Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tékhne - Revista de Estudos Politécnicos

versão impressa ISSN 1645-9911

Tékhne n.13 Barcelos jun. 2010

Socially responsible behaviour: Labour market in Portugal

Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão of Instituto Politécnico da Guarda

Abstract

New laws and changes related to the labour market, especially in the European Union context, have generally had positive effects, as they have also benefited economic, social and political development. Based on Portugals experience, these constant changes should be prevented as well as possible in order to better counter any negative consequences that might ensue. One of these consequences is critically examined and it is related with the fact that people do not want to work or want to work as little as possible. In such an environment, firms face a difficult labour problem. The facts and statistics justify the need for a proactive attitude in order stimulates people in both the public and private sector to work and develop skills has become urgent. Furthermore, since work is often a result of voluntary initiatives undertaken by individuals, the interventions undertaken by policymakers that promote social welfare and poverty eradication for a large majority of the population, can result in a disincentive.

INTRODUCTION

Socially responsible behaviour (SRB) has attracted a great deal of attention over the past decade. This issue gains relevance when the focus is on the labour market and it generates intense political debate in Europe given the openness and flexibility of the labour market in Europe. In addition to a simultaneous emphasis on multiple forms of SRB, a large number of firms appear to be increasingly engaged in a serious effort to define and integrate SRB into all aspects of their economic activity, despite increasing uncertainties in the labour market.

These uncertainties rise as a consequence of new laws and constant changes within the labour market. These changes are, especially in the European Union context, generally positive in their effects, as they have benefited economic, social and political development in Portugal. This is especially true with regard to the creation of employment opportunities, employment protection, social security, unemployment insurance, and other labour policies. However, based in the Portugals experience, constant change should be prevented and it must be managed as well as possible, with view to counter its negative consequences.

Historically, labour market development in Portugal experienced three phases. The first phase began with the cessation of the dictatorial regime of Salazar (in 1974) and the introduction of active participation of workers in the firms management and the negotiations of employment conditions at work. The outcome of this phase was the adoption of policies that could be comparable with other European countries. The most important policy that meets these criteria was the establishment of a national minimum salary, the statutory enforcement of the number of weekly hours of work, and the approval of a labour code.

The second phase began with the accession to the European Economic Community (in 1986) and the transformation from a manufacturing (and agriculture)-based economy into a service-based economy, followed by the privatisation of key State-owned firms (Paulino, 2000). The outcome of this phase shows a wide range of publicly funded schemes adopted in order to stimulate and support the expansion of employment and economic activity.

The third phase began with the economic recession (in 2000), which has been introducing remarkable changes in Portuguese firms and in society, such as: early retirement, further education, retraining, new weekly hours of work and the reduction of wages. The outcome of this phase remains unclear, because this phase will only end when the next phase begins. Only then will it be possible to identify the indicators and employment policies that would render the labour market successful.

In Portugal, governments have developed and implemented intensive education, technology and labour policies to promote equal opportunities, economic growth and social integration, in a sustainable development framework. Thus, these polices have been introduced with the main objectives of producing economic changes and technological improvements. Despite the weak resilience of economic activity, the deceleration in employment in 2001 and 2002 was relatively limited when compared with that observed in the past for similar activity growth profiles (BP, 2002). However, these actions faced social traditions that conditioned and limited their application.

In general, the Portuguese labour market is characterized by a high degree of collective bargaining power as a result of unionization. In particular, all the Portuguese union structures are based on the criterion of solidarity. It is important to explain that the conceptual basis of the freedom to unionize meets with the rules and guides of the International Labour Organization. During the last period of changes, the bargaining power of trade unions has declined at both the national and international levels. Nevertheless, trade unions still play an important role in wage determination in the public sector and in large privatized companies in Portugal. On the other hand, in the private sector, trade unions have almost disappeared. Despite this, trade unions have retained their influence in the creation of new labour legislation through negotiations and coordination with employer associations and the government.

The remainder of this research is organised as follows: The next section puts the socially responsible behaviour in perspective, that is, it analyzes the contribution of firms behaviour towards sustainable economic development and labour market progress. The third section describes the labour market in Portugal in the context of a qualified and trained workforce. Next, the fourth section analyzes economic and social development in Portugal, especially after the accession to the European Economic Community in 1986. During this time, given the inherited corporatist culture, prominence was given to the law and the government policies concerning other forms of regulation. Finally, the last section presents some comments that contribute to the debate about socially responsible behaviour in the Portuguese labour market.

SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE BEHAVIOUR

The concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is explained in the Green Paper (EC, 2001a: 4) a follows:

a concept whereby companies decide voluntarily to contribute to a better society and a cleaner environment,

The Communication from the Commission of the European Communities, about Corporate Social Responsibility: A business contribution to Sustainable Development (EC, 2002: 3), defines the concept as:

a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis.

It is our view that CSR is a voluntary commitment that goes beyond legal obligations. In this sense, firms contribute to sustainable economic development through their support of ethical and moral principles.

However complex, socially responsible behaviour can provide important signals about corporate social responsibility activities. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) promotes policies

to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy (OECD, 2001: ii),

as defended article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris in 1960. Despite the fact that economic activity is constantly changing, this policy is very timely. However, it still has a long way to go in order to achieve complete fulfilment.

More convincing evidence that SRB may affect labour relations comes from the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights, Mary Robinson who states:

business decision can profoundly affect the dignity and rights of individuals and communities it is not a question of asking business to fulfil the role of Government, but asking business to promote human rights in its own competence (OECD, 2001: 13).

Over time, the incorporation of fundamental rights of workers has enabled labour law reforms. The debate concerning institutional reforms has stimulated the distribution of information and the notion of socially responsible behaviour to the extent that it has become commonplace. This debate is also associated with the need to understand the perspectives that influence this commitment. So, judging from this commentary, the authors believe that since firms are becoming more socially responsible, this will improve labour relations. Consequently, workers rights can be ensured and good relationships with managers guaranteed.

These arguments become particularly persuasive in a situation where several institutions, all over the world, promote socially responsible behaviour in the labour market. A good example was the United Nation Global Compact (UN, 2008), proposed by the Secretary General of the United Nation. It is a purely voluntary initiative and provides a framework for businesses that are committed to aligning their operations and strategies with ten universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights (two principles), the environment (three principles) anti-corruption (one principle), and labour standards (four principles).

