Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Motricidade

versão impressa ISSN 1646-107X

Motri. vol.14 no.4 Ribeira de Pena dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.14982

ARTIGOS ORIGINAIS

Perception A retrospective analysis of career termination of football players in Portugal

António Carapinheira1, Miquel Torregrossa2, Pedro Mendes3, Pedro Guedes Carvalho4,5, Bruno Filipe Rama Travassos1,5[*]

1University of Beira Interior, UBI, Covilhã, Portugal

2University Autónoma of Barcelona, UAB, Barcelona, Spain

3Instituto Português de Administração de Marketing, IPAM, Porto, Portugal

4Superior Institute of Maia, ISMAI, Castêlo da Maia, Portugal

5Research Center in Sports Sciences, Health Sciences and Human Development, CIDESD, Vila Real, Portugal

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to analyse the retirement of elite football players in Portugal. Specifically, the quality of retirement and the resources available were evaluated. To develop an understanding of the process of the sporting retirement of elite football players we used data from in-depth, semi-structured interviews with ninety professional players that played in football national team. Fifty per cent of the elite Portuguese footballers retired from sport between 36 and 40 years of age (M = 35.53 ± 3.63 years), their retirement had been involuntary and it had taken them less than a year to accept retirement. Most had only been educated to secondary level and had a strong athletic identity; no plans for their post-football career exist and relied on family as their main psychological support. None of the players had received support from a formal programme. Despite of the findings being consistent with previous research from other Southern European cultures, it seems that the athletic retirement of Portuguese footballers has some particularities.

Keywords: career transition, post-retirement career, quality of termination, coping strategies, psychological support.

Introduction

Transition from a sports career is a process that is influenced by the athlete’s situation, self, the support available and individual use of strategies (Erpič, Wylleman, & Zupančič, 2004; Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler, & Côté, 2009). According to Stambulova (2009) the transition from a sports career involves a coping process that is facilitated by a combination of contextual factors and athlete’s resources (i.e., internal or external factors such as the athlete’s past experiences, motivation and social and financial support). Therefore, career transition is a large research topic that encompasses research on adjustment of athletes to their new life and the athletic and non-athletic factors that contribute to their success (Stambulova & Ryba, 2014).

Athletic termination has been a hot topic in sports career transition research in recent years due to the high number of athletes experiencing serious financial, social and psychological difficulties at the end of their athletic career (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007; Park, Lavallee, & Tod, 2013). In this context, athletic termination has been studied as a process that requires former athletes to adjust to a new psychological, social, familiar, occupational, and even financial status (Stambulova et al., 2009; Wylleman, Alfermann, & Lavallee, 2004).

Theoretical framework

Although approaches to research on the career transition process have varied over the years, athletic termination has always been a topic of interest due to the societal concerns about athletes’ adaptation to their new life (Alfermann & Stambulova, 2007). According to Stambulova and Ryba (2014) there are three main theoretical frameworks applied to sport career research of the sport career transition process. Each

theoretical framework focuses on different aspects of career transition process. The first approach were based on thanatology perspectives (stages if dying) and the moment of termination was viewed as a negative and traumatic single event that changes the course of life of the participants (Schlossberg, 1981). After that, the athletic retirement model (Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994) was proposed to study specifically on athletic termination and the factors and resources that contribute to the quality of athletic termination and is particularly relevant to understanding of elite athletic termination. The athletic termination model comprises five categories of factor: (a) initiation of athletic retirement, (b) adaptation to athletic retirement,

(c) the athlete’s resources, (d) quality of athletic retirement and (e) interventions to support the retirement process. At the end, the holistic model of athletic careers (Wylleman, Reints, & De Knop, 2013) focuses on analysis of the academic, athletic, individual, psychological and academic transitions athletes undergo. That is, proposed a holistic, lifespan, multi-level approach to improve the understanding of the contextual factors in career development and transitions (Stambulova et al., 2009).

