Among the processions of the monarchical bishopric’s calendar, Corpus Christi was one of the most important in Portugal and its overseas conquests. It was one of the Eucharist’s most solemn manifestations.1 This paper analyses the role of Corpus Christi in producing public and sacred spaces, a kind of holiness in movement and in space made by a collective of believers in the Catholic world.2

For many years I have been consulting works by authors in the field of the anthropological theory of rituals in my research on the Corpus Christi feast and procession (Durkheim 1996: 3-60; Mauss 2003: 181-312; Turner 2008, 1974; Douglas 1984: 63). Corpus Christi is a religious and political ritual that celebrates the redemption of humankind through Christ’s sacrifice.3 It is considered one of the most solemn manifestations of the Eucharist for Catholic devotees in early modern history. As a ritual, it was a complex system of negotiation between groups of different societal ranks (Schmitt 2002: 415-430).

Literature on the procession, including historiography and other fields, such as folklore and ethnography, demonstrate changes in the multi-secular Corpus Christi ritual, particularly in the eighteenth century. Some of these publications present rich sources that have not yet been examined thoroughly (Oliveira 1901: vols. 11-12). Others offer valuable insights as to how different groups contributed to the ephemeral architecture, and how the powerful used urban space to exclude popular and profane aspects of the procession (Janeiro 1988; Tedim 2001; Raggi 2014). However, there are no works that systematically and comparatively examine the transformation of what was to become the most solemn ritual in the cities of the Portuguese empire during the reigns of John V (r. 1706-1750) and Joseph I (r. 1750-1777). This article on Porto’s procession contributes towards this field of research. Through an analysis of historical records from the Porto city council, I will discuss how the Eucharist, a gift given to mankind, came to be expressed in the use of space, particularly concerning material elements (Mauss 2003; Meyer & Houtman 2019: 81-113). These are indicative of changes in the procession in the eighteenth century, which had been a mandatory ritual in Porto since the seventeenth century. Although I will focus on spaces, especially how some of them became sacred, I will also pay attention to the dimension of time and agency, which, combined with space, give a panorama of the socio-religious context.

Officially, the Corpus Christi feast was established in 1264 by Pope Urban IV’s Bull Transiturus de Hoc Mundo, which made the celebration mandatory throughout the Christian world (Rubin 1994). The procession had become part of the liturgy a century later. In the early modern period, there was a strong tendency for the feast to become joined with lay and local powers, which created tensions between religious and secular authorities.

There is documented information about the feast during the reign of Afonso III of Portugal (r. 1248-1279), but it only became one of the festas reais (royal feasts) during the reign of Manuel I (r. 1495-1521), along with two other mandatory celebrations for all inhabitants within a league’s distance from a city centre.4

The Corpus Christi feast and procession were coordinated by different authorities: the bishopric, the monarchy, the city councils, and the confraternities. The first one made up a three-tiered order around the eleventh century; the priests, the warriors, and the laborers, as we see in the work by Duby (Duby, 1982).5 In the early modern history of Portugal, the city council was one of the main authorities coordinating the procession, deciding over all its spatial and temporal aspects. These aspects included the streets the procession passed through, its ornamentation, and the schedule. Furthermore, the city councils decided over its composition, who would participate, and who would carry the poles of the canopy (Oliveira 1885: vol. 1; Gonçalves 1985; Santos 2005; Douglas 1984: 63).

Iria Gonçalves gives a precise analysis of the role of the Porto city council in its Corpus Christi feast, although she studies the second half of the fifteenth century. She points out that the feast was organised by the local church, the city councils, and the artisans’ associations. Although the Catholic Church gave directions concerning doctrine and aesthetics, the city councils provided the materials, which Gonçalves analysed by studying the preserved revenue and expenditure books from 1450 to 1494 (Gonçalves 1985: 6-7). Many of the feast’s components stayed the same, such as the city council deciding on the procession or providing the materials (e.g., sermon, music, and candle wax). However, since my analysis looks at the procession during the eighteenth century, I must pay attention to important changes in early modern history, such as the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the Catholic Enlightenment.