Related to the labour market, the third principal, namely to uphold freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining of the United Nation Global Compact (UN, 2008) needs to be reflected in employment policy and legislation in general. For example, in Portugal, as observed in Table 1, below, the number of agreements published by the Labour Ministry demonstrates a dramatic fall in collective bargaining as a result of considerable pressure to make labour market more flexible.

Table 1 – Collective agreements, 2000-2004

|

| Unit | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

| Collective agreements | number | 371 | 361 | 338 | 342 | 162 |

| Workers covered | thousands | 1,453 | 1,396 | 1,386 | 1,512 | 600 |

| Average duration | months | 16.9 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 14.1 | 17.1 |

Source: Lima & Naumann (2005: 1).

Table 1 shows that, in 2004, the lower level of the number of workers covered by these collective agreements fell to less than half the level recorded for 2003. This negative trend was particularly pronounced at plant level. Fernandes (2002: 1) considers that:

the individual trade unions and employers associations are too numerous to mention (more than 300 of each) and they thus have relatively small memberships, limited financial resources and a limited ability to take assertive action.

In addition to and related to labour relations and employment practices, the four principles of the UN Global Compact and the Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, published by the OECD (OECD, 2000: 21), provide that firms should:

a) Respect the right of their employees to be represented by trade unions and other bona fide representatives of employees, and engage in constructive negotiations, either individually or through employers associations, with such representatives with a view to reaching agreements on employment conditions;

b) Contribute to the effective abolition of child labour;

c) Contribute to the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

d) Not discriminate against their employees with respect to employment or occupation on such grounds as race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction or social origin, unless selectivity concerning employee characteristics furthers established governmental policies which specifically promote greater equality of employment opportunity or relates to the inherent requirements of a job.

In order to explore the nature of the labour market and social responsibility, the Ministry of Labour and Social Solidarity was created in Portugal in 1916. It is now known as the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare. Several years have passed since its creation and therefore it is now possible to observe that the Ministry has and still is engaging in socially responsible actions, such as the provision of social welfare and the encouragement of solidarity. The general policy objective is to improve the living and working conditions of every citizen. The means to achieve these objectives are national legislation, and also to a large extent, agreements concluded by the social partners at all levels.

To materialize these objectives, the Portuguese government, represented by the Labour Ministry, is involved in the labour market and the industrial relations system on four main fronts: as lawmaker, manager, judicial authority and employer. The duty of lawmaker of the Ministry includes extended obligations, such as overseeing the orientation and practice of the labour and employment policies promulgated by the Ministry, the provision of professional training in labour law and social security, the provision of social security as well the rehabilitation of disabled people. To promote the achievement of these objectives, the Minister is assisted by the Secretary of State of Social Security, the Secretary of State of Employment and Professional Training, and the Secretary of State Adjunct and for Rehabilitation. Also, the Ministry has integrated several services under the direct administration of the State. These services are undertaken by organisations under the superintendence and tutelage of the State and consulting organisations. Examples include the Authority for Working Conditions and the Institute for Financial Management of Social Security. All these institutions and policies have the main objective of obtaining a favourable (although it is sometimes critical) public image.

Furthermore, the labour market policy in Portugal supports employment creation, qualification measures, social development and gender equality (Moniz & Woll, 2007), based on the promotion of social welfare that requires that certain values and ethics be reflected in the behaviour of individuals, firms and society in general. Indeed, the economic survey of Portugal 2008 confirms that Portugal requires an improved business environment and a more flexible labour market in order to promote job creation and labour mobility. Therefore, reforms aimed at enhancing the adaptability of the labour force are needed (OECD, 2008).

The rights of the workers are based on a body of legislation that defines the rights and obligations of workers and employers in the workplace. In other words, the government guarantees certain rights and obligations and working conditions in the employment relationship. However, it seems that industrial relations and higher education play an even more pivotal social responsibility role in society. The European Commission (EC, 2001b: 7-8) emphasised this fact when it stated that:

( ) the employability and adaptability of citizens is vital for Europe to maintain its commitment to becoming the most competitive and dynamic knowledge based society in the world.

Furthermore, it is not possible to focus on the labour market, without making reference to the International Labour Organization (ILO) which was founded in 1919. In 1946, it became the first specialized agency of the UN. A central and contentious discourse in the literature concerns the pursuit of a vision based on the premise that universal, lasting peace can only be established if it is based upon decent treatment of working people. In order for the work of the ILO to gain relevance, its objectives must be promoted by governments, firms and citizens. Key to this is the implementation of the stakeholder theory approach and in addition to that, the enforcement of socially responsible behaviour through laws, regulations, standards and codes of conduct.

In 1944, the International Labour Conference adopted the Declaration of Philadelphia, which redefined the aims and purpose of the ILO, based on the following principles:

- Labour is not a commodity;

- Freedom of expression and of association are essential to sustained progress;

- Poverty anywhere constitutes a danger to prosperity everywhere;

- All human beings, irrespective of race, creed or sex, have the right to pursue both their material well-being and their spiritual development in conditions of freedom and dignity, of economic security and equal opportunity (ILO, 2003: 5).

In contrast, conventional economic logic suggests that, ceteris paribus, in counties where regulation does not exist and is neither enforced, workers could face discrimination and all forms of forced or compulsory labour. The conflicting nature of the above arguments suggests that the most important of the above-mentioned principles is that labour is not a commodity. Its importance lies in the fact that it can serve as a basis for society to be fair and then to promote measures, laws, codes and regulations which must be implemented so as to promote socially responsible behaviour.

Furthermore, the absence of rights to unemployment benefits and the unequal distribution of employment between men and women are some of the ethical problems that many societies face as a consequence of profound political, social and economic transformation. However, at the same time and paradoxically, is possible to confirm, as David & Abreu (2008: 362) have, that:

the increase of an ethic sense; that is to say that society and firms, as well the citizens, increasingly recognize the importance and the value of ethical and socially responsible behaviours, as well as the risks and costs that the deviations from ethical ideal involve..

THE LABOUR MARKET IN PORTUGAL

Despite the existence of an enormous body of laws, regulations and codes that have emerged and been enforced reform is necessary. As Rodríguez-Piñero (2005: 2) argues:

Portuguese labour law has its origins in the interminable authoritarian period the country underwent, when regulation of the main labour market institutions was developed and consolidated. This experience shaped employment legislation in its entirety so that a far-reaching reform process was needed with the advent of a democratic regime.

