Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Relações Internacionais (R:I)

versão impressa ISSN 1645-9199

Relações Internacionais no.esp2018 Lisboa 2018

https://doi.org/10.23906/ri2018.sia04

PORTUGAL AND EUROPE

The 2014 European electoral manifestos a preliminary analysis of the main competition dimensions*

Os programas eleitorais das europeias de 2014: uma análise preliminar das principais dimensões de competição

Jorge M. Fernandes* and José Santana-Pereira**

* Post doctoral researcher at the Instituto de Ciências Sociais of the Universidade de Lisboa. PhD in Social and Political Science from the European University Institute of Florence in 2013. His research interests are institutions, parties, electoral systems,and parliaments. His work has been published in Comparative Political Studies, European Journal of Political Research, Party Politics, among others. Co-editor of the book Iberian Legislatures in Comparative Perspective (Routledge). In 2018-2018, Visiting Scholar at Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University. jorge.fernandes@ics.ulisboa.pt

** Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science and Public Policy, ISCTE-IUL and Integrated Researcher at CIES-IUL. PhD in Social and Political Science from the European University Institute of Florence in 2012. His research has focused on the attitudes and political behavior of citizens from a comparative perspective, the role of the media in developing and changing these attitudes, the differences between European media systems and the the attitudes of parties and public opinion towards the European Union. jose.santana.pereira@iscte-iul.pt

ABSTRACT

The European project has enjoyed considerable support from both elite and masses in Portugal. Since the country joined the EEC in 1986, the main political parties have been strong supporters of the Europe project. In recent years, however, this has been undermined by both political and economic crises. In this paper, we produce a preliminary analysis of the competition dimensions in the forthcoming 2014 European elections. We make an empirical analysis of the position held by the five most important Portuguese political parties in relation to European integration, the Euro, debt renegotiation, Eurobonds, and changes in pensions in a context that fosters contestation of European integration and its outputs.

Keywords: European Election, Electoral Manifestos, Euro, Economic Crisis.

RESUMO

Em Portugal, a opinião pública e as elites têm dado um apoio constante ao projeto europeu. Desde a entrada de Portugal na CEE, em 1986, os principais partidos políticos foram fortes apoiantes da Europa. Nos últimos anos, porém, a crise económica e política tem vindo a erodir o apoio ao projeto europeu. Este trabalho faz uma análise preliminar das principais dimensões de competição das eleições europeias de 2014, analisando o posicionamento dos cinco maiores partidos portugueses em relação à integração europeia, ao euro, à renegociação da dívida, aos eurobonds, e aos cortes nas pensões, num contexto favorável à contestação da integração europeia e dos seus resultados.

Palavras-Chave: Eleições Europeias, Programas Eleitorais, Euro, Crise.

INTRODUCTION

The crisis triggered by the financial crash in Europe exposed many of the weaknesses in the European construction process, notably with regard to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)1. The crisis, which began in 2008, had enormous political repercussions including that of the foreseeable punishment of incumbents with successive election defeats of governments in Portugal, Spain, Greece, Iceland and Italy2. In the countries most affected by the European crisis, such as Greece, there has even been a reconfiguration of the party systems due to the abrupt fall of traditional parties (PASOK) and the appearance of extremist parties like SYRIZA and Golden Dawn3.

In Portugal, the European elections on 25th May 2014 will take place in a context of great economic, political and social tension, largely as a result of the austerity measures implemented by the Socialist Party (PS) (led by José Sócrates), and the Social Democratic Party (PSD/CDS-PP) (led by Pedro Passos Coelho), notably after the signing of the agreement with the troika (International Monetary Fund, European Commission and European Central Bank). The Portuguese – supporters of the European project since the country’s adhesion to the EEC4 – are extremely disappointed with Europe. Eurobarometer data from autumn 20135 show that 79 per cent of the Portuguese feel that the European Union (EU) does not listen to them. Only a fifth of those surveyed believe that the EU has a positive image and that Europe is moving in the right direction. Moreover, Portuguese citizens are divided with regard to the Monetary Union and the Euro, with only 20 percent believing that the economic and financial crisis can be resolved at the European level. Thus, the Portuguese were unhappy with the European project, which seemed to have failed to generate prosperity and economic security. They are also pessimistic about the way in which democracy functions in Portugal (85 percent said they are dissatisfied) and they unanimously describe the state of the economy as disastrous, which, according to research on the economic vote, tends to be reflected in bad election results for the governing parties6.

Which electoral strategy will Portugal’s main political parties choose, notably those that led the country’s accession and integration process into the EU, during the 2014 European election in light of this apparently unfavourable context for a strong pro-European discourse where European matters are interwoven with the decisive subject of the economic situation more than in any other European elections in Portugal to date (largely due to the direct intervention of European institutions in managing the problem of the Portuguese sovereign debt)? The present article is a first systematic approach to this question as it analyses the electoral manifestos prepared by the parties/coalitions represented in the European Parliament (Portugal Alliance (Aliança Portugal), Left Bloc (Bloco de Esquerda), CDU and the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista)) during the first months of the year. The aim is to identify the positioning of Portugal’s main political forces on the five major topics linked to Europe and the economic crisis, and to shed light on the impact of factors such as political ideology, their government situation (incumbent/opposition) and party type (mainstream or more radical) in the positions expressed in their electoral manifestos.

In the following pages, we will briefly describe the main patterns in the positioning of Portuguese political parties in relation to Europe, as indicated in the programmes prepared during the campaigns for these second-order elections7. After presenting the hypotheses, data and dimensions of the analysis, a content analysis of the electoral manifestos of the Portuguese parties is used to analyse their positioning. The main patterns observed will then be discussed in light of the current social and political context.

