INTRODUCTION

The combat sport named mixed martial arts (MMA) began in the third decade of the 20th century, when Carlos Gracie, one of the founders of "Gracie jiu-jitsu" (also known as Brazilian jiu-jitsu), invited competitors from different combat modalities to participate in the same event with few rules. MMA's fame has increased since 1993, with the first edition of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) in Denver, Colorado (Malanowski & Baima, 2021). Since then, MMA has become one of the fastest growing sports in the world. (Collier et al., 2011), gaining a lot of space in the media (Martin et al., 2015). However, this media advance was not accompanied at the same pace by the scientific support of the training and evaluation methodologies used by MMA athletes (Del Vecchio & Ferreira, 2013; Kirk et al., 2021). A systematic review of MMA was carried out by Bueno et al. (2022) highlighting a lack of studies focusing on technical-tactical aspects and physical fitness in MMA.

MMA requires intense physical effort from its practitioners, as it incorporates different techniques from different modalities, requiring many physical abilities and a need to train the technical, physical and tactical components in the same week (Bounty et al., 2011). This training density, when there is no properly structured planning, can lead to physical and psychological overload of the athlete (Kirk et al., 2021), may increase the risk of injury both during training periods and in competition (Ross et al., 2021). In this way, there is a need to increase scientific knowledge in planning MMA training in order to enhance the athlete's performance and reduce the risk of injury (Andrade et al., 2019), as well as looking for evaluation models that allow identifying the athlete's state of readiness for competitions (Chernozub et al., 2022).

The MMA athlete has peak oxygen consumption values (VO2 peak) from 44.2± 6.7 mLO2/kg/min to 55.5± 7.3 mLO2/kg/min, estimated body fat percentage of 13,4± 5,6%, squat jump and countermovement jump of 51 cm and 45 cm (professionals and amateurs, respectively), long standing jump of 2.19± 0.31 cm, performs an average of 42 repetitions of sit-ups in 30s and 37± 9 repetitions of push-ups in the same duration, maintains an average of 35± 10s on the isometric pull on fixed bar and perform the bench press exercise, on average, with a load of 1.21± 0.18 kg per body mass for professionals and 1.07± 0.20 kg per body mass for amateurs (Andrade et al., 2019; Bueno et al., 2022). However, only the VO2 peak was obtained through a specific test of the MMA, with the remaining indicators of neuromuscular capacity being obtained through indirect tests not specific to the modality (Andrade et al., 2019; Bueno et al., 2022).

There are already validated tests measuring different physical abilities for combat sports, such as judo (Franchini et al., 2009), wrestling (Marković et al., 2021), jiu-jitsu (da Silva Junior et al., 2022), karate (Chaabène et al., 2012) and taekwondo (Tayech et al., 2019), being able, in the case of judo and jiu-jitsu, to differentiate the competitive level of the athletes (da Silva Junior et al., 2022; Franchini et al., 2009). In relation to MMA, until now, the evaluation of athletes’ performance is carried out mostly through non-specific tests (Plush et al., 2021). As far as we know, there is only the test proposed by Paiva and Del Vecchio (2009) named Anaerobic Specific Assessment for Mixed Martial Arts (ASAMMA).

The elaboration of the ASAMMA test was based on the duration of the MMA matches (3 to 5 rounds of five minutes, with a minute interval between them) and the analysis of the execution time of the different techniques used in the combat, conducted through the study of the MMA matches’ dynamics (Del Vecchio et al., 2011). ASAMMA is associated with the aerobic capacity of r= 0.87 and r= 0.60 to aerobic power, both physical abilities measured in generic tests (Andrade et al., 2022). The ASAMMA result variation in amateur athletes between 3.1% and 4.3%. However, there are no studies showing if ASAMMA can distinguish different groups of athletes. Thus, the objective of the present study was to apply the ASAMMA in MMA athletes, and compare their performance according to the competitive level.

METHODS

Type of study and characterisation of variables

The present investigation presents an experimental design (Atkinson & Nevill, 2001). As independent variables, moment (rounds 1, 2 and 3) and competitive level (novice versus advanced) were considered. Physiological parameters (heart rate and blood lactate concentration) and ASAMMA performance parameters (number of strikes) were adopted as dependent variables.

