Introduction

We live in exceptional times that require new ways of understanding and managing a world with different configurations and unpredictable trends. It also requires the ability to simultaneously react to new global challenges and risks. Among them, security stands out: security of individuals, societies, and other living species.2 As the editor of The Economist Tom Standage wrote last 14 November,

‘the pandemic marked the end of a period of relative stability and predictability in geopolitics and economics. Today’s world is much more unstable, convulsed by the vicissitudes of great-power rivalry, the aftershocks of the pandemic, economic upheaval, extreme weather, and rapid social and technological change. Unpredictability is the new normal’3.

The COVID-19 has also reshaped human mobility worldwide through the imposition of lockdowns, and reinforced the vulnerability of some specific and already vulnerable individuals. Such as migrants, no matter where or what age or sex. Given the peculiarities of their own circumstances, they became in most regions of the world even more vulnerable than they were before the onset of the sanitary crisis. In host societies, the vast majority faced increased vulnerabilities if compared to the rest of the population, due to their institutional framework, lack of or unclear formal rights and information, constraints to access health care and social security systems, isolation, lack of or limited sources of income. And also to the difficulty in maintaining their jobs in a time of economic uncertainty, despite the fact that it has often been pointed out the importance of migrant workers in some basic sectors of society.4 Furthermore, the pandemic also affected long-term migrants due to the expected economic breakdown, with many countries facing an economic crisis with no predictable end.

Our purpose is to offer insights on migrants’ vulnerability in the context of the sanitary crisis. In a diverse Europe running at different speeds, the pandemic outbreaks and the exceptionality required for its management has exposed persistent social and economic idiosyncrasies that intensified the already existing contexts of vulnerability for migrants, even though the specific consequences vary. With the effects of the pandemic as our framework, we include a brief introduction on the multiple reasons that justify the global migration process, and discuss the conceptual basis that links migrants’ vulnerability with the concept of human security. We also add some examples of measures taken by European countries to face the pandemic effects during the initial years and the way they covered migrant populations, namely through the implementation of exceptional legislation due to the recognition of their specific circumstances in host societies.

A world on the move. Multiple reasons to get going

The COVID-19 accelerated some trends of change that were on the horizon in the international system and, swept by it and in its wake, we moved from the VUCA to the BANI world.5 This BANI world coexists with a paradigm shift centered on individual human beings and based on holistic and cooperative ways of seeing and acting. The new features enhance the migratory phenomenon because they produce and accentuate the distance between expectations and real living conditions, facilitated by access to profuse information and fast mobility options. Will, necessity and ease are three pillars of contemporary migrations, but only 3.6% (a total of 281 million) of them are international migrants.6

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the characteristics of migration changed considerably. They became different in their causes, and more sensitive and reactive to political and socioeconomic conjuncture change, in prevailing profiles (due to the feminization of migration), arrangements (all countries have emigrants, immigrants and various types of migrants - workers, refugees, asylum seekers), origins and destinations (with the increase of south-south migrations), and also the politicization of which they are targeted.

All countries are today simultaneously receivers and emitters of migrants, regardless of their economic and human development rate, and the variety of migratory causes has increased, although economic motivations continue to prevail. Migration dynamics elude predictability logics, given the interference of a set of multiple exogenous factors, which condition and determine volumes, trends and migratory routes: from the tangible effects of climate change to the succession of geopolitical events, the understandings and political agreements between states and international organizations, the social and identity perceptions of the citizens of host societies, challenges of the labor market profiles and their balances.7

Along with the growing complexity of the migration causes, the volume of forced migration also grew. At the end of 2021, 89.4 million people lived away from their birthplace, about 39% due to new and old conflicts and the remaining 61% due to natural disasters (floods, droughts, storms). The impact of these human displacements affects both host and transit regions, where many remain for long periods.8 More than 80% of forced migration occurs in countries with low human development indicators and acts as a likely element of social tension and political instability. These are the places from which an overwhelming majority of irregular migrants depart, most of them in particularly vulnerable situations. Chapter 6 of the World Migration Report 2022, entitled ‘Peace and security as drivers of stability, development and safe migration’9 speaks of a ‘birth lottery’ that punishes those who, having been born in poor regions, are this reason the main victims of the difficult migration process, which, even when voluntary, tends to be done in less safe conditions. The Sustainable Development Goal 16 also focuses on this topic, and highlights the duty of the states to ensure their citizens the right to peace, justice and strong institutions.