CONTENT OF THE PORTUGUESE PARTIES’ ELECTORAL MANIFESTOS FOR THE EUROPEAN ELECTIONS

European elections directly elect citizens’ representatives in the European Parliament. They were first held in 1979 and have since taken place every five years. Reif and Schmitt refer to the European elections as second-order national elections; indeed, they can be compared to local or regional elections given that they have no direct impact on the governance of the national public territory. According to these authors, the European elections are dominated by the national cleavages (insofar as the European ‘arena’ is abstract, distant and not very politicised); they are characterised by higher abstention rates than first-order elections (i.e. legislative elections, in the Portuguese case), as well as by better election perspectives for small and/or new parties and a tendency to penalise the governing party8. European elections in Portugal have undoubtedly been second-order elections, given the high abstention rates (higher than the European average irrespective of their timing in the national political calendar), and the fact that both the bigger and governing parties have less satisfactory results than the opposition and/or smaller parties9.

The fact that European elections are seen as second-order national elections also has implications for the presence of European matters in campaigns. European elections are often an arena to discuss matters of national relevance at the expense of truly European issues. This phenomenon is frequently seen in the media, thanks not only to editors and journalists but also the political actors involved in the campaigns10. The presence of European subjects in more visible political campaign materials, such as airtime or posters, is limited to the point that the expression «Europe-shaped hole» can be used to describe its content: in 2009, three quarters of the campaign materials prepared by the Portuguese political parties represented in the European Parliament addressed national matters11. In this case, there is a marked cleavage between governing and opposition parties, with the incumbent dedicating two thirds of their political communication material to European issues while the opposition parties tend to address Europe much less.

The amount of attention given to European matters in the parties’ electoral manifestos is determined by factors such as the level of politicisation of European subjects at the national level, or the level of intra-party disagreement on Europe12. In the Portuguese case, the political parties’ positions and preferences on the European project can usually be clearly identified in their euromanifestos. The analysis of the documents prepared for the European campaigns in the first 23 years of Portugal’s membership of the EEC/EU reveals three major phases in Portuguese political parties’ attitudes towards Europe13. The first phase, from 1986 to 1991, is one of widespread enthusiasm and specific pragmatism, insofar as the main parties (with the exception of the CDU) evaluated adhesion positively, albeit with a certain scepticism regarding the concession of some decision-making powers to the EEC. In the second phase, which ran from the Maastricht Treaty to the turning of the millennium, we see the governing parties’ increased enthusiasm about the European project but also the appearance of a real cleavage between large and small parties on Europe-related matters; this followed a change in the CDS leadership when it adopted a clearly Eurosceptic position on the grounds that it was defending the national identity and sovereignty14. The third phase, from 2000 to 2009, ran parallel with the growth in the Left Bloc’s electoral success, as well as the EU’s enlargement to the East. This phase is marked by some dispersed scepticism (with the increased presence of references to some negative or contradictory aspects of EEC/EU adhesion in electoral manifestos) in relation to the support for the European project specifically, notably in the attempt to give Europe a greater role and more power in decision-making processes and the management of areas like the environment, immigration, justice, and social policies15.

Despite these broad trends, the positions of the Portuguese political parties have varied considerably. Sanches and Santana-Pereira tested the impact of three of the parties’ characteristics using the positions expressed in the European electoral manifestos published between 1987 and 200416. Following Hooghe, Marks and Wilson17, the first two variables address ideology and ideological extremism (distinguishing between right and left-wing parties, and between parties towards the centre with diffuse ideologies and extreme parties). The third variable was related to the party’s situation at the time of the European elections, and made the distinction between the parties with governing responsibilities and opposition parties. The analysis showed that the left-right cleavage was relatively unimportant: indeed, the PS has always been closer to the PSD than to the CDU on the European project. In general terms, political competition on the subject of European affairs seems to have been based on the cleavage between the so-called ‘centrist’ parties and small parties that are ideologically more defined. This was the case particularly in the 1990s, when the CDS took a much more Eurosceptic stand than it does today, thus joining forces with the traditionally critical CDU. Although the PS and the PSD have been clearly pro-Europe, it should be noted that they tend to be less enthusiastic supporters when they are in the opposition18.

There are clearly electoral reasons for the oscillations in the declared positions of some Portuguese political parties on the EU. In an attempt to obtain the best election results possible, parties seek to control the tensions between the positions previously expressed, public opinion at the time of the elections, and the political measures implemented by the government in a multi-level governance system. Although Portugal’s European integration was essentially led by the elite, with little participation or intervention by the people and civil society19, the attitudes to Europe in the public opinion have never been irrelevant; in fact, the high level of support for the European project enabled the governing parties to make electoral gains thanks to the advantageous consequences of Portugal’s adhesion to the EEC/EU20. This is the main reason why, from 1986 to 2009, the governing parties’ positions on Europe tended to be very positive and receptive to the further development of the Union21. Marina Costa Lobo reached a similar conclusion when analysing the salience given to the subject of Europe in the political programmes of Portuguese parties, noting that it «varies depending on each party’s circumstances at a given election. In other words, the subject of Europe and the positioning for or against are highlighted or downplayed according to whether or not the parties believe they contribute to their goals at a given electoral moment»22.

