Affective Geographies and Research

Subjectivity in the use of spaces and their representations has been an important object of study across the spectrum of human sciences, particularly in relation to the areas of human geography and social psychology. Deep maps are a clear example of such research, as they are drawn based on the perception, use, attributed meaning, and value that are ascribed to different geographical spaces.2 Such maps may relate to the fieldwork and discourses developed in relation to local, regional, and national identities. Regionalisms, nationalisms, and patriotisms make use of these representations, reconstructing them and giving them a material expression, which, all too often, is translated into aggressive action. At the other end of the humanities spectrum, literary imagery has spawned a broad range of studies, particularly in comparative literature,3 thus making this issue central to a number of areas of knowledge.4

In a 2001 article, João Leal sought to identify images of the Mediterranean South in the work of such leading Portuguese authors as the geographer Orlando Ribeiro and the anthropologists Jorge Dias and José Cutileiro (Leal, 2001:141-63). In doing so, he considered these authors’ views on the relationship between rurality and national identity, and the pastoral or counter-pastoral nature of their texts, depending on whether they depicted the countryside as a repository of beauty and harmony, and using Raymond Williams as their main theoretical anchor point.5 Orlando Ribeiro, Jorge Dias, and José Cutileiro analyzed specific issues in areas that formed reference spaces for which they constructed images that engaged with different affective geographical ties.

In his 1945 book Portugal, o Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico, Orlando Ribeiro, who was influenced by French human geography, proposed dividing mainland Portugal into three areas: Norte Atlântico (Atlantic North), Norte Transmontano (Inland North) and Sul Mediterrânico (Mediterranean South). This demarcation was accepted and has since inspired decades of research in the social sciences, in areas ranging from material culture to agrarian history, and even in linguistics and architecture. In this seminal work, as well as other studies, the geographer states that, whereas the Portuguese state spread from the north to the south of the country, civilization spread from the south to the north, as exemplified by the Romans, the Arabs, and the vibrancy of southern medieval urban life, clearly in thrall to the Mediterranean world (Ribeiro, 1945; 1961; 1968; 1977).

Jorge Dias, who studied in Germany, is another case in point. He researched material culture in Portugal, particularly the spread of agrarian technologies across the country (as did Ernesto Veiga de Oliveira, Benjamim Pereira, and Fernando Galhano). In the case of ploughs, for example, he proposed the same regional divisions as Orlando Ribeiro: the Atlantic North, with its quadrangular plough and cornfields; the Inland North, with its radial plough and rye fields; and the Mediterranean South, with its sole ard plough and wheatfields. He also researched local communities and national identity. Focusing on the north, he was deeply interested in the remaining traces of communitarianism, its Lusitanian and Suevi origins, and such constructions as granaries (Dias, 1948; 1948a; 1953; 1961; Dias, Oliveira, and Galhano, 1963).

José Cutileiro, a social anthropologist trained in the British anthropological tradition, concentrated his research in the Mediterranean South of Portugal. In Ricos e Pobres no Alentejo, he studied the Alentejo prior to the revolution of April 25 1974, an area that was riven by social asymmetries, patronage and clientelism, and dominated by rural landowners with links to the political power of the Estado Novo regime, against whom the poor and subjugated rural workers waged their own bitter struggle. Somehow, this repulsive social space ended up characterizing the geographical area in which it lay, to which the author became resistant (Cutileiro, 1977 [English edition: 1971]).

For João Leal, therefore, the discourses of Jorge Dias and Orlando Ribeiro, who showed empathy for the North and the Mediterranean South respectively, are pastoral, whilst José Cutileiro’s book is counter-pastoral.

João Leal’s article may suggest other works, but I decided to undertake an exercise based on the work of Michel Giacometti. Moreover, instead of focusing on the relationship between rurality and national identity or on the question of pastoral and counter-pastoral discourses, as raised by Raymond Williams, I concentrated on the issues of the weighting, the role, and the configuration of spaces. In this article, I took previously known aspects of the work of this Corsican ethnographer as the starting point for an inquiry into the places and spaces covered by his research. Through both quantitative and qualitative analysis, my aim is to assess the geographical coverage of his action, indicate his characterization of the regions considered, and identify those that originated specific recordings, as well as observe the dedications, the support networks that he mentioned, and the support that he sought. In short, my intention is to characterize a geography of Giacometti's practices and emotions.

Giacometti’s Journey

A key figure in Portuguese ethnomusicology, Michel Giacometti (Ajaccio/Corsica, 1929-Faro, 1990) broadened his research scope to cover other aspects of Portuguese popular culture.6 Giacometti came to Portugal in 1958, and, from then until his death in 1990, his Portuguese journey consisted of several phases.

In the first phase, which lasted until April 25, 1974, he focused on collecting traditional music, oral literature, musical instruments, and folk art. Having set up the Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses (Portuguese Sound Archives) in 1959, he produced numerous recordings with the musicologist Fernando Lopes Graça, including the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa (Anthology of Portuguese Regional Music) released between 1960 and 1970, which are considered seminal works in this area. Thereafter, like Fernando Lopes Graça, Giacometti was regarded as a member of the PCP (Partido Comunista Português [Portuguese Communist Party]) or as a “compagnon de route.” In his work, he paid a great deal of attention to the media, particularly radio and television, and became well known for a television series called Povo que Canta (People who Sing), which was broadcast on RTP, the Portuguese national television network, between 1970 and 1974.

The following phase was one of hope. During the revolutionary period, when Giacometti made a number of one-off collections, he became involved in a much larger initiative. He coordinated the Plano Trabalho e Cultura (Work and Culture Plan, 1975), which was implemented by 124 students from the Serviço Cívico Estudantil (Student Civic Service). He combined the collections that he made through this plan with his new responsibilities at INATEL (Instituto Nacional para o Aproveitamento dos Tempos Livres dos Trabalhadores [National Institute for Workers’ Leisure Time], where he designed the Centro de Documentação Operário-Camponesa-Museu do Trabalho (Worker-Peasant Documentation Centre-Museum of Labor). The collections that he made during this phase contributed to the main thrust of his previous work while also expanding into the area of material culture. He assembled data on traditional medicine and public health as well as new forms of public expression, which included a particular interest in muralism. He also broadened his recording practices to cover the organized labor movement and the political and social initiatives of the time. As he had done before, he also sought to document his ethnographic collections through the medium of television. Underlining his concern with institutionalizing his collections, the founding deed for the Centro de Documentação Operário-Camponesa-Museu do Trabalho was signed in the Portuguese city of Setúbal in 1975.