Participants

Male MMA practitioners were involved, aged between 25 and 45 years old, with regular practice (3 times a week in the last 3 months). The sample size was determined using the G-Power software (version 3.1.9.7, Germany), using data from the study by Andrade et al. (2022) as a reference to estimate the required sample size. It was considered that the present study should contain two groups (advanced and novices), and a necessary sample of 10 individuals per group was calculated (5% alpha; 95% beta; statistical power≥ 0.95). Thus, 20 MMA athletes were intentionally recruited (age= 34± 5 years [95%CI 31.8–36.4]; height= 1.77± 0.07 m [95%CI 1.73–1.80]; body mass= 87.2± 16.2 kg [95%CI 80.2–94.3]; BMI= 27.6± 3.3 [95%CI 26.2–29.1]), all of them Brazilians residing in the United Arab Emirates in the period between January and October of 2022.

Procedures

After recruiting participants, visits to data collection sites were previously scheduled. Participants should be in a fed state (between 2 and 4 hours after the last meal), with a night's sleep of 8 hours or more and without high-intensity efforts on the day before data collection.

Two experimental sessions were required for the present study, separated by 24 to 48 hours. In the first session, the study procedures, and possible discomforts that participation could cause were presented. Clarification about the study design and data collection was allowed to the participants. Then, the participants who agreed to participate in the study read and signed an informed consent form. All procedures in this study followed the ethical precepts presented in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Still, in the first session, the participants completed a form with personal data and a standardised questionnaire on the level of competitive performance, in which the athletes are ranked, taking into account a scale from 1 (it represents that the athlete has not practised the sport for more 1 year) until 10, when the athlete has represented the country competitively in this sport (Manning & Pickup, 1998; Manning & Taylor, 2001). Based on the result of the questionnaire regarding competitive level, the participants were allocated into groups (Advanced= 8.5± 2.1 points; Novices= 2.6± 0.2 points; t= 12.24; p< 0.001). In the same session, height (SECA stadiometer, model 213, Deutschland, Germany, with 0.1 cm precision), body mass (EUFY scale, model C1, Changsha, China, with precision of 100 grams), and body fat percentage were measured. For this, a previously calibrated calliper was used (CESCORF®, Porto Alegre, Brazil), and the three-skinfold protocol — pectoral, abdomen and thigh — was used to estimate body density (Jackson & Pollock, 1978). Each skinfold was measured three times by a single evaluator and in a rotation system. After calculating the body density, the Siri equation was Applied to estimate body fat percentage (Siri, 1961).

Finally, in that same session, the participant was positioned in dorsal decubitus, and after 10 min of rest, the heart rate was measured for 5 min (Polar™ heart rate monitor, model H10, Kempele, Finland), and the average value of the period was considered (Schaffarczyk et al., 2022). Blood lactate was also measured at rest from a puncture in the digital pulp, with extraction of 0.8 μL and reading on portable equipment (Lactate Detect TD-4261 lactometer, EcoDiagnostica®, Nova Lima, Brazil).

In the second session, ASAMMA was applied. All participants were in the official uniform allowed for MMA events, consisting of shorts, 4 oz gloves and mouth guard, to increase specificity in relation to a real fight. Initially, the participants had 5 minutes to perform a targeted and modality-specific warm-up with self-selected movements of punches, kicks, dodges and displacements at light to moderate intensity. The evaluation procedure was performed in an environment with controlled temperature (25°C) and humidity (85%) in a space with dimensions of 10 m x 10 m intended for the practice of martial arts, lined with 50 mm EVA™ rubberised plates.

