Introduction

“Si ka badu, ka ta biradu.” (If one does not go, one cannot return.) - Eugénio Tavares, Cabo Verdean poet, 1962

A Google Scholar search for academic texts that combine the words “emigration and citizenship” provided the suggestion, “Did you mean immigration and citizenship,” and yielded only 95,400 results, whereas the search for “immigration and citizenship” generated 714,000 results. Considering that, as emphasized already by Sayad (1977), every immigrant is, initially, an emigrant, the fact that emigration states and their relationship with their external citizens has not received much attention in scholarly research is symptomatic of what Sayad (1977) termed an “ethnocentric way” of conceptualizing the impact of migration. In recent decades, however, there has been a renewed interest in the phenomena of transnationalism and external citizenship in the context of emigration states. This has challenged the paradigm of “methodological nationalism” (Wimmer and Glick Schiller 2002) informed by the assumption that nation-states and society are the natural social political forms of the modern world and thus, domestic policies beyond borders are a deviation from the traditional notion of the territorial nation-state.

Going beyond the default assumption that “emigration states are disinterested with respect to their diasporas” (Bauböck 2003), a rich literature emerged focusing on different questions supported by different theoretical frameworks. From research on the practice of sending remittances (Durand, Parrado, and Massey 1996; Åkesson 2010), to political participation (Bauböck and Faist 2010; Batalha and Carling 2008; Schiller and Faist 2010; Vertovec 2009), diaspora engagement (Cohen 1996; Gamlen 2006; Dufoix 2008; Brubaker 2005; Lopes and Lundy 2011), and second-generation engagement in homeland development (Graça 2013; Lima-Neves 2009), there has been widespread recognition that migrants “do not delink themselves from their home country, instead they keep and nourish their linkages to their place of origin” (Itzigsohn 2000: 317).Against this backdrop, this paper examines the ways in which emigration is compelling states to redefine their conceptualization of the notions of “citizenship” and “nation-state” in order to incorporate external citizens as part of the political community. It examines the Cabo Verdean case as an emigration state par excellence, which has, historically, maintained consistently strong ties with its emigrant communities all over the world.

A small, barren and isolated archipelago, Cabo Verde has prospered because of migration opportunities (Carling 2004). In light of the mismanagement of the archipelago by the Portuguese administration during the centuries of colonialism, which led to multiple famines that eradicated more than half of the population by the 1800s1 (Carreira 1977), emigration, characterized by a strong engagement with the home country, became a structural aspect of the Cabo-Verdean society (Grassi 2006; Åkesson and Baaz 2015; Åkesson 2010; 2016), thus contributing to the development of transnational lifestyles within the archipelago predating the founding of the nation-state (Lima-Neves 2009; Lopes and Lundy 2011; Åkesson 2010; Graça 2013; Batalha and Carling 2008).

While Portuguese is the official language, the Cabo Verdean Creole (Kriolu) is emblematic of both the language and identity that unites Cabo Verdeans on the archipelago, but also across the four continents bordering on the Atlantic Ocean where diaspora communities have settled . (Batalha and Carling 2008) The presence of the Creole language in the archipelago dates back from the 1580s, making it one of the oldest and most studied Creole languages in the world (Alexandre and Gonçalves 2018).

Today, despite being considered a top emigration country2 and among the most migration dependent in the world3 (Carling 2004; Ratha, Eigen-Zucchi, and Plaza 2016), the islands have a reputation for “good governance” and respect for democratic principles (Baker 2006; Meyns 2002). Nevertheless, its “practice” and experience of external citizenship (Bauböck 2009) through emigrant external voting has received scanty research attention. Most of research has focused on the importance of remittances (Carling 2004; Åkesson 2010), on knowledge transfers (Åkesson 2016; Åkesson and Baaz 2015), and on the transnational lifestyle demonstrated by the Cabo Verdean diaspora (Batalha and Carling 2008; Andrade-Watkins 1987 & 2015; Åkesson 2010). Recent research has emphasized the links with the second-generation in Europe (Graça 2013) and the United States of America (hereafter USA) (Lopes and Lundy 2011), and also the engagement of the diaspora in homeland development (Lima-Neves 2009; Åkesson and Baaz 2015).

Transnationalism and External Citizenship

Traditionally, research on migration studies has tended to focus on theories of assimilation and acculturation of international migrants in the societies of the country of residence (Vertovec 2009; Gamlen 2008). Consequently, a vast array of research on the integration of immigrants followed. Critics such as Sayad (1977) were already pointing out in the 1970s that there was too much emphasis on the “immigrant phenomena” and that the other side of the coin, i.e., the emigrant status of every immigrant, was being ignored by social science researchers.

Currently, it can be argued that global migration is “disrupting tidy concepts of nation-states as bounded territorial entities with fixed populations of citizens” (Wimmer and Glick Schiller 2002; Barry 2006: 17), and in the past two decades there has been a significant increase in the number of states engaging with their emigrant communities (Bauböck and Faist 2010; Brubaker 2005). This has, in turn, led to transnationalism as a theoretical framework, becoming one of the fundamental lenses through which to view contemporary migrant practices across the full range of social sciences (Vertovec 2009) by addressing social, economic, and political processes that transcend national borders (Villa-Torres et al 2017). This epistemological revolution which started in the 1990s challenged models of “closed societies” and of exclusive loyalties of citizens towards single states developed by traditional political theorists (Riccio 2001).

