We are living turbulent times, not unlike those that marked the early years of the 20th century when the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic caused forty million deaths within three months.2 This global health crisis was compounded by the deadly effects of the First World War and both calamities led to a major series of protests in subsequent years. From the second half of the 20th century through to the present day, there have been other times of serious social unrest, among them those of 1968 with the workers’ and students’ revolts, the Arab Spring of 2011, the Occupy movement, and the indignados movement. The past decade has been notorious for high levels of contestation worldwide, largely triggered by the 2008 financial crisis and the effects of austerity policies.3

This is the context in which the 2020 global health crisis erupted as a result of the COVID-19 virus, a variant of the SARS-CoV virus (2003), giving rise to new protests and intensifying those that had marked the previous years. The emergence of the new pathogen was recorded in November 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan and, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, the virus had already infected more than 96 million people and caused two million deaths by January 2020. The speed at which COVID-19 spread worldwide posed a major challenge for the institutions, first in managing the resulting health crisis and, afterwards, the ensuing social and economic effects. Although pandemics are not a rare phenomenon in modern history - with at least eight documented in the last century - tackling them effectively remains a difficult task for governments.4

The problems unleashed by the pandemic were manifested in several domains: millions of deaths and deteriorating health for many people, a serious economic recession, a deepening of existing divides (economic, gender, digital, generational, etcetera), growing distrust of institutions, and major mental health problems in the population as a whole due to ongoing individual isolation and lack of social interaction. Not only were institutions struggling to manage the crisis and the various dimensions of its effects, they were also having to deal with the politicisation of misinformation about the pandemic.

All these elements came together to create a breeding ground, especially in cities, for a range of expressions of social unrest which are still only vaguely understood despite preliminary efforts being made in academia to remedy this.5 In the scope of this study, I shall endeavour to provide some keys for interpreting this phenomenon, with particular attention to the links between the pandemic, protests, and social unrest in urban settings.

According to a report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), ‘pandemics lead to social unrest by lowering growth and raising inequality’.6 Accordingly, the IMF argues that there is a clear link between pandemic, inequality, and serious social tensions. In this study, I shall attempt to contribute some empirical elements related with this issue, basically in response to two questions. First, how is inequality related with growing social unrest in situations of health crisis such as the one which was caused by COVID-19? In other words, have there been more protests in countries with greater (pre- and post-pandemic) inequalities? Second, how do these phenomena (impact of the pandemic, inequalities, and protests) materialise in cities?

To address these questions, I shall first analyse the main trends, in terms of social protests, which have occurred on a worldwide scale over the last decade, after which I shall focus my inquiry on what has happened within the Atlantic region during the COVID-19 era. I shall proceed to demonstrate how the countries registering the highest levels of social unrest have been the United States, France, and Mexico. I shall then examine, from a historical perspective, how pandemics have affected cities and, in the Atlantic region, which cities have seen the greatest numbers of protests in the COVID-19 era. Finally, in seeking to establish the links between pandemic, inequalities, and cities, I conclude that urban social protests do not take place in the short term in geographical settings with more inequality problems. However, as the International Monetary Fund forecasts, they are likely to proliferate in the medium term (14 to 24 months after the crisis) in low- or lower-middle-income countries.

Methodology and scope of the study

In carrying out this study, I have opted to apply protest event analysis (PEA), one of the most commonly used research methods in the study of social movements over the last few decades. While protest studies initially used mainly qualitative research methods, the use of quantitative techniques has increased in the last decade thanks to the greater possibilities offered by certain technological tools for collecting and systematising data. PEA, a variant of the research tool of content analysis, enables systematic evaluation of the number and characteristics of protests occurring in different geographical areas (from local to supranational domains), while also making it possible to establish comparative readings across territories, time periods, and themes.

The source of information concerning social tensions that is used in this study is the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) Project, a database that collects disaggregated data, maps, and analyses social conflicts around the world. Among scholars in the field, it is considered that ‘ACLED [is] the most reliable and complete source of data on conflicts and disorder patterns worldwide’.7 In the Atlantic region, ACLED’s territorial coverage extends to Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe, and the United States. Its chief sources of information are: i) the media (sub-national, regional, national, and international); ii) reports (of international organisations, NGOs, and government institutions); iii) local partners; and iv) social networks (selected and verified).8

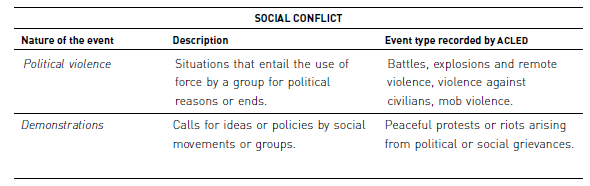

ACLED scrutinises five types of events which it considers to be indicators of situations of social unrest: i) battles; ii) violence against civilians; iii) explosions and remote violence; iv) riots; and v) protests.9 The following table shows the events that are predefined by ACLED and systematises them in keeping with their nature. These five kinds of events can be synthesised under two headings of social unrest or, in other words, whether they involve political violence or, on the contrary, are deemed to be social manifestations (table 1).

