Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Motricidade

versão impressa ISSN 1646-107X

Motri. vol.9 no.4 Vila Real dez. 2013

https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.9(4).96

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Relationship between sport commitment and sport consumer behavior

Relações entre o compromisso desportivo e o comportamento de consumo de desporto

N.E. FernandesI, A.H. CorreiaI, A.M. AbreuII, R. BiscaiaIII

IFaculdade de Motricidade Humana - Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal.

IICentro de Competências de Ciências Exatas e Engenharias, Universidade da Madeira, Portugal.

IIICentro Interdisciplinar de Estudo da Performance Humana (CIPER), Faculdade de Motricidade Humana da Universidade de Lisboa; Escola de Turismo, Desporto e Hotelaria, Universidade Europeia, Portugal.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between sport commitment and three types of sport consumer behaviors: participation frequency, sporting goods and media consumption. A survey was conducted among sport participants of both individual and team sports, fitness and outdoor activities (n= 900). The survey included questions related to demographic information, measures of sport commitment and sport consumption behavior. The results analyzed trough structural equation modeling showed that the sport commitment influences positively the participation frequency, sporting goods consumption and media consumption. Implications of these results are discussed and suggestions for future research on sport consumers are provided.

Keywords: sport, consumer behavior, commitment

RESUMO

O objetivo deste estudo foi examinar a relação entre o compromisso desportivo e três tipos de comportamentos de consumo de desporto: frequência de participação, consumo de artigos desportivos e consumo de media. Foi aplicado um questionário a praticantes de desportos individuais e de coletivos, de fitness e de atividades outdoor (n= 900). O questionário incluiu questões relacionadas com informações demográficas, com o compromisso desportivo e com o comportamento de consumo de desporto. Os resultados obtidos a partir de um modelo de equações estruturais forneceram evidências de que o compromisso desportivo tem uma influência positiva sobre a frequência de participação, sobre o consumo de artigos desportivos e de media. As implicações destes resultados são discutidas e sugestões para futuras pesquisas sobre consumidores de desporto são fornecidas.

Palavras-chave: desporto, comportamento de consumo, compromisso

Sports have a strong psychological, social and economic impact on the lives of a lot of people. Previous research frequently refers that millions of people are involved in sport, either as participants or as spectators. For example, Funk (2008) noted that 75% of the adults in England are involved in some sort of physical activity, while 72% of the Americans recently attended a sporting event. Because the sports industry is one of the largest industries in the United States, estimated at $441.1 billion (Plunkett, 2008), the application of findings in this area of research continues to be important for a number of industries and organizations (Casper, 2007). A growing body of literature about consumer behavior is focused on the motives for attending sporting events (e.g., Neale & Funk, 2006) or participating in specific sport activities (e.g., Funk, Mahony, & Havitz, 2003). However, it is necessary to simultaneously investigate other means of sport consumption (Trail, Robinson, & Kim, 2008), such as the consumption of sporting goods and sports media, which will strengthen the sporting organization, in particular, and the sports market place in general (Stewart, Aaron, Smith, & Nicholson, 2003).

The commitment with a sport organization is often suggested as being the factor that induces consumption behaviors (Weiss & Weiss, 2006). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between sport commitment and sport consumer behaviors, such as participation frequency, sporting goods and media consumption. It is expected that the analysis of these relationships may help sport managers to design effective retention strategies and promote different forms of sports consumption. The concept of sport commitment derives from the social exchange theory proposed by Thibaut and Kelley (1959), and according to the authors, people participate in the activities as long as the result of their participation is sufficiently favorable. Favoritism is determined by the balance between benefits and costs. Scanlan, Carpenter, Schmidt, Simons, and Keeler (1993) designed a framework to the sport settings that is based on the psychological processes related to sports participation, which defines sport commitment as a psychological state representing the desire to continue to participate in a particular sports program or sport in general. The concept of commitment is pivotal in consumer behavior because theorists have suggested that it represents resistance to change. This means that, even against persuasive attempts (e.g., an alternative activity/product) they are still loyal to it (Casper & Stellino, 2008). Thus, increasing the participants commitment is an important issue for sport managers (Casper & Stellino, 2007). Casper (2007), and Casper and Stellino (2007) noted that commitment was related with purchase intentions and participation frequency. It seems logical that a committed participant will spend more money in equipment and will play more often. However, it is necessary a further understanding of the relationship between the psychological state of commitment and the consumer behavior (Casper & Stellino, 2008). In addition, up to date, the sport commitment studies have never used diversified samples contemplating sport (teams and individuals), fitness and outdoors activities. Also, the role of sport commitment has never been used to understand media consumption.