Consequently, new forms of political action and citizenship that transcend territorial and political state boundaries have emerged. The idea of citizenship, today, is associated with the “membership of a particular political community that entails basic rights, legal obligations and opportunities to participate actively in political decision-making” (Bauböck 2009: 475). As argued by Barry (2006: 16), citizenship necessarily constructs “the polity that defines the nation.” It is therefore not a passive status like that of nationality. Citizenship requires action and practice (Marshall 1992) by means of which states define the people and subsequently the nation. Legal scholars define citizenship as a relation between a state and its members in which persons are assigned a legal status (Bauböck 1994). However, this relationship necessarily changes when citizens leave the territory of their home country (Collyer 2013). Emigration, therefore, requires that both the state and its non-resident citizens actively take steps to redefine their relationship (Bauböck 2009; Collyer and Vathi 2007).

From the perspective of the state, Lafleur (2013) argued that a change in attitude of emigration states occurred at two levels almost simultaneously: on the one hand, at the discursive level, as suggested by Waterbury (2010), states adopted a new rhetoric of “global nation” whereby the idea of nationhood extends beyond the traditional borders of the nation-state to incorporate emigrant communities. This strategic change led countries such as India, Mexico, and Morocco to revise the way in which they presented emigrants to the home society, shifting the discourse from considering them as deserters to presenting them as a valuable resource, sometimes even national heroes (Durand, Parrado, and Massey 1996; Collyer 2013; Khadria 2001).

An example which is often cited in the literature is that of Haiti, which went as far as redefining the national boundaries of the nation-state to become an extraterritorial entity incorporating the multiple spaces where the diaspora-officially named the eleventh department by the then head of state-is located (Collyer 2013; Laguerre 2006; Lafleur 2013; Bauböck 2009). On the other hand, at policy level, home countries adopted policies that incorporated and accommodated the specific needs of the emigrant population (emigrant bank accounts, tax advantages, investment opportunities, provisions for dual citizenship, etc.) (Lafleur 2013; Gamlen 2006; Barry 2006; Waterbury 2010; Østergaard-Nielsen 2003). Some states have also created state institutions, dedicated agencies, administrators, departments, consultative bodies, and sometimes even ministries to administer the relations with emigrants.

It is in this context that the concept of external citizenship emerges. Bauböck (2009: 475) defined it as both a legal status (granted by the state), “of holding the citizenship of a State where one does not live” and a “practice” emerging from emigrant’s practices of maintaining links to the home country polity through voting in home country elections from outside the national territory. Hence, it is through practicing external citizenship that there can be an ongoing relationship between emigration states and their citizens who are absent from the national territory, either temporarily or permanently (Barry 2006). Hartmann (2015: 907) developed a more state-centered approach and defined external citizenship as “provisions and procedures, which enable some or all electors of a country who are temporarily or permanently outside the country to exercise their voting rights from outside the territory of the country.” Lafleur (2013: 3) added that it is “the operation by which qualified non-resident citizens, as defined in the electoral legislation, are added to the electoral roll of citizens residing abroad.”

As the exercise of citizenship is closely associated with active political participation (Marshall 1992), external voting has become the most significant tool through which emigrants practice their external citizenship. It is a mechanism of inclusion in the polity, which has had several names attributed to it over time, such as out-of-country voting, expatriate voting, diaspora voting, absentee voting, absent voting, emigrant voting, extra-territorial voting, transnational voting, distance voting, and remote voting (Lafleur 2013).

As demonstrated by Ellis (2007), the practice is not recent. In the Roman Empire, Emperor Augustus allowed senators in newly founded colonies to send their votes to Rome by mail. The practice became more generalized in the 1900s, when states such as Canada (1915), the USA (1942), the UK (1945), India (1950), Indonesia (1953), and Colombia (1961) recognized the right of external voting, albeit under very restricted conditions, applying only to citizens on foreign missions to serve the state, such as military and diplomatic personnel. These measures were, therefore, not aimed at emigrants, who were at the time mostly (with a few notable exceptions) seen as poor, uneducated “deserters and undesirables” who broke ties with their countries of origin (Lafleur 2013) and left for good.

The end of World War II saw more countries opting for external voting legislation, and indeed today, as illustrated by the worldwide project International IDEA Handbook on External Voting (Ellis et al 2007), the practice of external voting is widespread with over 100 countries adopting such legislation in one form or another. Coyller and Vathi (2007) found that about 115 countries allowed some form of external voting, while Lafleur (2013) more recently added that the number has increased to a total of 130 countries and territories. Thus, although not much attention has been given to the phenomenon by social scientists, the practice has boomed in recent years (Lafleur 2013; Boccagni, Lafleur, and Levitt 2016).

Lafleur (2011) concluded in his study about external voting in Mexico, Italy, and Belgium that, although it is easy to argue that only poor countries that depend on remittances would pass external voting laws, a closer look at the list of countries that allow such practice contradicts this widespread view. Boccagni (2016) argued in his study on external voting among Ecuadorian immigrants in Italy that no systematic correlation has been found between emigrant enfranchisement and the relative weight of the emigrant population or their remittances. Thus, there has been an overemphasis in the still exiguous literature on the normative aspects of external voting, to the detriment of research on the electoral participation of emigrants (Boccagni 2016).