Athletic termination

In line with the athletic retirement model recent studies have provided evidence that athletic retirement is a process that is mediated by non-athletic factors (i.e., social factors and life events) that should be recognised as constraints of quality of life after an athletic career (Stambulova et al., 2009; Torregrosa, Ramis, Pallarés, Azócar, & Selva, 2015). Park et al. (2013) concluded that to understand the process of career termination it is necessary to understand the factors affecting quality of post- termination career and the resources available to athletes during the termination process. There is strong evidence, for instance, that voluntary termination is associated with good adaptation to a new life and a shorter transitional period (Agresta, Brandão, & Barros Neto, 2008; Park et al., 2013). In contrast involuntary termination due to age, deselection or injuries can contribute to difficulties with adaptation to termination, including dissatisfaction with the sudden change and negative emotional reactions to it, as well as difficulty with accepting one’s new life (Stambulova et al., 2009; Wylleman et al., 2004). Overall the research has revealed that: (a) there are multiple motifs for athletic termination and it is the outcome of a reasoned decision- making process; (b) the more control that athletes feel they have over the decision to retire, the better their adaptation to post-termination life; (c) the process of adapting to athletic termination is highly individual and hence there are large inter-individual differences in the outcome; (d) planning for termination is crucial to coping successfully with one’s new life; (e) the skills and social support an athlete has are crucial to the adaptive process.

In addition, it has recently been highlighted out that athletic termination is not a purely rational decision but is also driven by emotion, compulsion and a need to be part of the game. These feelings can be associated with the loss of identity during and after athletic termination, due to loss of value of previous experiences and acquired competences during athletic career (Cosh, LeCouteur, Crabb, & Kettler, 2013). Previous research revealed that many former athletes expected to make the transition from an athletic career to a sports-related career, because they felt that they have the necessary knowledge, experience and competence to perform in this context (Cushion, Armour, & Jones, 2006). It would be interesting to investigate whether elite athletes’ expectation that they will continue to work in their sport helps them to maintain their athletic identity and reduces negative feelings about athlete termination process (Fernandez, Stephan, & Fouquereau, 2006; Mihovilovic, 1968).

There have been few studies evaluating the athletic termination of football players and almost all of them used small samples (D’Angelo, Reverberi, Gazzaroli, & Gozzoli, 2017; Rintaugu, Mwisukha, & Monyeki, 2016; Sanders & Stevinson, 2017). Nevertheless, recent studies revealed that whilst a minority of retired Italian football players retired from the sport voluntarily and continued to be involved in football-related activities (D’Angelo et al., 2017), most Kenyan retired football players retire voluntarily and continue to be involved in football subsequently (in coaching, sports marketing or sports administration) (Rintaugu et al., 2016). Thus, previous studies have emphasised the need to understand how nationality and culture influence athletic termination (Dimoula, Torregrosa, Psychountaki, & Fernandez, 2013). For instance, the analysis of the loss of identity and the mental problems associated with the moment of termination or the analysis of the existence of a pre-termination plan or the psychological support required (Dimoula et al., 2013; Jones & Denison, 2017; Park et al., 2013; van Ramele, Aoki, Kerkhoffs, & Gouttebarge, 2017) in specific countries or the comparison between different countries and cultures should be considered in further studies. In Portugal there has been scant research interest in this topic and in recent years some attempts have been made to develop programmes to support athletes during the termination process. Thus, although previous research on athletic termination, it is essential to develop research on athletic termination in Portugal in order to understand the specific social factors affecting the process and contributing to develop appropriate policies and support programmes (Levitt et al., 2018).

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to identify the motifs of sporting termination in elite Portuguese Football players. Following the suggestions of Park et al. (2013) in this study it was evaluated the: (a) factors affecting the quality of the transition from athletic career to post- athletic career and (b) resources available to elite football players during this transition.

Method

Participants

Ninety male Portuguese former elite football players participated in this study (M = 50.68 ± 9.14 age). Three criteria were used for participants selection: (a) professional male football Portuguese players; (b) participation of the national team as senior football players, and (b) career termination from football between 1985 and 2015. Most had retired from competition at the age of 36 - 40 years (35.53 ± 3.63 years) and slightly more than half had played professionally for 16 - 20 years (M = 16 ± 3.12 years as professional players). Most had only been educated to secondary level (53.3%). Interestingly, the current occupation of 97.8% of these retired football players was football-related, with the biggest group being football coaches. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University Ethics Committee. Participants were informed that information from interviews would be confidential and used only for research. All the participants were informed of the purpose of the study and provided written, informed consent.

