INTRODUCTION

It is to human behaviour, as an indivisible whole, that we refer when we are discussing sports. This statement, which may be seen as banal, signifies a complete break from overly compartmentalised perspectives (and, as a consequence, with a distorted view of globality) that surround this broad field.

Suppose we are referring to human behaviour, which presents itself in the form of actions/intentions, where various processes may exert influence. In that case, it is not sufficient to analyse only physiological or biomechanical variables in isolation to better understand it (Sérgio, 2005).

By delving into this issue, the coherence necessity legitimises the intention to better understand this problem in its globality, recognising how specific particularities influence the whole (human behaviour) within a specific context (sports activity). This can provide relevant and in-depth knowledge about a wide range of characteristics, capabilities, and human potentialities.

Exploring this issue could contribute not only to a greater understanding of it but, above all, to a different, more comprehensive, suitable, and efficient intervention. An intervention aligned with current knowledge and available tools, which also fosters the development of new mediums for further progress (Almada et al., 2021).

Thus, through sports, understood through Almada et al.’s (2008) definition (the concept exploration could be founded at the Discussion section), we aim to better understand and intervene in the humans’ evolution process, giving a contribution to build perspectives on training and its conception increasingly supported by the available scientific instruments, potentially granting them new meaning and significance, while reinforcing the importance of using sport to serve the process of social development and individual transformation (Almada, 1995; Reis, 2003).

In sports, a privileged medium for the (trans)formation of Man, this issue warrants discussion and clarification, as failure to do so may result in a reductionist framework that not only skews the understanding of the phenomena involved but also hinders ethically acceptable and truly appropriate interventions, considering the inherent complexity of this field (McLean et al., 2024).

Currently, research in the field of sport seems to be moving away from reductionist and deterministic approaches (McLean et al., 2024; O’Sullivan et al., 2021) that focus on very specific aspects (which may indeed influence performance) without recognising the globality, toward focusing on the understanding of the complex and dynamic relationships between the different variables that constitute the relational whole that human behavior represents (Almada et al., 2021; Vicente et al., 2023).

Here, we assume that the behavior we refer to, observable in various forms that may serve as indicators (and thus quantifiable and qualifiable), is merely the “visible” consequence of a set of influential processes and variables that establish relations among themselves, subjected to the constraints and particularities of a given context (Almada et al., 2008; Vicente, 2007).

Thus, understanding the interactions that may constitute the cause(s) of a particular motor output requires analysing the constraints involved and the extent to which their variation influences perceived outcomes (Araújo et al., 2007). We can also affirm, considering complex responsive processes and the ecological dynamics perspective, that sports performance may be seen as an emergent process from the continuous interactions of individuals in a non-linear transformative causality (Pereira et al., 2024).

Specifically considering the variables related to the psychological performance factor (the one that we choose to exemplify our thesis), although we recognise the evolution of the scientific research about this particular topic, we are also aware that the approaches to the problems (and also the intervention on them) related to this particular performance factor is generally made using instruments designed exclusively considering methodologies from the psychology area (Cruz & Viana, 1996), contradicting a systemic and ecological vision that seems to be more appropriate when we are dealing with issues of such high complexity.

That is the main reason why we decided to work with this particular performance factor: the dense complexity involved demands a new vision that fills the gaps of exclusively disciplinary approaches.

The instruments and methodologies normally used to diagnose this type of competencies and skills have many limitations, with assessments typically carried out (if at all) through the observation of expected consequences rather than, for example, through direct measurement (Layton et al., 2023), namely, from the context in which the actions take place (the matches or the training exercises, for example).

In football contexts, although it is common for clubs to ask their coaches for an evaluation of the players, research largely neglects these expert coaches’ and clubs’ perspectives on relevant performance characteristics (Musculus & Lobinger, 2018), as well as the reported difficulties in diagnosing and monitoring psychological skills (Layton et al., 2023).

To change that status, it is important to involve everyone related to the development of sporting human performance, particularly coaches, in an attempt to understand human performance as a whole, and not merely an addition of variables from different origins (a risk that huge specialists’ teams have, if they cannot articulate themselves).

This necessity becomes more acute when, in most practice contexts (especially in youth sports), intervention is the responsibility of a few people and almost exclusively focused on the coach, who must be able to manage the complexity of an infinite number of variables in a profitable way. Coaches’ knowledge about all the performance factors is indispensable, and the notion of the importance of psychological competencies and skills is a determining factor in the success of any intervention concerning this specific domain (Cruz & Viana, 1996), namely, for the holistic development of their practitioners.