In addition, despite becoming a widespread practice, the idea of electoral campaigns happening outside the borders of the relevant national territory and homeland-oriented political engagement still triggers “classic Westphalian fears” of dual loyalties and the import ethnonational and religious conflicts (Collyer 2013; Schiller and Faist 2010; Lafleur 2013; Boccagni et al 2016). This became apparent in the recent diplomatic crisis between the Netherlands and Turkey after the government of the former decided to ban some of the Turkish prime-minister’s rallies in its national territory, arguing that they ought to give priority to their own national elections, which were due to start soon (Tharoor 2017). Canada has also explicitly declared its reluctance to being considered a “foreign electoral constituency” or an “extra-territorial constituency” defined as “a voting district or riding determined by a foreign state to include territory in Canada.” It has officially announced that it does not allow for its territory to be included as any of such constituencies (Government of Canada 2011). It does, however, accept the practice of absentee voting within its territory. This has led to much criticism mainly because of the inherently multicultural characteristic of Canadian society.

Despite some authors arguing that globalization and transnationalism undermine the salience of national sovereignty and citizenship through the creation of “deterritorialised” forms of citizenship, it is important to recognize that transnational political spaces cannot emerge independently of state-based systems of citizenship (Bauböck 2003a; Collyer 2013). Moreover, no contrast can be made between transnational and national politics as the former is dependent on the latter (Bauböck 2003a). Thus, one ought to be cautious not to confuse “extra-territoriality” with “deterritorialization," as recognizing the existence of emigrant nations is not about a general undermining of state sovereignty through processes of economic globalization. Emigrant nationhood is a connection between states and extra-territorial populations that tends to expand rather than shrink the powers of States (Collyer 2013).

Locating External Citizens: History and Geography of Cabo Verdean Emigration

A small archipelago of ten islands totaling 4.033 km², located approximately 500 km off the coast of Senegal in West Africa, Cabo Verde was uninhabited when the Portuguese arrived in there in the fifteenth century. Its current population numbers around 500,000 people (World Bank 2019) scattered across nine islands: Santiago (the biggest and most populated), Santo Antão, São Vicente, São Nicolau, Boavista, Sal, Maio, Fogo, and Brava. The tenth island, Santa Luzia, remains uninhabited.

The archipelago is devoid of natural resources and its climate is semi-arid with a very short and irregular rainy season from August to October. Apart from the dearth of precipitation, the archipelago’s soils are mostly bare and organically poor, with only an estimated ten percent of its area suitable for agriculture (AfDB 2012). For that reason, emigration was historically seen as the only solution for many poor Cabo Verdeans, resulting in a sizeable diaspora scattered around the world, believed to be larger than the national population (Carling 2002; Batalha and Carling 2008; Nascimento 2008).

The history of emigration from the archipelago is characterized by multiple waves (Carling 2004; Carreira 1977). At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Cabo Verdean emigrants joined Southern Europeans as seamen of the whalers sailing to the United States (Andrade-Watkins 1987 & 2015; Lima-Neves 2009). Alongside Azoreans, Madeirans, and continental Portuguese, Cabo Verdeans are reported to have been living in New England as early as 1820 (Meintel 2002; Lima-Neves 2009; Andrade-Watkins 2015).

The 1940s were a period of significant migration due to severe famines, which saw about a quarter of the total population die (Batalha and Carling 2008). Cabo Verdeans moved to different parts of Africa, including Senegal, Angola, and South Africa (Graça 2013; Cardoso 2012; Batalha and Carling 2008). Furthermore, there was also a significant number of Cabo Verdeans who were sent to São Tomé and Principe during the colonial period as indentured labor (Seibert 1999; Batalha and Carling 2008). To this date, Cabo Verdeans constitute the majority of the foreign-born population (50.3%) in the archipelago (INE 2012).

From the 1960s onwards, a new migration chain began towards Western Europe, first facilitated by Portuguese construction companies who brought Cabo Verdean workers to Portugal (Batalha and Carling 2008). After 1975, migration to both the U.S. and Europe continued but in much reduced numbers due to the restrictions introduced in host countries (Carling 2004).

Today, the main emigrant communities are in the U.S. (mostly located in New England), Brazil and Argentina in the Americas, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands in Europe, and Senegal, São Tomé and Principe and Angola in Africa. The links between these communities established in more than twenty-five countries around the world (Carling 2002; Avelino Carvalho 2010; Åkesson 2016; Batalha and Carling 2008; Lima-Neves 2009) and their home country go beyond just economics, they are also psychological (Carling 2002). These are expressed through feelings of sodade,4 a sentiment of longing for the homeland which has found expression into much of the islands’ poetry, music, and literature (Lima-Neves 2009). Thus, despite experiencing mass emigration for well over two centuries with peaks and troughs in emigration figures (Åkesson 2010; Carling 2004; Lopes and Lundy 2011; Åkesson and Baaz 2015; Graça 2013), the state has preserved durable connections with the emigrant communities, making it an interesting case-study for contextualizing the practice of external citizenship.