There is documented information from the sixteenth century about the involvement of labourers, which differed in rank, in the procession (Santos 2015: 241-263). The procession was socially stratified: it began with the labour confraternities, then the communities, and finally the lay and religious authorities, who carried the Holy Sacrament. This order was a fantasy because social stratification had become increasingly complex since the beginning of the modern period, and subsequently the ritual was marked by continuous disputes over precedence.

Using the preserved minutes of the Porto city council meetings, I will discuss the alterations made to the Corpus Christi procession during the eighteenth century and focus on how urban space turned into sacred space. These alterations can be summarised as the following: substituting dances, inventions, and other antiquities with awnings and arches.6 Similar alterations occurred in other cities of the Portuguese monarchy: Lisbon, where the court and the patriarchal chapel were located, Rio de Janeiro, and Salvador.7 They are Ars modifications, that is, involving the artisans, who were traditionally given financial support, work and the garments of the cortege.8 As such, the changes made to the procession cannot be considered merely aesthetic. Instead, I argue that they must be understood from a political and religious perspective. The debate on the procession is recorded in the minutes of the council meetings in a specific manner. Since only citizens could attend, the artisan’s participation was restricted in the city council, even though they were at the centre of debate. The city of Porto biased sources from the eighteenth century, “the second of the Reign [after Lisbon] and the first to imitate as closely [as possible] what is done at the Court’.9 However, far from the direct control of the Portuguese Crown, decisions concerning the procession and many of the city’s other affairs were in the hands of the councillors.

According to Francisco Ribeiro da Silva, Porto’s society knew three main groups: the clerics, the nobles, and the third state. Ribeiro da Silva examines how differentiation grew within the three-tiered model during Modern Times (Silva 1985: 2 vols.).10 This paper focuses on the third state, because this group produced useful and ornate objects for the city’s inhabitants (Chastel 1991: 9-36). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, this group provided the procession with financial support, the work and garments.

The top layer of the city council’s administration was occupied by the nobreza da toga, or nobility of the toga. They were citizens, noblemen who had been knighted by the king. During Portugal’s old regime citizens had their privileges given or affirmed by the king, and one of these privileges was political rights. In the city of Porto, citizens happened to be fidalgos (gentry), and they expressed their wealth and power by intervening in the city’s governance.

In 1611, the House of Aziz granted the citizens of Porto privileges such as tax exemptions and permission to carry weapons. These privileges were publicly recognised through the citizens’ place in the Corpus Christi procession, next to the canopy or by carrying poles. The third state was the largest and most heterogeneous group in Porto society: it ranged from the artisans to the merchants. Their status depended on society’s regard for the profession, economic strength, and the honour carried in extra duties they were called upon to do and their proximity to the rulers (Silva 1994: 329). Some of the labourers had more prestigious activities, such as the goldsmiths, chemists, viol makers, oil painters, booksellers, joiners, ship-owners, pilots, and mariners (Barros 1993: 124-136). Because of their good reputation, sometimes goldsmiths and oil painters were made citizens.

Carrying out certain functions was another way to gain prestige. This was the case for those who were involved in the Casa dos Vinte e Quatro, a working-class institution, which was established in cities across the Portuguese Empire, such as Lisbon, Coimbra, and Salvador. In Porto, the institution was active from 1518 to 1834, except for the period 1757-1795, but overall little is known about it. Originally, as the name indicates, the leading traders and craftsmen elected 24 (vinte e quatro) representatives. They could only participate in the economic affairs of the city: first, at mass, the presence of all 24 or 48 representatives made a strong impression during council meetings. Second, two of their representatives called procuradores dos mesteres would sit in on all the meetings but only voted on economic matters. The procuradores dos mesteres and juiz do povo enjoyed a higher standing than their peers. In Porto, the most common representatives were shoemakers, coopers, and barbers, who constituted the largest contingent of the city’s labourers.11