OBJECTIVES, HYPOTHESES, DIMENSIONS OF ANALYSIS, AND MATERIALS ANALYSED

This paper analyses the positioning of the Portuguese political parties in the forthcoming 2014 European elections on important dimensions of the political competition during the campaign period, with the aim of identifying the main patterns and some of the factors that structure and shape the parties’ position. The positioning of each party is identified by analysing the content of the electoral manifestos produced for the European elections. This method of positioning parties as per ideology has a long tradition in political science; it is considered more reliable and is used more frequently than other methods (use of data collected by expert surveys or public opinion polls) due to its objectivity and impartiality and the great availability of data23. Given the objectives of this article, electoral programmes (or similar party documents) are undoubtedly the most suitable choice given that a truly systematic analysis of the political parties’ positions on the crisis, Europe and the interconnection of these two subject areas must be analysed based on official documentation, particularly if it has been prepared with electoral objectives in mind.

The analysis of the electoral programmes covers only the four political parties and coalitions already represented in the European Parliament. We therefore chose to focus on the parties with a formalised and institutionalised relationship with Europe as a result of their recent presence in successive Parliaments: PS, PSD, CDS-PP, BE and CDU. The Socialist Party (PS) chose its leader and Member of the European Parliament (MEP) between 1999 and 2004 to head the party list. The governing parties (PSD and CDS-PP) announced the formation of the Portugal Alliance coalition in March 2014, with the Member of European Parliament, Paulo Rangel, heading its list. Two names connected to the CDS-PP (Nuno Melo, MEP, and Ana Clara Birrento, professor and member of the party) were among the coalition’s first ten candidates. To the left, the smaller parties with parliamentary representation chose two young figures who had already proved themselves in the European Parliament: Marisa Matias (Left Bloc) and João Ferreira (CDU). In terms of the people involved in the campaign, the focus seems to have been essentially on continuity.

Based on the results of studies on the positions on the EU of Portugal’s political parties in electoral programmes published in the last few decades24, the parties are again expected to seek a balance in 2014 between their traditional position on Europe and the opportunities and constraints afforded by the current context, both from the point of view of the climate of public opinion (waning enthusiasm for the European project, apprehension due to the intervention of European institutions in the country’s economic and financial management), and in terms of their current position vis-à-vis the government (incumbents vs. opposition parties). Thus, Portugal Alliance25 is expected to express enthusiasm for the European project and to defend the measures that result directly or indirectly from the agreement made with the troika (hypothesis 1), while the Socialist Party, which traditionally defends the European Union, will tend to align its Euro-enthusiasm with some scepticism about the measures implemented by the government to resolve the debt problem (hypothesis 2). CDU benefits from a fruitful terrain to express its traditional positions, and will therefore continue to stress its mistrust of the EU (hypothesis 3). Lastly, the BE, the Euro-enthusiasts with nuances26 and with a more recent representation in the European Parliament, can choose to ride the wave of discontent with the government and the EU and, like the Communists and the Green Party (Verdes), highlight its criticisms of the EU in its 2014 electoral programme (hypothesis 4). Accordingly, the government parties vs. parties with no governing experience dichotomy is expected to be associated with major differences in terms of the positions on Europe, and explicit support for the European project is therefore more likely to be found among the former than the latter (hypothesis 5).

In light of the necessary brevity of this study, we have decided to focus our analysis on five fundamental dimensions. The choice was governed mainly by the centrality and salience acquired since the onset of the crisis in Portugal, particularly in relation to economic and financial policies – a subject that is now inextricably linked with European matters. We seek to understand where the Portuguese parties stand on the following topics:

- General attitude on the European Union.

- Need to renegotiate the Portuguese debt.

- Remaining in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).

- Mutualisation of European States' debts, with the creation of Eurobonds.

- Permanent cuts to pensions and benefits.

All the dimensions are directly or indirectly related to the EU in that they involve matters directly linked to the EU and its institutions, or in which the latter have played an important role. These dimensions capture each party’s overall position on European integration (i), public debt (ii), a subject of great salience since the beginning of the assistance programme, and on the EMU (iii; iv). Dimension number v was included as it has become of increasing salience in recent years, and is absolutely central in the May 2014 European elections, and due to the fact that these measures have been presented and discussed as part of the adjustment process required under the agreement with the European institutions and the IMF.

The party documents27 used in this article are as follows: the electoral manifest entitled «Portugal Alliance – Europeans 2014», published in March 201428, was mostly used for the PSD-CDS coalition. The electoral programme presented by the coalition stands out mostly because of its unique format: 101 ideas tweeted to facilitate the dissemination of the party’s positions and proposals through social networks29. We also used the programme of the 9th Constitutional Government30. Several sources31 were used for the Socialist Party, namely the October 2010 Declaration of Principles (Declaração de Princípios de outubro de 2010)32, the 2011 legislative elections programme33, the Portugal Has a Future (‘Portugal Tem Futuro’) motion34, and the New Direction for Portugal (‘Novo Rumo para Portugal’) declaration35. For the CDU, we used the 2014 European election manifesto entitled «Portugal with a Future in a Europe of the Workers and the People» (‘Um Portugal com Futuro numa Europa dos Trabalhadores e dos Povos’)36. Lastly, in the case of the BE, we used the manifesto Disobeying a Europe of Austerity (‘Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade’)37, prepared by the party for the May 2014 European elections.

ANALYSING THE COMPETITION DIMENSIONS

Let us start by analysing the Portuguese political parties’ positions on European integration. As we have seen, historically the main parties in the Portuguese party system (PS and PSD) have been strongly pro-European. The other parties are known for their marked scepticism (CDU) or, as in the case of the CDS, of shifting between Euro-scepticism and being pro-European38.