State Approaches to the Inclusion of Transnational Citizens: “Global Nation” Policies

Emigration states such as Cabo Verde are currently faced with an important dilemma: a significant proportion of their citizens are non-resident citizens or external citizens, often referred to as the “diaspora” (Cardoso 2012; Lopes and Lundy 2011; Graça 2013; Lima-Neves 2009). The relationship between states and citizens changes with emigration and as such emigration-states see their jurisdiction extended, albeit in a constrained manner, to the territory of the foreign sovereign states their citizens enter (Bauböck 2009; Lafleur 2015; Collyer 2013), therefore requiring a certain level of institutional re-organization.

Beyond the well-documented literature on remittances, states engage with external citizens based on a pre-existing relationship of rights and obligations. Given that external citizens for one reason or another have kept their citizenship of origin, through external citizenship, the state is able to tie potentially reluctant or increasingly distant (in time and space) populations abroad to their state of origin (Barry 2006; Gamlen 2008). This, for instance, is the case for Brazil, which conceptualizes voting as a civil duty of adult and capable citizens and extends this obligation to emigrants. If emigrants fail to vote, they can be penalized through the payment of fines and also face difficulties in terms of renewing travel documents. (Calderón-Chelius 2007).

As a theoretical framework, transnationalism (Bauböck 2003 & 2007; Bauböck and Faist 2010; Itzigsohn 2000) offers tools to acknowledge the agency of states to “claim back” or “make emigrants their own” (Gamlen 2008) by not discriminating between external and local citizens. Contrary to suggestions in the literature that emigrant states often engage with emigrant communities to fulfil the interests of political elites (Hampshire 2013; Lafleur 2011; Gamlen 2006), the “claiming back” in his context is conceptualized as integrating often marginalized citizens who are thus able to maintain a sense of belonging through external citizenship, rather than to control and manipulate them. Considering that research has shown that often immigrants face discrimination, racism, and marginalization (Lafleur 2005; Ashutosh 2013; Anderson 2013; Brader, Valentino, and Suhay 2008; Sargent and Larchanche 2007; Statham and Geddes 2006), the recognition of external citizenship grants a sense of social justice and fairness by providing space for the inclusion of external citizens, particularly important in an increasingly mobile and globalized world.

Legal Framework and Overview of Electoral Legislation

The Republic of Cabo Verde has several institutions, agencies, and organizations that deal with questions related to the political and economic integration of external citizens. Defining itself as a “global nation” (Graça 2013; Bauböck and Faist 2010; Waterbury 2010), the state implements a conjuncture of “global nation policies,” (Graça 2013; Meintel 2002; Collyer 2013) resulting on attention being directed towards the maintenance and consolidation of links with extraterritorial communities aiming for an increased approximation and participation of members of the diaspora with the archipelago.

The Ministry of Emigrant Communities has the duty to coordinate institutions and agencies that deal with the implications of emigration. The Ministry of Justice has the authority to attribute Cabo Verdean citizenship under the provisions of the Constitution, which has emigrant specific provisions. Article 7 (g) of the Constitution (República de Cabo Verde 1999) states that one of the fundamental duties of the state is: “to support the Cabo Verdean community dispersed around the world and promote the preservation and development of the Cabo Verdean culture within these communities.” The government is therefore under a legal obligation to support the emigrant community. However, the circumstances in which this support can be required are not specified.

Article 22 (2) (República de Cabo Verde, 1999) explicitly mentions that emigrants are citizens in their full right: “the Cabo-Verdean citizens who reside or find themselves abroad benefit from rights, freedoms and guarantees and are subjected to the duties established constitutionally which are not incompatible with their absence from the country.” Article 5 of the constitution (República de Cabo Verde 1999) establishes the right of Cabo Verdean citizens to dual citizenship.

Another important legal instrument is the Nationality Law, which presents two innovations. First, Article 8 extends the right to nationality in two occasions: to an individual born abroad whose 1) father or mother or 2) grandfather and grandmother are Cabo Verdean nationals by birth. This means that, on the one hand it grants nationality to the children of at least one emigrant parent, the so-called “second-generation” and, on the other extends it to the grand-children of two Cabo Verdean nationals, the so-called “third-generation.” Through this legislation, emigrants and their descendants saw their de jure condition of plural citizens protected whilst being able to simultaneously practice different aspects of political transnationalism (Meintel 2002; Lafleur 2005; Boccagni et al 2016).

Emigrants can vote for both legislative and presidential elections. The conditions for external voting are as follow: 1) must have emigrated from Cabo Verde no more than five years prior to the date of the beginning registration period; or 2) be the parents of and providing for a child or children under the age of eighteen or disabled, or are a spouse or older relative habitually residing in the national territory at the beginning of the registration period; 3) be serving a state commission or a public service position recognized as such by the competent authority, or residing outside the national territory as the spouse of a person in that position; or 4) if resident abroad for more than five years, they must have visited Cabo Verde within the past three years (Silva and Chantre 2007).

The electoral code makes a formal distinction between temporary emigrants (i.e., those who have emigrated no more than five years prior to the beginning of the registration period) and long-term emigrants, permanent emigrants, and members of the diaspora (i.e., those who have been abroad for more than five years). It does not, however, include any additional requirements for citizens to prove their bond to the national territory (Silva and Chantre, 2007). Cabo Verdean citizenship is sufficient, and according to Article 6 of the Electoral Code,5 entitlement is not affected by dual or multiple citizenship. It is therefore clear that lawmakers wanted to ensure that all citizens who maintain a bond with the country are entitled to vote.