Instruments and Procedures

A semi-structured interview guide in Portuguese based on the athletic termination model was developed. The interview was focused in two themes of questions after the collection of demographic information, based on the proposal of Taylor and Ogilvie (1994) and in line with the previous systematization of Park et al. (2013): (a) quality of career transition, (b) resources for career transition (Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994). In the analysis of quality of career termination five dependent variables were accessed: voluntary termination (participants were asked about the reasons for career termination and about the voluntariness about the decision), athletic identity (participants were asked about other activities that they have developed during their career, their concerns with the termination and their motivations while players), the time taken to accept termination (participants were asked about the time that they needed to accept termination), career / personal development (participants were asked about the strategies that they used to improve their career in the future and how previous knowledge help them on that) and life changes (participants were asked about bout their experience of transition to termination and the difficulties they feel). The analysis of available resources for career termination comprising four dependent variables: coping strategies (participants were asked about the strategies used to react to the sport termination situation and to define the most relevant), psychological support (participants were asked about the person(s) that support him psychologically), pre-termination planning (participants were asked about the existence of a termination plan) and support program involvement (participants were asked about the existence of support programmes that help them on the termination process and their opinion about the importance of such programs).

The interview has been previously validated according to qualitative methods (Vaivio, 2012). The interview structure has been validated to ensure the reliability of the collected data. The final interview was developed after exploring previous drafts of the transcript using the following steps: (a) Adaptation of first draft of the interview based on previous studies; (b) Evaluation and adjustments on the interview by two senior researchers in sports sciences, who have substantial experience with interviews; (c) Development of a pilot study conducted with three former professional football players (d) Minor fixes and adaptations resulting from the pilot study; (f) Definition of the final version of the interview. Semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face in a calm environment (usually in a hotel meeting room). Interviews (lasting 45 - 90 mins) were carried out by the first author and audio-recorded with the informed consent of participants and then transcribed verbatim.

From the semi-structured interview data were extracted and organized with a deductive approach to the content according to the themes and the dependent variables previously defined. After a line-by-line analysis, transcripts were read repeatedly for familiarization and text units were codded and organized into specific categories. The descriptive and theoretical validity were ensured through a process of triangulation by all the authors. Software NVivo 10 was used to organize data codification and analysis (Bazeley & Jackson, 2013).

Results

In line with the previous work of Park et al. (2013) the analysis was divided into two main themes: (a) quality of career transition; and (b) resources for career transition. These categories were further divided into dependent variables that characterize the termination of the athletic career of elite Portuguese football players.

Quality of career termination

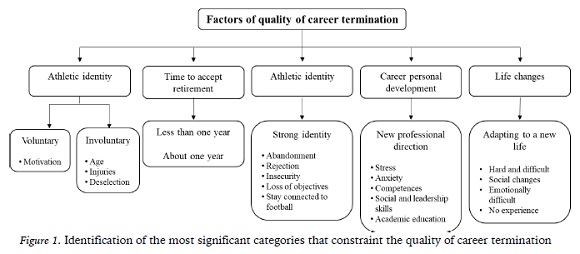

Figure 1 represent the most significant categories obtained for each dependent variable related with the quality of career termination.

Voluntary termination.

For the majority, athletic retirement had been involuntary. Age was the causal factor cited by the greatest proportion of participants. Also, the injuries and deselection was considered a motif for involuntary retirement.

“I was 37 years old and I was fed up with my football playing career. I didn’t feel the same physical and mental capacity to answer to the training and game requirements. I was emotionally tired.” (Player 33)

“With the increase in my age I didn’t feel the same pleasure to continue playing. I want to continue playing but it was very hard for me” (Player 45)

“I was physically and emotionally tired because had a lot of injury problems during my career and in last years the problems have increased” (Player 73)

“In last year of my career I cannot play as I like because I didn’t felt capacity to train and play at high intensity. I was always recovering from injuries. It was very difficult for me” (Player 22).

In opposition, about a third of the sample reported that they had retired voluntarily. Lack of motivation was the causal factor cited by the greatest proportion of participants.

“I left on my own initiative, it was the right time to finish. It didn’t have the same motivation to keep on as a football player and I focus my energies in other projects. It was the right moment” (Player 15)

“In the last months I didn’t feel the same pleasure to continue training and competing. The time to go to the training sessions become an obligation because I no long have motivation to continue and I no longer identified myself with that context” (Player 3).