Previous literature refers to sport consumption behavior as a process that involves the individuals when they select, buy, use and have products and services related with sport to satisfy their needs (Funk, 2008). Consumer behavior related to sports practice represents a substantial economic impact in the sport industry (Casper, 2007). Fischer (2008) refers that sport participation has blossomed into a lucrative and highly influential industry. As a result, the sport marketing researchers have done a serious work to enhance the attractiveness of the sport organizations (Dwyer & Drayer, 2010). According to Pitts and Stotlan (2002), participants consumption behavior is defined as an action performed when searching for, participating in, and evaluating the sport activities that consumers believe will satisfy their needs. However, studying the consumer behavior is always complex, since sport consumers show a confused order of attitudes and behaviors (Meir, 2000; Redden & Steiner, 2000; Shank, 2004; Westerbeek & Smith, 2003). Some attend regularly the games while others attend only occasionally. There are also some consumers who spend most of their time in sport sites and exploring the internet while others watch paid sport channels. Some read sport magazines while others listen to sports on the radio. Some choose professional sports, while others choose amateur sports, fitness, or outdoors activities. The frequency in which they participate in sports is different as it is in the acquisition of sporting goods. To sum up, sport consumers experience sports in different ways. It is important to systematize the sport consumption behavior to a better understanding of the sport consumers and the differences between them (Stewart et al., 2003). In our study we will focus on three types of consumption: participation frequency, media consumption and sporting goods consumption.

Based on previous literature, we will develop these different types of sport consumption. Several researchers have focused on the participant frequency to understand the behavioral involvement of sport consumers (Casper, 2007). Beasley, Shank, and Ball (1998) indicated that the involvement level is directly related with the number of hours that people participate in sports. Specialists in marketing are interested in the involvement because it has been shown to be a reliable predictor of the sport behavior (e.g., Shank, 2004). Therefore, the concept of involvement becomes important to marketing, since one of the goals of this area is to increase the frequency in which participants choose to join a specific activity (Casper & Stellino, 2007). These authors suggest that the increase in the time of practice will increase the players commitment. Therefore, the first hypothesis was suggested:

H1: The sport commitment positively influences the participation frequency.

According to Pitts and Stotlan (2002), spectators are consumers who obtain benefits for attending the events. Sport spectators observe the sporting event in two broad ways: they attend the event or they experience it via one of several sports broadcast media. One of the interesting characteristics of sport consumption is that it can be experienced through the media such as television, radio and internet (Dwyer & Drayer, 2010). The sport marketers also work to increase the audience on a variety of broadcast media. This includes magazines, television options, premium cable and satellite networks (Dwyer & Drayer, 2010). According to Hau (2008), television rights for the National Football League and Major League Baseball are over $3.7 billion and 750 million anually. In addition, there has been an explosion in the number of websites that feature sport news and require a subscription fee in order to have access to the websites. Thus, with the creation of social networks such as facebook, twitter and blogs, sport fans are gaining the ability to actively interact with sport products at a level unknown a decade ago. According to Kim and Trail (2011), the development of media has changed the spectator-sport industry. Although we have not found a relationship between media and commitment in the literature, it is important to study this relationship for all the motives reported prior. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2: The sport commitment positively influences media consumption.

Sporting goods represent tangible products that are manufactured, distributed and marketed in the sports industry. Sport marketers sell their products based on the benefits these products offer to consumers (Pitts & Stotlan, 2002). Thus, it is necessary to understand which products are important to a specific market and develop a strategy that fills those needs (Casper & Stellino, 2007). The sporting goods that are considered in this study are sport shoes, sportswear and practice support material. Sport shoes were once primarily focused on the participant market, but this has changed significantly since the advent of Nike`s Air Jordan shoes (Fullerton, 2007). Sport shoes are an integral part of almost everyone's wardrobe. For participants, there are designs which are manufactured for specific activities. Sportswear is clothing that falls into one of two categories. First and foremost, it may be purchased to facilitate participation. The second category is based on the acknowledgment that sportswear can be fashionable within certain market segments. At last, the practice support material is considered a product that influences the quality of sport performance (Pitts & Stotlan, 2002). Casper and Stellino (2007) studied some of these products and found that highly committed tennis players are likely to spend more money on tennis equipment. Thus, we proposed and tested the following hypothesis:

H3: The sport commitment positively influences the consumption of sporting goods.