In the third phase of his life, which began when he left INATEL in 1976, Giacometti reused some of his older materials, collected some new materials, organized occasional exhibitions, and returned to radio broadcasting. This period was notable for the 1981 publication of the Cancioneiro Popular Português (Portuguese Popular Songbook), once again compiled in collaboration with Fernando Lopes Graça. However, the main focus of his work was the safeguarding and institutionalization of his ethnographic collections and the other material he had gathered. To this end, he joined forces with the Centro de Tradições Populares Portuguesas (Centre for Portuguese Popular Traditions) at the Faculdade de Letras-Universidade de Lisboa (School of Arts and Humanities-University of Lisbon), whose oral literature publications included some of the collections that Giacometti himself had organized or compiled. Following protracted negotiations, he sold part of his musical collection to the Secretaria de Estado da Cultura (Portuguese State Department for Culture), with the aim of establishing an Instituto de Etnomusicologia (Institute of Ethnomusicology), but still retained the right to make use of the material himself. He also sold his folk art collection and musical instruments as well as his library, to the Câmara Municipal de Cascais (Cascais Municipal Council) in 1981 and 1989, respectively. These were all sent to the Casa Verdades de Faria-Museu da Música Regional Portuguesa (Verdades de Faria House-Museum of Portuguese Regional Music). Giacometti sat on the museum’s steering committee from 1988 onwards. In 1987, he had also taken part in the exhibition presenting the Museu do Trabalho (Museum of Labor) project in Setubal.

In summary, while in Portugal, Michel Giacometti collected ethnographic material, published recordings, and was involved in broadcasting. He also worked to set up a sound archive and the Centro de Documentação Operário-Camponesa-Museu do Trabalho. I may eventually unearth other aspects and results of his work, such as those that came to light in 2009 and 2010/11 (Ramalhete and Júdice, 2009; Almeida, Guimarães, and Magalhães, 2009; Giacometti, 2010/11). The aim here, however, is to analyze the work published in his lifetime, his multifaceted ethnographic involvement, and his wish to safeguard materials in both their spatial and affective dimensions.

Mapping Michel Giacometti’s Work

Giacometti worked in many different parts of the Portuguese mainland, as evidenced by his published musical works, his songbook, his television series, and his 1975 initiative. Although some of his collected material is yet to be published or studied, the main works published during his lifetime, and those that emerged later on, clearly underline the national dimension of his work. Here, I take a closer look at the geographical setting of the areas into which he researched.

In order to map the geographical coverage of his published work on the rural world during all the phases of his life, I first established a database, with 254 entries, of the locations of the musical pieces that he collected. These entries had to satisfy two conditions: i) they had already been published in works designed to document Portugal’s “musical nation”; and ii) they were clearly identified.

In more detail, my sources were: five albums from the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa (Anthology of Portuguese Regional Music) (1960, 1961, 1963, 1965, 1970); six albums from the Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa (Small Anthology of Portuguese Regional Music) (1971); the album Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses (Traditional Portuguese Religious Songs) (1971); the cassette Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português (Work Songs and Rhythms of the Portuguese People) (1983); and the Cancioneiro Popular Português (Portuguese Popular Songbook) (1981). I did not include the French or English editions, which are identical to the Portuguese, nor any republications or second editions.

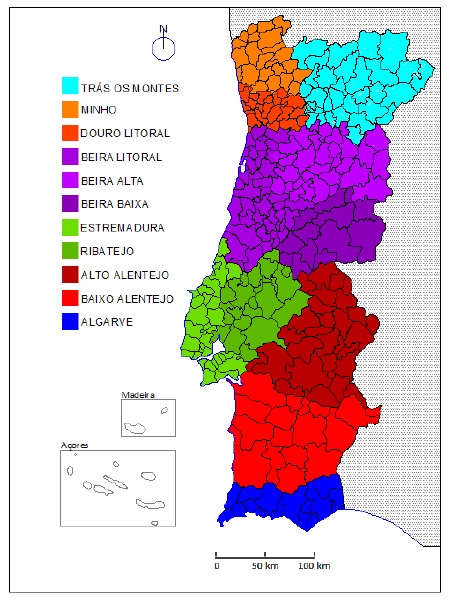

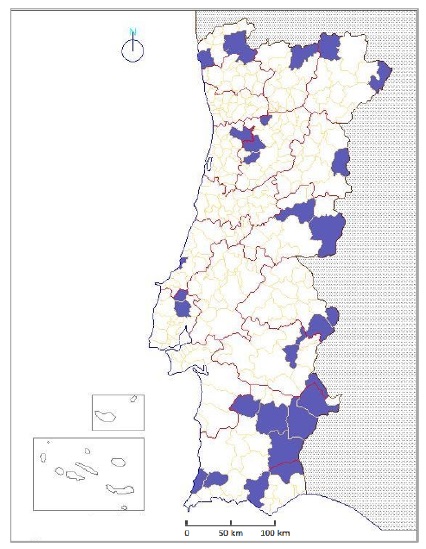

I applied the various spatial categories used by the Corsican ethnographer to my database (province, district, municipality, parish, and locality). Records were grouped together on a regional basis. The regions established for mainland Portugal are roughly the same as those used by Giacometti for the albums comprising his Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa and the Plano Trabalho e Cultura: Minho, Trás-os-Montes, Beira, Estremadura, Alentejo and Algarve (Figure 1). In this material, Minho extends down to Douro Litoral, Ribatejo is linked to Estremadura, and Beira is considered as one single region.