The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic (AR, 2005) which was enforced in 1976, contains declarations of principles and more effective rules to regulate the labour market. This framework is largely utilised in case-law. Examples include the enforcement of fair pay, maximum weekly hours of work, weekly and annual paid vacation, the protection of women and of minors at the workplace, the provision of social insurance for old age, illness, invalidity, industrial diseases and accidents, the enforcement of freedom of association and right to strike.

These important changes did not stop with Constitution. In the course of the last 32 years there has been extensive pressure to make labour legislation more flexible. This has led to consistent reforms especially since the accession to the European Economic Community in 1986. All these changes aim at ensuring reasonable protection for workers and, at the same time, encouraging the government, various institutions, firms and society in general to be more adaptable to technical and organizational change, and to focus on socially responsible behaviour.

Without doubt, the third chapter of the Portuguese Constitution which deals with rights and freedoms of workers is the most important. It has several articles. For example, article 54 deals with workers' committees, article 55 deals with trade union rights, article 56 deals with collective agreements, and article 57 deals with the right to strike and prohibition of lock-outs. In addition, article 53 which is dedicated to employment security provides:

The right of workers to security of employment is guaranteed. Dismissals without just cause or for political or ideological reasons are prohibited (AR, 2005: 4650).

Workers currently rank as a strategic variable, permitting the development of competitive factors based on innovation, management and technology. Consequently, it is a reality that firms are dependent on workers for their existence. These workers represent several groups of interests or stakeholders, with different particularities and relationships. So, the collective process of change behaviour should be based on the sustainability, transparency, accountability and social contract principles of CSR proposed by Crowther & Rayman-Bacchus (2004: 239), because they are:

concerned with the effect which action taken in the present has upon the options available in the future. If resources are utilised in the present then they are no longer available for use in the future, and this is of particular concern if the resources are finite in quantity.

In order to address economic concerns Portugal has introduced major labour legislative packages, i.e., unemployment insurance benefits in 1985, the regulation of individual dismissals, collective dismissals and fixed-term contracts in 1989 (Bover et al., 2000). According to Paulino (2000: 5):

From their inception in 1975 until 1984 unemployment benefits in Portugal were unrelated to past earnings and were fixed in terms of the minimum wage (introduced in May 1974). From 1985, however, benefits have been partly earnings related.

Since 1989, the unemployment insurance system in Portugal is more favourable for those who have only a short period of service (between eighteen months and three years). The age of the unemployed worker has increased (Bover et al., 2000). Table 2 presents the eligibility conditions, the maximum duration and replacement ratios of the unemployment insurance and assistance benefits, in Portugal, in the years of 1985 and 1989. Beneficiaries must have been contributing for at least eighteen months in the past two years in order to benefit. The maximum duration of the insurance benefits depends on the age of the unemployed worker. However, Nickell (1997) considers that the unemployment could be increased as a result of generous unlimited benefits, free of obligations and without sufficient assurance of finding new employment.

Table 2 - Unemployment insurance and assistance benefits, 1985-1989

|

| 1985 | 1989 |

| Eligibility of individual to insurance benefit | Employed for all last 3 years | Employed for 18 months of last 2 years |

| Eligibility to assistance benefits | All unemployed whose households have per capita income below 70% of minimum wage and do not qualify for unemployment benefits because exhausted their regular benefits or were not employed enough in previous year | All unemployed whose households have per capita income below 80% of minimum wage and do not qualify for unemployment benefits because those already exhausted or employed for insufficient time in previous 2 years |

| Maximum length of insurance benefit | 12 months plus one additional month for each year of tenure | In terms of age: age < 25 = 10 months, rising to 55 < age = 30months |

| Maximum benefit of assistance benefits | 15 months for those aged under 50 years 18 months for those [50 and 55[ years; 24 months for those over 55 years | As for unemployment benefits, unless these have already been exhausted; then half of that entitlement. For those over 55, assistance benefits are paid until age 60 |

| Replacement ratio of assistance benefits | 70% minimum wage if no dependents, rising to 100% minimum wage if have 6 or more dependents | 70% minimum wage with no dependents, rising to 100% if have at least 4 dependents |

Source: Bover et al. (2000: 423-424).

Perhaps the most striking element of the new law is the attempt to promote adaptability and flexibility in employment relationships. Consequently, the labour law reforms concerning the new employment benefit oblige workers to fulfil several requirements in order to qualify as beneficiaries. One of the formal requirements is to actively search for work. The aim is socio-professional insertion in the job market by their own initiative and proof thereof at the Employment Centre. This may eventually provide new possibilities for jobs for unemployed individuals. This seems preferable to a situation where the unemployed stay at home expecting some firm to call. It engenders a sense of individual responsibility of the unemployed and ensures that the money spent during the unemployment period is well administered.

The other formal requirement for eligibility as a beneficiary is the obligation to present oneself every two weeks, spontaneously or in response to a call from the Employment Centre, Social Security Institution or other entity competent by protocol. All these changes, were brought about by means of successive legislative measures which increased the number of special rules, making it difficult for the unemployed to abuse the system by for example, working while still receiving the unemployment financial support.

All these requirements aim to contribute to the personal betterment of unemployed individuals, their families and society in general by attempting to ensure that they are employed. Legislation describes social behaviour as being voluntary. Nevertheless it provides for certain compulsory action in order for individuals to qualify for unemployment benefits. These requirements are therefore satisfied as a result of an obligation imposed by the law rather than as a response to managers needs.

From an empirical perspective, changes in aggregate unemployment rates until the early 1990s largely reflect changes in relative employment rates in industry (Rogerson, 2004). Effectively, Table 3 reflects the employment and unemployment by economic sector, in Portugal, in the period 2002-2007, and the change from an agriculture-based economy into a service-based economy. The agriculture-based economy decreased from 12.5% in 2002 to 11.5% in 2007, while the service-based economy increased from 53.5% in 2002 to 58% in 2007.