According to a ruling of 1621, the leading trades and handcrafts were responsible for the dances, the andores (parade floats bearing sculptures of saints), and several kinds of decorations.12 The richness and variety of these elements are hard to describe. For example, the female bakers contributed to the procession with the péla, a type of dance that involved twelve women with tambourines and small hand-held drums. The regateiras, the city’s small vendors, also put on a péla. Alternatively, they carried little girls on their shoulders and rolled their hips.13 The shoemakers prepared figures of the king and Saint John the Baptist, a banner, as well as a dance with satyrs and nymphs. The gold- and silversmiths were obligated to provide twelve torches. Bakers, regateiras (marketmen, referred to as hagglers), and smiths were respectively positioned ninth, eighteenth and twenty-first in the procession, ordered according to increasing social importance.

Meeting minutes from the first half of eighteenth century describe artisans’ petitions to the city council to negotiate their contribution to the procession. Thereza Pereira, inhabitant of Vila Nova, a parish of Porto, requested the city council to select another female resident to give the péla the following year. It is important to remember here that participation was mandatory for inhabitants within a league’s distance from the city centre, which included the city proper and often the surrounding countryside.14 This source shows that Pereira was responsible for the péla (either financially or by coordinating the dancers), a significant contribution and a sacred job, which was publicly announced in the cathedral.15 Pereira had verbally abused the female assistants, who had not proposed a candidate to take her place, or her “ministry”. Thereza also requested the councillors to arrest the regateiras so they could carry out their obligation in prison. We can see from this source that she was responsible for giving the péla (either financially or by organizing her coworkers), a significant contribution and a sacred function, publicly stated at the cathedral. The regateiras belonged to one of the city’s lowest orders of labourers, because they generated their income from interacting with the common folk.

In 1729, the female bakers of Porto successfully lobbied the council for a royal edict changing their contribution to the procession from a péla to andores, which had also happened in Lisbon four years earlier (Albuquerque 2001: 47-55).16 Such demands appear to have occurred frequently and were caused by different circumstances, such as economic burden, disease, the disappearance of some crafts, and informed by notions of nobleness, “seriousness”, and “solemnity”. The first documented change to the Corpus Christi procession is from 1734.17 The minutes record a proposal presided over by the juiz de fora, the councillors, and the procurador da cidade,18 which stated that artisans were henceforth obliged to pay for the awnings along the route of the cortege instead of the dances. The awnings were a kind of ephemeral architecture used to decorate the procession’s route. The idea was to share the cost among the artisans and traders - one or two people representing the seven parishes of the city proper and its countryside19 - such as the merchants and cloth merchants with draper’s shops. They were tasked with donating the awnings for the “Street of Flowers” instead of the “Little Shepherd’s dance”. This was achieved through the four or five percent tax paid by artisans and traders who represented a parish for a stretch of the route. Each elected person was nominated, sometimes including their declared profession and address. It can be surmised that the majority was substituted in the minute to avoid being a tax collector and responsible for the new direction of the municipal council. The proposal was nonetheless implemented that very same year and the year after the change to the procession was approved by the council.20

From 1734 the procession was increasingly up for discussion. One man appealed to the council for more time to talk with the other merchants, but a justification for said change is missing.21 In 1735 the notion of an “order” in the procession appeared. Porto thereby imitated the churches of the Lisbon patriarchy and West Lisbon, where this subject had already come to pass (Albuquerque 2001).22 The minutes of this meeting specify that the procession should be ‘[w]ithout andores, dances, or [inventions], [and] only [consist of the attendance of the] Brotherhoods and communities, clergy, and Chapter, […] ornamented windows, and [for] all the streets [to be filled with] the inhabitants and […] the craftsmen […]’.23 The document thus excludes the procession’s traditional, popular elements and through sobriety seeks to underline the “Solemnity” of the day. This included punishment (both fines and imprisonment) for non-compliance, as well as dictating where each artisan from each district should be for the whole route.24 The first part of the procession’s route was paid for by the city council, which contributed towards the awnings and arches from the “See door” to the “Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Vandoma”. The minutes of this 1735 council meeting were repeated almost entirely in 1773, indicating that this new direction for the procession was relatively successful.25 To better contextualise this new direction, which I argue transformed the city into a sacred space, I will discuss some of the disputes that took place in the 1750s.