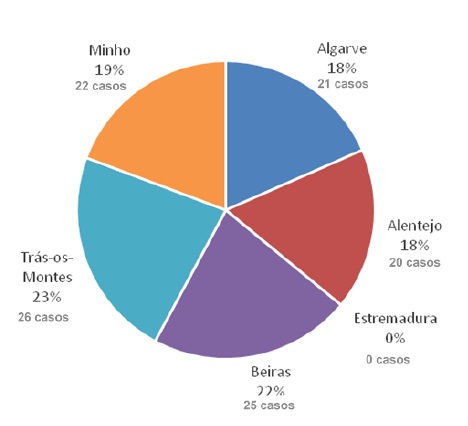

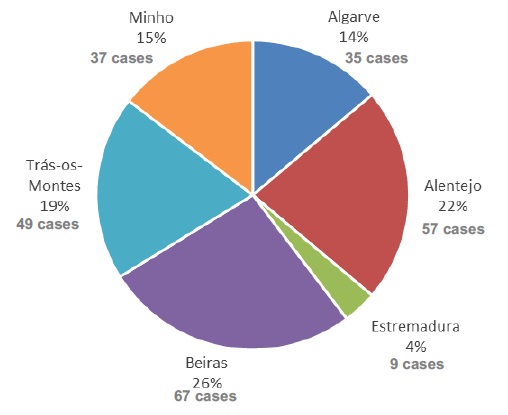

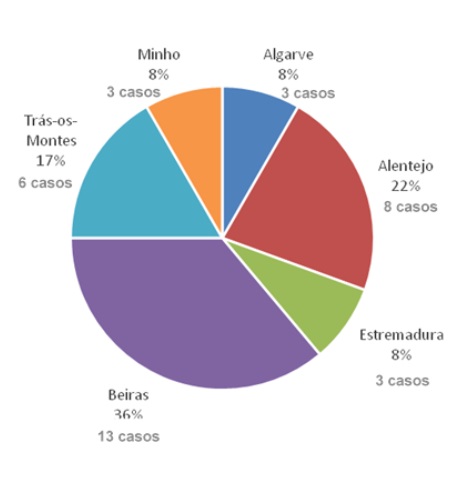

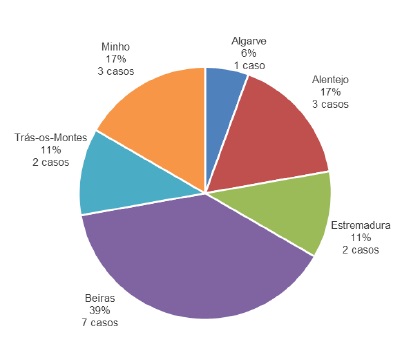

I may thus analyze the regional distribution of all the musical recordings from the aforementioned works (Figure 2). All the regions into which Giacometti divided the country (Minho, Trás-os-Montes, Beira, Estremadura, Alentejo and Algarve) are featured. Estremadura appears to be underrepresented, most likely because the corresponding Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa for the region was never released. Beira, Alentejo, and Trás-os-Montes are particularly well represented.

Fig. 2: Regional distribution of the musical recordings in Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses, Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português and Cancioneiro Popular Português

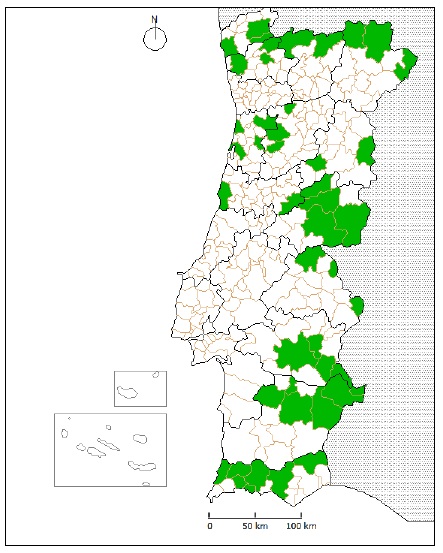

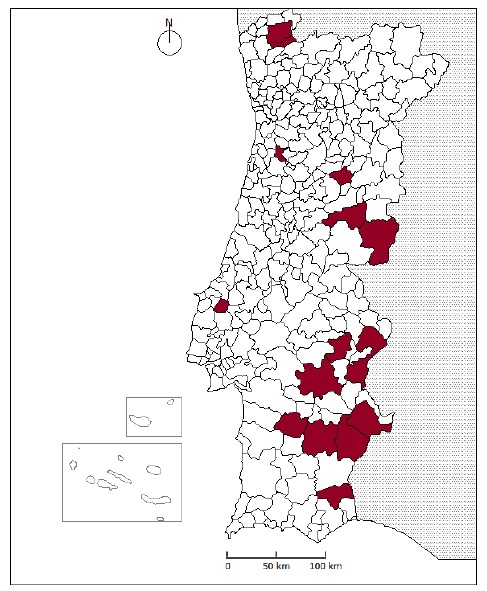

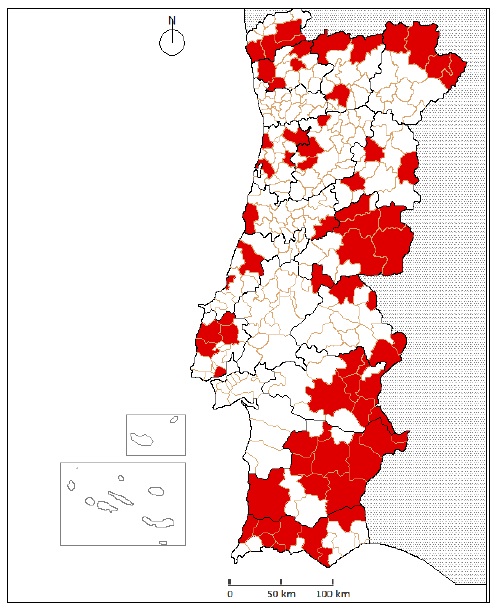

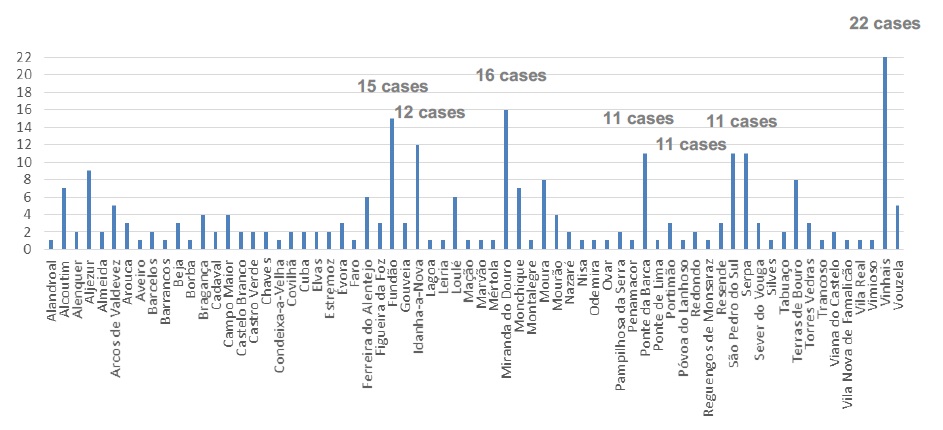

A smaller-scale map (Figure 3) and a graph (Figure 4) show the municipalities from which these musical pieces were drawn. The map (Figure 3) reveals a greater proportion of municipalities in inland areas, particularly along the northern border and in the Beira Baixa, Alentejo, and Algarve regions. The municipalities of Vinhais and Miranda do Douro (Trás-os-Montes), Fundão, Idanha-a-Nova and São Pedro do Sul (Beira), Ponte da Barca (Minho), and Serpa (Alentejo) were significant sources of material that was included in the published musical collections (Figure 4).

Fig. 3: Municipalities represented in Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses, Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português and Cancioneiro Popular Português

Fig. 4: Municipal distribution of the musical recordings in Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses, Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português and Cancioneiro Popular Português

After this general overview, I now consider the different geographical incidences in the various phases of Giacometti’s journey.

Let us look at the first phase of his time in Portugal.