Table 3 – Employment and Unemployment by economic sector, 2002-2007

|

| Years | |||||||

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |||

| Employment (%) | Agriculture | 12.5 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 11.5 | |

| Industry | 34.0 | 31.9 | 31.1 | 30.5 | 30.8 | 30.5 | ||

| Services | 53.5 | 55.4 | 56.9 | 57.7 | 57.7 | 58.0 | ||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Unemployment (%) | Agriculture | 7.2 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 5.3 | |

| Industry | 34.5 | 34.4 | 33.2 | 33.6 | 32.7 | 28.4 | ||

| Services | 58.3 | 59.0 | 61.2 | 60.4 | 61.7 | 66.3 | ||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Source: MTSS (2003b; 2004b; 2005b; 2006b; 2007b; 2008).

The unequal distribution of employment between men and women is a key feature of unemployment (Peters, 1995). Before the 1990s the unemployment rate in Portugal demonstrated that the number of unemployed women was much greater than the number of unemployed men. After the 1990s there was very little difference between the rate of unemployment of women and that of men.(Bover et al., 2000). The reduction of unemployment disparities on the basis of gender in the 1990s is important because these disparities threaten the attainment of nominal convergence, social cohesion and imply considerable variations in economic welfare (Sapsford & Bradley, 1999). Table 4 represents active population and unemployment by gender in December 2007.

Table 4 – Active Population and Unemployments by gender, December of 2007

|

| Active Population | Active Population with higher education | Unemployments | Unemployments with higher education | ||||

| Nº (103) | % | Nº (103) | % | Nº (103) | % | Nº (103) | % | |

| Men | 2,986 | 53.1 | 371,9 | 40.4 | 151,2 | 40.1 | 11,3 | 29.1 |

| Women | 2,641 | 46.9 | 548,0 | 59.6 | 226,3 | 59.9 | 27,5 | 70.9 |

| Total | 5,627 | 100.0 | 919,9 | 100.0 | 377,5 | 100.0 | 38,8 | 100.0 |

Source: GPEARI (2008) and MTSS (2008).

In the last decade, is possible to verify the increasing number of women in the labour market. This has been accredited to an improvement in the schooling and the experience profile of employed women. This improvement was more pronounced than that of employed men (Cardoso, 1999).

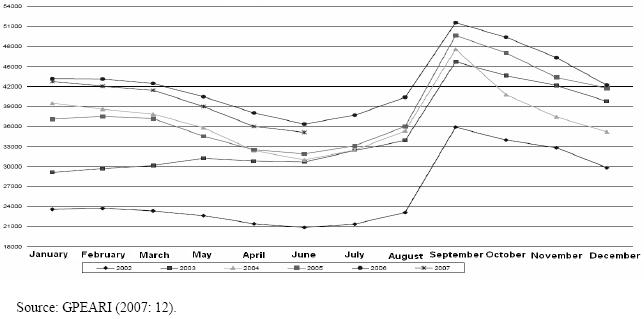

However, irrespective of workforce characteristics, the authors put forward the proposition that Portugal must adopt measures to improve the qualifications and training of the workforce because the unemployment rate in Portugal is mainly a result of either a complete lack of or alternatively, inadequate education and vocational training (Moniz & Woll, 2007). Figure 1 show unemployment and higher education, in Portugal, in the period 2002-2007, and reinforce the last comments.

Figure 1 – Unemployments with higher education, 2002-2007

Table 5 shows employment income in specific sectors in Portugal during the period 2002-2005. In all the years analysed, it is possible to conclude that the average income in the textile industry was 494.00, in the construction industry it was 606.00, in the health and social service industry it was 630.00, in the food industry it was 656.00, and in the trade industry it was 700.00. These incomes are all lower than the average income in Portugal which is 728.00. However, there has been an increase in income in these specific sectors, aside from in the fields of informatics activities & communication technology and in public administration in 2005. Some studies have concluded that the higher level of income has proved to be barrier to success. For a long time and especially between 2002-2005 managers were strongly averse to the constant increase of labour costs that affected the net result of firms and the state budget of public institutions.

Table 5 - Employment Income, 2002-2005

| Economic Sector | Years | |||

| (Euro) | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

| Food industry | 620.10 | 649.61 | 669.68 | 684.29 |

| Textile industry | 467.94 | 487.98 | 503.64 | 516.37 |

| Construction | 560.96 | 590.81 | 622.09 | 648.91 |

| Trade | 659.01 | 691.20 | 715.84 | 733.86 |

| Informatics Activities & Communication Technology | 1,448.90 | 1,512.40 | 1,515.05 | 1,478.63 |

| Postal services | 1,145.72 | 1,210.14 | 1,274.72 | 1,314.89 |

| Public administration; Services for citizens |

|

|

|

|

| Public administration | 1,055.95 | 1,137.61 | 1,152.07 | 881.45 |

| Education | 805.61 | 884.79 | 940.14 | 966.77 |

| Health; Social service | 581.21 | 605.32 | 640.07 | 693.03 |

| Other services | 810.95 | 811.30 | 807.95 | 848.24 |

| Average income Portugal | 687.48 | 714.29 | 741.41 | 767.35 |

Source: MTSS (2003a; 2004a; 2005a; 2006a).

The unemployment rate has doubled in the same period, reaching 8% in 2007, with a growing share of long-term unemployment, as a result of the inability of the labour market to get job-seekers back into work as effectively as in the past (OECD, 2008). In comparison with other OECD countries, the employment protection legislation of Portugal is restrictive (Blanchard & Portugal, 2001). Thus, according OECD (2008: 9):

to facilitate the adjustment of the economy to the forces of globalisation and reduce the social costs of the adjustment process, policies have to focus on easing labour market regulations that hinder workers mobility, while reinforcing the support to job losers. Several reforms have been made over the past few years, including changes to the labour code, stronger controls of undeclared work, bringing the social security schemes of the private and public sectors closer and tighter eligibility conditions for unemployment benefits.

Another solution was proposed by Cavalcanti (2004), who presents a model in which employment protection increases with job tenure. Also, he argues that the increase in employment protection may subsequently result in more dismissals as firms attempt to compensate for the continuously increasing costs. This model may raise a problem because in the context of social responsibility, solutions must be economically sustainable and it seems that, in the Portuguese reality, this is not possible.