For the presidential elections, given the potentially significant number of emigrant votes, there was a concern from the beginning to prevent the possible dominance of absent citizens in the political process (Silva and Chantre 2007; Brooke 1989). Therefore, it was decided that a system of weighting was required. As a result, each non-resident citizen is entitled to one vote, but those votes cannot not amount to more than one-fifth at most of the total votes counted in the national territory (Hartmann 2015). If this threshold is met, the votes are converted into a number equal to that limit and the number of votes cast abroad for each candidate are adjusted proportionately. The system is designed to avoid the potential dominance of non-resident voters given that the number of extra-territorial representatives is not proportionate to the number of registered non-resident voters. As a person being interviewed by The New York Times admitted, there would be a risk of Cabo Verde being run by the diaspora in the U.S., in view of sheer number (Brooke 1989).

External citizens can stand for election to the National Assembly, but not for presidential elections. Candidates in the presidential elections must have been residents within the national territory for three years prior to the election and cannot have dual or multiple nationalities. Arguably the most remarkable feature of the Cabo Verdean model of external citizenship is the extra-territorial political representation through the allocation of extra-territorial seats to represent external citizens in the legislature. The system provides six out of seventy-two representatives for the external citizens. The extra-territorial seats correspond to three constituencies: Africa, the Americas and Europe, and the rest of the world, with two representatives for each constituency. Cabo Verde has the highest percentage per total seats of seats allocated to extra-territorial constituencies in the PALOP6 (Table 1).

Table 1: List of Lusophone African countries and their respective position in terms of extra-territorial representation

| N. | Country | Extraterritorial seats | Total Seats | Extra-territorial Seats as % of Total |

| 1 | Angola7 | 3 seats (1 constituency) | 220 | 1.40% |

| 2 | Cabo Verde | 6 seats (3 constituencies) | 72 | 8.30% |

| 3 | Guinea-Bissau8 | 2 seats (2 constituencies) | 102 | 1.96% |

| 4 | Mozambique | 2 (2 constituencies) | 250 | 0.80% |

| 5 | São Tomé e Príncipe9 | 0 | 55 | - |

Source: Author’s compilation

All Lusophone African countries (Table 1), except for São Tomé and Príncipe, have provisions in place for extra-territorial representation (Hartmann 2015; Marques and Góis 2013). Nonetheless, the allocation for diaspora parliamentary representation in Cabo Verde is significantly higher than in other countries, attesting to the nation’s historically demonstrated active agency in redefining its territorial conceptions and political system to incorporate external citizens in the polis.

Practicing External Citizenship: The Cabo-Verdean Experience of External Voting

Despite efforts to include and represent the diaspora in the local polity, voter turnout remains low. A myriad of reasons can justify the low turnout of external citizens. For instance, states may grant the right to external vote in theory but then in practice resist polling methods that would facilitate the practice. Some states may also have limited capacity to reach out to increasingly dispersed emigrant communities, resulting in low numbers of registered voters. Therefore, there may be a gap between the theoretical form of membership (access to citizenship rights) and its substantive content (“practicing citizenship”) (Gamlen 2006; Østergaard-Nielsen 2003).

The Cabo Verdean electoral code states that registration to vote is compulsory and for external citizens it can take place all year around, instead of exclusively between the months of June and July, as it is for resident citizens. The analysis of the legislative elections follows the official distribution of the diaspora according to the three distinct extra-territorial constituencies.

Table 2: Voting turnout and abstention of the Africa constituency calculated for every election

| Year of Election | Registered Voters | N. Voters | Turnout (%) | Abstention (%) |

| 1991 | 2,976 | 1,557 | 52% | 48% |

| 1995 | 4,414 | 2,946 | 63% | 37% |

| 2001 | 5,702 | 2,480 | 43% | 57% |

| 2006 | 8,475 | 5,063 | 60% | 40% |

| 2011 | 4,196 | 2,983 | 71% | 29% |

| 2016 | 5,919 | 3,191 | 54% | 46% |

Source: Author’s compilation based upon data available on the website of the National Electoral Commission: https://cne.cv/

As an extra-territorial constituency, Africa represents citizens in countries in the other PALOP, as well as in Senegal. It presents interesting dynamics of external voting, as turnout has been consistently above fifty percent, except for the elections in 2001 (Table 2), showing that there is a clear commitment to remain engaged. The number of registered voters grew steadily until 2011, when it dropped to less than half, from 8,475 in 2006 to 4,196 in 2011. It is not clear why there was such a drastic drop in the number of registered voters. Despite this decline, the 2011 election was the year of the highest turnout of all time, for the African constituency at 71%, further emphasizing the volatility of voter turnout.

The relatively low numbers of Cabo Verdeans migrating to African countries imply that perhaps the Africa constituency might be the one with the most representative of-albeit far from perfect-the total number of registered voters. However, it also has its own specific challenges in terms of practicing external citizenship due to some socio-economic constrains faced by citizens. As such, if citizens live in rural São Tomé e Principe, rural Guinea-Bissau, or Mozambique, they might register to vote if they do not possess a second citizenship, because it is compulsory. However, they might in turn be impeded to participate due to socio-economic limitations which affect their ability to travel for instance. Such factors reduce the hypothesis of examining the prevalence of their desire to stay engaged in the politics of the home-country.