One in every seven individuals is a migrant, whether with the status of unqualified worker, refugee, student, highly qualified professional or other, and every minute 24 individuals leave their usual residence. We are talking mainly of short-distance movements, but in the context of rapid changes (induced by climate change and the relative globalization of conflicts) the areas of destination of those internally displaced persons (IDPs) will probably amplify. By generating forced collective migration processes, environmental changes act as multipliers of risks and threats and as potential catalysts of tensions and conflicts related to food insecurity processes, struggle for access to clean water, energy and other vital resources. A total of 59.1 million are today IDPs, 26.4 million are refugees and 4.1 million asylum seekers.10 The coming decades will be affected by the unavoidable increase of environmental migration, internal and international in the south-south context.11

A united Europe?

With 748.8 million residents,12 Europe needs migrants. The old continent faces a peculiar situation in the context of demographic dynamics, which might generate several constraints in the medium term. These are related with the undergoing and consistent demographic ageing phenomenon, the insufficient fertility levels to ensure the replacement of generations, the increasing dependency on migration balance to assure population volumes. In more than 67% of European countries, the annual total of deaths exceeds or is about to surpass that of births, and dependence on migration continues to rise. Migration can mitigate the unwanted effects (namely economic) of this ‘demographic winter’, as the European destiny continues to be the one most coveted at a global scale. So, we may assume that the future of European societies relies on their capacity to manage the consequences of ageing phenomenon and migration flows, particularly in the sectors of economic activity, the labor market and the social protection systems.

The same need for working age population occurs in the European Union (EU), although with significant differences between member states (MSs) associated to unequal migratory attractiveness capacity.13 After the decline in population growth in 2020 due to COVID-19, the EU’s population decreased again in 2021.14 The present EU’s inability to hold on to its residents (446.8 million in 2022) is perceived as a weakness, with geopolitical and economic negative costs. According to demographic projections, the EU population might recover within a few years if migration balances rise, but the average age of the residents will also rise, the relative weight of population below 64 years old will drop, and a decline on GDP is expected (from 1.25 to 2.25% per year) as a direct consequence of the ageing phenomenon.15

The profiles of migrant communities based on different MSs reflect the different national histories (former empires, privileged political or diplomatic relations, common official language). In total, the EU has 39 million legal migrants (2021), 23.7 million from third countries and 15 million from non-EU European countries. These numbers are annually increased by 1.5-2 million new arrivals. Altogether, migrants living in the EU represent 8.4% of the resident population, refugees 0.6% (but rising). The number of asylum seekers doubled between 2014 and 2015 and, in 2021, it stood at 630,500 (an increase of 33% compared to 2020, but a reduction of 10% compared to 2019). Irregular entries in 2020 were the lowest of the previous seven years (125,000) but increased by 60% in 2021 (c. 200,000). Around 199,000 individuals remain undocumented.16

Through migration, ‘old Europe’ guarantees demographic stability, increased productivity and liquid contributions.17 But migration flows also create mistrust in European countries, related to possible threats to sovereignty, national identity, international terrorism, and human trafficking. The connection between migration and security has become, in the last decades, a priority issue on the international political agenda, since it entails the management of an existing complex and growing phenomenon of uncertain evolution. The feeling of insecurity post 11 September created the conditions for the development of securitization theories. Seizing migration as a security problem results from the construction of a new set of threats, in which migrant flows are seen as a potential threat to the freedom and sovereignty of host societies. However, caution is advisable in what concerns speeches and practices, as we are experiencing an era of uncertainty and re-evaluation as to the future evolution of migration and the risks associated. The consequences will be vast and at various levels. Cooperation between the host and origin countries is essential to create common responses, efficient mechanisms, and inclusive and comprehensive migration policies that promote the integration of immigrants, but without relinquishing the defences against potential individual agemts of disturbance.