In February 1752, Luiz de Amorim, the procurador da cidade, tabled the motion to return the procession to its old format according to regulation of 1621. De Amorim’s motion was approved, overturning the changes made to the procession in 1735. The minutes show that the changes made to the procession had not been approved by the monarchy, and that the awnings were more expensive than the dances and traditional customs performed by the artisans. The councillors describe how the craftsmen decided to reinstate the various dances, andores, inventions, and instruments. The latter were played on the eve of Corpus Christi and on the day of the feast. The artisans’ butlers would have with them a list of all artisans, who had in all likelihood signed the petition to overturn the changes.26 In May, Jopseh I of Portugal published an edict which forbade all dances and masks during the feast of Corpus Christ. This counteracted a prior petition in which the noblemen and inhabitants requested the monarchy to reinstate the old format and the current format of the feast of the Holy Cross in Vila Nova de Gaia.27 These documents suggest that the discussion about the procession had turned into a conflict. The rise and fall of old and new customs was thus not limited to Porto, but also played out in other cities of the Portuguese Empire, such as Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, and Salvador (Oliveira 1889: vol. 1, 1; Santos 2005; Flexor 1974: 24).

In 1773, the new pattern was again approved. The minutes of the council meeting of 2 July included an introduction, a kind of map of the procession, and recorded the values that the advocates of this change wished to uphold for future reference. The introduction is a proposal of sorts which aims to justify the changes made.28 The councillors used the concepts of “solemnity”, “decency”, and “piety” to justify abolishing the dances, the characters, the inventions, and the andores in favour of awnings, decorative fabrics, and the exclusive veneration of the Holy Sacrament. The concept of “decency” is repeated in the same document, as was common in the early modern period. According to Rodrigo Almeida Bastos this concept was associated with the “doctrine of decorum”, with which it shares an etymon, decens, meaning “that which is appropriate”. In historiography, this concept has been interpreted through a moral lens, focussing on the development whereby profane and impure elements were banned from religious art, at the time when appropriateness and decorum in religious affairs held broader meanings. This historiography has established that the “decorum” was adopted from classical texts and developed by several Catholic authors to legitimise public worship. One of the movement’s main figures was Carlos Borromeu, whose work adapted the precepts established by the Council of Trent (1545-1563) into a religious architecture. His work is mostly concerned with the concepts of “decorum” and “piety” (Bastos 2009: 34-101, esp. 39-40).

The Enlightenment influenced Catholicism in Portugal since the reign of John V (r. 1706-1750). During the reign of his successor, Joseph I (r. 1750-1777), these ideas not only produced more public debate, but also found followers amongst the clerics and lay people, and subsequently spread throughout society. Especially after the 1760s the Portuguese monarchy supported reforms in the cultural fields (education, pastoral ministry, etc). While research concerning Portugal’s Catholic Enlightenment is still ongoing, it is becoming increasingly clear that Catholic thinkers like Luiz António Verney (1713-1792), Friar Manuel do Cenáculo de Vilas Boas (1724-1814), and the group of Jabobeu bishops led the Catholic reforms in Portugal during this period.29 They were in favour of forging a more educated clergy, with proper theologians with a rounded training in biblical exegesis and in ecclesiastic history. They also desired a disciplined congregation, reducing the number of saints, pilgrimages, and other practices they considered superstitious. In short, these thinkers pursued a “regulated devotion”, to borrow an expression from Ludovico Antonio Muratori (1672-1750), one of the most influential thinkers among the Catholic reformers, whose work influenced others like António Pereira de Figueiredo (Muratori 1747: 378; Lehner & Printy 2010: 1-62; Souza 2010: 359-402).