In the 2014 European elections, the government’s coalition parties (PSD and CDS-PP) have stated that they are strongly in favour of the European project; their Portugal Alliance manifesto states that «we are part of the European future and today we are full citizens of Portugal and Europe»39. The PS, in its 2010 Declaration of Principles, reaffirms that it is «totally in favour of the European construction process, and in favour of the development, strengthening and enlargement of the European Union»40. In line with the CDU’s traditional scepticism but without ever explicitly affirming its opposition to the European project, its manifesto for the 2014 European elections argues that «nothing can force Portugal to agree to the subordination of the State within the EU framework or to divest its national sovereignty and independence»41. The CDU also manifests its opposition to the Budget Treaty, a recently-created instrument to maintain the strict rules of budgetary control, namely holding the structural deficit at 0.5%. This coalition’s position is clear; it defends the «reversibility of agreements and treaties that rule the current integration, starting with the Lisbon Treaty, the Budget Treaty, and the legal documents on Economic Governance»42. There are some nuances in the Left Bloc’s position. On one hand, it presents itself as an integral part of the pro-Europe left as opposed to the Euro-sceptic left, but on the other it clearly rejects the current distribution of power, and proposes fighting for the refoundation of the EU’s institutions. According to the BE electoral manifesto, «the European left parties must have a project for the refoundation of Europe (...) that will overcome the institutional blockage created by unbending treaties»43. The document also states that the BE defends a «referendum on the Budget Treaty in which the voices of the victims of this policy will oppose this broad institutional consensus»44.

An analysis of the parties’ position on renegotiating the public debt (dimension 2) reveals a cleavage between the government parties and the opposition. The government parties defend that «decreasing the Portuguese economy’s excessive debt must be achieved (by) steadily reducing public debt»45. More explicitly, they add that «Portugal must comply with its commitments. Although not easy, it is indispensable»46. In a diametrically opposed position, the motion ‘Portugal Has a Future’ from the PS, the largest opposition party, not only foresees «a renegotiation of the extension of the payment deadlines for part of the public debt» but also the «renegotiation of the interest to be paid on loans obtained»47. The CDU and the BE’s positions are quite similar, with both parties defending that Portugal should immediately renegotiate the amounts, deadlines, and interest on public debt.

The third dimension analysed herein seeks to understand the political parties’ specific position on the single currency. Remaining in the EMU has been a topic of increasing salience in recent years. Generally speaking, the idea of leaving the single currency (still) seems to be considered undesirable in Portugal. However, some striking differences between the political parties are worthy of note. In its manifesto, the Portugal Alliance defends that «Portugal must consciously choose a single currency that will serve its interests and allow the economy to grow steadily»48. According to the governing parties, this entails «an institutional reform of the Economic and Monetary Union (...) so that integration is strengthened responsibly and with solidarity, shared powers and guarantee mechanisms»49. The PS, on the other hand, clearly states in its ‘New Direction for Portugal’ declaration that «the choice is not between staying in or leaving the Euro. For us, the urgency is in changing the Euro Zone and completing it with political, economic and social governance»50. Indeed, it should be noted that the three parties that have shared governing roles in Portugal since democratisation not only agree Portugal should remain in the euro, but also that institutional reforms are required to correct the EMU’s shortcomings. While the BE has never explicitly come out in favour of Portugal remaining in the euro area, it does, however, reject «more sacrifices in the name of the Euro»51. We can therefore assume that the BE defends Portugal’s continuation in the euro area must be compatible with the end of austerity and sacrifice. Marisa Matias, who heads the party list, confirmed this when she said «if we reach a point where we have to choose between the euro area and the welfare state, I have no doubt that we will have to choose the welfare state»52. The CDU is the most openly euro-sceptic party in this dimension of our analysis. In its electoral manifesto, the coalition states that Portugal must fight to «dissolve the Economic and Monetary Union and adopt measures that prepare the country for any changes to the euro area, namely those resulting from Portugal’s exit, whether of its own accord or due to future developments of the EU crisis»53. The analysis of this dimension reveals the stark differences between the PSD-CDS coalition and the PS on one hand, and the positions defended by the BE and the CDU, which differ in terms of intensity. Whilst the former are adamant that Portugal should remain in the EMU and must strive for the necessary institutional reforms that will ensure the Euro is in keeping with the end of austerity, the other parties believe that leaving the Euro is, or may become, a reality. If the economic and social costs of austerity continue to rise, Portugal must consider leaving the euro area.

The fourth dimension analysed herein is the position of Portuguese political parties on Eurobonds, an instrument many see as being part of the above mentioned institutional reforms of the EMU. Yet again, the cleavage between the more pro-Europe parties and the much more Eurosceptic party in the Portuguese partisan system is evident. The PSD and the CDS-PP, as well as the PS and the BE, are in favour of the creation of debt mutualisation mechanisms. In its electoral manifesto, PSD and CDS-PP clearly state that «the future development of solidarity and debt mutualisation mechanisms is desirable (...). To that end, the Union must optimise structural reforms in the Member States by means of a system of ‘contractual arrangements’ and ‘associated solidarity mechanisms’ mutually agreed upon by the Member States and the European Union»54. Similarly, the PS highlights the «need to focus on economic growth, as well as the introduction of Eurobonds at a European level so as to mutualise the debt of the euro area countries»55. In this dimension, the BE takes a similar position to that of the coalition parties and the PS. In their 2014 manifesto, the BE argue that the «EU must have its own debt management instruments that can serve as a resource for Member States, but benefiting from the funding costs that an area like the EU can provide»56. In keeping with its usual Euroscepticism, the CDU is the only Portuguese political player openly against any debt mutualisation mechanisms. In a recently approved thesis, the Communists call this type of mechanism a «decoy», characterising it as «a speculative fund built on the Member States’ contribution to increase sovereign debts and the dependence on large financial capital»57.