This approach constitutes an important step in the strengthening of work incentives and facilitation of workers mobility, as well the improvement and adaptability of the labour market. This is the new framework for active labour market policies that is under discussion. This framework, when approved, can implement the evaluation and rationalisation of activation programmes, emphasising the improvement of the performance of public employment services (OECD, 2008). The authors suspect that the most salient aspects involving active labour policies cannot be achieved solely by laws, codes or regulations, because individuals can more easily force firms to make job offers.

In Portugal, the main instrument for labour market policy is the National Action Plan for Employment that was adopted by the Ministers Council Resolution nº 59/98 of 5 May 2008. It expresses the commitment of the Portuguese State, within the scope of the Lisbon Strategy, to implement the guidelines on employment (MTSS, 2007c), in coordination with the four pillars which sustain the European employment strategy, specifically: to improve employability, to foster entrepreneurship, to encourage the adaptability of workers and firms, and to strengthen policies on equal opportunities (Moniz & Woll, 2007, Moniz, 2008).

Moniz & Woll (2007: 9) synthesizes as the basic principles of Portuguese labour policy:

· Modernisation of education system;

· Development of professional vocational training in co-operation with the economy;

· Reorientation and intensification of vocational training and retraining;

· Development of exemplary measures for labour market integration/development of active instruments and measures for labour market integration of deprived social groups;

· Promotion of business start-ups (in particular SME);

· Employment incentives/employment creation in new fields of employment.

These principles satisfy the four objectives of the labour market policy, particularly: promotion of an adequate transition of the youngsters to active life; promotion of social and the fight against long term unemployment; improvement of basic and professional qualifications of the working population in a perspective of lifelong training; preventive management measures and follow-up of sectoral restructuring processes (MTSS, 2007c). These strategies to secure decent employment conditions and at the same time reduce unemployment operate in the context of territorial and sectoral differentiation phenomena, as well the profound political, social and economic transformations.

The most significant development in the Portuguese labour code, during the year 2008, was the introduction of major changes. The main goals of the reform are the following: increase the adaptability of firms, promote collective contractual regulation, reform the legal system governing redundancies, strengthen the effectiveness of labour law, combat segmentation and precariousness, promote the quality of employment, and adapt and articulate labour law, social protection and employment policies.

Previously, in April of 2006, the first phase of the public debate focused on the analysis of labour relations in Portugal. The final results were published in the Green Paper on labour relations. In December of 2007, the second phase of the public debate focused on improving the analysis and defining recommendations. The final results were published in the White Paper on labour relations. And, in April 2008, the third and last phase of the debate focused on the reform of labour relations in Portugal, prior to the submission of the new Labour Code to the Portuguese Parliament. As Lima (2008) explains:

on 5 June 2008, around 200,000 persons participated in a demonstration organised by the trade union confederation CGTP against the ongoing labour reforms in the private and in public sector and, in particular, against the government proposals on the revision of the labour code. This is the third time that the present socialist government has faced a major demonstration organised by trade unions.

For those reasons, the promotion of an adequate transition for youngsters to an active working life should be centred in a labour market that fosters equality and improves the quality of skills training and intensifies the participation in programs that guarantee professional performance in order to serve the employability, active citizenship, as well the social inclusion of all. Furthermore, the battle against long term unemployment must be integrated into an educated and knowledgeable society that possesses not only qualifications but also competencies. In other words, education, especially that of a higher level, must carry out a strategic function (David & Abreu, 2007). Thus, the improvement of basic and professional qualifications of the working population, in a perspective of lifelong training, is a way to prevent unemployment. It requires an improvement of academic and professional qualifications and the level of specialization, as well as a broadening of the qualifications and knowledge base of the Portuguese population in an international context (MCIES, 2006), with view to assure an economic, social and technological modernization of the labour market in Portugal.

CHALLENGES FACING THE PORTUGUESE LABOUR MARKET

The Portuguese government has adopted a proactive approach regarding its employment policy. Also, it is associated with greater demands from individuals seeking more efficient and adequate measures to improve resource mobilization and to target the most critical and problematic challenges, such as qualifications, education, and the social protection of the Portuguese population. These challenges are the most influenced by European Union directives and the ways in which the transposition of the Directives has been intertwined with the national legal system.

The first challenge is the qualification of the Portuguese population. Since March of 2007, the agreement for the reform of vocational training has been promoted by the Portuguese government and its social partners. This agreement introduces new tools and redesigns the institutional framework based on several strategic objectives as well as practical measures:

- generalise the secondary level of education and promote the development of occupational courses at a secondary school level;

guarantee the certification of all occupational courses, in educational as well as in professional terms;

offer a vocational training syllabus to meet companies modernisation requirements as well as upgrade workers education and skills;

reinforce the role of the system of recognition, validation and certification of competences;

combat the informal economy as well as managerial practices which undermine the chances of workers gaining qualification;

render effective the individual right to annual minimum hours of vocational training;

upgrade management skills, providing training adapted to their particular needs;

promote training on social dialogue, in order to strengthen collective bargaining (MTSS, 2007a).

In this agreement, the main difference between employers and unions was centred on the right of access to vocational and educational training (VET) that is included in the Labour Code. The law stipulates that all workers are entitled to an annual minimum of 35 hours of certified VET and since 2006 to 55 hours. Furthermore, it defines the implementation of the training clause for young workers, aged 16 to 18 years who did not complete compulsory education and who do not have professional skills.

Carneiro et al. (2007) reveals that the skill levels in Portugal have been developing at a relatively slow pace, since the end of the 1980s, mainly due to: the resistance caused by a production and entrepreneurial structure based on low skills; a slow generational renewal of the labour market; an early dropout from the education system; and very low investment in education, including adult education and vocational training.

For all these reasons, the skills of each worker are vital. Recently, in 2007, the Commission staff working document Schools for the 21st Century stated:

Almost a third of the European labour force is low skilled, but, according to some estimates, by 2010 50% of newly created jobs will require highly skilled workers and only 15 % will be for people with basic schooling (EC, 2007: 4).

These competencies refer to the knowledge, skills and attitudes that serve personal fulfilment, social inclusion and active citizenship, as well employability. Effectively, dynamic technological progress requires high and constantly updated skills, while growing internationalisation and new ways of organising companies, call for social, communicative, entrepreneurial and cultural competencies that help people to adapt to changing environments and contribute to sustainable development (EC, 2007).