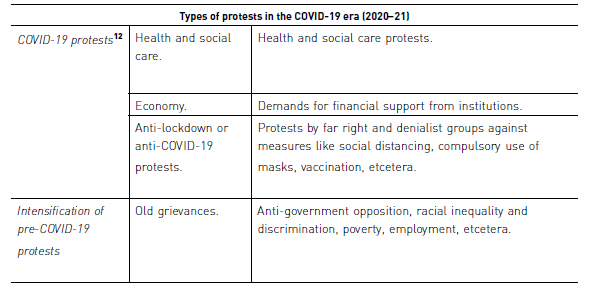

This study takes the second category as its unit of analysis, using the terms protests, mobilisations, and demonstrations as interchangeable references. The time frame covered is 2020 and January to June 2021. As this paper shows throughout, the pandemic has given rise to various kinds of manifestations within this period, which can be conceptualised as follows in table 2.

It should be noted that, along with these expressions of social unrest, the pandemic has also prompted multiple expressions (and actions) of support and social solidarity through, for example, applauding health workers (from balconies, by means of flash mobs) and experiences of joint activities which, from neighbourhoods and communities, have managed to offer help and support to more vulnerable groups.10 It is beyond the scope of the present study to enter into the analysis of these instances of solidarity, but it is important to draw attention to their existence so as not to give the erroneous impression that the pandemic has mostly sparked protests and social unrest.

Needless to say, the research method I have chosen for this study is not without its limits. It is important to be aware that the situations recorded by ACLED, while quite exhaustive, do not cover the totality of protests that have occurred in the COVID-19 era.

Like any exercise in identifying and mapping protests, this is a selective sample. Hutter warns of several factors which, generally speaking, explain the existing limitations in the sources of information used when recording protests, amongst which I would emphasise two: i) the characteristics of the events (including the larger and more violent ones which have greater media coverage, those that prompt counter-protests, those with a police presence, and those that have the support of some or other organisation), and ii) the characteristics of the issues that give rise to the protests (when those that refer to more generalised concerns have more media coverage).12 This study cannot avoid the biases in ACLED’s selection of information. It should also be noted that protests that might have occurred in the digital media and which, on account of this, are not recorded by ACLED, are beyond the scope of this study.

On the concept of social unrest

As Renn, Jovanovic, and Schröter point out, social unrest is comprised by complex situations that can be caused by social phenomena, accidents, and natural disasters.13 It usually happens when people are extremely unhappy about the situation they are in, feeling that it is unfair, or the result of unequal conditions, or fearing for their health, living conditions, and livelihoods. In these cases, collective anger or outrage can take the form of mobilisations, demonstrations, protests, riots, and even political violence.

These are phenomena connected with immediate reality, since they can have major consequences in several domains: social (rise of conflicts), political (fall of a government), and legal (recognition of a right or adoption of certain legal measures). Similarly, social unrest is not detached from history either, as protests are frequently the culmination of historical incidents or situations which, having generated social tensions, are later manifested as demands by citizens.

Renn Jovanovic, and Schröter warn that the academic literature does little by way of analysing social unrest per se.14 The scientific texts are more often concerned with measuring social unrest by means of indicators that with delineating it from the theoretical standpoint. Hence, the approaches are more empirical than conceptual. From a theoretical standpoint, it is necessary to turn to two different fields of study in order to approach some of the key aspects of social unrest,15 namely reflections on: i) political participation; and ii) social movements. In fact, these two bodies of academic literature do not constitute watertight domains of research but, in fact, show certain kinds of interaction between them and even some degree of overlapping.16

Political participation refers to actions by means of which citizens seek to influence decision-making in different spheres of the political system. Since the seminal work of Barnes and Kaase, this area of study has considerably evolved in keeping with new forms of political organisation, the kinds of actions involved, and the goals being pursued.17 Nevertheless, their theoretical contributions still prevail in academic interpretation of this phenomenon. Barnes and Kaase established a distinction between conventional and non-conventional forms of participation. The former mainly refers to the use of channels established by the voting system and electoral processes (in other words, they are conveyed through the socio-political conventions and agreements that structure democratic systems), while the latter term is a catchall for all the mass-based manifestations outside the bounds of legality and the institutional framework in force, for example, blocking streets or the various kinds of occupation18.

From the 1960s to the present day, the array of agents and channels of citizen expression has become more complex and diverse, which means that the distinction between conventional and non-conventional participation no longer captures the richness of the socio-political reality. Hence, some authors like Kaim suggest new categories like ‘alternative participation’, thus breaking with the dichotomy established by Barnes and Kaase and including all the forms of participation that did not come under either heading.19 Indeed, the advent of social movements represented a break with the classical forms of political organisation which, for most of the 20th century, were dominated by trade unions, political parties, and neighbourhood associations. The later emergence of the feminist, ecologist, civil rights, and the LGBTIQ+ rights movements would also bring into being repertoires of action based on the shaping of more fluid, informal networks through which the political participation of these groups has been channelled.20

Moreover, with the new millennium and the consolidation of the process of globalisation, the alter-globalisation movement took shape. With this leap towards the global, the targets of citizen mobilisations and protests were broadened. If, traditionally, they had set their sights on national institutions (or, in some cases, sub-national), after 2000 opposition was also aimed at certain supranational organisations (G8, the Davos Forum, the IMF) and transnational companies like Nike and Amazon.21 At present, it should be noted that technological innovations have enabled new forms of protest (for example, technological activism, cyberattacks, and information leaks) and have also provided a privileged channel for social mobilisation.22