Table 3: Voting turnout and abstention of the Europe and the rest of the world constituency calculated for every election

| Year of Election | Registered Voters | N. Voters | Turnout (%) | Abstention (%) |

| 1991 | 2,997 | 965 | 32% | 68% |

| 1995 | 10,114 | 2,482 | 25% | 75% |

| 2001 | 14,182 | 2,260 | 16% | 84% |

| 2006 | 31,677 | 26,775 | 85% | 15% |

| 2011 | 22,157 | 11,492 | 52% | 48% |

| 2016 | 28,832 | 8,128 | 28% | 72% |

Source: Author’s own compilation using information from the National Electoral Commission of the Republic of Cabo Verde10

Europe and the rest of the world represents emigrant communities all over Europe in Portugal, France, Italy, Spain, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, as well in other parts of the world such as China (Macau), India, and Russia. It is the constituency with the highest number of registered voters. Firstly, because it covers “the rest of the world,” wherever Cabo Verdean emigrants happen to find themselves, meaning that it can incorporate a very large number of emigrants, and secondly, the European wave of migration is more recent and thus probably includes a significant number of first-generation emigrants.

Recent research on the engagement of second and third generations (Cardoso 2012; Cabral Alves 2015; Graça 2013) has demonstrated an emphasis on cultural aspects such as speaking the language, going on holiday, and keeping close contact with family members. There is however, a strong sense of identity and belonging as second- and third-generation individuals often admit to identifying as Cabo Verdean and taking the step to acquire the formal citizenship available to them (Cardoso 2012; Cabral Alves 2015; Lopes and Lundy 2011).

In 2006 (Table 3), the registered number of voters in this constituency accounted for almost 10% (31,677) of the total number of registered voters (322,767) (Table 5), with most of the registered voters choosing to exercise their right. This contributed to a turnout of 84.53%, well-above the national turnout of 46%. This illustrates that, through practiced external citizenship, non-resident citizens can effectively take part in civic participation and be part of the political community of the nation. Nonetheless, registrations to vote and turnout fluctuate quite substantially, going from only 16% in the 2001 election to the highest ever in 2006 at 85%.

Table 4: Voting turnout and abstention of the Americas constituency

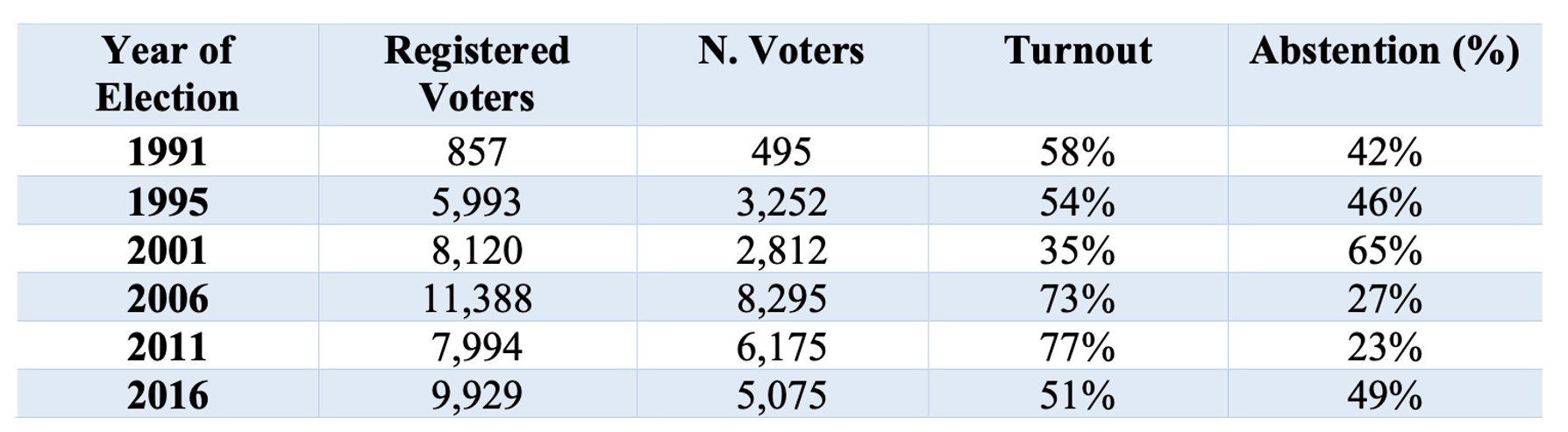

Source: Author’s compilation based upon data provided by the National Electoral Commission of the Republic of Cabo Verde; http://www.cne.cv

The Americas represent emigrant communities in the USA, Brazil, Argentina, and Cuba and include the oldest and best-established emigrant communities. The USA emigrant community has consistently maintained strong links with the archipelago and has traditionally shown interest in politics. It went from 857 registered voters in 1991 to 5,993 in 1995 (Table 4). While the number of registered voters declined in 2011 from 11,338 to 7,994, turnout remained high. It registered its lowest turnout in the 2001 elections (35%), but during the following election in 2006, it rose again to 73%.