Time to accept termination.

Speaking about how long it had taken to accept athletic termination the majority of participants reported that the acceptance had been immediate or taken less than one year. However, some of them reported a year or more to accept the termination, even maintain the link with the sport or starting new activities during this time.

“I accepted immediately that it was time to retire. The days after termination were difficult but I accepted my termination as a normal process of life. However, I think that I benefited the fact that I have a proposal to continue working in football” (player 15)

“It took me some time to accept. Maybe about one year because I wanted to keep playing and I could not accept the idea even starting another job in the area of football” (player 45)

“Until now it has been difficult to accept that I’m no longer a football player. I fell that lost my dream” (player 30).

Athletic identity.

The participants reported strong athletic identity. That is their main focus was the activity as professional football player and any one of them reported the practice of dual-careers.

“While I was a football player I did not have to think about the future and I thought that my career would be longer” (Player 28)

“Being a public figure made me feel I would not need to prepare myself for a new career. In my mind, I was above everyone and I think that at the end of my career something positive would happen to me” (Player 84).

Due to the strong athletic identity, the former athletes referred feelings of abandonment, rejection and insecurity after termination. The loss of objectives for the future was also identified as a common feeling reported by the participants.

“I felt abandoned. I felt that people start looking at me differently. It was very weird and difficult” (Player 80)

“I felt frustrated and I didn’t know what to do next. I had never dealt with similar feelings like the ones I felt after termination” (Player 33)”

“I had some money, but I didn’t know what to do in my life or with the money that I have. I didn’t have objectives for the future because it seems that my life was ended” (Player 45)

“I was approached by some opportunists who suggested I should get involved in something but I wasn’t interested in it and I didn’t care about the opportunities that they suggest me. However, due to the facilities I still got involved” (Player 3).

In line with the strong athletic identity, the participants reported the benefits to have the opportunity to stay connected to football. Interestingly, they feel that it helps to improve the quality of athlete termination. The main reasons reported for staying connected to football were intrinsic motivations, such as having a passion for football, wanting to transmit values and spirit in football and wanting to transmit acquired knowledge and the previous experience accumulated

“I always be interested in the training and the management in football and that meant the door was open for me to continue in the football area. I always wanted to stay connected to football. It helps to make the career transition easy” (player 80)

“The identification of a possibility to develop a new work in the field of football helps me to maintain my confidence. I think that I know everything about football and nothing about the other professions” (player 61)

“Passion. This is an area that I know, and I loved to work on it. I have great passion for football and I’m really happy to continue contributing to the development of the sport. I wanted to transmit all my knowledge and values to youngers” (player 17)

“I have just specialized in this sport. It is my life and I don’t imagine me out of it” (player 27).

Former players also mentioned that some opportunities to work in football emerged immediately after career termination or even during the last moments of their career as players.

“It was the moment and the opportunity for athletic termination and to start a new job in the club. When I retired I started a new career at the club. I think that my knowledge of the game and the about the environment that surrounds the sport contributes to the continuity in the club” (player 73)

“I had the opportunity to become a coach and I am enjoying it. I had to change my perspective about the game and I had to study about the coaching process, but it is very challenging, and I still feel that I am part of it” (player 12).

Career/ personal development.

Some participants reported that the need to find a new professional direction after termination had caused anxiety and difficulties after the termination. In contrast another group reported that personal development and the competences and values they had acquired during their athletic career were very important for their termination because they helped them to feel valuable. The academic education on termination was also mentioned as a good way of improving quality of termination

“I needed to find a new occupation and I didn’t know what I should do more than to be linked with football. It was stressful and very difficult for me, but when I received an opportunity to work in football I try to catch her with both hands. Even today I didn’t imagine me doing another thing and it causes me some stress” (player 88)

“I put the values I have learned during my career into practice to help me to overcome the difficulties in my new life. My social and leadership skills were very important and led to help me in the new functions” (player 4)

“It was important to find an occupation and for me that meant enrolling in the graduate program” (player 16)

“The development of new skills and the frequency of the coach graduation program was very important for me. It helped to accept the termination and contributed to the development of new skills that I needed in the future as a coach” (player 12).

Life changes.

Mostly of participants reported that adapting to a new life was hard and causes mental and physical stress. Also, the absence of competition, training, friends and routines also promotes difficulties on the process of transition.