This explains why the EU27 continues to have an ambiguous relationship with regard to the management of migration flows. And why it continues to privilege the consolidation of a common policy, structured in the control of migratory flows, the fight against illegal immigration, the bet on integration policies, and the development of cooperation policies to assure standard procedures. The response to the recent humanitarian crises in the Mediterranean and Ukraine, and the significant increase of the number of regular migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, tested the validity of the existing practices to deal with unprecedented volume of entry requests, without denying the values that frame EU common policies. A huge number of initiatives has been taken since then, but they rely mostly in reactive responses to the increasing complexity of migration management.18 Millions of migrants from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East remain today in the EU territory, many of them in an illegal situation, either because they crossed the borders in violation of the law (clandestinely or with falsified documents) or as they remained in the EU without legal ground.19 Due to this status, in most circumstances they do not have the same rights and guarantees as regular migrants.20

For European countries to maximize positive aspects and mitigate the challenges facing international migrants, it is essential to preserve sustainable migration policies based on the principles of multidimensional integration. They must be grounded on the values of state sovereignty, the sharing of responsibilities, political dialogue between states, non-discrimination and respect for human rights. The Global Compact for Migration represents the best example of the humane approach, centered on the analysis of the different levels of vulnerability, and the goal of guaranteeing the conditions for a safe migratory project preserving individual and collective human rights. At the heart of this human security-based approach to migration, governance is the recognition of migrants’ vulnerability, which can be mitigated by a regime based on an international human rights law sensible to different categories of migrants.21 But, as we know, the Pact has divided opinions and exposed the dissent within the EU on migration issues. About a quarter of MSs refused to subscribe to the document.22 These very different understandings of the States were only partly altered by the pandemic.

Despite current legislation and the availability of human and technological means to ensure compliance and to monitor the good implementation of a complex yet solid migration and asylum policy, political officials face a difficult moment. Pressure at the EU’s external borders and fears regarding border management incapacity remain on the agenda, particularly from the domestic point of view. Is it possible that tolerance limits have been reached in European societies? The rise of anti-immigration feelings and the spread of populism and right-wing parties across Europe are grounded in ideas and speeches that equate major migratory flows with ‘invasion’ and loss of quality of life or national identity. Geography matters when it comes to perception about daily (visible) issues of migratory impact, and that explains why migration ranks for societies of both sides of the Atlantic is an important security challenge, according to the ‘2022 Transatlantic Trends’23.

The life of European migrants in exceptional pandemic times

This is the Europe that the pandemic will find. A Europe that remains divided regarding too many essential issues. Migration management is undoubtedly one of them, testified by individuals from all over the world who seek access to it, either legal migrants (mainly economic ones), refugees or asylum seekers.

In fewer areas is political commitment and collaborative exchange as crucial as in global health security. During the initial stages of the sanitary fight, the outbreak allowed in fact a greater alignment, on a global scale, with a view to finding solutions including scientific knowledge exchanges, Research and Development, and even economic mitigation solutions. But it did not nullify the mistrust among states or regions, or their specific idiosyncrasies and agendas. That is why the health crisis affecting Europe in 2020 has generated a huge perception of individual and collective insecurity. It accelerated previously existing trends and triggered new dynamics that might redefine global geopolitics. It also legitimized the (re)creation of robust political boundaries. Human flows were identified as the propagating agents of the disease, facilitated by the speed and intensity of transport and exchanges in the global village, and initial efforts were unanimous as to the need to ban mobility. However, the securitization of migration as responsible for the spread of the disease never happened. On the contrary, even in the most reluctant MSs concerning migration advantages, the prevalence of a humane security approach seemed to overcome, in compliance with human rights standards that inform the EU matrix. In fact, Europe and the EU were not the worst places in which to be a migrant during the pandemic.