Previously, in 2006, the Progress Towards the Lisbon Objectives in Education and Training specified that all individuals need a core set of competenciies for employment, social inclusion, lifelong learning and personal fulfilment (EC, 2006). These competencies should be developed through the integration of a social dimension in the policies of education, technology and labour, i.e., the dimension related to labour process, work organisation, learning and qualification processes and job content when the technological development policy is designed (Moniz, 2006).

In Portugal, as well in any other country, the diffusion of technologies, education and lifelong learning are the main determinants of growth in the long term, as opposed to functioning labour and product markers that are indirectly relevant to economic growth (Aiginger, 2005). In order to achieve this growth and the development of a qualification process and job content, the higher education system has a particular role to play.

The second challenge is the education of the Portuguese population. The main aspects of the higher education system are the diversification of the sub-system (polytechnic versus university), the dispersion of the system to all geographical locations (all over Portugal, Madeira and Açores Autonomous Region), and the change of legal status (private versus public). For example, the polytechnic institutions have, as their main objectives, regional development and a close interaction with their operational environment that provides a flexible reaction to changes in environment (Kettunen & Kantola, 2006). Polytechnic teaching presents some advantages, such as: an innovative and dynamic capacity compared to traditional structures; flexibility and ability to adapt to the socio-economic context (Abreu et al, 2003); a close connection with the productive and social entities of the area where it is located; and a strategy of diversification of the existing study programmes (David & Abreu, 2007).

The diversification of the higher education system would increase the qualification base of the Portuguese people. As Caseiro et al. (1996: 437) points out:

( ) a lack of qualifications in some sectors has already been observed ( ) and all elements indicate a growing need of engineers, scientists and technicians in the future, and the fear is that educational systems and vocational training systems are not prepared to meet the required number and the range of final year degree students.

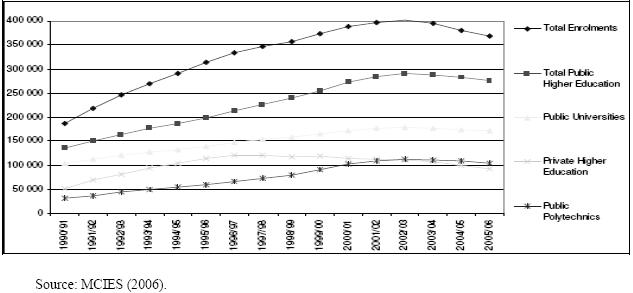

Figure 2 presents the evolution of students in the Portuguese higher education system between the years 1990 and 2006. It is possible to conclude that the higher education system has rapidly grown from 30.000 students in the sixties, to nearly 400.000 students by the end of the 20th century. This is a result of the system having being opened to young people of all social classes since the early 70s. The new degrees and diversification of the field of study allow the higher education system in the national context to strengthen its capacity and level of specialization, as well as to help broaden the qualification knowledge base of the Portuguese population in an international context (MCIES, 2006) (see Figure 1).

Figure 2 - Evolution of students in the Portuguese higher education, 1990-2006

However, the higher education system needs to be re-organised and rationalised, because technological progress requires a high level of skills and constantly updated of skills. In the past, the growth of higher education occurred essentially in the scientific areas of classic studies, social sciences (namely economics and management), and legal studies, which were supported by private education (Correia et al., 2002). In the present and the future, the growth of higher education system depends on the fields of engineering, science and technology training, so that the higher education programmes can meet the demands of the labour market. The students of a superior higher education system should develop their capabilities in order to reap the benefits of high standards of living, a healthy environment, a low cost of living, guaranteed sustainable development of the country and the maintenance of social support schemes (Abreu et al., 2003; 2007).

The social support of students is one consequence of the equality of access to opportunities to higher education in terms of the United Nations Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (UN, 1976). For example, the support system accorded to the students in higher education in Portugal aims to mitigate the economic difficulties of those from disadvantaged social backgrounds. This is particularly important since the last decade was characterised by an increase in cost-sharing by raising the level of tuition fees in public institutions and by expanding full-cost fee private institutions (MCIES, 2006).

Previously, the White Paper on Growth, competitiveness and employment, issued by the European Commission in December 1993, encourages the lowering of labour costs and the increase in labour market flexibility with view combating unemployment. The objectives is to make it easier for young people to enter the labour market and to promote the re-employment of the long-term unemployed (EC, 1993). The authors agree with Meschi (1995), who argues that if weekly hours of work were more flexible, more people could be employed, especially in those in low income countries such as Portugal, because the income per-capita would rise and the speed of convergence would increase.

The third challenge is the social protection of the Portuguese population. The main challenge in this regard is the modernisation of the system itself and the achievement of present and future financial sustainability.

The first aspect is related to the financial generosity of the unemployment benefit system, as well as the potentially long duration of its payments which may be major contributing factors to the maintenance of a considerable level of long-term un employment in Portugal. Table 6 presents the unemployment rate by regions and the long-term rate, on the period of 1998-2006.

Table 6 – Unemployment, 1998-2006

|

| 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | |||||||||

| Norte | 5.0 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 8.8 | 8.9 |

| Centro | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 5.5 |

| Lisboa | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 8.5 |

| Alentejo | 7.9 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Algarve | 6.0 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.5 |

| Açores | 4.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| Madeira | 3.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 5.4 |

| Long-term unemployment (%) | |||||||||

| Portugal | 45.4 | 41.2 | 43.8 | 40.0 | 37.3 | 37.7 | 46.2 | 49.9 | 51.7 |

Source: BP (2006: 177)

A global analysis of Table 6, from 1998 to 2006, allows the conclusion that the labour market in Portugal was characterised by a high increase in the unemployment rate, particularly in the Alentejo, North of Portugal, Lisboa, Center of Portugal and Açores, and, a decrease in Algarve and Açores. However, unemployment rates remain high and therefore greater permanence of workers in labour market must be promoted. This would contribute to the financial stability of the social system.

Furthermore, table 6 shows the variable long-term unemployment, which considers all persons unemployed for 12 months or more. Since 1998 this variable has been increasing and, in 2006, it reached 51.7% of total of unemployed. This value could even worsen as Banco de Portugal (2006: 73) points out, because it excludes very long-term unemployment, i.e., with duration of 25 months and more, and it continues to grow at a rate of over 20%, representing around 30% of the unemployed in 2006. The authors believe that this has happened because of the benefits of a minimum guaranteed income.