“I found it difficult to adapt to a new life. The new functions and requirements of the new job were not difficult to accomplish but we also need to consider the social changes that our life suffers. It was a mix of feelings and changes that I didn’t expected felt” (player 33)

“I felt stressed, I could not think to myself that all was finished. Initially it was very difficult emotionally. I was feeling very anxious and annoyed” (player 82)

“I missed the friends, the training, the teammates and the football. I was afraid of the future because I was worried about being unemployed. I didn’t have any academic qualification or experience (player 88).

Available resources

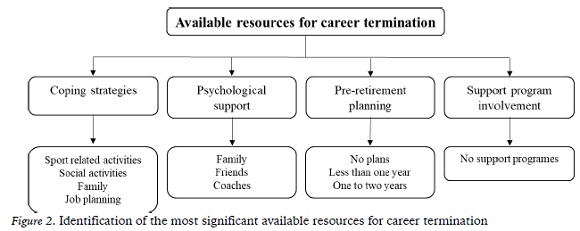

Coping strategies.

The coping strategies employed by participants included dedicating time to sport- related activities such as coaching or scouting, followed by time dedicated to family and social support activities. Few of them reported the use of time to entrepreneurial activities and job planning.

“I used to dedicate my time to family and I was also involved in some sport activities and to help institutions that worked with young children” (player 2)

“After to my family, all of my time was dedicated to watch games and analyse players. I felt that it could help me for the future and I was right.” (player 91)

“Apart from the family, I had personal investments that I try to maintain and improve” (player 78)

“I tried to define a plan for the future and I started to talk to people that could help me on my future. The contacts that I created as a football player help me a lot” (player 61).

Psychological support.

Family was the most important source of psychological support and counselling, followed by friends and coaches.

“My family was very important for me. They really helped me to understand my new situation” (player 56)

“My real friends give me good advice and help me to stay focused on the future” (player 29)

“There was an experienced coach that helped me a lot and opened my mind in relation to the future” (player 34)).

Pre-retirement planning.

Most participants reported that had not planned their termination, referring that they adjust their decisions in less than one year until termination or that they had never thought carefully about their termination beforehand. A few number of participants reported that they had started to plan their termination two to four years in advance or had been planning for termination throughout their career.

“I did not think about it. The, after the moment of termination the problems started to appear” (player 11)

“I started to think about my termination in the last five or six months of my playing career. I knew it would happen but in the beginning of my career I do not think about it. Really, I didn’t want to think too much about it.” (player 72).

Support program involvement.

All the participants reported that there were no support programmes for retired footballers in Portugal. Participants felt that such support programmes could offer valuable support in several areas such as counselling and planning for the future, development of professional and financial decisions or academic and professional education. Furthermore, a great number of participants suggested that such programs should contribute since the beginning of their careers for the development of dual-careers.

“Support programs should help to find an orientation and help us to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of our decisions” (player 10)

“It would be important for emotional and financial management and also to provide professional tools for a future job” (player 13)

“It is important to provide academic formation and to develop alternatives for the future since the beginning of players career” (player 44)

“The development of programmes of dual careers should enable us to learn different skills such languages, informatics, economy, psychology. It should enable us to manage our career, help us with personal financial management and most importantly prepare us to the future” (player 60).

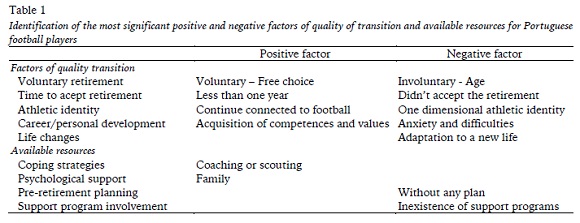

Table 1 summarises the findings on athletic retirement in terms of the two themes evaluated. Based on previous research, it was highlighted for each variable the categories that contributes for a more positive or negative termination.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of the process of retiring from professional sport and the resources available to elite football players in Portugal. Our analysis of interview data from a sample of ninety elite Portuguese footballers is consistent with the pattern of athletic termination that has emerged from other research on athletes in Southern European cultures (Dimoula et al., 2013). The transition is characterised by maintenance of a strong athletic identity, difficulty adapting to one’s new life and predominance of relocation in sports. The commonly available coping resources were participation in sport activities, support from family and friends. However, at the same time, it was reported a general lack of termination planning and absence of formal support programmes.