I begin with the musical recordings in the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, released between 1960 and 1970 (114 cases), and the Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa (36 cases), released in 1971. These anthologies were supposed to cover the whole country although there was no anthology released for Estremadura in the first series.

Fig. 7: Regional distribution of the musical recordings in Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa

As was to be expected from the graphs (Figures 2 and 4) and the map (Figure 3) of all 254 cases (of which these form a substantial part), the inland areas were particularly important, namely the northern border, the Alentejo, and, above all, Beira Baixa (Figures 5 to 6,7,8).

A detailed analysis of the musical recordings in the other nationwide album released during this phase (Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses, 1971) reveals the continuing preponderance of Beira Baixa and, above all, the Alentejo (Figures 9 and 10).

Fig. 9: Regional distribution of the musical recordings in Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses

I now move on to another of Giacometti’s works, in a different format and requiring a different analytical approach. The television series Povo que Canta, directed by Alfredo Tropa, was broadcast between 1970 and 1974. The subtitle for this documentary series (Vozes e Imagens para uma Antologia da Música Popular Portuguesa [Voices and Images for an Anthology of Portuguese Popular Music] emphasized the fact that the programs contained not just audio but also visual recordings. As such, there are no grounds for including these latter recordings in the database and undertaking an exercise similar to the one that was applied to the purely musical recordings. In the television series, these recordings are not always individualized and they intersect with items of oral literature and even interviews. I may, however, consider the various municipalities that appeared in episodes of Povo que Canta.

As there were both regional and thematic programs (covering several regions in a single episode), and although the path taken was not a linear one, it appears that the team led by Michel Giacometti and Alfredo Tropa started by following an inland route that ran from south to north. After this, the ethnographer and the RTP team planned to move on to the coastal region and the islands. However, the project was interrupted by the 1974 revolution, and the last (pre-recorded) program was broadcast after April 25 of that year.

The route was similar to the one followed in 1972 by António Pintado and Eduardo Barrenechea, which formed the starting point for the book A Raia de Portugal. A Fronteira do Subdesenvolvimento (The Portuguese Borderlands. Frontier of Underdevelopment). Giacometti and the Spanish authors shared the same drive to document, disseminate, and denounce the poor living conditions of the people in the border areas and, by contextualizing these conditions, the political power that had allowed this situation to develop.7 It is not by chance that the book begins with a description of Las Hurdes-which is, in fact, located directly across the border from the inland Beira region. At various points, the authors return to the situation in Las Hurdes, construing the poverty and isolation of the region as a paradigm for the backwardness of the border area. The symbolic weight of the extreme misery of Las Hurdes, in the province of Cáceres, revealed in a raw Luís Buñuel documentary in 1932, is evident in the book. The same poor rurality is unveiled by those producing the sounds and images, transmitted through modern technology, for the Povo que Canta series.

The map of Portuguese municipalities covered by the television series Povo que Canta (Figure 11) emphasizes the importance of the underdeveloped hinterland as a recording space, most particularly the northeastern Trás-os-Montes border area, Beira Baixa, the Alentejo and the Algarve. However, these findings should not be overstated, as the television series remained unfinished.

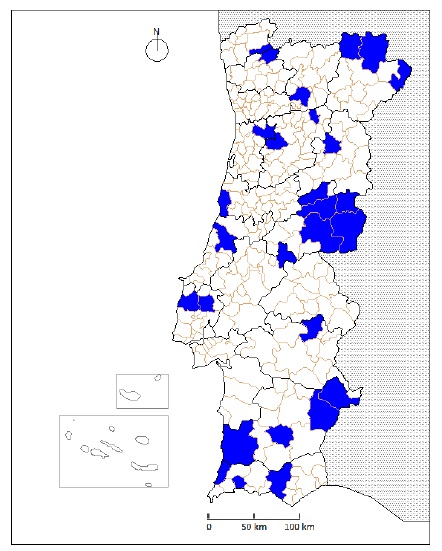

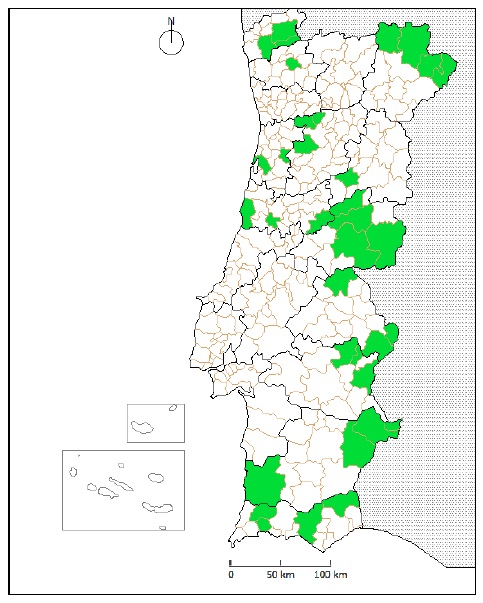

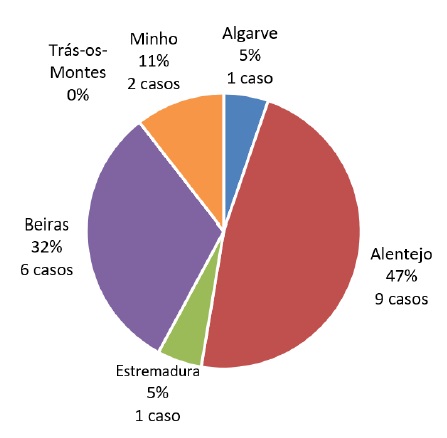

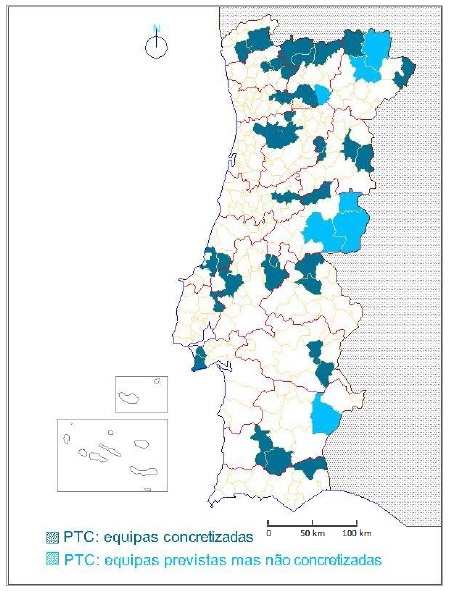

I now turn to the second phase of Giacometti’s time in Portugal. I wish to analyze the geographical scope of the 1975 Plano Trabalho e Cultura. There is no justification for including the oral recordings (or the artefacts or surveys) in the database, as the results of these are scattered and, in many cases, have yet to be identified or published. Instead, I looked at the way the teams were distributed across the country (Figure 12).