Despite the changes proposed for the Corpus Christi procession in 1773, some of the inhabitants and artisans were still expected to maintain certain traditions, such as cleaning the streets and the facades of buildings, as well as and decorating the parade’s route.30

The changes to the procession proposed in 1773 originated from Lisbon, the seat of the monarchy and the patriarchy, which, according to the city council minutes, served as a model for the city of Porto. It seems likely that not everybody accepted the changes made by the proposal, because the city council repeated the proposal twice, in 1774 and 1779. In 1780, Queen Maria I (r. 1777-1816) declared that the proposal of 1773 would become a royal custom.31 Contemporaries felt that the changes made to the procession were appropriate in light of the Enlightenment and wished to do away with the old customs and practices. However, the religious significance of these alterations followed the principles of the Catholic Reformation of the sixteenth century, which were applied from this period onward through the bishoprics.32 For the Catholic Church, the changes made to the procession indicated growing control over the faithful and the public expressions of their faith.33

In the case of Porto, I have identified several of the reform’s supporters: Miguel Menguelo, procurador da cidade, who tabled a proposal in 1773 and was supported by the present councillors and perhaps several craftsmen and traders as well. The changes were modelled on the altered procession of Lisbon, which in turn followed the example of Rome’s procession. The changes were demanded by Don Frei João Rafael de Mendonça, the Bishop of Porto from 1771 to 1793 (Basto 1947; Bernardi 2000: 228-242).34 He was born into the aristocracy and favoured the Marquis of Pombal, who ruled the Portuguese Empire from 1750 to 1777 as chief minister of Joseph I (Brásio 1958: 165-233).35 The bishop made his entry to the city in 1772, a year before the proposed changes to the procession. Perhaps he sought to reinforce the universal cult of the Eucharist by updating the procession.

Awnings were a strong sacred symbol during the Corpus Christi processions in the Portuguese Empire during the eighteenth century. The term toldo possibly derives from Latin tholos, which means dome-shaped or a pinnacle, the highest part of the temple where the ancient Romans hung vows to their “false divinities” or could also refer to the roof of a round chapel. The Portuguese word kept a similar meaning.36 The awnings were a roman curial fashion already in use, but that were introduced systematically by order of king D. John V at the Lisbon procession from 1717 and onward, although there were other material and/or symbolic elements which were brought together. These elements could be connected with the establishment of Lisbon’s patriarchy, which combined with the notion of “order” underlined the ban on old procession customs. Such as the reinforced exclusion of several figures, the floats, the dances, and the muslins which used to bear the figure of Saint George. Conversely, the dated canopy was replaced by a more lavish canopy, and chains were used to block streets that crossed the route of the procession. Order also meant that artisans had their addresses and confraternities registered, which in turn dictated whether one would join the West or East Lisbon procession.37

Why do I argue the awnings were a strong symbol? Selecting the sources about Lisbon’s procession from 1717 to 1723 as a sample there were around thirty-three documents recording this celebration and nineteen of them concern the awnings.38 In 1717, John V tried to pass the expenditure of the awnings on to Lisbon’s inhabitants. Some councilmen resisted and argued that it would be difficult for the city’s artisans to afford the expensive awnings. Instead, they proposed transferring some of the council’s resources that were intended for public utilities, as well as putting new taxes on wine, salt, or meat. The councilmen also considered the idea of commonwealth, means such as an auction to pay for the awnings. Additionally, the minutes illustrate that the councilmen recognised the importance of the Blessed Sacrament because they discussed the proper height, colour, and fabric of the awnings.39 John V nevertheless upheld the decision: ultimately, the city council would have to pay for the awnings and the columns, proposing that a private person would have to finance them in advance.