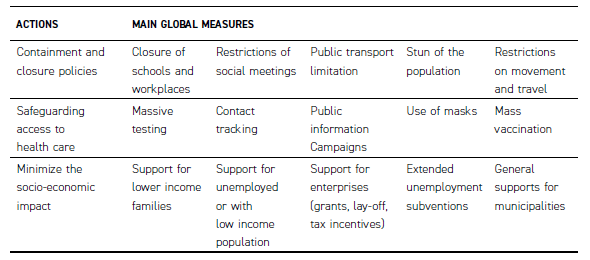

A wide range of emergency measures were implemented despite their temporary nature. The problem was that, once again, European countries often failed to address migrants’ specific vulnerabilities and material needs. The exception measures applied to all residents are synthesized in table 1 and identify three major goals: containment and closure policies, safeguarding access to health care, concern to minimize the negative socio-economic impact of the health crisis. These measures had also positive impacts for migrants, mostly for those with regular conditions of permanence. For the others, the applicability of some of them was difficult and with different practical effects.

Table 1 > General areas of intervention in EU countries to face COVID-19

Source: Own elaboration, based on Susana Ferreira.24

‘One size fits all’ is not always the best solution. The pandemic has stressed the risks to which migrants were exposed since the beginning of the crisis, and as the months went by, their vulnerability to its direct and indirect effects became clear.25 As European governments began setting lockdowns to ‘flatten the curve’ of the virus, migrants’ vulnerabilities were exacerbated. Although they are entitled to the same human and health rights as any other individual within the host society, they bump into obstacles to attain such rights (especially the irregular migrants, fearful of resorting to healthcare and being reported to the national immigration authorities). Language and cultural barriers are also daily problems, as well as access to work and working conditions. According to the Migration Data Portal, migrant workers were highly affected, even if their workforce was vital to assure the functioning of critical sectors that remained operative throughout the pandemic, such as agriculture, logistics, personal care and health-care provision, cleaning services and others.

The announcement of exceptional measures adjusted to migrant populations was undertaken in some EU countries, but it did not fully address their ‘situational’ vulnerability within host countries. Those procedures covered four main dimensions (figure 1): to regularize migrants with pending requests and other legal procedures, to guarantee their access to national healthcare systems when needed, to guarantee the possibility of benefiting from essential welfare services similar to all national residents, as well as the right to work conditions surveillance and access, no matter their legal status in host countries or wherever COVID-19 happened to trap them.

Figure 1 > The social inclusion of migrants. Adoption of exceptional measures & centrality of human rights. Source: Own elaboration, based on Susana Ferreira and Teresa Rodrigues.26

The general closure of the national migration services, even when substituted by telework conditions, stopped the normal procedures towards migrants’ document regularization/legalization (namely concession or renewal of residence permits). A practical measure in line with human security agenda, and one of the most common decisions between MSs comprised the adoption of exceptional instruments to solve the legal situation of migrants with requests that were pending when the pandemic began (Portugal was a pioneer in this field). This policy measure simultaneously tackled a bureaucratic problem created by the state of emergency, and ensured migrants’ human rights, granting them the same rights as all other citizens to help them get through those exceptional times. Depending on national decision, those documents worked as temporary authorisations and were considered valid for access to essential or to all public services (obtaining a health user number and access to the National Health Service and other healthcare rights, access to social support benefits, signing house rental agreements and employment contracts, opening bank accounts and contracting other public services). However, there were gaps between political decisions and practice. The strategy of temporarily considering expired documents as valid for an extended period raised numerous practical obstacles in migrants’ daily life (the conclusion of employment contracts, leases, effective access to healthcare services).

The prevalence of precarious jobs among migrant communities explains why they were the first ones to feel the impact of the pandemic. They were one of the populations most affected by unemployment, predominantly the informal economy workers, exposed to the lack of protection in situations of unemployment, and also the most vulnerable to bankruptcies due to confinement measures. The consequences of job loss had obvious negative consequences, such as how to ensure housing and food. In some countries, the loss of contractual employment ties also meant the loss of formal conditions to remain in the host country. Not all MSs seem to identify this aspect as a core issue, but indeed it constituted a vulnerability and had considerable repercussions on migrants’ socio-economic dimensions.