Fig. 12: Municipalities assigned to the planned and the actual Plano Trabalho e Cultura (“Work and Culture Plan”) teams.

As this plan was the most substantial collection initiative undertaken by Michel Giacometti after the April 25 revolution, the geography of the teams is significant, particularly if cross-referenced with their number and the context in which they were formed.

The Plano Trabalho e Cultura planned for 38 teams to be distributed as follows: eleven in Trás-os-Montes; nine in Minho; eight in Beira; five in Estremadura; four in the Alentejo; and one in the Algarve. In fact, only 31 teams went into the field, some were disbanded, and one extra team was formed. Thus, the results of this plan were produced by a total of 32 teams.

The project leader did not pay too much attention to covering the south of the country when he drew up the Plano Trabalho e Cultura. Under the plan, only five teams were supposed to go to the Alentejo and the Algarve and only three actually did so. This may have been because the students who signed up for the teams were not very interested in going to the south or because Giacometti did little to encourage the formation of teams for this part of the country. However, it proved easy to set up or reconstitute groups for the south; in fact, the only team formed once the initiative was underway was set up in this area. All the existing teams in the area received new members from groups that had been disbanded in the north. There was a clear trend of students transferring from the north to the south.

Not only was the south not a major target area for the Plano Trabalho e Cultura, but also, in the case of the politically left-leaning Alentejo, the few municipalities covered were ones that were less closely linked with the PCP. The southern teams formed at the start of the Plano Trabalho e Cultura worked in municipalities in which the PCP had its lowest vote count in each district. The team formed later was the only one to work in a municipality where the PCP had garnered more votes, even though this was still one of the least communist-oriented areas in the district.8

It is important to understand the targeting of the north, compared to a non-priority south that did, however, become the place in which to seek refuge. Probably, the urgent need to intervene felt by Giacometti and those around him led to teams being dispatched to the northern lands of “obscurantism.” However, the first draft of the Plano Trabalho e Cultura was drawn up prior to the first democratic elections (so the precise electoral geography of the country would not have been known at that time). Furthermore, in the southern regions, the Algarve, where the PS (Partido Socialista [Socialist Party]) won, received the least coverage.

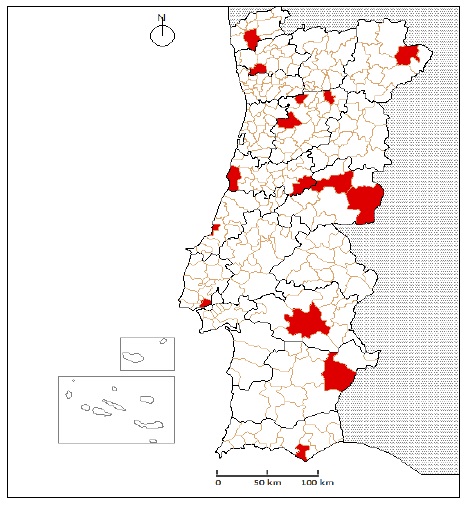

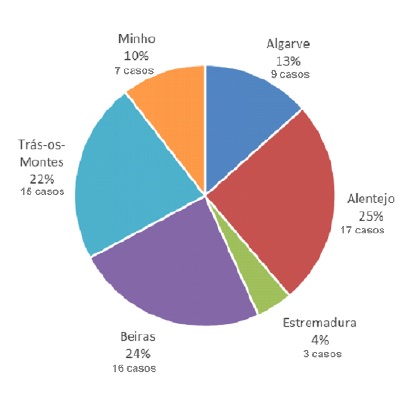

Moving on to the third phase of Giacometti’s time in Portugal, I come to the Cancioneiro Popular Português, published in 1981 (Figures 11 and 12). This work, which was designed to cover the whole of mainland Portugal and the islands, contains musical recordings collected over many decades by Giacometti and Lopes Graça, among other researchers. Although all the Corsican ethnographer’s collections were made prior to April 25 1974 (i.e., they date back to the first phase of his life in Portugal), their publication in this book may reveal what Giacometti wanted to show in 1981 by embedding them in a much wider set of recordings.

The pieces that were recorded by Giacometti on his own (67 cases) nearly all came from inland areas, namely the Alentejo, Beira, and Trás-os-Montes. The Alentejo is particularly prominent on the municipalities map.

Fig. 13: Regional distribution of the musical recordings collected by Giacometti and published in the Cancioneiro Popular Português

Fig. 14: Municipalities where Giacometti collected musical recordings and published them in the Cancioneiro Popular Português

Work songs from the Beira region are the predominant feature of a 1983 cassette, Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português (Figures 15 and 16), which also recycled several recordings.

Fig. 15: Regional distribution of the musical recordings in Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português

The materials show that Giacometti planned to cover the whole country, albeit unevenly, and this justifies my analysis at the municipality level. The specific focuses varied over the different phases in his life.

In this geographical approach to Michel Giacometti's work, it seems appropriate to consider other qualitative indicators relating to the way he concentrated on certain regions. This may be achieved through an analysis of his writings and programs, as well as his practices.

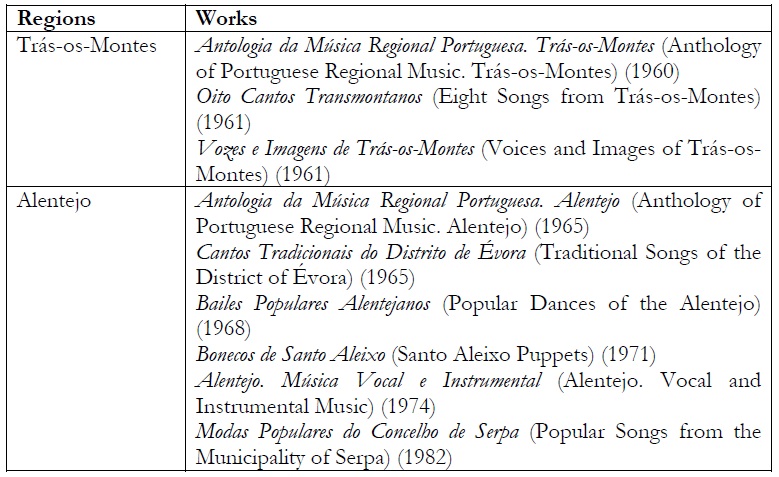

One way of gauging Giacometti’s dedication to the regions of Portugal is to look at his single-region publications. Nine albums and cassettes fall into this category.9 These recordings pertain specifically to Trás-os-Montes, but, above all, to the Alentejo (Table 1).