Along with studies on political participation, the second relevant field of analysis of protests is that of social movements. Without a doubt, protests are the ‘most tangible expression of a social movement’.23 From this area of study, it is indicated that, unlike other social and political activities, protests are, by nature, a complex phenomenon, conceptually ambiguous, and with no fixed definition.24 For the German sociologist Karl-Dieter Opp, protests are the ‘joint (i.e., collective) action of individuals aimed at achieving their goal or goals by influencing decision of a target’.25 Accordingly, they can be defined as political claim-making acts that are notable for a strong communicative vocation in the public sphere. With regard to understanding this social phenomenon, the sociologists Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow have made a vital contribution with concepts like ‘contentious politics’, which is understood as

‘episodic, public, collective interaction among makers of claims and their objects when (a) at least one government is a claimant, an object of claims, or a party to the claim and (b) the claims would, if realized, affect the interest of at least one of the claimants’.26

Protests can take place through various types of actions, from peaceful demonstrations through to acts of violence. Hence, to return to the theoretical proposal of Barnes and Kaase, the forms in which they are manifested range from activities of a conventional nature (collecting signatures for petitions, demonstrations, marches, rallies) to non-conventional activities (blocking streets or buildings, strikes, occupations, acts of violence, and arson).27 Furthermore, protests can be isolated or multiple. In the latter case, they are referred to as a wave of protests and, if after some time, they are renewed, it could be the onset of a cycle of protests, which tend to be typified as outbreaks of protests and a receding of waves of protests.28 Faced with this situation, the state can respond in different ways: allowing the protests, clamping down, and granting concessions in response to the demands of the more moderate actors while repressing the more radical ones. It should be emphasised that a cessation of protests does not necessarily mean the end of mobilisations. It could simply mark the beginning of a shift towards conventional forms of political mobilisation, which is to say those that remain within the framework of the legal and political channels established by the existing institutional system. By contrast, it might also happen that peacefully expressed mobilisations become wholly or partially radicalised. As for demands, protests are not always based on the formulation of political demands (whether by means of conventional or confrontational mechanisms). At times, they can lead to self-management or self-provision of goods through a broad range of actions, including community-based strategies, alternative lifestyles, mutual aid, and social provision of services.29

Since the end of the 1960s, expressions of social unrest have mainly occurred in urban settings. The events of May ’68, the Hong Kong protests of the 1980s, the anti-globalisation mobilisations of the late 1990s, and the protests of 2011 (among them Tahrir Square in Cairo, Puerta del Sol in Madrid, Gezi Park in Istanbul) are just a few examples of the role that cities presently play as spaces of political action. The relationship between cities and contentious politics has been studied in the social sciences since the first urban protests at the end of the 1960s, thus prompting the emergence of a new analytical field, namely urban social movements. Its main theorists have explored such concepts as production of space, urban conflict, and transnational organisation of urban movements.30

It should be noted that, historically speaking, the growth of urban mobilisations is related with the patterns of economic development that have prevailed on a worldwide scale since the 1980s, profoundly shaping urban planning and the political economy of cities. The shift from the modern industrial city to the post-industrial global city has turned urban space into a strategic node from which the global economy is structured. This, in turn, has imposed a certain urban model (‘new urbanism’, to use the term employed by Salet and Gualini31) that is characterised by the development of large-scale urban renewal projects and promotion of political strategies aimed at making cities attractive environments for international investment. These dynamics have also involved problems like the privatisation and commodification of cities and, as a result, increasingly restricted access to housing, gentrification, and displacement of low-income earners. In these circumstances, urban protests should be interpreted in terms of the complex interlinking of these local-global processes.

Key global trends of social unrest

Global trends from 2011 to 2018

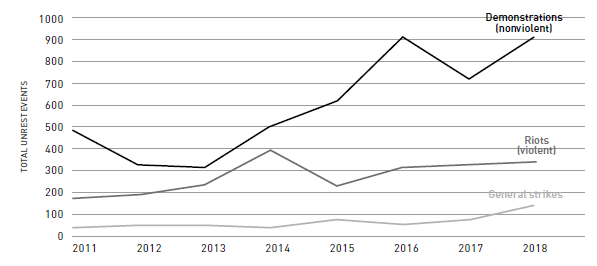

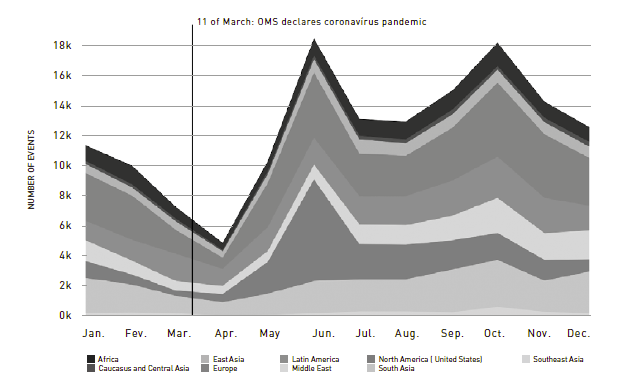

According to recent data, the last decade (2011-21) has been marked by rising levels of social conflict, basically as a consequence of the recession stemming from the global economic crisis of 2008, and the impact of the austerity policies imposed by governments.32 As figure 1 shows, the main expressions of social unrest were manifested in 2011 as part of the wave of Arab Spring protests which, after 2012, diminished in intensity, either because they had attained their goals, or had been crushed by government forces, or had escalated into civil war. Nonetheless, the Arab Spring was not the only expression of social unrest. Demonstrations and protests were increasingly numerous until reaching a high peak in 2016 and then again in 2018-2019.