The King had also made João Frederico Ludovice (1673-1752), a German born architect and goldsmith, responsible for overseeing the placement of the procession’s awnings in West and East Lisbon in 1719.40

After this particularly ornate procession, a debt had been worked up and the workers were left unpaid. The discussion about the awnings occupied many council meetings and the city remained in debt for years to come.41 Looking at the budget for (both parts of) Lisbon, the city councils spent 5:600$000 to put up the awnings, the columns, and to decorate the buildings and streets on the procession’s route. According to the same budget, the councils annually spent 6:750$000 on the repair and construction of pavements, repairs to fountains, and other maintenance (Oliveira, 1903: vol. 12, 96-99).42 Comparing these numbers, it is fair to conclude that the awnings for the procession were an important issue, one of great expense, and that the cost of these decorations was both a financial and a political burden.

In Porto, the city council sought to share the costs of the procession with the traders and artisans. A great deal of discussion concerning the procession’s budget is documented in the minutes of the council meetings. Between 1785 and 1796, the council organised auctions to pay for the awnings in advance - with the exception of 1789.43 This money was spent on the part of the route the city council was responsible for. For the procession of 1796, four men were elected by the council: Antonio Jozé da Cunha, Jozé António Guimarães, Manoel Jozé Duarte, and Francisco Jozé Gomes Monteiro, two with identified professions: the third was a shop assistant and the last one, a merchant. Manoel Jozé Duarte belonged to the house of Antonio Ribeiro de Faria, who probably owned the house and shop, but another man was named as his guarantor. The sum raised for financing the awnings, columns and decorations from the Cathedral door to Vandoma Arch in 1795 and from the Episcopal Palace to Vandoma Arch after 1796 averaged from 12$000 to 33$600.

The earthquake of 1755 brought about great changes to Lisbon, as well as its procession. Yet the notions of “solemnity” and “piety”, as well as the memories of the 1719 Feast of Corpus Christi, were kept alive. In 1719, the papal legate stated that ‘the city centre [of Lisbon had] looked like a formal church, ornate and covered on all sides, so that hardly any air could get in’ because of the many awnings and columns along the streets of the procession.44 Ignácio Barbosa-Machado’s eulogy praised John V, because, like God, the King had created for “only a minute, the whole machine of the sky, and the earth” by giving the streets the appearance of a temple (Barbosa Machado 1759). By quoting Saint Augustine, this eulogy demonstrates how power and the idea of the Corpus Christi procession were perceived at the time, as though the earthly city of Lisbon had become God’s city for one day. Even though the awnings had been in use since the sixteenth century, the ephemeral temporary architecture decorations of 1719 were part of a project to emulate Rome, the capital of the Catholic Church and birthplace of the Roman Empire (Raggi 2015: 463-493).