The participants retired from sport between 36 and 40 years of age. Their career termination had been involuntary, and it had taken them less than a year to accept termination. Most had only been educated to secondary level and had a strong athletic identity. A great number of participants reported a lack of plans for their post-football career and relied on family as their main psychological support. None of the players had received support from a formal programme.

Quality of transition

Our sample of elite Portuguese footballers retired later than Kenyan footballers (Rintaugu et al., 2016), the footballers that participated in the study by van Ramele et al. (2017) and also later than Greek and Spanish elite athletes in general (Dimoula et al., 2013). Hence our participants had spent more years in professional sport than the athletes in these other studies. Such results can be related with the strong athletic identity of elite Portuguese football players and with the general lack of plans for their post-football career. For instance, (Ramos, López de Subijana, Barriopedro, & Muniesa, 2017) revealed in this line of reasoning that dual career athletes usually abandon their careers four to five years before players with a career only focused in sport. Also, active elite players usually develop with more clarity an image of termination with a plan associated in comparison with players with a career only focused in sport (Torregrosa, Boixadós, Valiente, & Cruz, 2004)

The most common level of education amongst our sample of retired footballers was secondary level, which is in line with previous research (Rintaugu et al., 2016; van Ramele et al., 2017). We found that 97.8% of our retired footballers had remained connected to football. They reported that this was due to intrinsic motivations, such as passion for football and desire to transmit the values of football and the knowledge they had acquired during their playing career. These results confirm the tendency of former elite athletes to maintain a professional connection with sport (Dimoula et al., 2013; Rintaugu et al., 2016), however to the best of our knowledge no previous study has reported the continued professional involvement of such a high proportion in the same sport. It is a typical behaviour of relocation in sports, instead of a complete termination from sport, and reduces stress and identity crisis after termination (Torregrosa et al., 2004). In this sense, despite of the high athlete identity observed, the negative consequences of termination could be attenuated with such relocation in sport, promoting the feeling of integration and competence for the development of the new career (Dimoula et al., 2013; Fernandez et al., 2006). Even not supported by any institutional program such strategy should be encouraged for the future with programmes of career transition support.

Most of the Portuguese footballers in our sample had not retired voluntarily. Termination had been forced on them by age, injuries or deselection. These results are consistent with observations of Italian footballers (D’Angelo et al., 2017). This contrasts with previous research in Kenyan footballers (Rintaugu et al., 2016) and in elite athletes suggesting that the majority of athletes retire voluntarily (Alfermann, 2000; Dimoula et al., 2013; Erpič et al., 2004). Such result is a bad predictive of adaptation to the new life condition (Alfermann, Stambulova, & Zemaityte, 2004; Torregrosa et al., 2015). Participants found involuntary termination difficult to cope with, due to the lack of control and loss of identity they experienced (Martin, Fogarty, & Albion, 2014; Torregrosa et al., 2015). These difficulties may be partly due to lack of preparation for the end of one’s sporting career and the short time that athletes reported. The postponement of a voluntary termination delays the plans for the future and athletes’ acceptance of termination and emotional reaction to it is different when termination is involuntary.

More than half of our sample struggled to adapt to their new life and experienced mental and physical disorders. The emergence of negative feelings and mental and physical disorders at the time of athletic termination is typical of involuntary terminations (Park et al., 2013). Nevertheless most of our participants reported that it had taken them less than a year to accept termination, which is less time than reported in most previous studies (Park et al., 2013). The relatively rapid acceptance of athletic termination that we observed is probably due to the fact that most of our participants had moved into a new professional career related to football, so in this sense they had not retired from the sport. The faster integration in a new life related with the practiced sport contributes to maintain high social recognition and feeling of competence (Torregrosa et al., 2004). Recognising the competences their athletic career has given them allows athletes to capitalise on their transferable skills in a new career and is empowering for players.