METHODS

Participants

The study sample is based on sport consumers from Madeira Island, Portugal, who accepted to participate voluntarily under the guarantee of anonymity of their responses.

The participants were told that their answers would be completely confidential and written reports would be based on a group data with no names revealed. After being aware of the study, the participants signed a written consent.

The sample was made up by 900 sport consumers: 300 of both team and individual sports; 300 participants of fitness activities and 300 of outdoor activities. The ages of respondents ranged from 19 to 44 years old, and the mean age was 30.10 years old (SD = 7.47). A total of 440 participants were female (48.8%) and 460 were male (51.2%). The weekly frequency of practice was 3.93 times (SD = 1.74), and the whole average time of sport practice of the respondents was 13.00 years (SD = 8.91).

Measures

The survey was composed of three parts. The first part included demographic information such as age, gender, and type of practice (team and individual sports, fitness and outdoors activities). In the second part, issues related to sport commitment were addressed. In the third part, issues concerning to the three types of sports consumption were added.

Sport commitment

The 4-item scale proposed by Scanlan et al. (1993) was used to assess commitment, and includes the following items: "I am dedicated to continue the practice of sport; I am determined to continue the practice of sport; I will do everything to not abandon sports; It is difficult for me to abandon sports". All items were measured through a 5-point Likert-type scale, anchored by totally disagree (1) and totally agree (5).

Consumer behavior

Three types of consumption behavior were assessed based on previous literature: media consumption (Dwyer & Drayer, 2010; Pitts & Stotlan, 2002), sporting goods (Casper, 2007; Casper & Stellino, 2007; Fullerton, 2007; Pitts & Stotlan, 2002), and participation frequency (Casper, 2007; Casper & Stellino, 2007). To measure media consumption it was used five items related with the frequency of the following behaviors: watch sports on TV; listen to sports on the radio; read sports on magazines/newspapers; access sports on Internet; and attend sports events. Sporting goods were measured based on three items related to the frequency in which they use sports shoes, buy sportswear and buy practice support material. The items regarding to media consumption and sporting goods were measured through a 7-point Likert-type scale, anchored by totally disagree (1) and totally agree (7). Finally, participation frequency was measured using 3 items related to the number of hours and times per week and number of years of practice. Responses to these items were open-ended.

Procedures

The data collection took place over a period of 4 months. Regarding participants of team and individual sports, the first procedure was to arrange a meeting with the corresponding team's coach, in order to explain the survey and request permission to carry it out. The sports considered were handball, basketball, volleyball, track and field and orientation. These sports were chosen due to the considerable number of existing adult players from both genders in Madeira Island and it includes individual and team sports. Other sports not formally mentioned were covered on a lower scale for the sample. Regarding to the fitness exercisers, the first procedure was to arrange a meeting with the directors of the gyms, to explain the survey and request permission to contact directly the people who attended the gym. In the outdoor activities, the participants practiced jogging, cycling and swimming. These participants were directly contacted and the study was explained. The survey was self-administered by all the participants after the practice, in the presence of the interviewer. The questionnaires were completed at that moment and returned to the surveyor after completion.

Statistical Analysis

A two-step maximum likelihood structural equation modeling procedure was performed using AMOS 18.0. First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm the measurement model (construct validity of the measures). Reliability of the constructs was estimated through Cronbachs alpha coefficients and values above the recommended .70 criterion were considered reliable (Nunnally & Berstein, 1994). The average variance extracted (AVE) was estimated to evaluate convergent validity and values greater than .50 were considered to demonstrate convergent validity (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2005). Discriminant validity was assumed when the average variance extracted of each construct was greater than the squared correlation between that construct and any other (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Secondly, the structural model estimation was performed to test the research hypotheses. The appropriateness of the data to both measurement and structural models was estimated through a variety of goodness-of-fit indices. Specifically, a good fit of the models was assumed when Chi-square (χ²) was not statistically significant (p > .05), the ratio of χ² to its degrees of freedom was less than 3.0, and comparative-of-fit-index (CFI) and goodness-of-fit-index (GFI) were higher than .90 (Hair et al., 2005). A root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value less than .06 was indicative of good fit while an acceptable fit was assumed for values between .08 and .10 (Byrne, 2000).