Whichever region he is dealing with, it is generally the case that Giacometti casts an affable eye over and conveys an epic vision of the lives of those he refers to as “our people,” explaining their suffering and referring to emigration. The concept of “our people” is anchored in the countryside and fishing communities. It is certain that the Plano Trabalho e Cultura was designed to serve a Centro de Documentação Operário-Camponesa - Museu do Trabalho (Worker-Peasant Documentation Centre - Museum of Labor), which, as the name implies, includes a factory worker component. It is also safe to say that in radio programs and even in the Cancioneiro Popular Português, Giacometti sought to pay heed to urban voices. However, such collections are in the minority and have not yet been published. The only one of his albums to show any traces of his attention to the urban lower classes is Fados (1960). Such references in his writings are restricted to a few pages of collections made by other ethnographers in the Cancioneiro Popular Português (1981).

This empathy with “our people” is reflected in the covers and texts of the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. In the first album in this series, on Trás-os-Montes, the region that he visited when he first came to the country, Giacometti is shocked by “the lines of a landscape as brutal as an accident that engrave the dry and barren weathering that the faces bear and the songs evince.” In fact, he follows Kurt Schindler in classifying this as “pure gold.” In the Minho, he encounters the “daily saga” of the rural and artisanal world and notices the countrywomen with faces like “medals minted in the metal of a harsh life.” In Beira, he thanks its people. Further south, he acknowledges the people of the Alentejo. Finally, he emphasizes the isolation of the Algarvian hills, which persists despite the changes of the 1960s, as well as the “daily courage” of the fisherfolk.

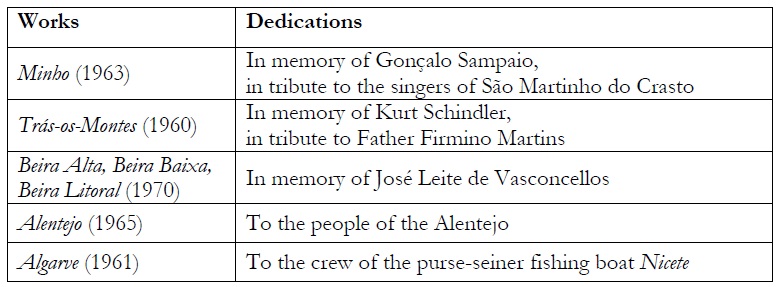

The dedications of his works represented a place for invocations, affiliations, and recognitions, while serving to express a sense of complicity and affection. All the albums in the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa have explicit dedications (Table 2).

The albums about the Minho, Trás-os-Montes and Beiras are dedicated to the memory of researchers. The first of these is also dedicated to singers. In the case of the Algarve, Giacometti “fraternally” dedicates the album to a collective entity, the crew of a vessel whose toils he accompanied on a deep-sea fishing trip. He goes on to say: “this album is respectfully dedicated, in a spirit of fraternal friendship, to these rugged men, their work and their daily courage.” The album Alentejo is dedicated to a much larger collective body: the “people of the Alentejo.” This mention of the “people of the Alentejo,” accompanied by texts that extol the value of the workers, their work, and their singing, allows us to deduce a specific use of the concept of “people”: not as a regional collective but as the lower classes. Thus, it comprises a signal, an intertextual message, a tribute.

The few dedications that were made in the television series Povo que Canta are short. Appearing here and there, they are addressed to a collective (Sociedade de Instrução Tavaredense [Educational Society of Tavarede], Figueira da Foz), some inhabitants, and the researchers mentioned above, namely Father Firmino Martins and Gonçalo Sampaio. There are also some first-time mentions for José António Guerreiro Gáscon, Virgílio Pereira, and Ernesto Veiga de Oliveira.

I now turn to the support structures that Giacometti benefitted from and wished to recognize. In ethnographic work, the informant network is a key support structure. In the case of Giacometti’s cultural militancy, this support network was of even greater importance. The network enabled the establishment of contacts for a social and political intervention project that, prior to April 25, 1974, involved the dissemination of news, training, politicization, and support in the event of difficulties. No less important was the fact that the network offered comforting and reinvigorating opportunities to socialize.

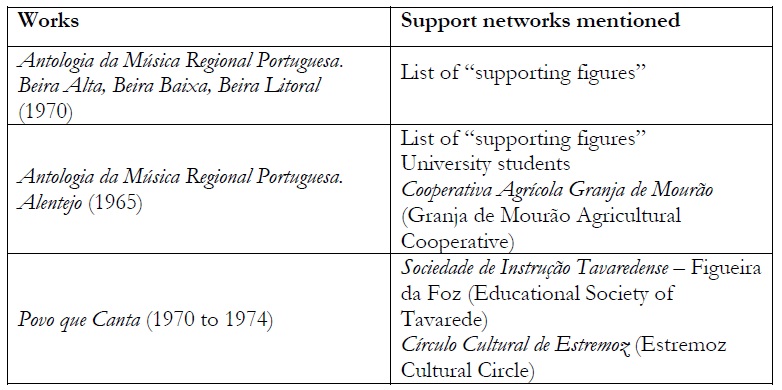

All the evidence points to the importance that the support networks had for Giacometti’s collection work. His published works make this clear (Table 3).

Table 3 Support networks named on albums from the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa and in episodes of Povo que Canta

On the Beiras and the Alentejo albums from the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, the Corsican ethnographer offers lists of “supporting figures.” On the Alentejo album, Giacometti mentions an ethnographic questionnaire administered in collaboration with university students and an agricultural cooperative (Granja do Mourão, 1963)-a one-off case. In the television series Povo que Canta, Giacometti refers to the support given by two collectives: in Beira, the Sociedade de Instrução Tavaredense, and in the Alentejo, the Círculo Cultural de Estremoz. The latter is mentioned in episodes dealing with the popular theater of the Bonecos de Santo Aleixo, of which he published recordings. Giacometti also worked with people who are named collectively, such as the “group of collaborators in Alenquer,” whose collections were used by Aliete Galhoz in the works of oral literature that she coordinated. She herself was also a long-time collaborator of the Corsican ethnographer (Galhoz, 1988:609-12).

Having benefitted from those supports in the 1960s/1970s in the Beira and the Alentejo, in the 1980s, Giacometti presented new collection and publishing proposals to the municipal councils of the latter region. The councils he targeted were Serpa, Cuba, Alvito, and Alcácer do Sal. In the wider Alentejo region (which, for Giacometti, started in Setúbal), local bodies organized exhibitions of the material culture objects from the Plano Trabalho e Cultura, both in Setúbal, the city chosen to house the Centro de Documentação Operário-Camponesa - Museu do Trabalho, and in Grândola. Giacometti was involved in Setúbal’s hosting of an inaugural exhibition designed to showcase the vocation of the Museu do Trabalho10 as the museum did not yet have a permanent home of its own.