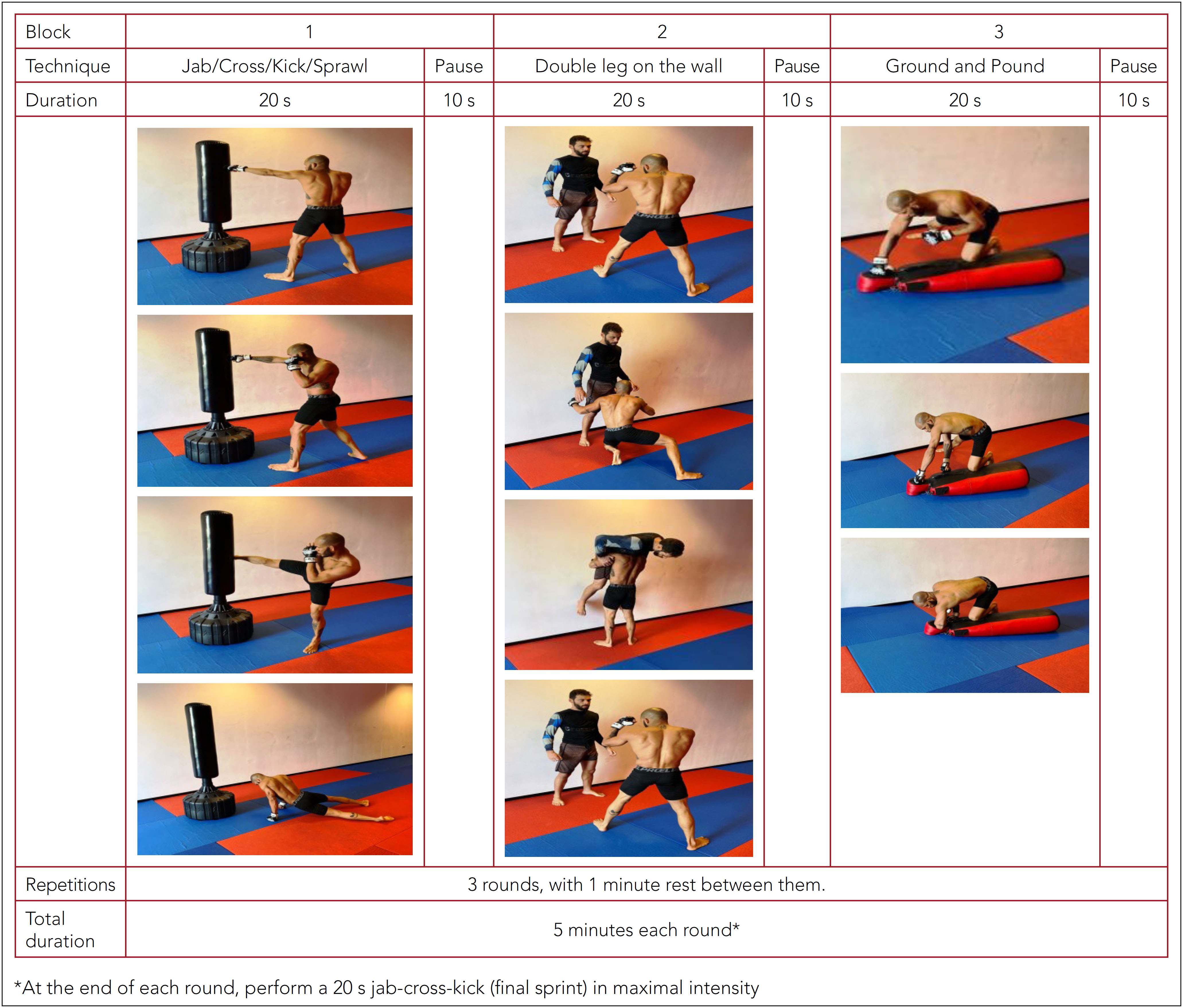

The ASAMMA has a total duration of 1020 seconds (17 minutes), with 600 seconds of total motor actions distributed in 3 rounds with 420 seconds of pause (the pause time includes the interval between rounds). This duration of 600 s is distributed in 3 rounds, with 1 min rest between each. Each round consists of 3 blocks of efforts with specific MMA movements, which are repeated until the end of the total time for each round (movie: https://youtu.be/S7Sn7-ikNN4). Each effort block lasts 20 seconds and is performed at maximal intensity, followed by a 10-second active pause when the participant simulates low-intensity movements. Once the recovery is complete, the participant starts block 2 and so on (Figure 1).

Block 1: interaction

Lasting 20 seconds, the sequence jab/cross/semi-circle kick/sprawl is repeated until the end. For its realisation, a small rubberised training area of 10 m² is necessary, as well as the use of a punching bag for the movements of punches, kicks and sprawl (takedown defence).

Block 2: projection

With a duration of 20 seconds and with the help of a partner, projection movements (double leg) are performed. The training partner remains leaning against the wall, and the subject must remove the training partner from the same weight category from the ground without finishing the projection.