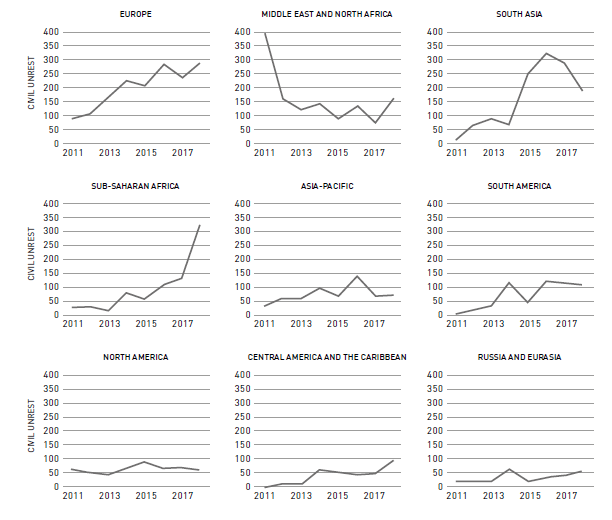

Naturally, not all the regions of the world followed the same pattern. The highest levels of protest in the years from 2011 to 2018 were recorded in Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia (see figure 2). As for the kinds of protests, contrary to widely held beliefs, the majority were peaceful (see figure 1), as in Europe where 65% of the events recorded were non-violent. Here, the most notable protests occurred in Greece (because of structural adjustments imposed after the global financial crisis), the United Kingdom (in response to austerity policies and housing problems), France (gilets jaunes or ‘yellow jackets’), and Spain (the indignados movement and, after that, the conflict over Catalonia’s bid for independence).

Sub-Saharan Africa, however, is the subregion with the world’s highest levels of violent demonstrations (42.6%). In the period analysed, these protests grew exponentially after 2015. The countries recording the most serious unrest were Nigeria (mainly due to the imprisonment of Ibrahim Zakzaky, leader of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria), South Africa (largely as a result of rising university fees), Ethiopia (tensions between the federal government and that of Oromia State where the capital, Addis Ababa is located), and Guinea (broken promise of pay rise for teachers, and protests over fraud in local elections). In South Asia, the countries recording the highest levels of social mobilisation were India (general strikes) and Pakistan (anti-government protests). As shown in the next section, these two countries have headed the list in terms of social unrest since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The regions with the lowest incidence of social disturbances were North America, Central America and the Caribbean, the Asia-Pacific, and Russia-Eurasia. While the trends in the above-mentioned regions (Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia) have remained the same except for subtle variations since the onset of the pandemic, in these latter regions, the pattern diverges significantly (except in the Asia-Pacific region). In 2020-21, North America, Central America and the Caribbean, and Russia-Eurasia were among the countries with the greatest numbers of social protests and mobilisations, a situation which will be described in more detail below.

The protests of 2019, interrupted by COVID-19

As figure 1 shows, 2018 ended with an upward trend of social unrest which continued to rise in 2019, a year in which the world witnessed a generalised increase in the number of protests with some especially important flashpoints.35 Notable among these are the ‘yellow-jacket’ protests in France, which had begun at the end of 2018, those in Hong Kong in protest against the proposed extradition bill and, in India, against the Citizenship Amendment Act. In Latin America, the mobilisations swept through several countries, including Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Bolivia. In Chile, the population mobilised against the increased price of public transport in protests that later extended to demands for a new constitution. In Colombia, the protests against President Iván Duque took aim at his economic, social, and environmental policies, as well as his handling of the peace agreement between the government and FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). In Mexico, there was a major wave of feminist protests.

Notable in the Middle East were protests in Iran, Iraq, and Algeria. In Iran, the social unrest arising from increased fuel prices spilled into months of demonstrations against the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In Iraq and Algeria, citizen uprisings destabilised both countries to such an extent that, in the former case, President Barham Salih and his prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi, and in the latter, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika (after twenty years in power) were forced to step down. Especially notorious in Africa were the demonstrations in Sudan which, demanding a democratic transition, ended up with a coup d’état against President Omar al-Bashir. As shown in the following section, these dynamics ended with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent government restrictions on mobility and social activity in the public space.

Social unrest in the COVID-19 era

Global trends in 2020 and 2021

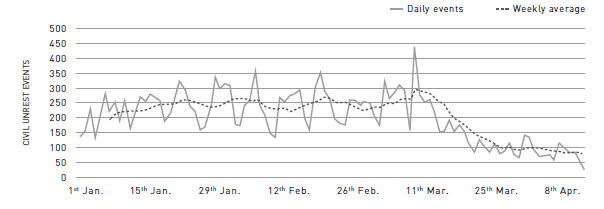

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. In the early months of 2020, the number of social demonstrations dropped by 30% although, immediately afterwards, the figure rose by 7% in comparison with 2019.36

The pandemic has sparked a good number of protests while also intensifying others that already existed. The first kind of protests, expressed on the streets, rejected restrictions (Germany, United States), called for better public health management of the pandemic (Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico), and demanded economic support (South Korea, Japan).