RESULTS

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis showed that the factor loading of one of the participation frequency subscale failed to exceed the cut-off point of .50 (Hair et al., 2005) and consequently was eliminated from further analysis (see Table 1). The final measurement model consisted of 14 items (four items for commitment, two for participation frequency, three for consumption of sporting goods, five for media consumption). In Table 1 it is also possible to observe that the Cronbachs alpha coefficients supported the constructs reliability, ranging from .83 (commitment) to .89 (media consumption). Convergent validity was accepted for all constructs given the average variance extracted values met accepted levels ranging from .55 (commitment) to .79 (participation frequency).

Descriptive statistics for the constructs and its correlations are reported in Table 2. The commitment had the highest mean score (M = 4.10, SD = 0.78), while media consumption had the lowest mean score (M = 3.89, SD = 1.86). Evidence of discriminant validity was accepted since none of the squared correlations exceeded the average variance extracted values for each associated construct.

In addition, the final measurement model indicated an acceptable fit to the data: χ²(81) = 331.885, p = .000, χ²/df = 4.097, CFI = .965, GFI = .951, RMSEA = .059. The χ² statistic was significant (p < .001) and its ratio to the degrees of freedom was higher than 3.0 (Hair et al., 2005). Still, it is important to consider other indexes given that the χ² statistic is sensitive to sample size (Hair et al., 2005). Both comparative-of-fit index and goodness-of-fit index values met the recommended criteria for good fit (Hair et al., 2005). Based on these overall findings, the final measurement model was within the required criteria and the constructs showed good psychometric properties. Consequently, the structural model was examined including a test of the overall model fit as well as individual tests of the relationships among latent constructs (Hair et al., 2005).

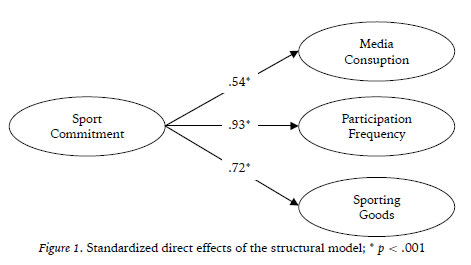

The examination of the structural model indicated an acceptable fit to the data: χ²(82) = 375.138, p < .001, χ²/df = 4.57, CFI = .95, GFI = .94, RMSEA = .06. Both comparative-of-fit-index and goodness-of-fit-index values meet the recommended criteria for good fit. The path coefficients are illustrated in Figure 1. Sport commitment influences positively the media consumption (β = .54; p < .001), supporting H1. Also, sport commitment influences positively both sporting goods (β = .72; p < .001), and participation frequency (β = .93; p < .001), confirming H2 and H3, respectively. Other important results were: 14% of the variance of participation frequency (R² = .14) was explained by commitment; 7% of the variance of media consumption (R² = .07) was explained by commitment and 18% of the variance of sporting goods (R² = .18) was explained by commitment.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this investigation was to study the relationship between sport commitment and three types of sport consumer behavior (participation frequency, media and the sporting goods consumption). Both the measurement model and the structural model indicated an acceptable fit to the data. Regarding the relationship between commitment and consumer behavior, the findings supported the three hypotheses. Sport commitment influences positively the participation frequency, media consumption, and the sporting goods consumption, being the influence of commitment stronger in participation frequency.

In the first hypothesis, sport commitment influenced positively participation frequency. The high average value of commitment (Table 2) indicates that this sample was highly committed with sports. This is an interesting fact, since the sample is representative of several sports, some with very different competitive levels. A total of 14% of the variance of participation frequency (R² = .14) was explained by commitment. This is consistent with the study of Casper and Stellino (2007), in which 16% of the variance of participation frequency was explained by sport commitment. Although a great amount of variance is still unexplained, these findings support the popular notion that highly committed sport players play more often than other sport consumers (Casper & Stellino, 2007). If the players play more often they improve their practice (Casper, 2007). Analyzing this issue in light of the theory of social exchange, underlying sport commitment, it is suggested that if the participant feels the improvement in sports, they may consider this a benefit (intrinsic reward) and, therefore, they will continue to participate in the sport as long as the results of their participation is considered a positive experience, where the benefits to the sport outweigh the costs (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). The time that the participant dedicates to the practice is directly related to the concept of involvement. According to Iwasakai and Havitz (2004), increased involvement in an activity leads to increased commitment in service offerings, and will also serve to retain customers. However, to increase participation frequency is not an easy task, and requires a personal investment in the sport which reflects personal resources such as time, effort, energy and sometimes money, that would be lost if participation did not continue (Scanlan et al., 1993). According to Scanlan et al. (1993), the personal investment is an antecedent of sport commitment, and the higher the personal investment, the higher the commitment. Furthermore, with the increase of participant frequency, social relations will be stronger and may serve as a link to continue in sports.