Resources for coping with the transition

The results of this study revealed that the available resources to face career termination are common between south European Cultures. A lot of cross-culturally common characteristics were observed between sports (Stambulova et al., 2009). It was observed that players’ preferred coping strategies involved participation in sport and development of a new sport-related career, which is a common finding in retiring athletes (Dimoula et al., 2013; Rintaugu et al., 2016). Focusing on developing a new career appears to facilitate adaptation to athletic termination and reduces the risk of misuse of drugs and alcohol (Alfermann et al., 2004; Park et al., 2013). In this process of adjustment to the new life, the participants referred the importance of psychological support from non-sporting agents (family’s role, self, friends). As previously observed, psychological support helps retired athletes to maintain a positive emotional state and improves the quality of their career transition.

However, most participants reported that they had done no preparation for their post- football life and others reported that they had only started to prepare for their subsequent career towards the end of their playing career and the self-consciousness. It seems that athletes ignore or the problem of termination or try to postpone it in order to remain focused on the competition (D’Angelo et al., 2017; Rintaugu et al., 2016). Lack of knowledge about the transition process may lead to difficulties during the process (Park et al., 2013). Despite of that, most participants in the study show concerns and negative feelings regarding their future (Alfermann et al., 2004).

One of the most important ways of promoting a rapid and positive transition from playing professional sport is to offer dedicated support programmes (Erpič et al., 2004; Park et al., 2013). However, any support program integration was reported by participants, in line with the other European countries (Dimoula et al., 2013; Stambulova et al., 2009). Although there always existed several attempts to develop and promote supportive programs for professional footballers it seems that players do not know or do not use such training possibilities in Portugal. In line with other studies, several participants reported that the lack of financing support and qualified people to develop further support programmes may increase the risks of participation (Park et al., 2013). However, they would like to have such support and reported that support programmes should be developed for counselling and consciousness regarding the future and support to help professional and financial decisions.

Further studies should compare and correlate the factors that characterize termination with the quality of termination of different groups of participants and levels of performance. This would enable the identification of factors that constraint the quality of termination. There is also a need for evaluations of other transitions in an athlete’s career, such as the transition from junior to senior level. We hypothesize that there will be clear differences between the different career transitions. At the end, as a limitation of this study we should report the non- identification of the time between termination and participation in the research. It was reported as a variable that could influence results. Also, our sample was only constituted by elite Portuguese football players. It is required that further studies increase the sample of participants to compare the reality of players of different levels of practice. For instance, there is a need to understand how the high level of practice of players constraint their quality of transition and available resources.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed that termination of elite Portuguese footballers has general similarities with European Southern Countries but more important than that is that revealed some particularities. For instance, Portuguese footballers retired later and had longer playing careers than athletes in other countries, reported a short time to accept termination and had developed a new professional career linked to football in a short period of time. However, most of them reported that the termination was involuntarily, and experienced difficulties related with mental and physical disorders. According to that, there is a need to develop support programmes tailored to the needs of Portuguese footballers. For example, more than to develop support programs based on the moment of termination, it is suggested the development of programs that support the development of the entire career to promote dual careers and to prepare and develop a more clear image of the timing and the resources for termination and for the prospective life (Ramos et al., 2017; Torregrosa et al., 2004). The development of programs focused on the athlete lifespan instead on the moment of transition or termination will contribute to improve voluntary termination and consequently better adaptations to the new life (Agresta et al., 2008; Park et al., 2013).

REFERENCES

Agresta, M. C., Brandão, M. R. F., & Barros Neto, T. L.d. (2008). Causas e conseqüências físicas e emocionais do término de carreira esportiva. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte.

Alfermann, D. (2000). Causes and consequences of sport career termination. In D. Lavallee & P. Wylleman (Eds.), Career transitions in sport: International perspectives (pp. 45-58): Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology. [ Links ]

Alfermann, D., & Stambulova, N. (2007). Career transitions and career termination. In R. C. Tenenbaum & G. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of Sport Psychology, Third Edition (pp. 712-733). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Alfermann, D., Stambulova, N., & Zemaityte, A. (2004). Reactions to sport career termination: a cross-national comparison of German, Lithuanian, and Russian athletes. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5(1), 61-75. [ Links ]

Cosh, S., LeCouteur, A., Crabb, S., & Kettler, L. (2013). Career transitions and identity: a discursive psychological approach to exploring athlete identity in retirement and the transition back into elite sport. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health, 5(1), 21-42. [ Links ]

Cushion, C. J., Armour, K. M., & Jones, R. L. (2006). Locating the coaching process in practice: models for’and of’coaching. Physical education and sport pedagogy, 11(01), 83-99.