Nevertheless, it was not long before the pre-pandemic protests were revived (see table 2). After the interruption, their original grievances were exacerbated by the impact of the health crisis. In countries like Israel, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Tunisia, the pandemic had aggravated earlier problems related with government corruption and the general economic situation. Likewise, in Chile and Peru the pandemic has given rise to numerous workers’ demonstrations. In Iran, the social unrest resulting from corruption, deficient public services, and economic hardship has been compounded by the pandemic. In Argentina, social dissent over the abortion law was fuelled by widespread criticism of the government’s healthcare management and the negative impact of the crisis on the economy. Something similar occurred in Serbia, where there was significant unrest over alleged electoral fraud. Neither did the pandemic stand in the way of anti-government protests in Belarus. As for the violent or peaceful nature of these expressions of social dissent, approximately 93% were peaceful. Even so, some 16% were met with police repression, especially in Belarus.37

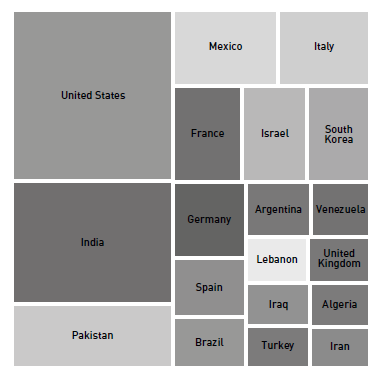

The exception in this context of global increase in protests was Asia, where the region as a whole registered a downward trend. However, and despite the general pattern in the region, two of its countries were among those showing the highest numbers of protests in 2020, namely India and Pakistan. However, globally speaking, the country with the higher number of demonstrations of political unrest was the United States with almost as many protests as these two countries combined.

Trends in the Atlantic region: America and Europe lead

The world in social protests

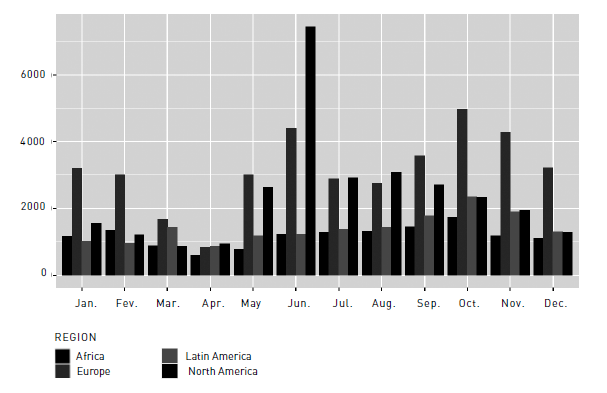

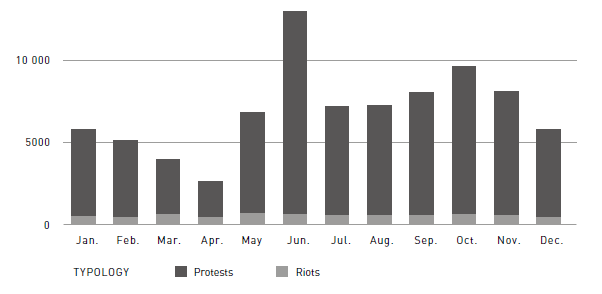

As figure 6 and figure 7 show, the Atlantic region concentrates a large part of the social unrest recorded in 2020, especially in the regions of North America and Europe. A closer look at the trends of social unrest in these geographical areas reveals two notorious features: first, the demonstrations were eminently peaceful; and, second, the United States clearly leads in terms of the number of protests. The murder of George Floyd, a Black American who was choked to death by a white police officer in May 2020, marked a turning point in terms of social unrest due to the wide mobilisation of the anti-racist movement Black Lives Matter (BLM).

Figure 7 > Evolution of social unrest in the Atlantic region in 2020. Source: ACLED. Figure by F. Teodoro.

Figure 8 clearly shows an exponential rise in the number of protests between May and June 2020 due to Floyd’s murder and the subsequent revitalisation of BLM causing the highest levels of protest ever seen in the country.

Figure 8 > Evolution of protests in the United States from February 2020 to June 2021. Source: ACLED. Figure by F. Teodoro.

The magnitude of the BLM wave of protests is explained not only by the problems of structural racism in American society and the police violence unleashed against the Black American population but also by two additional (and interrelated factors) that help to explain the repercussion of the BLM protests around the country: first, the Black population comprises the social sector that has been most affected by COVID-19 contagion and deaths; and, second, the health crisis has had a greater economic impact on this population whose jobs and salaries are more precarious than those of white Americans. It was in this context that the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer sparked the collective indignation of anti-racist groups. These events were not unprecedented in American history. As studies in the field show, some of the most significant protests in the United States (for example, those led by the civil rights movement) were triggered by episodes of police or state violence.39 One well known example is the 1967 Newark riots which began on 12 July when a Black cab driver was brutally beaten by two white police officers, thus setting off a wave of disturbances in Newark, New Jersey, Atlanta, Boston, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, Rochester, and Minneapolis.

The revival of the BLM movement after May 2020 was answered by multiple counter-protests organised by American far right groups at a time when they had come to prominence during the administration of Donald Trump. These extremists also organised the pro-Trump Stop the Steal movement that appeared in the framework of the presidential elections and culminated with the storming of the Capitol in January 2021. As a result of this situation of social polarisation with anti-racist and extreme right protests, the United States now heads the list of countries with the highest numbers of episodes of political unrest not only in the Atlantic region but also the entire world.