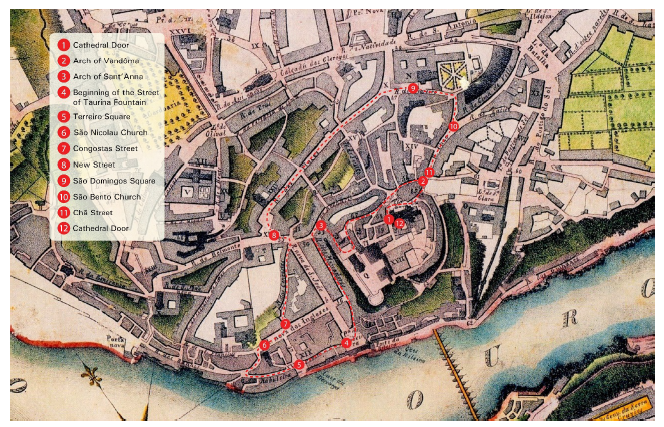

Returning to 1773, the council meeting minutes also explain which parts of the route were assigned to each craftsman. The list contains the names of approximately fifty artisans and traders, who were instructed to take specific positions. The representatives to the city council were exempted because they were instead responsible for putting up the awnings at the start of the procession.45 Using these minutes, it is possible to reconstruct the route, which is a circuit from the cathedral and back.46 The cyclical character of this feast, the procession, also affirmed the sacredness of certain spaces and rendered other sacred. The procession, through its movement and decorations, established a narrative manifested into urban space. In this sense, as with the pilgrimages analysed by Victor Turner, Porto’s Corpus Christi Procession were a topographic ritual, a distribution of permanent sacred places, which coexisted and contended with the city’s political topography (Turner 2008: 172). The procession route from the seventeenth century is shown on the map from 1813 below.47

It is important to highlight the urban spaces that the eighteenth-century processions passed through, where the processions took breaks, and fountains artisans and traders were tasked with decorating. At first glance, it seems that the Corpus Christi procession connected the upper city, which had been built around the city’s episcopal see, with the lower city on the shores of the Douro, which had developed to serve maritime trade (Janeiro 1988: 729).

The episcopal see was the starting point of the procession. Its public ornamentation was the responsibility of the city council and was financed with auctions relying on private financial support. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the council’s decorating duties shifted from the cathedral to the Episcopal Palace, both buildings radiating episcopal power.48 The minutes also cite two doors in Porto’s medieval city wall, which besides allowing for the procession to pass through, were also city monuments to be visited by the cortège.49

Figure 1: Map, Planta Redonda de George Balck (1813). Source: Câmara Municipal do Porto/Arquivo Histórico Municipal do Porto: AHMP, F-NP/CMP/7/3097.

The churches mentioned in the minutes of 1773 belonged to important civic institutions. First, the Igreja Paroquial de São Nicolau, or the Church of St Nicholas, a parochial temple still in use today, where the brotherhood of goldsmith was installed. This was an association of artisans that enjoyed great prestige during the eighteenth century. Second, the Churches of São Domingos and São Bento, which were associated with the regular orders. Although these churches no longer exist, they were the focal point of the city squares and consequently for the route of the procession at the time. The streets the procession passed through typically had some social importance. For example, Chã Street lay on the route, which is where much of Porto’s nobility resided (Silva 1994: 318).

The fontes or chafarizes were located in public places and also recognized as an architectural element of the city.50 All the fountains mentioned in the minutes of 1773 were within the city walls, although sometimes the requested decorations referred to fountains from beyond the walls. The Fonte Taurina was probably the oldest fountain of the city, and its first name was associated with the presence of gold, since the square it was on was used as a marketplace. The Fonte de São Domingos, situated on above mentioned square with the same name, was the meeting point for councillors between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries. Nevertheless, the water chargers were mainly at the Quingostas Fountain, in the east side of it. The Fonte de São Sebastião was located near the first city council’s main buildings, their seat of power, and the Casa dos Vinte e Quatro (Silva 2000: 32, 202-203, 250, 24-285).

The route was taken by these groups of whose various roles in the procession have been the subject of this paper: the bishop, the councillors, and the artisans. Their shared and individual narratives transformed an earthly assembly into the sacred even though their roles and power were deeply asymmetrical.51 I have argued that by the end of the eighteenth century, the procession had a more permanent route, it had become more solemn, and the popular and traditional elements had partially disappeared. Moreover, the elite expected a more disciplined congregation of the faithful, in accordance with the growing demand for “solemnity”.

I have considered the Corpus Christi procession in Portugal through the notion of “sacred space” and by consulting the records for the historical use of “urban space” since the beginning of the Corpus Christi procession in Portugal. During the eighteenth century, as shown by my analysis of Porto’s procession, space became increasingly sacred because of the gained popularity of notions such as “solemnity”. In other words, the dances, characters, inventions, and other traditions were replaced by awnings and arches. Transforming the streets with the ephemeral architecture was one of the ways the Catholic Portuguese manifested their public devotion of the Blessed Sacrament. It was, in a sense, an eighteenth-century update.