Considering that the U.S. has a large third- and fourth-generation group of Cabo Verdeans (Andrade-Watkins 1987; 2015; Lima-Neves 2009; Lopes and Lundy 2011), the consistent and relatively high turnout is a positive sign of practicing external citizenship. However, considering that it is estimated that the U.S. has well over 300,000 Cabo Verdean emigrants (Lima-Neves 2009; Avelino Carvalho 2010; Andrade-Watkins 2015; Lopes and Lundy 2011), the significantly low numbers of registered voters appear to confirm the literature on the engagement of the second generation in home country politics (Lima-Neves 2009; Cabral Alves 2015; Graça 2013). Second and subsequent generations tend to be less interested in politics in countries they often perceive as merely being the country of origin of their parents or grandparents.

Table 5: Total number of registered voters for every election held in Cabo Verde

| Year of Election | Registered Voters | N. Voters | Turnout (%) | Abstention (%) |

| 1991 | 166,618 | 125,564 | 73% | 27% |

| 1995 | 207,618 | 158,901 | 77% | 33% |

| 2001 | 260,126 | 141,836 | 55% | 45% |

| 2006 | 322,767 | 147,937 | 46% | 54% |

| 2011 | 298,567 | 226,942 | 24% | 76% |

| 2016 | 347,622 | 229,337 | 66% | 34% |

Source: Author’s compilation based upon data provided by the National Electoral Commission of the Republic of Cabo Verde; http://www.cne.cv

In terms of the overall picture, in the 2006 election, all extraterritorial constituencies had a turnout of over 50%, which was superior to the national average of 46%. Both the “Americas” and “Europe and the rest of the world” constituencies registered an exceptional turnout of 72.84% and 84.53%, respectively, with the latter constituting almost double the national turnout. This raises important questions about the future of democracy in Cabo Verde and contributes to an important debate on the perceived deficit of democracy in the archipelago (Costa 2013; Varela and Lima 2014), resulting in people turning away from the exercise of democracy (Costa 2013; R. W. Lima 2017; Varela and Lima 2014; Lima 2012).

Does the Emigrant Vote Make a Difference?

Only thirteen countries in the world allocate extra-territorial constituencies representing emigrant communities, five in Africa (Algeria, Angola, Cabo Verde, Mozambique, and Tunisia), five in Europe (Croatia, Italy, France, Portugal, and Romania), and three in Latin America (Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama). Cabo Verde shares the top position with Tunisia11 of having the highest percentage of emigrant political representation in the legislative per total of representatives (8.3%). This is relevant because the actual weight of the representatives depends on the size of the assembly (Ellis et al 2007).

These provisions provide assurances that there is no risk of the emigrant vote dominating the legislative elections. External citizens vote for their own political representation in parliament, which serves as a reminder that although not physically present, emigrants are part of the nation. These seats are important because, unlike alternative tools to give voice to emigrants, such as consultative bodies, elected representatives for the extra-territorial constituencies have equal power in comparison to national representatives and are responsible exclusively for ensuring that emigrants have a voice in both the running of the country and the drafting of legislation (Lafleur 2013).

Despite the fact that in presidential elections all citizens are entitled to one vote, there has never been a single presidential election where expatriate citizens came close to reaching the limit imposed for external citizens (Hartmann 2015). Nonetheless, there were two presidential elections where a relatively small number of external voters reached what Bauböck and Faist (2010) called the “tipping scenario,” and were perceived to have determined the final outcome of the elections in a close electoral competition.

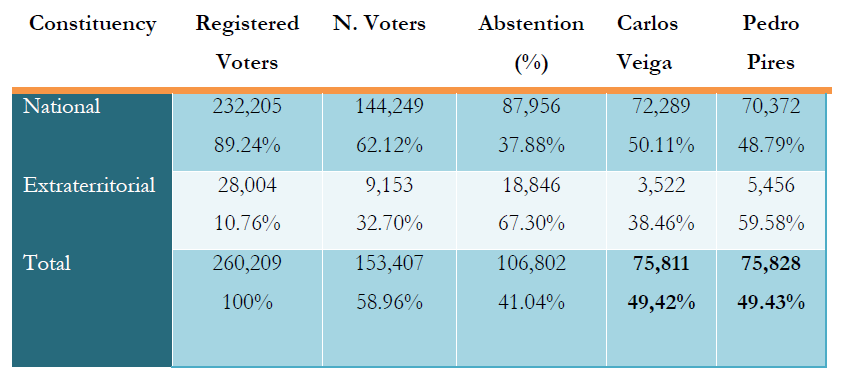

In the 2001 election, candidate Carlos Veiga won the election in the national territory with a total number of 72,289 votes (50.11%) of the total number of 144,249 votes (Table 6). However, the other candidate Pedro Pires, although only amassing 70,372 (48.79%) votes, managed to get 5,456 votes (59.58%) in the extra-territorial constituencies, making a total of 75,828 votes (49.43%) and therefore winning the 2001 election by a decimal percentage-point due to the advantage of the “migrant vote.” Carlos Veiga only obtained 3,522 (38.46%) of the total votes in the diaspora, giving him a total of 75,811 votes (49,42%).