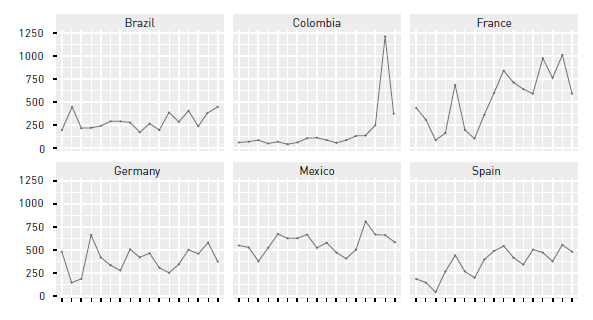

Coming second to the United States, the Atlantic country recording the highest number of protests is France, followed by Mexico, and then Germany, Spain, and Brazil (see figure 9). It should be borne in mind when comparing the intensity of social unrest in the United States and these other countries that the scales used in figures 8 and 9 to represent the numbers of protests in the former and latter cases are significantly different. In the case of the United States, it has been necessary to use a graph capturing between 0 and 6,000 events, while for the other Atlantic countries showing the highest incidences of social unrest (France, Mexico, Germany, Spain, and Brazil), the scale used is 0 to 1,250 events. As a result, the intensity of the protests in the case of the United States escapes even the general trend of the region with the highest number of protests worldwide. Of course the demographic characteristics of the United States partly explain the reason for these differences.

With regard to the causes of the protests in France and Mexico, the reasons differ considerably. In France, protests triggered by the pandemic (see table 2) have predominated, especially in the form of rejection of the measures adopted by Emmanuel Macron’s government (rejection of vaccination, the health passport, etcetera) in their attempt to manage the health crisis. In addition to these reasons, the murder of George Floyd in the United States prompted anti-racist protests in several French cities, as also occurred in many other cities across the world. In France, Floyd’s murder revived the memory of Adama Traoré, a twenty-four-year-old man of Malian descent who also died in police custody, in 2016. Also noteworthy were the large-scale protests at the end of 2020 against a new security bill by means of which the government sought to ban images of police officers in the mass media and social networks in order to protect their identity. The bill even prompted a response from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, who considered that it undermined basic human rights.

As for Mexico, protests by feminist groups are especially noteworthy. Plagued for decades by the problem of femicide, the country has seen the rise of a new generation of young feminists who have decided to break the silence and place the issue on the political agenda and in the mass media. They mainly use social networks, which has not prevented them from also taking to the streets in order to protest, a combination of tactics that has been called ‘fourth-wave feminism’.40 There have also been mobilisations by student groups calling for improvements in education and a more equitable system, protests against police violence, and marches organised by Indigenous peoples demanding rights and greater political recognition.

COVID-19 and cities

COVID-19, an urban pandemic, in the Atlantic region as well

UN data on the global incidence of COVID-19 reveal that it is essentially an urban phenomenon. Approximately 95% of infections and deaths have occurred in cities, affecting some 1,500.41 The link between pandemics and cities is not new.42 Indeed, there is a historical relationship between cities and epidemics that explains a considerable part of urban development over the last two centuries. City spaces, as dense urban fabrics with high concentrations of people living and working together, have provided a perfect medium for the transmission of contagious diseases and, hence, the irruption of plagues and epidemics. Each serious public health episode has led to a revision of the urban model with the aim of assuring the necessary hygiene and sanitation of cities. The first attempts to provide safe urban spaces ranged from engineering works designed to give access to drinking water, managing waste, and creating a sewage system, to the construction of parks, promenades, and public squares. From the 1918 influenza pandemic to the swine flu pandemic of 2009 (both caused by the H1N1 virus), cities were laboratories where public health solutions were tested. Hence, it can be stated that the contemporary city, as we know it today, has been shaped by the impact of infectious diseases.43

According to the forecasts, this link between pandemics and cities will only become more pronounced in the future. The current situation of global urbanisation is associated with changes in land use and the consequent destruction of natural ecosystems, which increases the numbers of disease-carrying animals like rats, bats, and mosquitos. In this regard, cities surrounded by agricultural lands are more likely to be affected by infectious diseases because the transformation of wilderness areas into peri-urban agricultural land inevitably makes them more susceptible, as recent studies have shown. For example, more than 60% of the new infectious diseases come from wild animals. This situation is compounded by a high degree of global connectivity, and hence, an easier spread of diseases on the planetary scale.

Given the link between cities and pandemics, it is relevant to raise the second research question of this study with the aim of establishing the role of urban settings in the pandemic-protests-inequalities equation. In seeking to respond to this question, I shall provide a summarised account of data pertaining to cities with the highest numbers of protests in the three Atlantic countries showing the highest rates of social conflict, namely the United States, France, and Mexico. It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore in detail the phenomena of social unrest in each of the cities (the demands, the groups that are mobilised, protest methods, and so on). I shall only offer a brief overview that will identify some of the main trends. It remains for future research to explore these issues in greater depth and consider them in the light of earlier research on urban protests.44