One of the last countries in the European Union to introduce a guaranteed minimum income (GMI) programme was Portugal. The Portuguese Parliament approved the Law 19-A/96 of June 29 1996 although it only came into full force on July 1997, after a trial period of few months in a limited area of the country. Table 7 shows the beneficiaries of the minimum guaranteed income. It is important to specify that the minimum guaranteed income is not just an unemployment benefit. It is part of a social assistance programme which is intended to help its beneficiaries and their households in vocational and rehabilitation training, employment, health, education, housing and justice areas.

Table 7 – Beneficiaries of the minimum guaranteed income, 1998-2000

|

| Unit | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 |

| Total | number | 318.278 | 417.153 | 412.489 |

| 19-64 years | number | 178.373 | 237.320 | 239.608 |

Source: BP (2000: 163)

By integrating social responsibilities, a rather original provision is made whereby the employer's social security contributions (taxa social única or single social tax) increase in accordance with the number of workers recruited on fixed-term contracts and in accordance with the duration of their respective contracts. This happens because the citizens need more protection, the State must promote sustainable employment and firms do not typically exhibit consistent moral behaviours. Therefore, the government must, by means of labour legislation oblige firms to contribute by making more payments.

In fact, if firms and individuals were to adopt more socially responsible behaviour, they could avoid additional regulations imposed by the government and they could gain more freedom to voluntarily partake in socially responsible activities which are economically sustainable. These contributions reduce the profitability of firms and oblige managers to take economic and financial decisions that are more appropriate to the firms.

CONCLUSION

In order to explore the perspectives of socially responsible behaviour in the labour market and to fully understand the determinants of their SRB and whether or not their orientation, the authors show several perspectives that must be discuss.

The first perspective is critically examined in this research and it is related with several people, who do not want to work or only want to work as few as possible. This is result of the role of basic skills of literacy and numeracy has become ubiquitous. So, firms and Institutions have witnesses a shift in labour demand towards more skilled workers. In such environment, firms face a hard labour problem on meeting their new demands. Also, the facts and statistics justify this argument and it is urgent the need of proactive attitude recommended for private and public sector to stimulate persons to work and develop its skills. For example, Geishecker & Gorg (2008) provide evidence of a negative (positive) effect of interaction outsourcing on the real wage of low-skilled (high-skilled) workers in Germany.

The second perspective is based on the Convention signed in Paris on December 1960, witch allows the OECD to promote policies to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of social responsibility with view to sustainability development of the economy world (OECD, 2004). Effectively, the genesis of labour market policies was essentially pragmatic, i.e., an unplanned response to the clearly perceived social problem of high unemployment rates (Jackman et al., 1990).

The third perspective is materialized in the work promoted by the Portuguese governments relatively to guaranty the relationship between employment, industrial relations and higher education institutions that play a socially responsible role in the society, at a national level or European and international level, in substitution of concerns exclusively economic.

According to these perspectives, Portugal must engage socially responsible behaviours in different organizational contexts, as in the labour market. But, only the time will prove it...

References

Abreu, R., David, F., Martins, N. & Rei, C. (2007). Accounting for Higher Education Institutions: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility. Paper presented to 30th Annual Congress of EAA, Lisboa (Portugal), 1-22.

Abreu, R.M., David, M.F., Silveira, M.C. & Marques, P. (2003). Contributo para a Avaliação, Revisão e Consolidação da Legislação do Ensino Superior. In Amaral, A. (ed). Avaliação, Revisão e Consolidação da Legislação do Ensino Superior. Matosinhos: Cipes, 46-50.

Aiginger, K. (2005). Labour market reforms and economic growth - the European experience in the 1990s. Journal of Economic Studies, 32 (5/6), 540-573.

Assembleia da República (AR, 2005). Lei Constitucional nº 1/2005 - Sétima revisão constitucional. Diário da República, 155, I Série-A, August 12.

Banco de Portugal (BP, 2000). Annual Report. Report and Financial Statements. Lisboa: BP.

Banco de Portugal (BP, 2002). Annual Report. Report and Financial Statements. Lisboa: BP.

Banco de Portugal (BP, 2006). Annual Report. Report and Financial Statements. Lisboa: BP.

Blanchard, O. & Portugal, P. (2001). What Hides Behind an Unemployment Rate: Comparing Portuguese and U.S. Labor Markets. American Economic Review, 91 (1), 187-207.

Bover, O., García-Perea, P. & Portugal, P. (2000). Labour market outliers: Lessons from Portugal and Spain. Economic Policy, 15 (31), 381-428.

Cardoso, A.R. (1999). Firms' Wage Policies and the Rise in Labor Market Inequality: The Case of Portugal. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 53 (1), 87-102.

Carneiro, R., Valente, A., Fazendeiro, A., de Carvalho, L. & Abecasis, M. (2007). Baixas qualificações em Portugal. Cogitum, 29. Lisboa: Study Centre for Peoples and Cultures of Portuguese Expression, Ministry of Labour and Social Solidarity.

Caseiro, T.A., Conceição, P., Durão, D.F.G. & Heitor, M.V. (1996). The Development of Higher Engineering Education in Portugal and the Monitoring of Admissions: A Case Study. European Journal of Engineering Education, 21 (4), 435-445.

Cavalcanti, T. (2004). Layoff costs, ternure and the labor market. Economics Letters, 83 (3), 383-390. [ Links ]

Correia, F., Amaral, A. & Magalhães, A. (2002). Public and Private Higher Education in Portugal: unintended effects of deregulation. European Journal of Education, 37 (4), 457-472.

Crowther, D. & Rayman-Bacchus, L. (2004). The Future of Corporate Social Responsibility, in Crowther, D. and Rayman-Bacchus, L. (eds.). Perspectives on Corporate Social Responsibility. Aldershot: Ashgate, 229-249.

David, F. & Abreu, R. (2007). The Bologna Process: Implementation and Developments in Portugal. Social Responsibility Journal, 3 (2), 59-67.

David, F. & Abreu, R. (2008). Taxation and Fiscal Evasion: A perspective on Corporate Social Responsibility. In Crowther, D. & Capaldi, N. (eds). The Ashgate research companion to corporate social responsbility. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 357-385.

European Commission (EC, 1993). White paper – Growth, competitiveness and employment: the challenges and ways forward into the 21st century, COM (93) 700. Brussels: Official publications of the European Commission, December 5.