Block 3: ground & pound

A dummy or a punching bag on the ground is used to perform the movement known as Ground and Pound (punches and elbows on the ground level, with the subject evaluated on the dummy). In this block, jab, cross and elbow sequences are performed in the position known as "knee on the belly" for both sides, alternated after executing the three techniques sequentially.

These three blocks are repeated successively within each 5-minute round, and the last 20 s of the round are composed of a sequence (final sprint) of jab, cross and kick in the standing position, completing the 300 seconds, that is, 5 minutes (1 MMA round time). At the end of the 5 min of the first round, the subject recovers for 1 minute and then repeats the process two more times, totalling 3 rounds.

Participants were verbally encouraged at all times to perform as many repetitions as possible while performing ASAMMA, maintaining proper form. In the present study, the individuals wore the heart rate monitor throughout the test to evaluate physiological variables. Thus, the mean heart rate (HR) values (HRMean) were recorded at the end of each round (HRR1, HRR2, HRR3), absolutely (bpm) and relative to the maximum HR (%HRmax) estimated by the Equation 1 (Tanaka et al., 2001):

At the end of each round, blood lactate concentration was also measured.

For the performance data collection during ASAMMA (total sequences of strikes landed per round), a sheet of the scorecard was previously printed and stored in a digital spreadsheet. Due to the importance of knowing the cadence of each round, the fatigue index was also calculated in ASAMMA, and the average of the total number of sequences in round 2 and round 3 was added and divided by 2, then this quotient was divided by the total number of sequences in round 1. In this sense, values up to 0.5 were considered as low resistance to fatigue; values up to 0.8 as moderate resistance to fatigue; and values above 0.8 high resistance to fatigue (Paiva & Del Vecchio, 2009). In general, it is indicated that the advanced athletes performed the three rounds of the standard ASAMMA test. However, for safety reasons, the novice participants performed only one round, composed of 5 min of high-intensity intermittent efforts.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for data analysis. Initially, mean, and respective standard deviations were adopted as measures of centrality and dispersion. Correlation analyses were performed for variables of interest using Pearson's test.

For comparisons between groups (Advanced and Novice), Student's t-test was adopted for independent samples, and the magnitude of the difference was calculated using Cohen's d, which can be classified as small (d= 0.20), medium (d= 0.50) and large (d= 0.8) and very large when d= 1.2 (Sawilowsky, 2009).

In the comparison between rounds for the trained athletes, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) of repeated measures in the moment factor and Bonferroni's post-hoc were applied to locate the differences. In the comparisons between Advanced and Novice, ANOVA was used for repeated measures (moments X groups), using post-hoc Tukey for groups and Bonferroni for moments. Prior to the ANOVA, the Mauchly test was performed to test the sphericity of the data and the Greenhouse-Geiser correction was used when necessary (Maia et al., 2004). The magnitude of differences was presented using eta squared (η²), which can be classified as small (0.1), medium (0.24) or large (0.37) (Cohen, 1988). The significance level was set at 5%.

RESULTS

Data related to the participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. In it, there were no significant differences for age (p= 0.77; d= 0.13), height (p= 0.21; d= 0, 57), body mass (p= 0.74; d= 0.15), lactate (p= 0.91; d= 0.05), HR at rest and maximum HR estimated by age (p= 0.74; d= 0.15). Only the body fat showed a value close to statistical significance (p= 0.056; d= 0.91). Among the anthropometric variables, there was a significant correlation between body mass and body fat percentage (r= 0.65; p= 0.002; Table 2).

Table 1 Descriptive values (mean± SD) of the sample and comparisons by group.

| Advanced (n= 10) | Novice (n= 10) | p-value | Cohen's d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.80 | ± 4.80 | 34.50 | ± 5.81 | 0.77 | 0.13 |

| Height (cm) | 179.40 | ± 9.31 | 174.90 | ± 5.99 | 0.21 | 0.57 |

| Weight (kg) | 88.50 | ± 20.83 | 86.00 | ± 10.68 | 0.74 | 0.15 |

| Body fat (%) | 17.42 | ± 7.47 | 23.97 | ± 6.85 | 0.056 | 0.91 |

| HR maximum (bpm) | 186.30 | ± 4.64 | 185.50 | ± 5.81 | 0.74 | 0.15 |

| HR rest (bpm) | 67.1 | ± 3.51 | 68.7 | ± 3.26 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| Lactate rest (mmol/L) | 2.1 | ± 0.22 | 2.09 | ± 0.15 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

HR: heart rate.