Giacometti also sought support from central authorities (like the Portuguese State Department for Culture), a research center at the University of Lisbon, and the Cascais Municipal Council, in the town where he lived.

However, during this phase, Giacometti spent most of his time engaging with the wider Alentejo. In 1982, he took part in local elections in Ourique, supported by the PCP-led coalition, and made use of his ethnographic collections during the election campaign (Giacometti 2010/11, vol. 12). After the revolution, the wider Alentejo cemented its position, in Giacometti’s view, as a shelter, a stronghold to be maintained, a space to be expanded.

Before I finish, I should consider Giacometti’s views of different regions in terms of their folk polyphony, which he saw as the “dominant feature” of our musical folklore.11 It should be stressed from the outset that this view of folk polyphony had consequences for the way in which I see popular culture and the people. This was intended to serve as the creator and interpreter of an elaborate type of music such as polyphony, which would thus no longer be linked only to high culture (Medeiros, 2017).

In the Povo que Canta television programs, broadcast in the 1970s, Giacometti showed us how he saw the Alentejo. He pointed out that male polyphonies expressed the fraternalism of work and difficult lives: “an expression that is always severe, near dramatic […] of the fraternal need of those that toil, side by side, on collective tasks.”12 He emphasized the fact that the songs conveyed social inequalities and protest. He reported on the scant religious engagement of a people that, nevertheless, sang the Menino (Child) born in poverty.13 More specifically:

Baixo Alentejo, not much given to religious singing, is perhaps one of the most prodigal regions in the country when it comes to songs alluding to the birth of the Child. The man from the south of the Alentejo, for reasons that may well be rooted in his social and economic condition, sings songs whose harsh lines do not prevent the expression of a certain tenderness towards the Child, born in such poor rags.14

In keeping with this sensitivity, practically half of the recordings on the album Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses were sourced from the Alentejo, as I have already seen.

In 1984, Giacometti reiterated his description and interpretation of the cante, the polyphonies in the Alentejo:

The continuing expansion of cante and its adoption by part of the rural and urban proletariat (curiously, not all of whom are to be found in the Alentejo) may be attributed to the fact that it is seen as a wellspring form, that is, as a collective and gregarious song that is entirely suited to the expression of ideas and feelings of belonging to the common heritage. Moreover, for a long time, cante, rarely absent from the arena of peasant struggle, symbolized-at least in the spirit of the rural peoples living south of the River Tagus-the solidarity of the poor in the fight for their basic rights (Giacometti 2010/11: Volume 11:14-15).

In a 1972 program on folk polyphony, Giacometti draws a distinction between the polyphonies of Beira Alta and those of Baixo Alentejo. Comparing the regions, using, respectively, examples from the districts of Viseu and Beja, Giacometti notes that “the lyrics of the choral songs of the Alentejo are regularly updated to reflect-perhaps more so than in any other region of the country-the problems, tensions and social situations of the time.”15 Giacometti has a different interpretation for the female polyphonies of Beira Alta, and he even contrasts these with the male polyphonies of the Alentejo:

[If there is a] tendency on the part of the people of the Alentejo to express, through cante, those problems that currently determine their social life, in the singing of Beira Alta this does not generally happen: the lyrics seem to be reshaped through a slow process of assimilation rather than through improvisation or adaptations to the contemporary environment. This is why the themes are largely ceremonial or merely lyrical in nature.16

In his approach to the Alentejo and Beira Alta, Giacometti differentiates between singing practices, by emphasizing their various social contexts, with their different social structures and tensions. It is clear that his affinities lay mainly in the Alentejo.

Conclusions

It should be noted that Giacometti’s published, released, or broadcast works primarily date from before the revolution of April 25, 1974 or are based on collections made before this.

I may draw a number of conclusions from my quantitative and qualitative analysis of the musical recordings of the Cancioneiro Popular Português, Povo que Canta and the Plano Trabalho e Cultura.17 Although Giacometti’s work covers the whole of mainland Portugal, not every region is equally represented. There is more coverage of the northeastern inland areas of Trás-os-Montes, Beira Baixa, and the Alentejo.

Over time, the level of attention that Giacometti gave to different areas underwent several changes.

Giacometti started his work in Portugal in Trás-os-Montes: inspired by Kurt Schindler, and in contact with French museums, he revered the region’s strength and wanted to record its music and its orality. In the first phase of his time in Portugal, he dedicated several recordings to the region and returned to it in the early 1980s. His work in the region mainly focused on the northeastern borderlands (Vinhais, Bragança, Vimioso, and Miranda do Douro).

Like Las Hurdes, Beira Baixa signified interiority and underdevelopment, and shared some traits with the Alentejo. Giacometti received extensive support whilst in Beira Baixa, particularly through the contacts network of the Jornal do Fundão, a weekly newspaper that was closely linked to the opposition to the Estado Novo. Many of his texts and album covers were produced on the newspaper’s building, including the records in the Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa, with their emblematic covers that caused them to be known, even to this day, as the “discos de serapilheira” (the burlap albums). He paid a great deal of attention to both this municipality and the neighboring Idanha-a-Nova, whose agricultural structures partly resembled those of the Alentejo. Although Beira Baixa was important in his first and second phase, Giacometti’s later research did not focus on this region.

In fact, over time, he became more closely involved with the Alentejo. He traveled and conducted research in such municipalities as Ferreira do Alentejo, Évora, Moura, and Serpa, amongst many others. Moreover, the Alentejo, as a place, has been reconfigured over time: before April 25, 1974, it was an area where inequalities were glaringly evident; it was not a priority area during the Portuguese revolution; and it became a place of refuge once the revolution had ended. In his view, what most urgently required combatting was the Alentejo of the 1960s, whose agricultural and social system was based on the farming of large estates, the symbol of injustice, for which an alternative structure was required-one that the Portuguese Agrarian Reform sought to provide. The fraternity that Giacometti found in the Alentejo cante, from before April 25 and through to his dying days, brought him even closer to the region. This probably explains why he wanted to be buried there, amongst those he had chosen as his own, his coffin draped in the PCP flag.18

A comparison of Michel Giacometti with other authors studied by João Leal reveals that, like Jorge Dias, the Corsican ethnographer discovered Trás-os-Montes and, like Orlando Ribeiro or José Cutileiro, he focused on the south, producing a body of work that was notable for the presence of the working classes and the denouncement of their living conditions prior to April 25, 1974.