COVID-19 has made a clear case for the need to adopt EU27 common effective integration policies guided by a human-rights approach. Migrants’ social inclusion is a pivotal axis in migration governance, since migrants are at a disadvantage vis-à-vis destination societies, particularly in the early stages of the migration process. The lack of knowledge of the language, culture, social and political organization, the educational system and the way in which society works in general hinder the process of integration of these citizens, which became more strained due to the pandemic. As a response to migrants’ vulnerability during the pandemic, the centrality of human rights is paramount to safeguard migrants’ needs and particular circumstances.

Final remarks

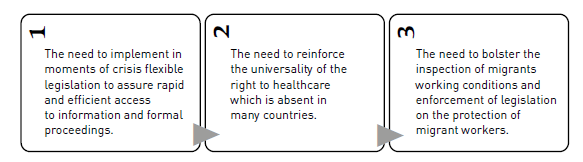

When COVID-19 reached the EU, the political and social responses were different at a preventive and prophylactic level, according to MSs political, economic and social specificities. An outline of those differences has been already provided.27 The pandemic had a particularly negative effect on migrants, exacerbating the already existing cleavages and integration problems. There is still a long way to go to reduce the differences between migrants and European host populations.28 The pandemic crisis has exposed the already existing discrepancies in various ways: directly in the solutions offered to guarantee the legal right to remain in the country and to be recognized the permission to access health care systems; indirectly in safeguarding access to welfare services (such as housing, adequate isolation conditions, if necessary, food supply), and to guarantee subsistence (through work offer and/or reliable working conditions, temporary benefits). The degree of success of those initiatives varied, and helps us to identify the most relevant lessons learned in the management of migrants during the pandemic crisis, which can be replicated in future crisis conjunctures, whether they will be caused by a health crisis or by something else (figure 2).

Figure 2 > Migration management in a time of crisis. Lessons learned. Source: Own elaboration, based on Susana Ferreira and Teresa Rodrigues.29

EU countries differed in their willingness and capacity to cope with these general lines of action, and most of them opted to assume a standard approach in the fight against the disease, without implementing comprehensive measures requiring adjustments to different profiles or minority communities living under their flag. The common solutions had mostly practical goals and three main areas of intervention. The first highlights the need, in times of emergency, for the necessary legislative flexibility to implement exceptional measures that may assure rapid and efficient access to information and to formal proceedings, and guarantee to all migrants, regardless of their legal condition, the full maintenance of its rights (such as the possibility to remain in the country even if their legal status is not yet defined, and to be granted basic human rights besides health, housing, food, education and employment).

The second reinforces the right to equal access to healthcare regardless of status or birthplace. Protecting the right to health becomes even more important for vulnerable groups, often threatened by social exclusion, as they tend to present lower health levels due to their own socioeconomic circumstances (deficient living and working conditions, unfamiliarity with the health system, language barriers and cultural differences). In international human rights law, this right does not allow discrimination based on the migratory status, but there is an omission regarding irregular migrants, which turns into a symbolic discrimination in national laws. Thus, providing free access to irregular migrants to the healthcare system and ensuring that they remain undetected by immigration authorities is imperative to ensure their human right to health care, enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (art. 35th).

The third identifies as urgent the need to bolster the inspection of migrants’ working conditions and the enforcement of legislation on migrant workers’ protection. Examples of employers’ abuse and economic illicit traffic are constant and made public by the media. A robust inspection on working conditions in some economic sectors would avoid the risk that less informed migrants might fall into the traps of illegal work.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected migrant people at the confluence of a health crisis, a socio-economic crisis and a protection crisis. To assure a strong, sustained and truly inclusive post-pandemic recovery, European countries must invest in more effective integration policies, and assume a dynamic approach with the developing countries from which most migrants come from. This is an opportunity to strengthen the sharing of responsibilities and international migration governance under the goals of the 2030 Agenda. A human rights-based approach to migration ensures the human security of migrants and produces more lasting and sustainable outcomes.

Thus, the crisis has generated the momentum EU was lacking to consolidate a new migration paradigm that places human rights at the core of migration and integration policies. But there is still a long road ahead. As far as the EU is concerned, the different approaches to migration and migrant integration policies will continue to be tested in a volatile reality, in which different views persist on the advantages and disadvantages of migrants who will continue to arrive in Europe, who needs this young population to mitigate the unwanted effects of its own demographic winter.