Lastly, we turn to the question of pensions and the future of the public Social Security, a subject widely debated in Portuguese society. This dimension is particularly important in the context of European elections as the successive updates to the memorandum of understanding have included key measures in this area of governance. In the months immediately prior to the European elections, the topic of a permanent cut in pensions has been acquiring growing salience. In the government programme, the PSD and CDS-PP states that «it is necessary to study and assess the introduction of reforms that introduce a savings component in the old-age pensions whilst maintaining the State’s guarantee in the area of compulsory solidarity»58. The PSD and the CDS-PP justify this measure with the «fall in the economic dependence ratio» and the «progressive maturation of careers»59. On the other hand, the proposal from the PS is based on the reform implemented by the José Sócrates government in 2006. The Socialists therefore defend «promoting the sustainability, efficiency and equity of public Social Security without overlooking the conjunctural financial restrictions, but as an alternative to the project of the Portuguese right-wing to partially privatise and slim down Social Security». The CDU and BE have very similar positions on Social Security. They both defend that the public system should be maintained and plainly reject the «pension and benefits devaluation» policy.

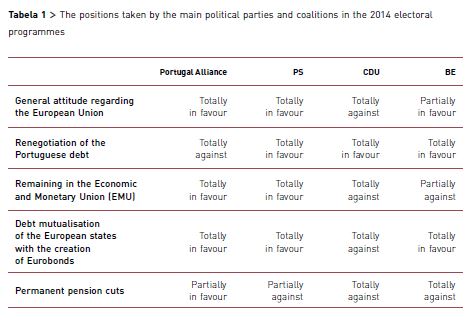

Table 1 systematises the positions of political parties on the five dimensions under analysis, using a scale that ranges from totally in favour, to partially in favour, partially against, and totally against. The PS and the Portugal Alliance continue to present themselves as political parties in favour of European integration, expressing general support for the European project, remaining in the Euro zone, and debt mutualisation by creating Eurobonds. The main sources of disagreement between these two leading players in the 2014 European elections are the need to renegotiate the debt (defended by the Socialists but rejected by the governing parties) and making permanent cuts to pensions and benefits; this measure was proposed by the government with a few nuances and partially refuted by the main opposition party. Thus, these positions are in line with the past of the PSD and PS, in which they stand out as the main players in the European adhesion and integration processes, and with the position of the PS as the main opposition party.

CDU’s strong nationalist and Eurosceptical position, identified in most of the programmes published for European elections in the last 30 years60, is still present in the 2014 documents. On the other hand, the BE position is somewhat undefined and with several undertones, which sets it apart from the strongly Eurosceptic CDU and the centrist parties. Thus, only the hypothesis on the BE position in the electoral programme for the 2014 European elections does not have empirical support in our analysis. Despite its short relationship with the EU, the BE seems to have given more importance to maintaining its traditional line of moderate enthusiasm about the EU rather than capitalising on the current lack of popularity for the Europe project among Portuguese voters.

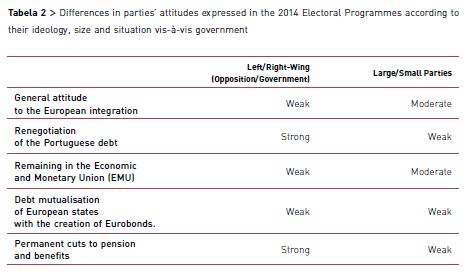

We now turn to our analysis of the differences between the positions expressed by the political parties in terms of their size, ideology and situation vis-à-vis government (government vs. opposition). Curiously, in 2014, the left/right-wing and opposition/government dichotomies overlap as both the right-wing parties are in government while the left-wing parties are in opposition. Table 2 shows that these factors have a weak to moderate impact on their positions on European integration, debt mutualisation through the creation of Eurobonds, and remaining in the EMU; there is no clear division between the two sides of each cleavage analysed. In these three questions, the two largest parties tend to take the same position, while the two smaller parties diverge, largely due to the differentiated statements and choices of the BE. The range of positions found among the main left-wing parties in opposition does not allow us to state there are striking differences in party positioning on these three subjects due to ideology or the parties’ situation vis-à-vis government. Quite the contrary, the opinions on renegotiating the Portuguese debt and the cut in pensions are marked by a strong left vs. right-wing divide, or a government vs. opposition divide, in which the left-wing/opposition parties are clearly more in favour of renegotiation and more against the cuts than the right-wing parties. The size of the parties has little impact; whereas the smaller parties express similar positions, the two larger parties express diverging attitudes in their official documents.

Conclusions

Ever since the «Europe with us» (‘A Europa connosco’) slogan, launched by the PS in the 1970s, public opinion and, above all, the political and economic elites in Portugal have had a positive perception of the European integration process. For many years, Europe was associated with prosperity, modernity and social progress. However, these well established facts have been questioned in recent years. Since the economic and financial crisis of 2008, and in particular the troika’s entry in Portugal in May 2011, this perception of European politics and its goodwill, and the purely positive vision of the EU has gone into decline. The 2014 European elections are taking place in this context and, as the first elections since the onset of the crisis, they are of great importance.

In this article, we have analysed five competition dimensions in the May 2014 European elections. The fundamental conclusion is that, despite the recent deterioration in the public’s opinion of the EU, there is remarkable continuity in the positions on the Europe project held by the parties with parliamentary representation. For example, despite the cleavage on the renegotiation of the public debt, Portugal’s main political parties (PS and PSD, the latter in a coalition with the CDS-PP) still agree that Portugal should remain in the EU and the Economic and Monetary Union. The CDU, which is the most Eurosceptic in the Portuguese party system, maintains its usual position. As for the BE, even though it is one of Europe’s left-wing parties, in fact its position on Europe is somewhat ambiguous and half-hearted.