Table 2 Correlation pairs, with respective Pearson's r and significance level.

| Variable 1 | versus | Variable 2 | n# | Pearson's r | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass (kg) | versus | Body fat (%) | 20 | 0.657 | ** | 0.002 |

| Body fat (%) | versus | HR mean (%HR max) | 20 | 0.474 | * | 0.035 |

| Body fat (%) | versus | Sequences of movement R1 | 20 | -0.469 | * | 0.037 |

| Body fat (%) | versus | Sequences of movement R3 | 10 | -0.647 | * | 0.043 |

| Body fat (%) | versus | Fatigue index | 10 | -0.682 | * | 0.030 |

| HR R1 (bpm) | versus | HR R2 (bpm) | 10 | 0.706 | * | 0.023 |

| HR R1 (bpm) | versus | HR R3 (bpm) | 10 | 0.725 | * | 0.018 |

| HR R1 (bpm) | versus | HR mean during test (bpm) | 20 | 0.786 | *** | < 0.001 |

| HR R1 (bpm) | versus | HR mean (%HR max) | 20 | 0.615 | ** | 0.004 |

| HR R2 (bpm) | versus | HR R3 (bpm) | 10 | 0.939 | *** | < 0.001 |

| HR R2 (bpm) | versus | HR mean during test (bpm) | 10 | 0.792 | ** | 0.006 |

| HR R2 (bpm) | versus | HR mean (%HR max) | 10 | 0.811 | ** | 0.004 |

| HR R3 (bpm) | versus | HR mean during test (bpm) | 10 | 0.702 | * | 0.024 |

| HR R3 (bpm) | versus | HR mean (%HR max) | 10 | 0.752 | * | 0.012 |

| HR mean during test (bpm) | versus | HR mean (%HR max) | 20 | 0.840 | *** | < 0.001 |

| HR mean during test (bpm) | versus | Lactate in round 1 | 20 | 0.457 | * | 0.043 |

| HR mean during test (bpm) | versus | Sequences of movements R1 | 20 | -0.538 | * | 0.014 |

| HR mean (%HR max) | versus | Sequences of movements R1 | 20 | -0.601 | ** | 0.005 |

| Lactate R2 | versus | Lactato R3 | 10 | 0.852 | ** | 0.002 |

| Sequences of movements R1 | versus | Sequences of movements R2 | 10 | 0.863 | ** | 0.001 |

| Sequences of movements R1 | versus | Sequences of movements R3 | 10 | 0.855 | ** | 0.002 |

| Sequences of movements R2 | versus | Sequences of movements R3 | 10 | 0.985 | *** | < 0.001 |

| Sequences of movements R2 | versus | Fatigue index | 10 | 0.766 | ** | 0.010 |

| Sequences of movements R3 | versus | Fatigue index | 10 | 0.778 | ** | 0.008 |

#n varied according to the number of athletes observed (only advanced or advanced plus novice);

*p< 0,05,

**p< 0,01,

***p< 0,001;

R1, R2, and R3: rounds 1, 2, and 3; HR: heart rate.