In the second hypothesis, sports commitment influenced positively media consumption. This finding suggests that marketers must find strategies to increase the commitment of sport consumers, because this will influence the levels of media audiences. They must understand what are the benefits derived from observation of the media so as to approach the consumer for this type of consumption. However, only 7% of the variance of media consumption was explained by commitment. Certainly there are more variables influencing media consumption. Still, knowing that participant commitment influences in some manner this type of consumption is an improvement to a better understanding of the antecedents of media consumption. According to Funk et al. (2003), previous studies have focused on sporting events, but it is also very important to study consumers that watch sports on television as well as other media consumers (e.g., internet). With television ratings and the related contracts becoming so important to sport organizations, there ought to be efforts in understanding the television consumer. Therefore, increasing the media consumption is essential for the success of sports organizations.

In the third hypothesis, sport commitment influenced positively sporting goods consumption. This result may help sport organizations in developing strategies that aid to commit the participants, as well as for creating ways of encouraging the purchase of sporting goods directly in their organizations. In our study, 18% of the variance of sporting goods was explained by sport commitment. This explained variance is the highest of the three types of sport consumption studied. This value was the same as the one found by Casper and Stellino (2007) when they explained the purchase intention of hard and soft goods through commitment. These authors concluded that highly committed tennis players are more likely to spend more money on tennis equipment. Also, Casper (2007) found that if the participants' skill level increases, they will purchase more goods, adequated to his/her level. Analyzing sporting goods average items, it was found that using sports shoes presents a higher average followed by sportswear and lastly the purchase of support material. Knowing that these values are on a scale from 1 to 7, it is noted that, with the exception of sports shoes, these tend to be placed in the middle of the scale. Probably many participants associate sport shoes not only to sports but also with a specific lifestyle.

There are limitations in this study that should be acknowledged for future research. First, the participants were surveyed at one point in time. Longitudinal research has found that commitment levels change over time (Carpenter & Coleman, 1998; Carpenter & Scanlan, 1998). Therefore, future research should collect data in panel-type surveys where it is possible to track individual attitudes and behaviors over time (Iwasaki & Havitz, 2004) in order to better understand the relationship between commitment and the various products. Second, the sample was limited to Madeira Island. Future research should be extended to other sports and collect larger samples of sport consumers. Third, this study focused on the construct of sport commitment but did not assess its antecedents. Additional research addressing the commitment model including its antecedents may be useful to better understand sport consumer behavior. Although the study of enjoyment was not analyzed, it may be important to include this variable in future research since it is understood as the most predictive variable of commitment (Casper, 2007; Guillet, Sarrazin, Carpenter, Trouilloud, & Cury, 2002; Wilson et al., 2004).

CONCLUSIONS

In general, it is accurate to say the findings supported the three hypotheses. The commitment influenced positively participation frequency, sporting goods and media consumption. 18% of the variance of sporting goods consumption, 14% of the variance of participation frequency and 7% of the variance of media consumption was explained by commitment. These results serve as initial statistical evidence of the relationship between sport commitment and different types of consumption. It is fundamental to the sport marketers to update knowledge about the consumers, in order to plan retention strategies and establish new relations between the consumers and sports products. The implications of these results show that marketing efforts to increase the commitment of participants should help to increase the participation frequency, the consumption of sporting goods and the media. This can help service providers to understand market segmentation based on commitment, yet these findings should be used with caution since the sample in study is representative of a specific population. This investigation contributed to the study of sport commitment in adults.