Taking into account the moment when this article was written (a few weeks before the European elections), and the focus on five specific dimensions rather than a more wide-ranging approach, this is a preliminary and partial analysis. Indeed, anything can still happen in terms of the political communication the parties’ positions on Europe and the economic crisis. Notwithstanding, in light of the constraints associated with the positions taken by the main players in the Portuguese party spectrum, it is extremely unlikely that major changes will take place in the panorama outlined herein. Whatever the case, our conclusions can only gain from subsequent validation and confirmation after the end of the 2014 European election campaign.

TRANSLATION BY: RACHEL EVANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BE - Manifesto «Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade», 2014 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.bloco.org/media/IIconf_recom_eur.pdf.

BLYTH, Mark - Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [ Links ]

CDU - Manifesto «Um Portugal com Futuro numa Europa dos Trabalhadores e dos Povos», 2014 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.pcp.pt/sites/default/files/documentos/declaracao_programatica_pcp_eleicoes_parlamento_europeu_2014.pdf.

DE VREESE, Claes H.; BANDUCCI, Susan; SEMETKO, Holly A.; BOOMGAARDEN, Hajo A. - «The news coverage of the 2004 European Parliamentary election campaign in 25 countries». In European Union Politics, Vol. 7, N.º 4, 2006, pp. 477-504. [ Links ]

DE VREESE, Claes H.; LAUF, Edmund; PETER, Jochen - «The media and European Parliament elections: Second-rate coverage of a second-order event?». In VANDERBRUG, Wouter; VANDEREIJK, Cees - European elections and domestic politics. Lessons from the past and scenarios for the future. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007, pp. 116-130. [ Links ]

DINAS, Elias; GEMENIS, Kostas – «Measuring parties’ ideological positions with manifesto data: a critical evaluation of the competing methods». In Party Politics. Vol.16, N.º 4, 2010, pp. 427-450.

«Entrevista de Marisa Matias», Expresso, 29th March 2014, p. 15.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION – Standard Eurobarometer 80 (Online). 2013 (accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb80/eb80_en.htm.

FREIRE, André – «As eleições europeias em Portugal». In Relações Internacionais. Vol. 6, 2005, pp. 119-125.

HOOGHE, Liesbet; MARKS, Gary; WILSON, Carole J. – «Does left/right structure party positions on European integration?». In Comparative Political Studies. Vol. 35, N.º 8, 2002, pp. 965-989.

JALALI, Carlos – «Governing from Lisbon or Governing from Brussels? Models and tendencies of europeanization of the Portuguese Government». In TEIXEIRA, Nuno Severiano; PINTO, António Costa – The Europeanization of Portuguese Democracy. Nova York: Columbia University Press, 2012, pp. 61-84.

JALALI, Carlos; SILVA, Tiago - «Everyone Ignores Europe? Party Campaigns and Media Coverage in the 2009 European Parliament Elections». In MAIER, Michaela; STROMBACK, Jesper; KAID, Linda. L. - Political Communication in European Parliamentary Elections. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2011, pp. 111-126. [ Links ]

LEWIS-BECK, Michael; PALDAM, Martin - «Economic voting: an introduction». In Electoral Studies. Vol. 19, N.º 2-3, 2000, pp. 112-121. [ Links ]

LEWIS-BECK, Michael; STEGMAIER, Mary – «Economic determinants of electoral outcomes». In Annual Review of Political Science. Vol. 3, 2000, pp. 183-219.

LOBO, Marina Costa - «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática». In LOBO, Marina Costa; LAINS, Pedro – Em Nome da Europa. Portugal em Mudança (1986-2006). Estoril: Principia, 2007, pp. 78-96.

LOBO, Marina Costa – «Portuguese attitudes towards the EU membership: Social and political perspetives». In South European Society and Politics. Vol. 8, N.º 1, 2003, pp. 97-118.

LOBO, Marina Costa - «Still second-order? European Parliament elections in Portugal». In PINTO, António Costa – Contemporary Portugal: Politics, Society and Culture. 2.ª ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011, pp. 249-273.

MAGALHÃES, Pedro C. - «Introduction: financial crisis, austerity, and electoral politics». In Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. Vol. 24, N.º 2, 2014, pp. 125-133. [ Links ]

PAPPAS, Takis S. - «Why Greece failed». In Journal of Democracy. Vol. 24, N.º 2, 2013, pp. 31-45. [ Links ]

PCP - Projeto de Resolução Política, 2012 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://pcp.pt/sites/default/files/documentos/teses_projeto_de_resolucao_politica.pdf.

PORTUGAL - Programa do XIX Governo Constitucional (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/130538/programa_gc19.pdf.

PS - Declaração de Princípios de outubro de 2010 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.ps.pt/images/stories/pdfs/declaracao_de_principios_2010.pdf.

PS - Declaração «Novo Rumo para Portugal». (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://novorumopa-raportugal.pt/Assets/documents/declaracao-novo-rumo-para-portugal.pdf.

PS - Moção «Portugal tem futuro» (Online). Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.ps.pt/images/imprensa/mocao_a_portugal_tem_futuro.pdf.

PS - Programa eleitoral das eleições legislativas, 2011 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://downloads.sol.pt/pdf/ps.pdf.

PSD - Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014 (Online). (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.psd.pt/ficheiros/dossiers_politicos/dossier1394024861.pdf.

«PSD/CDS apresenta programa eleitoral em jeito de tweets e “101 dálmatas”», Público (Online). 5th March, 2014 (Accessed on 1st April, 2014). Available at: http://www.publico.pt/politica/noticia/psdcds-apresenta-programa-eleitoral-em-jeito-dos-tweets-e-dos-101-dalmatas-1627124.