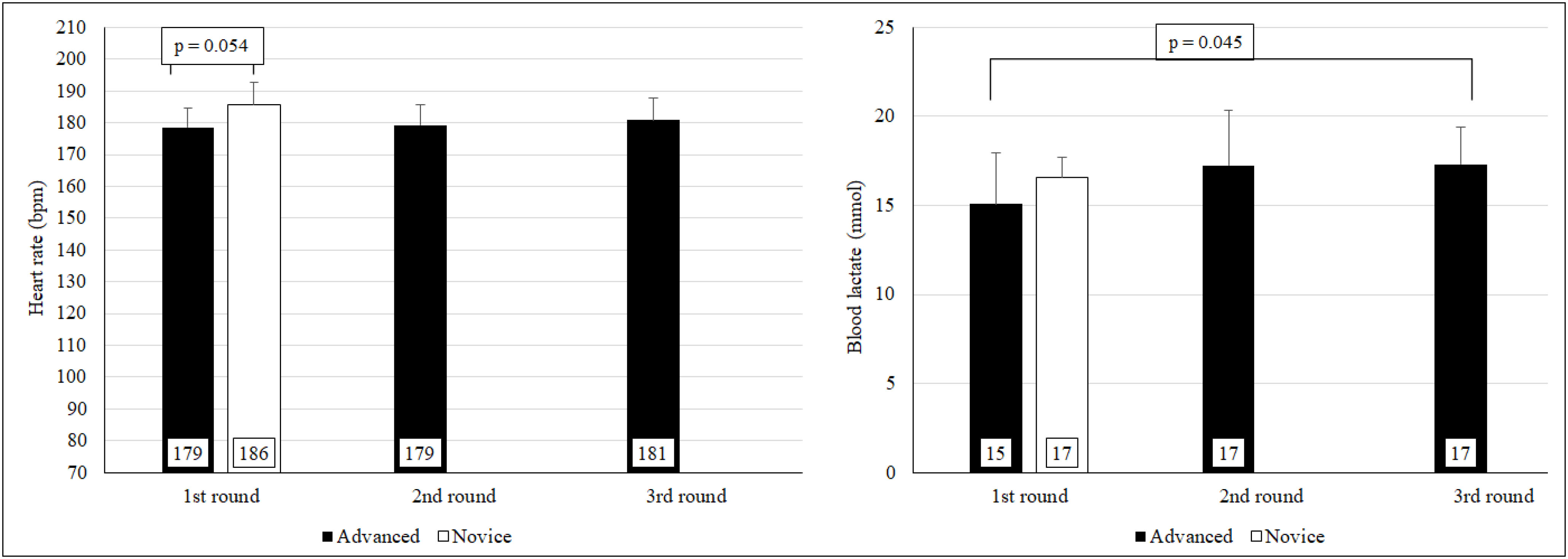

In relation to the heart rate during ASAMMA, it is identified statistically significant differences between groups for HRMean (p< 0.001; d= 2.17), and advanced athletes presented 167± 7, 27 bpm, and novices exhibited 179± 3.8 bpm. The same occurred for values after the first round (p= 0.028; d= 1.07). Regarding the maximum HR percentages, the average HR values in the first round reached 89.2± 11.9% in advanced athletes and 96.3± 3.7% in novices (p< 0.001; d= 2.73). The comparison between rounds was only possible in the group of advanced athletes, given that novice athletes performed only one round (Figure 2, Panel A). Specifically in the advanced group, the analysis of repeated measures of heart rate according to round (rounds 1, 2 and 3) showed no effect for the moment factor (F(2;10)= 1.68; p= 0, 21; η²= 0.16).

Regarding the blood lactate, it is identified that the data after the first round approached the level of significance adopted in the comparison between groups (p= 0.054; d= 0.92) when advanced athletes presented 15.08± 2, 86 mmol/L and novices exhibited 17.15± 1.36 mmol/L. The comparison between rounds was only possible in the group of advanced athletes, given that novice athletes performed only one round (Figure 2, Panel B). Regarding the advanced ones, the analysis of repeated measurements of blood lactate according to round (rounds 1, 2 and 3) showed significant differences between moments (F(2;10)= 5.81; p= 0.0111; η²= 0.39), and the Bonferroni post-hoc identified that the difference is located between rounds 1 and 3 (17.3± 2.08 mmol/L; p= 0.045).