Table 6: Results for the two main candidates of the 2001 election

Source: Author’s compilation based upon data provided by the National Electoral Commission of the Republic of Cabo Verde; http://www.cne.cv

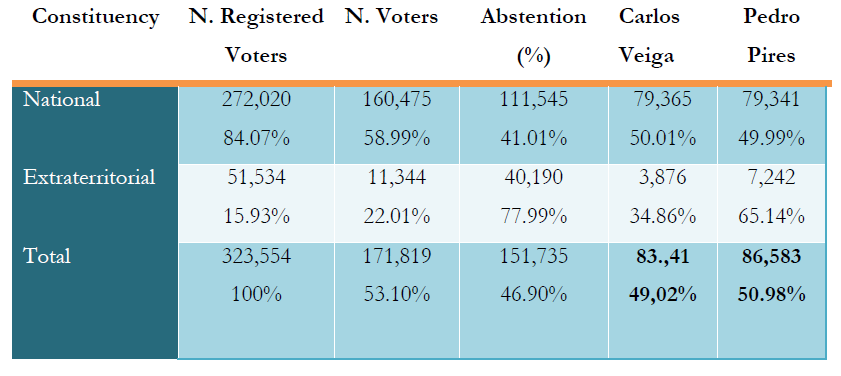

Curiously, the same situation was repeated in the 2006 presidential elections which featured the same candidates (Table 7). Candidate Pedro Pires obtained only 49.99% of the total votes, against the 50.01% obtained by the candidate Carlos Veiga in the national constituencies. However, he obtained 65.14% of the votes in the extra-territorial constituencies, against the 34.86% of the votes obtained by candidate Carlos Veiga. Consequently, the candidate Pedro Pires was able to secure an overall majority of 50.98% against the 49.02% obtained by Carlos Veiga, thus winning again the presidential elections by a very small margin.

The “emigrant advantage” through the so-called “emigrant vote” was not at all contested at the national level, neither by candidates, nor by the resident citizens. This reflects a broad social consensus within Cabo Verde that emigrants are part of the national landscape thus encouraged to participate in the polity. This scenario supports the literature illustrating that “a candidate who carries his or her electoral campaign abroad challenges the traditional assumption that domestic politics are exclusively decided within the internal arenas of the nation-state” (Bauböck 2003a: 702). Furthermore, the fact that in both the 2011 and 2016 presidential elections, the fact that the candidate who won, José Carlos Fonseca, was himself a returnee emigrant who worked in Portugal between 1982 and 1990, illustrates that the Cabo Verdean society recognizes not only the political integration of the emigrant communities expressed through their right to vote in elections, but also their right to be candidates to represent the nation.

Table 7: Results for the two main candidates of the 2006 election

Source: Author’s compilation based upon data provided by the National Electoral Commission of the Republic of Cabo Verde; http://www.cne.cv

Through their practice of external citizenship, Cabo Verdean emigrants, diaspora, and the state effectively challenge territorially bounded notions of the nation-state by showing that the decision to live beyond the territorial boundaries of a nation-state does not imply severing ties with it. On the contrary, practices of external citizenship manifested through external voting illustrate that in an increasingly mobile and globalized world where individuals are no longer tied to their countries of birth or residence, and indeed might hold multiple citizenships, territorially bounded notions of a nation and its people have become a thing of the past.

Conclusions

The Cabo Verdean government has been consistent in considering the emigrant communities as an essential part of the state’s political community. It has sought to maintain external citizens engaged and relevant to the country and it has achieved this feat mainly by providing for the representation of diasporic citizens in parliament. It can be argued that through the joint initiative of the state and the agency of emigrant communities, the borders and boundaries of the Cabo Verdean state are redefined to include what is often referred to as the eleventh island, the diaspora. The Cabo Verdean state has, therefore, successfully contested bounded notions of the nation-state, as indeed states across the globe becoming increasingly accustomed to doing (Ellis et al 2007).

Transnationalism challenges the notion that emigration states are not interested in engaging with their non-resident citizens beyond remittances. The Cabo Verdean case discussed here illustrates that emigrants can become “transmigrants” (Bauböck 2003). Whilst well integrated in their host societies, they remain linked to the home country through various transnational activities, including external voting. They achieve this by working within mechanisms that are put in place by the state to foster the continuous engagement of external citizens. What makes the Cabo Verdean case interesting and unique is the fact that, despite the relatively high turnout in overseas constituencies with a tangible impact on electoral results, this is not interpreted as challenging the future of democracy in the archipelago. This paper shows that the contrary is the case. The volition to include the diasporic vote while being open to the entire adult citizenry is illustrative of the way in which the diaspora has always been constructed in the political and social imaginary of the archipelago, namely, as forming part of the nation. This tallies with the literature on transnationalism and transnational political participation and mobilization which emphasizes the need to think beyond territorial borders.

The willingness of external citizens to engage with their home countries is further evidenced by the fact that at one point the “Europe and the rest of the world” constituency registered a turnout of almost 10% of the number of votes cast. Furthermore, the “emigrant vote” has proved decisive on two occasions (2001 and 2006 elections), changing the final result of the overall majority, thereby heightening the importance of their vote. Despite the relatively low turnout, the strength of external voting lies in the fact that it does not alienate citizens living abroad and that it includes those who, whatever their geographical location, decide to maintain a close bond with their country of origin. Cabo Verdean citizens have shown that they continue mobilizing identity and practicing citizenship (Soysal 2000) through a range of transnational practices; today’s generation of Cabo Verdean emigrants can be legitimately called “transmigrants” (Meintel 2002). They are better educated than their forebears, multilingual, and relatively well-connected to the ruling elite in Cabo Verde (Meintel 2002). Therefore, they stay informed about the political life on the islands and see engagement in politics as potentially positive upon their return (Meintel 2002).