REIF, Karlheinz; SCHMITT, Hermann - «Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results». In European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 8, N.º 1, 1980, pp. 307-340. [ Links ]

RUIVO, João Pedro; MOREIRA, Diogo; COSTA PINTO, António; ALMEIDA, Pedro Tavares – «Portuguese political elites and the European Union». In TEIXEIRA, Nuno Severiano, PINTO, António Costa – The Europeanization of Portuguese Democracy. Nova York: Columbia University Press, 2012, pp. 27-59.

SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, representation and scope of governance in the euromanifestos (19872004)». In Perspetives on European Politics and Society. Vol. 11, N.º 2, 2010, pp. 183-200.

SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues - «Portugal». In Conti, Nicolò – Party Attitudes Towards the EU in the Member States: Parties for Europe, Parties Against Europe. Londres: Routledge, 2014, pp. 115-132.

SPOON, Jae-Jae - «How salient is Europe? An analysis of European election manifestos, 1979-2004». In European Union Politics. Vol. 13, N.º 4, 2012, pp. 58-579. [ Links ]

Date received: 24th March, 2014 | Date approved: 27th April, 2014

ENDNOTES

* This paper was first published in Relações Internacionais no.41, March 2014.

1 BLYTH, Mark - Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

2 MAGALHÃES, Pedro C. - «Introduction: financial crisis, austerity, and electoral politics». In Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. Vol. 24, N.º 2, 2014, pp. 125-133.

3 PAPPAS, Takis S. - «Why Greece failed». In Journal of Democracy. Vol. 24, N.º 2, 2013, pp. 31-45.

4 LOBO, Marina Costa - «Still second-order? European Parliament elections in Portugal», In PINTO, António Costa – Contemporary Portugal: Politics, Society and Culture. 2.ª ed. Nova York: Columbia University Press, 2011, pp. 249-273.

5 This and other data on the attitudes of Portuguese public opinion on Europe were taken from the Standard Eurobarometer 80 during the autumn of 2013. The survey’s main results are available in the Eurobarometer’s official website. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb/eb80/eb80_en.htm (accessed on 1st April, 2014).

6 LEWIS-BECK, Michael; PALDAM, Martin - «Economic voting: an introduction». In Electoral Studies. Vol. 19, N.º 2-3, 2000, pp. 112-121; LEWIS-BECK, Michael; STEGMAIER, Mary – «Economic determinants of electoral outcomes». In Annual Review of Political Science. Vol. 3, 2000, pp. 183-219.

7 REIF, Karlheinz; SCHMITT, Hermann - «Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results». In European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 8, N.º 1, 1980, pp. 307-340.

8 REIF, Karlheinz; SCHMITT, Hermann - «Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results», 307-340.

9 LOBO, Marina Costa - «Still second-order? European Parliament Elections in Portugal», pp. 249-273.

10 JALALI, Carlos; SILVA, Tiago - «Everyone Ignores Europe? Party Campaigns and Media Coverage in the 2009 European Parliament Elections». In MAIER, Michaela; STROMBACK, Jesper; KAID, Linda. L. - Political Communication in European Parliamentary Elections. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2011, pp. 111-126; DE VREESE, Claes H.; LAUF, Edmund; PETER, Jochen - «The media and European Parliament elections: Second-rate coverage of a second-order event?» In VANDERBRUG, Wouter; VANDEREIJK, Cees - European elections and domestic politics. Lessons from the past and scenarios for the future. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007, pp. 116-130; DE VREESE, Claes H.; BANDUCCI, Susan; SEMETKO, Holly A.; BOOMGAARDEN, Hajo A. - «The news coverage of the 2004 European Parliamentary election campaign in 25 countries». In European Union Politics, Vol. 7, N.º 4, 2006, pp. 477-504.

11 JALALI, Carlos; SILVA, Tiago - «Everyone ignores Europe? Party campaigns and media coverage in the 2009 European Parliament Elections», pp. 111-126.

12 SPOON, Jae-Jae - «How salient is Europe? An analysis of European election manifestos, 1979-2004». In European Union Politics. Vol. 13, N.º 4, 2012, pp. 58-579.

13 SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues - «Portugal». In Conti, Nicolò – Party Attitudes Towards the EU in the Member States: Parties for Europe, Parties Against Europe. London: Routledge, 2014, pp. 115-132.

14 LOBO, Marina Costa - «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática». In LOBO, Marina Costa; LAINS, Pedro – Em Nome da Europa. Portugal em Mudança (1986-2006). Estoril: Principia, 2007,

pp. 78-96.

15 SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues – «Portugal», pp. 115-132.

16 SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, representation and scope of governance in the euromanifestos (19872004)». In Perspetives on European Politics and Society. Vol. 11, N.º 2, 2010, pp. 183-200.

17 HOOGHE, Liesbet; MARKS, Gary; WILSON, Carole J. – «Does left/right structure party positions on European integration?». In Comparative Political Studies. Vol. 35, N.º 8, 2002, pp. 965-989.

18 SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, Representation and Scope of Governance in the Euromanifestos (1987--2004)», pp. 183-200.

19 JALALI, Carlos – «Governing from Lisbon or Governing from Brussels? Models and tendencies of europeanization of the Portuguese Government». In TEIXEIRA, Nuno Severiano; PINTO, António Costa – The Europeanization of Portuguese Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012, pp. 61-84; RUIVO, João Pedro; MOREIRA, Diogo; COSTA PINTO, António; ALMEIDA, Pedro Tavares – «Portuguese political elites and the European Union». In TEIXEIRA, Nuno Severiano, PINTO, António Costa – The Europeanization of Portuguese Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012, pp. 27-59.