D’Angelo, C., Reverberi, E., Gazzaroli, D., & Gozzoli, C. (2017). At the end of the match: exploring retirement of Italian football players. Revista de psicología del deporte, 26(3).

Dimoula, F., Torregrosa, M., Psychountaki, M., & Fernandez, M. (2013). Retiring from elite sports in Greece and Spain. The Spanish journal of psychology, 16(E38). [ Links ]

Erpič, S. C., Wylleman, P., & Zupančič, M. (2004). The effect of athletic and non-athletic factors on the sports career termination process. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5(1), 45-59.

Fernandez, A., Stephan, Y., & Fouquereau, E. (2006). Assessing reasons for sports career termination: Development of the Athletes' Retirement Decision Inventory (ARDI). Psychology of sport and exercise, 7(4), 407-421. [ Links ]

Jones, L., & Denison, J. (2017). Challenge and relief: A Foucauldian disciplinary analysis of retirement from professional association football in the United Kingdom. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(8), 924-939. [ Links ]

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26. [ Links ]

Martin, L. A., Fogarty, G. J., & Albion, M. J. (2014). Changes in athletic identity and life satisfaction of elite athletes as a function of retirement status. Journal of applied sport psychology, 26(1), 96-110. [ Links ]

Mihovilovic, M. A. (1968). The status of former sportsmen. International Review of Sport Sociology, 3(1), 73-96. [ Links ]

Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes' career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International review of sport and exercise psychology, 6(1), 22-53. [ Links ]

Ramos, J., López de Subijana, C., Barriopedro, M., & Muniesa, C. (2017). Events of athletic career: a comparison between career paths. Revista de psicología del deporte, 26(4). [ Links ]

Rintaugu, E. G., Mwisukha, A., & Monyeki, M. (2016). From grace to grass: Kenyan soccer players' career transition and experiences in retirement: sport participation. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences (AJPHES), 22(1.1), 163-175. [ Links ]

Sanders, G., & Stevinson, C. (2017). Associations between retirement reasons, chronic pain, athletic identity, and depressive symptoms among former professional footballers. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(10), 1311-1318. [ Links ]

Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The counseling psychologist, 9(2), 2-18. [ Links ]

Stambulova, N., Alfermann, D., Statler, T., & Côté, J. (2009). ISSP position stand: Career development and transitions of athletes. International journal of sport and exercise psychology, 7(4), 395-412. [ Links ]

Stambulova, N., & Ryba, T. V. (2014). A critical review of career research and assistance through the cultural lens: towards cultural praxis of athletes' careers. International review of sport and exercise psychology, 7(1), 1-17. [ Links ]

Taylor, J., & Ogilvie, B. C. (1994). A conceptual model of adaptation to retirement among athletes. Journal of applied sport psychology, 6(1), 1-20. [ Links ]

Torregrosa, M., Boixadós, M., Valiente, L., & Cruz, J. (2004). Elite athletes’ image of retirement: the way to relocation in sport. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5(1), 35-43.

Torregrosa, M., Ramis, Y., Pallarés, S., Azócar, F., & Selva, C. (2015). Olympic athletes back to retirement: A qualitative longitudinal study. Psychology of sport and exercise, 21, 50-56. [ Links ]

Vaivio, J. (2012). Interviews-Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

van Ramele, S., Aoki, H., Kerkhoffs, G. M., & Gouttebarge, V. (2017). Mental health in retired professional football players: 12-month incidence, adverse life events and support. Psychology of sport and exercise, 28, 85-90. [ Links ]

Wylleman, P., Alfermann, D., & Lavallee, D. (2004). Career transitions in sport: European perspectives. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5(1), 7-20. [ Links ]

Wylleman, P., Reints, A., & De Knop, P. (2013). A developmental and holistic perspective on athletic career development. Managing high performance sport, 159-182. [ Links ]

Acknowledgments: Nothing to declare.

Conflict of interests: Nothing to declare.

Funding: Nothing to declare.

Manuscript received at August 31th 2018; Accepted at November 17th 2016

[*]Corresponding author: R. do Bairro da Nossa Sra. da Conceição 22, Covilhã Email: bruno.travassos@ubi.pt