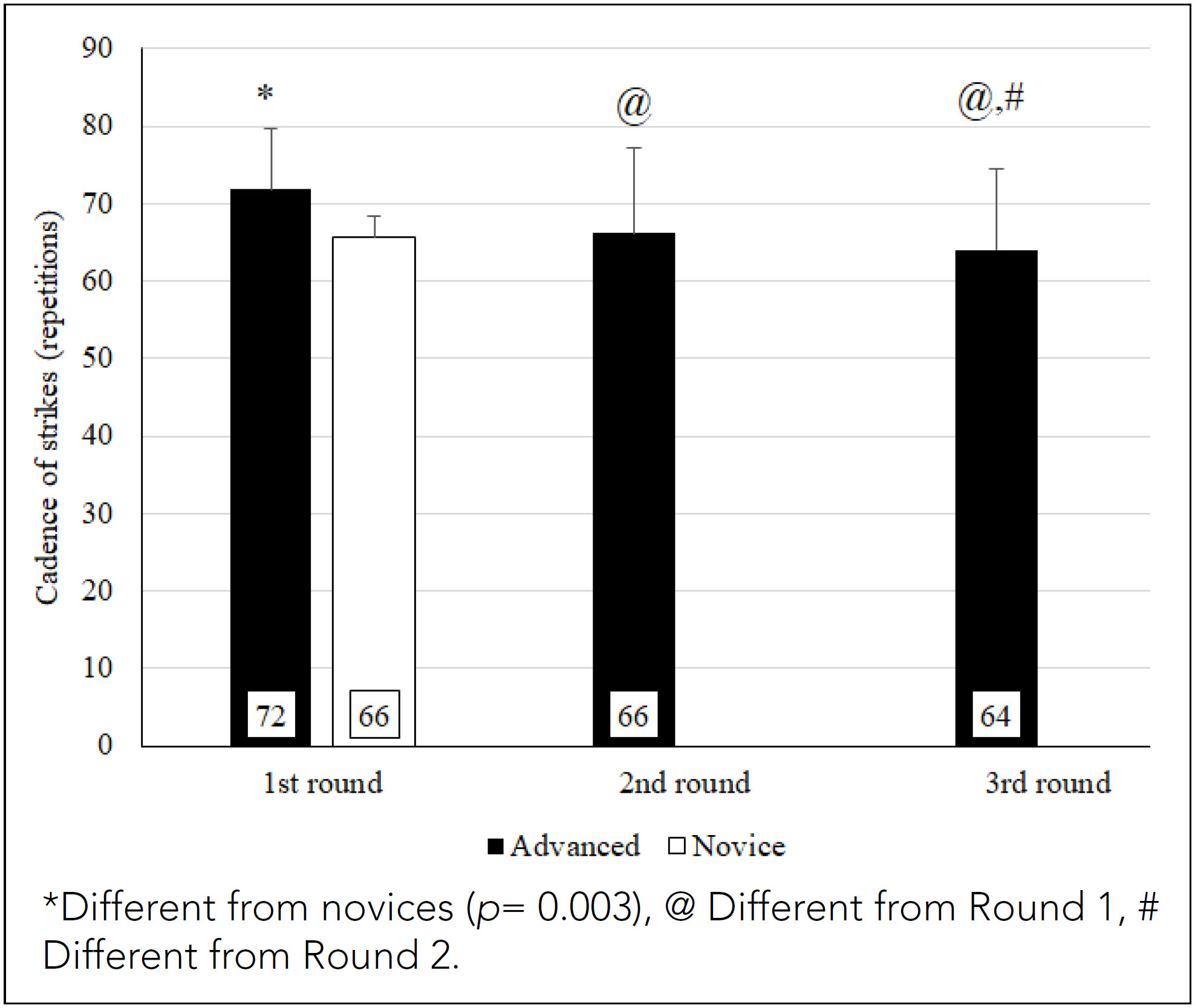

There were differences identified between groups considering the number of sequences of movements performed in the first round of ASAMMA (p= 0.003; d= 1.046), with advanced athletes presenting 71.8± 7.87 strikes and novices exhibiting 65.6± 2.87 strikes. The comparison between rounds was only possible in the first group (Figure 3). In relation to the advanced athletes, the analysis of repeated measurements of cadence of strikes according to round (rounds 1, 2 and 3) showed statistically significant differences between moments (F(2;10)= 14.37; p< 0.001; η²= 0.61), and the Bonferroni post-hoc identified that the differences are located between rounds 1 and 2 (p= 0.04), 1 and 3 (p= 0.005) and 2 and 3 (p= 0.017). Finally, regarding the fatigue index, a performance of 0.90± 0.08 is indicated, and of the 10 advanced athletes, only one presented a score classified as moderate (0.74).

The correlational analyses present significant values between anthropometric, physiological, and physical performance parameters in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the physiological and physical performance responses of advanced and novice practitioners in a specific MMA test. The main findings of the present study indicated that (i) the participants did not differ in terms of age, body composition, HR and resting lactate, (ii) HR at the end of the first round was higher in the novice athletes, (iii) in the advanced group, the lactate values at the end of the third round were higher than the values of the first round and, finally, (iv) among advanced group, the number of sequences of strikes was higher than for novices, decreasing over the rounds.