20 JALALI, Carlos – «Governing from Lisbon or governing from Brussels? Models and tendencies of europeanization of the Portuguese Government», pp. 61-84.

21 SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, representation and scope of Governance in the euromanifestos (1987-2004)», pp. 183-200.

22 LOBO, Marina Costa – «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática», p. 83.

23 DINAS, Elias; GEMENIS, Kostas – «Measuring parties’ ideological positions with manifesto data: a critical evaluation of the competing methods». In Party Politics. Vol.16, N.º 4, 2010, pp. 427-450.

24 LOBO, Marina Costa – «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática», pp. 78-96; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, representation and scope of governance in the euromanifestos (1987-2004)», pp. 183-200; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues – «Portugal», pp. 115-132.

25 It is important to note that, for analytical purposes, we have considered Portugal Alliance (PSD and CDS-PP) as a single actor. Although their positions on European matters have followed different trajectories (see the works by Marina Costa Lobo and José Santana-Pereira and Edalina Sanches, quoted throughout the article), and were even quite distinct on core governance matters during the Passos Coelho government, we are sure both parties were basically in agreement on the five dimensions analysed in the spring of 2014.

26 SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues – «Portugal», pp. 115--132.

27 We would like to thank our colleagues Ana Espírito Santo, Tiago Silva and Carlos Nogueira for their valuable help in identifying and collecting these documents.

28 Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014. Available at: http://www.psd.pt/ficheiros/dossiers_politicos/dossier1394024861.pdf (accessed on 1st April, 2014).

29 «PSD/CDS apresenta programa eleitoral em jeito de tweets e “101 dálmatas”», in Público, 5th March, 2014. Available at: http://www.publico.pt/politica/noticia/psdcds-apresenta-programa-eleitoral-em-jeito-dos-tweets-e-dos-101-dalmatas-1627124 (accessed on 1st April, 2014).

30 Programa do XIX Governo Constitucional. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/130538/programa_gc19.pdf.

31 The Socialist Party was the only party that had still not made their election programme for the 2014 European elections available at the time of writing (end of March 2014).

32 PS, Declaração de Princípios de outubro de 2010. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.ps.pt/images/stories/pdfs/declaracao_de_principios_2010.pdf (accessed on 1st April 2014).

33 PS, Programa eleitoral das eleições legislativas, 2011 (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at http://downloads.sol.pt/pdf/ps.pdf.

34 PS, Moção «Portugal tem futuro». (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.ps.pt/images/imprensa/mocao_a_portugal_tem_futuro.pdf.

35 PS, Declaração «Novo Rumo para Portugal». (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://novorumopa-raportugal.pt/Assets/documents/declaracao-novo-rumo-para-portugal.pdf.

36 CDU, Manifesto «Um Portugal com Futuro numa Europa dos Trabalhadores e dos Povos», 2014. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.pcp.pt/sites/default/files/documentos/declaracao_programatica_pcp_eleicoes_parlament_europeu_2014.pdf.

37 BE, Manifesto «Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade», 2014. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http:// www.bloco.org/media/IIconf_recom_eur.pdf.

38 LOBO, Marina Costa – «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática», pp. 78-96; FREIRE, André – «As eleições europeias em Portugal». In Relações Internacionais. Vol. 6, 2005, pp. 119-125; LOBO, Marina Costa – «Portuguese attitudes towards the EU membership: Social and political perspetives». In South European Society and Politics. Vol. 8, N.º 1, 2003, pp. 97-118.

39 Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014, p. 2.

40 PS, Declaração de Princípios de 2010, pp. 17-18.

41 CDU, Manifesto «Um Portugal com Futuro numa Europa dos Trabalhadores e dos Povos», 2014, p.5.

42 Ibidem, p. 14.

43 BE, Manifesto «Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade», 2014, p. 6.

44 Ibidem.

45 Due to the lack of an official document on the coalition's common position on this matter, we used the electoral programme of PSD and CDS-PP, respectively on this specific point. Cf. Programa Eleitoral PSD 2011, p. 33.

46 Cf. Programa Eleitoral CDS-PP 2011, no page.

47 Programa Eleitoral PS, 2011, p. 13.

48 Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014, p. 3.

49 Ibidem.

50 Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014, p. 12.

51 BE, Manifesto «Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade», 2014, p. 1.

52 Interview with Marisa Matias, Expresso, 29th March 2014, p. 15.

53 CDU, Manifesto «Um Portugal com Futuro numa Europa dos Trabalhadores e dos Povos», 2014, p.5.

54 Manifesto Aliança Portugal – Europeias 2014, p. 7.

55 Position available on the party's official site. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.ps.pt/posicoes-do-ps/europa/eurobonds.html.

56 BE, Manifesto «Desobedecer à Europa da Austeridade», 2014, p. 8.

57 Projeto de Resolução Política, 2012. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://pcp.pt/sites/default files/documentos/teses_projeto_de_resolucao_politica.pdf.

58 Programa do XIX Governo Constitucional, p. 86. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/130538/programa_ gc19.pdf.

59 Programa do XIX Governo Constitucional, p. 85. (Consulted on: 1st April 2014). Available at: http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/130538/programa_ gc19.pdf.

60 LOBO, Marina Costa – «A União Europeia e os partidos políticos portugueses: da consolidação à qualidade democrática», pp. 78-96; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José – «Which Europe do the Portuguese political parties want? Identity, representation and scope of governance in the euromanifestos (1987-2004)», pp. 183-200; SANTANA-PEREIRA, José; SANCHES, Edalina Rodrigues – «Portugal», pp. 115-132.