REFERÊNCIAS

Beasley, F., Shank, M., & Ball, R. (1998). Do Super Bowl viewers watch the commercials? Sport Marketing Quarterly, 7(3), 33-40. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2000). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Carpenter, P., & Coleman, R. (1998). A longitudinal study of elite youth cricketers' commitment. International Journal Sport Psychology, 29, 195-210. [ Links ]

Carpenter, P., & Scanlan, T. (1998). Changes over time in the determinants of sport commitment. Pediatric Exercise Science, 10, 356-365. [ Links ]

Casper, J. (2007). Sport commitment, participation frequency and purchase intention, segmentation based on age, gender, income and skill level with US tennis participants. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(3), 269-282. [ Links ]

Casper, J., & Stellino, D. (2007). A sport commitment model perspective on adult tennis players' participation frequency and purchase intention. Sport Management Review, 10, 253-278. [ Links ]

Casper, J., & Stellino, D. (2008). Demographic predictors of recreational tennis participants` sport commitment. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 26(3), 93-115. [ Links ]

Dwyer, B., & Drayer, J. (2010). Fantasy sport consumer segmentation: An investigation into the differing consumption modes of fantasy football participants. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 19, 207-216. [ Links ]

Fisher, E. (2008). Study: Fantasy players spend big. Street Smiths Sport Business Journal, 11(29), 1-2. [ Links ]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(35), 39-50. [ Links ]

Fullerton, S. (2007). Sport marketing. Michigan: McGraw-Hill/Irwin Published. [ Links ]

Funk, D. (2008). Consumer behavior in sport and events: Marketing Action. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Funk, D., Mahony, D., & Havitz, M. (2003). Sport consumer behavior: Assessment and direction. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(4), 200-205. [ Links ]

Guillet, E., Sarrazin, P., Carpenter, P., Trouilloud, D., & Cury F. (2002). Predicting persistence or withdrawal in female handballers with social exchange theory. International Journal of Psychology, 37(2), 92-104. [ Links ]

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2005). Multivariate data analyses (6th ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Hau, L. (2008). TV`s most influential sportscasters. Retrieved 29 July 29 from: http://www.forbes.com/2008/01/28/television-sports-madden-biz-sports-cx_lh_0128broadcasters.html [ Links ]

Iwasaki, Y., & Havitz, M. (2004). Examining relationships between leisure involvement, psychological commitment, and loyalty to a recreation agency. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(1), 45-72. [ Links ]

Kim, Y., & Trail, G. (2011). A conceptual framework for understanding relationships between sport consumers and sport organizations: A relationship quality approach. Journal of Sport Management, 25, 57-69. [ Links ]

Meir, R. (2000). Fan reaction to the match day experience: A case study in English professional rugby league. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 9(1), 34-42. [ Links ]

Neale, L., & Funk, D. (2006). Investigating motivation, attitudinal loyalty and attendance behaviour of Australian Football. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 7(4), 307-316. [ Links ]

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Plunkett, J. (2008). Plunkett`s sport industry almanac 2008: Sport industry market research, statistics, trends & leading companies. Houston, TX: Plunkett Research. [ Links ]

Pitts, B., & Stotlan, K. (2002). Fundamentals of sport marketing (2nd ed.). Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology. [ Links ]

Redden J., & Steiner, C. (2000). Fanatic consumers: Toward a framework for research. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(4), 322-337. [ Links ]

Scanlan, T., Carpenter, P., Schmidt, G., Simons, J., & Keeler, B. (1993). An introduction to the sport commitment model. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 15, 1-15. [ Links ]

Shank, M. (2004). Sports marketing: A strategic perspective. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Stewart, B., Aaron, C., Smith, T., & Nicholson, M. (2003). Sport consumer typologies: A critical review. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(4), 206-216. [ Links ]

Thibaut, J., & Kelley, H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Trail, T., Robinson, M., & Kim, Y. (2008). Sport consumer behavior: A test for group differences on structural constraints. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 17, 190-200. [ Links ]

Weiss, W., & Weiss, M. (2006). A longitudinal analysis of commitment among competitive female gymnasts. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7, 309-323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.08.010 [ Links ]

Westerbeek, H., & Smith, A. (2003). Sport business in the global marketplace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Wilson, P., Rodgers, M., Carpenter, P., Hall, C., Hardy, J., & Fraser, S. (2004). The relationship between commitment and exercise behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5, 405-421. doi: 10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00035-9 [ Links ]

Correspondence to: Norberta Elisa Fernandes, Faculdade de Motricidade Humana - Universidade de Lisboa, Estrada da Costa, 1499-002 Cruz Quebrada - Dafundo, Portugal. E-mail: norfernandes@hotmail.com

Agradecimentos:

Este trabalho foi elaborado com o apoio parcial do Governo Regional da Madeira, através de uma equiparação a bolseiro, durante dois anos (2009/2010, 2010/2011), ao primeiro autor.

Conflito de Interesses:

Nada a declarar.

Financiamento:

Nada a declarar.

Submitted: 08.03.2012 | Accepted: 05.01.2013