The evaluation of MMA athletes was widely performed with nonspecific tests of strength, power, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness (Andrade et al., 2019; Bueno et al., 2022; Plush et al., 2021). However, there is a lack of specific tests, as the Anaerobic Specific Assessment for Mixed Martial Arts (ASAMMA), a procedure that was developed considering: i) duration of MMA fights (Bounty et al., 2011), ii) the temporality of the combats in relation to the periods of effort and pause (Miarka et al., 2016; Coswig et al., 2016), and iii) the technical-tactical dynamics, considering the most used techniques (Del Vecchio et al., 2011).

In a recent investigation, Andrade et al. (2022) tested the reproducibility of ASAMMA with 12 amateur fighters and found no significant differences between test and retest, with intraclass correlation coefficients between 0.5 (movement sequences) and 0.9 (rating of perceived exertion). Complementarily, values lower than 5% were observed in the coefficient of variation (CV) for most of the variables measured (between 3.1% and 4.3%), although values close to 10% were identified in the fatigue index. Finally, significant correlations were identified between ASAMMA performance and maximal oxygen consumption in the incremental test (r= 0.67; p< 0.05) and aerobic capacity (r= 0.96; p< 0.05), but the absence of correlations with the Wingate test (30 s), probably due to the duration of the tests (Andrade et al., 2022).

Heart rate is a relevant parameter to evaluate and monitor in combat sports athletes (Slimani et al., 2018). Various tests, such as the Special Judo Fitness Test (Franchini et al., 2009), correlate heart rate with the number of projections, with a lower index in the test revealing better performance. From a physiological point of view, the average HR (absolute and relative) during the first test round was higher in the group of novice athletes, which may be due to better aerobic fitness among advanced fighters (Del Vecchio & Ferreira, 2013), promoting lower cardiorespiratory demand during ASAMMA (Bounty et al., 2011).

Regarding blood lactate, it is indicated that it is associated with the glycolytic demand of physical exertion. In this sense, official or simulated MMA fights present values close to 16 mmol/L (Coswig et al., 2016), values similar to those found in the present study — and which indicate a high demand for the anaerobic component of energy supply (Del Vecchio et al., 2011). Considering that high values of blood lactate can affect muscle contractility mechanisms by interfering with interactions at the level of cross bridges, this could partially explain the loss of performance over the rounds, inferred by the reduction in the number of sequences of movements. However, the present study highlights a high resistance to fatigue in Trained fighters, given that only one presented a moderate index. In this sense, with regard to more successful fighters, it is indicated that memos are more tolerant to lactate (lactic tolerance), as well as a greater buffering capacity of the hydrogen cation in the blood, providing greater muscular resistance (Aschenbach et al., 2000).

Regarding the evaluative and competitive context, sports modalities have been studied regarding several physiological parameters, such as quantification of heart rate and blood lactate concentration. However, the analysis of specific movements is also relevant in order to clarify the physical performance of the competitor, and in the present study, the values were statistically different between Advanced and Novice athletes, evidencing the relevance of this variable in the evaluation routines (Andrade et al., 2019; Andrade et al., 2022).

The present study demonstrates the usefulness of ASAMMA as an evaluation and even training adjustment, given that all subjects showed a significant decrease in the sequence of specific high-intensity movements and concise indicative of fatigue and muscle wasting during the test, in addition to stimulation of the anaerobic energy systems lactic or glycolytic that are considered decisive for the best competitive performance (Del Vecchio et al., 2011). Due to the degree of specificity and physiological demand observed in the present study, the ASAMMA can be used as part of the periodization monitoring of combat modality athletes, as it presents simulations of situations of competitive conditions close to reality (Del Vecchio et al., 2011; Miarka et al., 2016; Coswig et al., 2016).

It is also verified that other modifications can be made according to the opponent and the predominant style of the fighter since the technical and tactical aspects are directly related to the performance and the result of the fight, and recent studies point to technical variation as a fundamental element for unpredictability in high-performance competitions (Miarka et al., 2016).

CONCLUSION

Based on the results obtained, we can conclude that ASAMMA can discriminate between advanced and novice athletes, both from a physiological point of view (using heart rate as an indicator) and from a physical point of view, based on the number of sequences of movements. It is indicated that the model presented in the study presents movement specificity and the relation between effort/pause. Thus, it can be used as an integral part of planning specific training for MMA and serving as a performance evaluation tool to measure the evolution in the development of physical or technical-tactical fitness of MMA athletes.