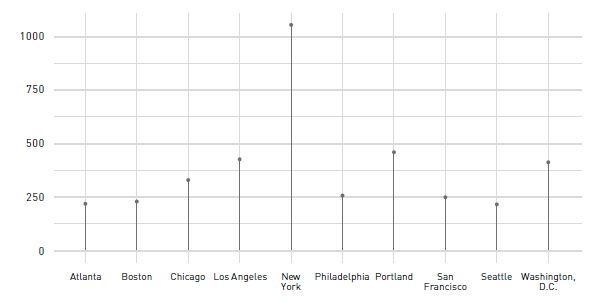

In the United States, the cities most affected by expressions of social unrest in the COVID-19 era are those shown in figure 13, with New York in the lead (1,054 protests), followed by Portland (459), and Los Angeles (428). It is not surprising that the country’s most populous city with 8.5 million inhabitants should top the list. However, why Portland, with just over half a million inhabitants should occupy second place, ahead of Los Angeles with almost four million inhabitants, is not so obvious. If these data are compared with those that will then be analysed for France, it even emerges that Portland presents a level of social conflict that is comparable with that of Paris with four times its population. The explanation lies in the social mobilisations in response to the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Although Portland’s Black population numbers just over 5% of the total, the city has a well-organised anti-racist movement which, added to a decades-long tradition of social mobilisation (Occupy movements, feminist struggles, anti-Trump groups, inter alia), accounts for the many expressions of social unrest in this city.

Figure 10 > Protests in US cities from February 2020 to June 2021. ource: ACLED. Figure by F. Teodoro.

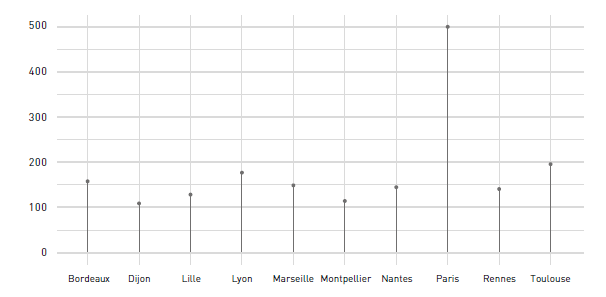

In France, Paris (2.2 million inhabitants), with the highest number of protests (503) shows a significantly higher incidence of social unrest than other cities. Toulouse and Lyon showed much lower figures (195 and 178 protests respectively), but their high concentration of protests in relative terms is explained by the fact that they are two of France’s largest cities after Marseilles.

Figure 11 > Protests in French cities from February 2020 to June 2021. Source: ACLED. Figure by F. Teodoro.

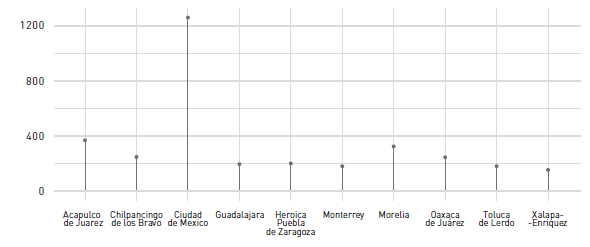

In Mexico, Mexico City (9.2 million inhabitants) stands out with more than 1,257 protests. In absolute terms, this is the city that has presented the highest level of social conflict for all three countries in the period analysed. Far behind the capital are Acapulco de Juárez (369), Oaxaca de Juárez (250), and Chilpancingo de los Bravo (248). Paradoxically, it would seem, the two latter cities are among those with the smallest urban populations (less than 300,000 inhabitants). However, they are both located in states (Oaxaca and Guerrero) that are traditionally known for the high degree of political organisation of their populations. For decades now, Oaxaca has been the scene of many mobilisations (peasants, students, Indigenous groups, and neighbourhood associations), while the state of Guerrero has a highly active student movement which has been faced with police massacres, torture, and disappearances of its young members.

Figure 12 > Protests in Mexican cities from February 2020 to June 2021. Source: ACLED. Figure by F. Teodoro.

After this brief overview of the cities that have had the highest numbers of protests in the three Atlantic countries showing the greatest social conflict, I shall discuss the impact of the pandemic in the urban sphere with a view to better understanding how it has affected inequalities. Has it created new problems or, rather, aggravated already existing ones?

Pandemic and (urban) inequalities

In urban settings, COVID-19 has exposed a series of structural vulnerabilities which the pandemic has only exacerbated. In particular, these weak points are related with poor access to public health systems, precarious housing and employment, and lack of drinking water and basic sanitation infrastructure in some parts of the world.45 With these underlying problems, guaranteeing the right to health is a goal that is not always attained for some people. Contrary to the belief in the early days of the pandemic that ‘the virus will affect everyone equally’, its incidence has been much higher in certain population groups. In an article published in Public Health, doctors from several British universities have argued that people of low socioeconomic status are more vulnerable to COVID-19 for several reasons: i) they are more likely to live in overcrowded dwellings and in poor housing conditions (badly ventilated and with little access to outdoor space); ii) they tend to be employed in occupations with few opportunities for working at home, which means that it is difficult for them to reduce their mobility; iii) their work and income conditions are likely to be unstable, which can have negative effects on their mental health and thus on their immune systems; iv) they present at healthcare services with more advanced stages of illness, and will therefore have poorer health outcomes; v) they face certain problems like language barriers, discrimination, disrespectful attitudes, and so on, which makes them feel less comfortable about going to health centres; vi) they suffer more from hypertension and diabetes, which are both risk factors for COVID-19.46 It therefore seems evident that there is a clear link between higher negative incidence of the pandemic and inequalities.