Giacometti expressed himself in what may be termed counter-pastoral discourse, just as José Cutileiro did.19 There are, however, differences. For Cutileiro, the social inequalities between rich and poor and the connivance of the rich with the political power in the Estado Novo made life extremely harsh in the Alentejo and transformed it into a repulsive area. For Giacometti, who shared this opprobrium, the landowners’ domination of the workers was condemned by the combativeness and the solidarity of the latter, which he had observed, and the Corsican ethnographer firmly situated himself on one of the opposing sides. Social and political tensions, however, did not dictate his view of this geographical space, and Giacometti felt the same affinity for the southern landscape as Orlando Ribeiro. Michel Giacometti’s discourse was always empathetic towards the Alentejo, seen as the land of the workers whose cultural practices he described and valued during all the phases of his life, but it also had a touch of nostalgia, as if the dream, made possible by solidarity, was still continuing.

Thus, practices and representations came together in Michel Giacometti in a general dedication to “our people” that focused largely on Trás-os-Montes, Beira Baixa and the Alentejo. It was mainly the Alentejo before April 25, or at least one part of it, that, in his eyes, challenged him and led him to act.

Works by Michel Giacometti Alone or in Collaboration

Records

Giacometti, [Michel] (1959). Chants et Danses du Portugal, 2. Traz-os-Montes. Paris: Le Chant du Monde.

Giacometti, [Michel] (1960). Fados. Paris: Le Chant du Monde.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1960). Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. Trás-os-Montes. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1961). Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. Algarve. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1961). Oito Cantos Transmontanos. Francisco Domingues. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Graça, Fernando Lopes; João Gaspar Simões; Michel Giacometti; Sebastião Rodrigues, and Francisco Domingues (1961). Vozes e Imagens de Trás-os-Montes. Book-record. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Graça, Fernando Lopes; Virgílio Pereira; Bernardo Terreiro; António Reis, and Michel Giacometti (1961). Lieder Aus Portugal. Book-record. Hamburg: Christian Wegner Verlag.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1962). Anthology of Portuguese Music, Volume 1. Trás-os-Montes. New York: Folkways Records.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1962). Anthology of Portuguese Music, Volume 2. Algarve. New York: Folkways Records.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1963). Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. Minho. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Estabelecimentos Valentim de Carvalho.

Giacometti, Michel (1964). Visages du Portugal. Paris: Le Chant du Monde.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1965). Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. Alentejo. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Estabelecimentos Valentim de Carvalho.

Graça, Fernando Lopes, and Michel Giacometti (1965). Cantos Tradicionais do Distrito de Évora. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Junta Distrital de Évora.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1968). Bailes Populares Alentejanos. Guitarra: Manuel Jaleca. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Valentim de Carvalho.

Giacometti, Michel (1968). Bonecos de Santo Aleixo. Auto da Criação do Mundo. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Graça, Fernando Lopes and Michel Giacometti (1970). Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. Beira Alta, Beira Baixa, Beira Litoral. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Valentim de Carvalho.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1971). Cantos Religiosos Tradicionais Portugueses. Lisbon: Philips/Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1971). Pequena Antologia da Música Regional Portuguesa. 6 Records. Lisbon: Philips.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1974). Alentejo. Música Vocal e Instrumental. Lisbon: Torralta.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1979). Portugal. Lisbon: Rapsódia/O Canto do Mundo

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1981). Bonecos de Santo Aleixo. 2 Records. Lisbon: Arquivos Sonoros Portugueses/Sassetti/Diapasão/Secretaria de Estado da Cultura.

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (1981). Cantos e Danças de Portugal. Lisbon: Sassetti/Diapasão/Secretaria de Estado da Cultura.

Giacometti, Michel; Fernando Lopes Graça, and Rosário Borges Pereira (1982). Modas Populares do Concelho de Serpa. Audio cassette. Serpa: Câmara Municipal e Comissão Municipal de Turismo.

Giacometti, Michel (1983). Cantos e Ritmos de Trabalho do Povo Português. Homenagem a Fernando Lopes Graça. Audio cassette. No place: Festa do Avante!

Films

Giacometti, Michel (1970-1974). Povo que Canta. Vozes e Imagens para uma Antologia da Música Popular Portuguesa. Directed by Alfredo Tropa. 37 programs. Lisbon: RTP.

Giacometti, Michel (2010/11). Michel Giacometti. Filmografia Completa. Coordinated by Paulo Lima. 12 volumes (no place): Tradisom, Produções Culturais Lda. Edited by Público newspaper. From 22/11/2010 to 7/2/2011.

Published Texts Authored or Edited/Co-edited by Michel Giacometti

Giacometti, Michel, and Fernando Lopes Graça (collab.) (1981). Cancioneiro Popular Português. Lisbon: Círculo de Leitores. With audio cassette.

Giacometti, Michel (1983). Cultura popular portuguesa: as tradições artesanais in Cultura Popular. As Tradições Artesanais. Lisbon: Festa do Avante! edition, 3-8.

Giacometti, Michel (1983-a). Cultura popular portuguesa: as tradições artesanais in Movimento Cultural, 1. Setúbal: Associação dos Municípios, 39-41.

Giacometti, Michel (1987). A agricultura (breves apontamentos) in Museu 1987, 8.

Giacometti, Michel (1987-a). Para a história da colecção in Museu 1987, 4.

Giacometti, Michel (Junho/1988). Alvito, em 26 de Maio, Diário do Alentejo, No. 322.

Works Containing Michel Giacometti’s Collections

Almeida, Ana Gomes; Ana Paula Guimarães, and Miguel Magalhães (coords.) (2009). Artes de Cura e Espanta-Males. Espólio de Medicina Popular Recolhido por Michel Giacometti. Lisbon: Gradiva.

Galhoz, Maria Aliete Dores (1987). Romanceiro Popular Português. I. Romances Tradicionais. (organization, introduction and notes). Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos/Instituto Nacional de Investigação Cientifica.

Galhoz, Maria Aliete Dores (1988). Romanceiro Popular Português II. Romances Religiosos e Orações Narrativas. (organization, introduction, notes, and bibliography). Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos/Instituto Nacional de Investigação Cientifica.

Guerreiro, António Machado (1989). Anedotas. Contribuição para um Estudo, Cerca de 2000 Espécimes. 5th edition. Lisbon: Editorial Império.

Ramalhete, Ana Maria, and Nuno Júdice (coords.) (2009). Romanceiro da Tradição Oral. Recolhido no Âmbito do Plano Trabalho e Cultura dirigido por Michel Giacometti, 2 Volumes. Lisbon: Edições Colibri. Transcription and editing of texts by Miguel Magalhães and Ricardo Marques.

Soromenho, Alda da Silva, and Paulo Caratão Soromenho (1984). Contos Populares Portugueses. Inéditos. Study, coordination and classification. Vol. I. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos/Instituto Nacional de Investigação Cientifica.

Soromenho, Alda da Silva, and Paulo Caratão Soromenho (1986). Contos Populares Portugueses. Inéditos. Study, coordination and classification. Vol. II. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos/Instituto Nacional de Investigação Cientifica.