European Commission (EC, 2001a). Green paper – Promoting a European framework for Corporate Social Responsibility, COM (2001) 366 final. Brussels: Official publications of the European Commission, July 18.

European Commission (EC, 2001b). Making a European Area of Lifelong Learning a Reality, COM (2001) 678 final. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Communities.

European Commission (EC, 2002). Corporate Social Responsibility: A business contribution to Sustainable Development, COM (2002) 347 final. Brussels: Official publications of the European Commission, July 2.

European Commission (EC, 2006). Commission Staff Working Document: Progress Towards the Lisbon Objectives in Education and Training - Report based on indicators and benchmarks, SEC(2006) 639. Brussels: Official publications of the European Commission, May 16.

European Commission (EC, 2007). Commission Staff Working Document: Schools for the 21st Century, SEC(2007) 1009. Brussels: Official publications of the European Commission, July 11.

Fernandes, A. (2002). Conciliation, mediation and arbitration. National report - Portugal. Brussels: Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs.

Gabinete de Planeamento, Estratégia, Avaliação e Relações Internacionais (GPEARI, 2007). A Procura de Emprego dos Diplomados Desempregados com Habilitação Superior – Junho de 2007. Lisboa: GPEARI.

Gabinete de Planeamento, Estratégia, Avaliação e Relações Internacionais (GPEARI, 2008). A Procura de Emprego dos Diplomados Desempregados com Habilitação Superior – Dezembro de 2007. Lisboa: GPEARI.

Geishecker, I. & Gorg, H. (2008). Winners and losers: A micro-level analysis of international outsourcing and wages. Canadian Journal of Economics, 41 (1), 243-270.

International Labour Organization (ILO, 2003). The ILO: What it is. What it Does. Geneve: ILO.

Jackman, R., Pissarides, C. & Savouri, S. (1990). Labour market policies and unemployment in the OECD. Economic Policy, 5 (2), 449-490.

Kettunen, J. & Kantola, M. (2006). The implementation of the Bologna Process. Tertiary Education and Management, 12 (3), 257-267.

Lima, M. & Naumann, R. (2005). 2004 Annual Review of Portugal. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Lima, M. (2008). Massive demonstration against proposed labour reforms. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Meschi, M. (1995). European labour markets: regulations and integration. European Business Journal, 7 (4), 41-46.

Ministério da Ciência, Inovação e Ensino Superior (MCIES, 2006). Tertiary Education in Portugal. Working Document - MCIES.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2003a). Quadros de Pessoal 2002. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral de Estudos, Estatística e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2003b). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Novembro e Dezembro de 2002. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2004a). Quadros de Pessoal 2003. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral de Estudos, Estatística e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2004b). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Dezembro de 2003. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2005a). Quadros de Pessoal 2004. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral de Estudos, Estatística e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2005b). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Fevereiro de 2005. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento/MTSS.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2006a). Quadros de Pessoal 2005. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2006b). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Dezembro de 2005 e Janeiro de 2006. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2007a). Acordo para a reforma da formação Professional - Março de 2007. Lisboa: MTSS.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2007b). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Abril de 2007. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2007c). National Action Plan for Employment (2005-2008). Follow-up Report 2006. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Ministério do Trabalho e da Solidariedade Social (MTSS, 2008). Boletim Estatístico: Emprego, Formação, Trabalho - Maio de 2008. Lisboa: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Moniz, A. (2008). Labour Market Policy in Portugal. Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper, 6588, 1-17.

Moniz, A.B. & Woll, T. (2007). Main features of the labour policy in Portugal. IET Working Papers Series, 2, 1-13.

Moniz, A.B. (2006). Foresight methodologies to understand changes in the labour process: Experience from Portugal. Enterprise and Work Innovation Studies, 2, 105-116.

Nickell, S. (1997). Unemployment and Labor Market Rigidities: Europe versus North America. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11 (3), 55-74.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2000). The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises-Revision. Paris: OECD Publications.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2004). OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Paris: OECD Publications.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2008). Economic Survey of Portugal 2008. Policy Brief, June.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2001). Corporate Social Responsibility: Partners for Progress. Paris: OECD Publications.

Paulino, T. (2000). Labour market transition in Portugal, Spain, and Poland. Paper presented to Phare Workshops on Labour Market Flexibility in the Wake of EU Accession, Coimbra (Portugal), 1-28.

Peters, T. (1995). European Monetary Union and labour markets: What to expect? International Labour Review, 134 (3), 315-332.

Rodrigues-Piñero, M. (2005). Developments in Labour Law in Portugal between 1992 and 2002. Portuguese National Report. Brussels: Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs

Rogerson, R. (2004). Two Views on the Deterioration of European Labor Market Outcomes. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2 (2/3), 447-455.

Sapsford, D. & Bradley, S. (1999). The European economy: Labour market efficiency, privatisation and minimum wages. Industrial Relations Journal, 30 (4), 291-312.

United Nations (UN, 1976). International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Genebre: UN.

United Nations (UN, 2008). United Nation Global Compact [online]. Available at: http://www.unglobalcompact.org/AboutTheGC/.

Nota Curricular

*Rute Abreu [1], professor in the Business & Economics Department at the Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão of Instituto Politécnico da Guarda (Portugal). She is the scientific coordinator of accounting and finance and she earned his PhD from the Universidad de Salamanca (Spain) in 2009. Her research and teaching interests include corporate social responsibility, corporate finance, investment appraisal, firm valuation, accounting, and physics. Both in national and international level, she has published many articles, presented papers on conferences, seminars, courses and develop the consultant activity of organizations, firms, and opinion makers.

*Fátima David [1], professor in the Business & Economics Department at Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão of Instituto Politécnico da Guarda (Portugal). She earned his PhD from the Universidad de Salamanca (Spain) in 2007. Her research and teaching interests include corporate social responsibility, corporate finance, taxation, and accounting. She has published abundant national and international research papers, presented papers on numerous national and international conferences, and develop the consultant activity of organizations, firms, and opinion makers.

[1] Escola Superior de Tecnologia e Gestão of Instituto Politécnico da Guarda

Av. Dr. Francisco Sá Carneiro, 50, 6300-559 Guarda, Portugal

(recebido em 8 de Abril de 2010; aceite em 30 de Junho de 2010)