The problems listed above are frequently related with pre-existing spatial disparities, expressed in problems of residential segregation, and poor access to basic services and decent housing, which would explain why some neighbourhoods have higher infection rates than others.47 Some urban zones are mainly populated by people of a certain socioeconomic profile and social groups that are traditionally discriminated against (migrants, racialised communities, ethnic groups), amongst whom the pandemic has seriously worsened their living and health conditions, with concomitant high mortality rates. Although data disaggregated by gender, ethnicity, and race are still incomplete or imprecise, the first studies to appear in the United States showed that that Black Americans were dying at a much higher rate (3.5 times more) than white Americans.48 In April 2020, for example, 70% of the COVID-19 deaths in Chicago occurred among the Black population, which represents only 29% of the total population of the city49. In the same period, the Black population of Michigan (14%) accounted for 40% of COVID-19 deaths.50

The pandemic has therefore accentuated already existing inequalities and, according to the forecasts of international organisms, these will only get worse in the years to come. While low-income countries with longstanding weak economies and structural social inequalities are in very challenging situations as a result of the pandemic, the World Bank predicts that middle-income countries will be especially affected by the emergence of a group dubbed the ‘new poor’ because of the effects of COVID-19. It is estimated that eight out of ten of the ‘new poor’ will come from these countries and that the number of people living in extreme poverty will rise to 150 million by the end of 2021. This group mostly lives in cities and urban areas.51

Conclusion: pandemic, (urban) inequalities and social unrest, a causal relationship?

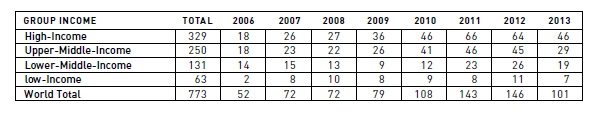

In the above section, I have noted the link between pandemics and inequalities and sought to highlight the fact that the latter are especially expressed in cities. Is there, then, any correlation between inequalities and social unrest? Judging from the empirical data I have analysed here, this does not seem so clear. In fact, the countries with the highest numbers of protests in 2020 (United States, France, and Mexico) are not low-income countries (which, presumably, are more affected by problems of inequality) but middle- and high-income countries.52 An earlier study on global protests between 2006 and 201353 came to similar conclusions after analysing almost 900 expressions of social unrest in multiple countries around the world (see table 3). High-income countries showed the highest concentration of protests, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. However, violent protests occurred in low-income countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. As I have suggested above, this trend continues to the present day. This result means that any interpretation of the causal relationship between social unrest and inequality must be complex. In other words, countries with higher levels of inequality do not necessarily have more social protests. Nevertheless, there does seem to be a link between violent disturbances and low-income countries.

Why, in the Atlantic region, do the United States, France, and Mexico, show the highest indices of social unrest when they are high- and middle-income countries? Several factors help explain this phenomenon. First, are those of a historical nature. The United States, Mexico, and France were leading revolutionary centres from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, so some aspects of their political culture would probably explain why their populations are more likely to engage in political mobilisation than those in other geographical settings. In Latin America, moreover, there is a long tradition of civil society mobilisation, which could also account for the fact that, while it is a continent with mainly middle-income countries, it tends to be the locus of more protests than countries in other parts of the planet that might be comparable in terms of income. Furthermore, generally speaking, high- and upper-middle-income countries tend to have less repressive governments, better educational opportunities, and greater capacity for civil society organisation. The study by Ortiz et al. comes to similar conclusions.

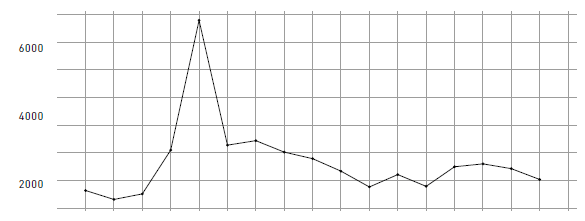

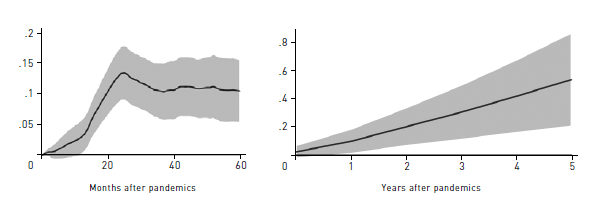

If the link between inequalities and protests in the COVID-19 is not immediate, as this study seeks to show, it is important to distinguish between the short- and long-term impacts of the pandemic. In the short term, it is clear that, by and large, there is no causal relation between greater inequality and more social protests. Yet, it is possible that, in the medium and long terms, middle- and low-income countries could see considerable increases in levels of mobilisation as a direct consequence of problems caused by the pandemic. According to United Nations data, cities in low-income countries will face the most difficult situations as they have the highest malnutrition rates, greater comorbidity, and deficient public health systems.55 Given these problems, in addition to low public spending on health (in low-income countries this was $41 per capita by comparison with $2,937 in high-income countries,56 it is easy to imagine a significant rise in urban social unrest. The IMF, too, expects that there will be increased social conflict, even venturing that, ‘social unrest increases about 14 months after pandemics on average. The direct effect peaks in about 24 months post-pandemic’.57 According to this forecast, we can expect an upsurge in protests around the world from May 2021 to March 2022. We are, then, at a crucial point in history. The extent to which policy makers are aware of this is another matter. Nevertheless, they have the means to adopt the necessary policies and means to forestall social unrest which, in all likelihood, will increase over the coming months and could stand in the way of post-COVID-19 reconstruction.

Figures 13 and 14 > Impact of the pandemic on social unrest. Source: Tahsin Saadi Sedik and Rui Xu.58