Although this focus on the route, sacred space, and material objects are important components of understanding the Corpus Christi procession, these aspects are not sufficient. As seen in the ecclesiastical notions of procession and particularly in the Corpus Christi procession of Porto, the ritual consisted of a variety of elements. Some were more concrete, such as the awnings, the canopy, the leaves, while others were not so tangible such as music and prayers. To better understand the role of religion in the early modern period, attention must be paid to a combination of elements: the construction of power, practices and rituals, as well as material objects.52

The changes that took place in the Corpus Christi procession of Porto happened in several cities of the Portuguese monarchy I argue that these changes must be placed in a broader context of the Catholic Enlightenment. This paper has focussed on the procession’s material elements, which I believe are exemplary for broader developments taking place in Europe at the time. These changes reinforced concepts rooted in the Catholic Reformation, such as the centrality of the Blessed Sacrament and its importance in religious events, the role of the bishops as pastors, and the Catholic Church’s efforts to eradicate churchgoers’ superstitions and profanities. However, it was only during the last decades of the eighteenth century that Porto’s Corpus Christi procession was made into a ceremony, for which the public/faithful were informed how to participate in this ritual which celebrated the gift of redemption with due solemnity, simplified devotion and which required the discipline of the congregation and social order. This transformation happened, as demonstrated by the case of Porto, through a process of conflict and consensus between the clerics and the laity. Both parties would increasingly receive directions from the enlightened authorities at the head of the monarchy.53

I know that there is a connection between the Corpus Christi procession, which acted as a standard for other festivities and vice-versa, that requires further research. Furthermore, this paper touches on how Portuguese processions imported elements fashionable in Rome, a nexus that deserves more attention. Interestingly, the traditional dances that were abolished from the Corpus Christi procession were preserved in other royal feasts, such as royal births, anniversaries, and weddings celebrated in Lisbon, Porto, and Rio de Janeiro between the eighteenth and nineteenth. Why was this the case? More research can hopefully shed light on the heterogeneity of collective life, and the ebbs and flows of change and restoration.

References

Printed sources

Almeida, Candido Mendes de (ed.) [1870]. Codigo Philippino, ou, Ordenações e Leis do Reino de Portugal : recopiladas por mandado d’El Rey D. Philippe I. Liv. I, tit. 66. Rio de Janeiro : Typ. do Instituto Philomathico.

Bluteau, Rafael, Vocabulario Portuguez e Latino. 1712-1728. Coimbra: Collegio das Artes da Companhia de Jesu

Constituições primeiras do Arcebispado da Bahia [1853] S Paulo: Na Typ. 2 de Dezembro de Antonio Louzada Antunes.

Constituições Synodaes do Arcebispado de Lisboa [1656]. Lisbon: Off. Paulo Craeesbeek.

Constituições Synodaes do Bispado do Porto [1690]. Coimbra: Joseph Ferreyra.

Costa, Pe. Agostinho Rebelo da (1789). Descripção topografica, e historica da Cidade do Porto: Que contém a sua origem, situação, e antiguidades: a magnificencia dos seus templos, mosteiros, hospitaes, ruas, praças, edificios, e fontes... Porto: Officina de Antonio Alvarez Ribeiro.

Machado, Inácio Barbosa (1759). Historia Critico-Chronologica da Instituiçam da Festa, Procissam, e Officio do Corpo Santissimo de Christo no Veneraval Sacramento da Eucharistia. Lisbon: Off. Patriarcal de Francisco Luiz Ameno.

Muratori, Ludovico Antonio [1747]. Della regolata divozion de' cristiani. Venezia: stamperia di Giambatista Albrizzi q. Gir.

Ordenaçoens do Senhor Rey D. Manuel. [1797] Liv. I. Coimbra: Na Real Imprensa da Universidade.

Voelker, Evelyn Carol (1977). Charles Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae Et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae, 1577: A Translation with Commentary and Analysis. 2 Vols. PhD thesis, Syracuse University.