like self-identity and cultural representations, or the duality of cultural topoi, with, on the one hand, the civilized and the friends being opposed to the hostile and the uncivilized. In this sense, the current debate has been centered on concepts such as cultural appropriation, globalization, self-representation, hybridization and Creolization, or on assimilations and exclusions, in which Ancient History constitutes a fertile terrain for discussion (see, for example, Sweeney, 2009). Since the 1990s, cultural clashes, influences, negotiations, or disputes between the different agents have offered ideal conditions for a rich and complex discussion, particularly in the context of the multivariate and destructured times in which we are now living. Seen from this perspective, even the complete absence of literary references about the “people without history” currently included in many post-colonial analyses (Gardner, 2013: 3-9) has been overcome, thanks to recent archaeological findings that have brought a greater cultural richness and complexity to the debate. But, in general, despite the specific nature of many references, this discussion is still far outside from the Portuguese academic world, where there is no evidence of these issues being analyzed or even confronted with the material evidence or literature.

Finally, the preference for examining “conventional” territories and societies means that all other cultures remain completely ignored, even some that might represent a promising and fertile terrain for further research. For instance, Carthage and all of North Africa-a territory with which Hispania had close links throughout Antiquity-are entirely absent from PhD dissertations. But so is the whole of the northern Mediterranean basin (except for the aforementioned Roman and Greek protagonists), which is completely lacking in research studies, such as, for example, the entire Balkan peninsula, the Mediterranean islands, and the pre-Roman cultures in the Italic region. There is also an absence of studies about entities that had close links with the Iberian Peninsula, such as the Phoenicians and other major Middle Eastern protagonists who depended on the help of mediators to trade with indigenous communities. We can also note the absence of biblical research, a vacuum that contradicts the Portuguese traditions in this area of investigation.

7. Perspectives

Finally, we reach the end with a certain sense of paradox. On the one hand, it would appear that Ancient History is a marginal and depopulated area of knowledge. There are only a limited number of PhDs, concentrated in just a few universities, working in the same traditional time frames, and concentrating on the same places. This may indeed constitute a “conventional” way of working, although some relevant and innovative perspectives have been fostered by Brazilian researchers. Seen from this perspective, there are some dark clouds hanging over the current scenario, as it would appear to be quite difficult to detect any signs of renewal, either in terms of human resources or in relation to the research paradigms.

On the other hand, as we have noticed, in recent years, it has been possible to detect a slight change in this trend. Numerically, more PhDs have been successfully completed, bringing more scholars into the research contingent. And, furthermore, it may well be that the complex and exciting new discoveries (in material culture) and perspectives (the way that we now look at and think about Ancient History) will bring a renewed approach to the study of this period. New tools for working and thinking are available and will now be used, giving rise to a refreshing debate and attracting new researchers. After all, looking back at the cultural and political richness of Ancient History is one of the best ways of perceiving and comprehending our troubled 21st century.

REFERENCES

Armada, X. and I. Grau-Mira (2018). “The Iberian Peninsula.” In Haselgrove, C., Rebay-Salisbury, K. and P. Wells (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age. [ Links ]

Celestino Perez, S. and C. Lopez-Ruiz (2016). Tartessos and the Phoenicians in Iberia. Oxford. [ Links ]

During, B. and T.D. Stek (2018). The Archaeology of Imperial landscapes. A comparative study of Empires in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean world. Cambridge. [ Links ]

Gardner, A. (2013). “Thinking about Roman Imperialism: postcolonialism, globalisation and Beyond?” Britannia, pp. 1-25. [ Links ]

Horden, P. and N. Purcell (2000). The corrupting sea. A study of Mediterranean history. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Jiménez Diéz, A. (2010). “Reproducing difference. Mimesis and colonialism in Roman Hispania.” In van Dommelen, P. and A. Knapp (eds.), Material connections in ancient Mediterranean. Mobility, materiality and identity. London & New York, pp. 38-63. [ Links ]

Sweeney, N. M. (2009). “Beyond ethnicity: the overlooked diversity of group identities.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology. Sheffield. 22: 1, pp. 101-126. [ Links ]

Received for publication: 03 September 2019. Recebido para publicação: 03 de Setembro de 2019

Accepted in revised form: 20 October 2019. Aceite após revisão: 20 de Outubro de 2019

[1] With an accompanying annex on pages 165-174 prepared by the editors of e-JPH with the assistance of Elsa Lorga Vila (Graduate of University of Evora; Master’s Degree in History-Nova University of Lisbon).

Annex:

Ancient History

PhD Theses in Portuguese Universities (2010-2018)

Prepared by the editors of e-JPH with the assistance of Elsa Lorga Vila (Graduate of University of Evora; Master’s Degree in History-Nova University of Lisbon)