Therefore, we affirm that any possible intervention stemming from this medium (especially through training) and the analysis of the behaviours involved (diagnosis/assessment) must be grounded in a solid conceptual foundation (which we attempt to deepen below).

This foundation should enable a deep, comprehensive, and objective understanding of sports activities, as well as the diagnosis of practitioners’ needs, while focusing on the functionality of phenomena - understanding processes, not just outcomes/events. This ensures that, within a dynamic and complex framework, we can manage the specificities of each situation to achieve the most efficient progression.

Given this, the aims of this study are:

A. Assess the opinion of top-level coaches regarding the importance of the psychological factor in the practitioners’ performance;

B. Perceive the opinion of top-level coaches about the possibility of diagnosing psychological skills through the observation of practitioners’ behaviours during training and competition;

C. Understand whether top-level coaches perceive as important the work of psychological competencies through more ecological means (through training tasks, for example);

D. Theoretically ground a conceptual framework that allows a truly holistic diagnosis based on sports activities;

E. Initiate the foundation and structuration of a behavioural analysis matrix for football players, enabling future studies through their capacity to generate trends.

Subsequently, the hypotheses we subject to refutation are:

A. Top-level coaches consider the psychological factor to be decisive in the practitioners’ performance;

B. Top-level coaches believe that it is possible to diagnose skills related to the psychological factor through the observation and analysis of practitioners’ behaviour in training and competition;

C. Top-level coaches believe that the work of psychological skills can also be carried out through the design of training tasks;

D. There is a framework of references that already allows the support of conceptual tools adapted to the holistic characteristics of the sports phenomenon;

E. The construction of a behavioural analysis matrix for football players could be found in the presented conceptual framework and enables future research (derived from its ability to provide important data from observable actions of the players).

METHODOLOGY

Because this is a dense topic where the scarcity of evidence remains a dominant feature, the opinions of those with the most experience and qualifications, as well as those who are most directly involved at the highest levels of performance in this sport, represent an important step in legitimising the relevance of ongoing research.

Therefore, this is an exploratory and descriptive study, with a mixed nature, where we try not only to describe how influential stakeholders (coaches, in this case) particularly interpret the importance of the psychological factor in practitioners’ performance and the necessity of diagnose and train it, but also to constitute a references framework that supports a new vision for the main issue of the sports’ diagnose. Thus, through this specific factor, we may demonstrate the urgency of better research and, consequently, new practices in the sports diagnosis domain.

Participants

Were utilised a non-probability sampling, for convenience, and were applied the following inclusion criteria: Portuguese coaches with UEFA PRO coaching course (the highest level from UEFA), must be working at 2023/2024 season, at least one coach for each of the different contexts to be considered (professional football - 1st and 2nd leagues, professional football - foreign 1st league, senior and youth national teams - men and women), more than 5 years of experience in these contexts.

We excluded coaches from other competitive levels, even if they correspond to the other inclusion criteria. This way, we try to constitute a group of experienced coaches with knowledge about diverse elite competitive contexts. Thus, the resulting sample consists of 10 coaches.

By applying a brief questionnaire to this sample of elite Portuguese coaches (UEFA PRO, n= 10) working in different contexts (1st Portuguese League (n= 2), 2nd Portuguese League (n= 2), foreign 1st League (n= 2), Men’s National Teams (n= 3), and Women’s National Teams (n= 1)), we aimed to understand their opinions and assess their sensitivity regarding both the importance of psychological skills in performance and the possibility of diagnosing them through the observation and analysis of players’ actions in training/matches.

Instruments

The applied questionnaire consists in 5 synthetic questions (4 of them categorical with dicotomic nature and closed answer - yes or no - and 1 of them with an open answer) and was structured by the authors to be specifically used in this study and to capture, in a very simple and direct way (because the access to the individuals who constitutes the sample is very limited), the sensitivity of the coaches regarding the topic to be addressed.

The recommendations of Wilkinson and Birmingham (2003) were used to build this questionnaire. This tool was not previously tested and was built to include a few, but essential, questions based on theoretical assumptions that allow for considering the psychological factor as an influential variable in sporting performance, which can be evaluated by analysing practitioners’ behaviours and developing through training.

The principal aim is to have the possibility to confirm or refute these assumptions based on the empirical experiences of the individuals.

These are the five questions that constitute the questionnaire:

1. In your opinion, is the psychological factor associated with sporting performance crucial to achieving high levels of performance? (Yes/No)

2. Based on your experience and sensitivity, do you think it is possible to evaluate skills related to the psychological factor through observation and analysis of players’ actions in training/game? (Yes/No)

3. If so, can you briefly describe how you carry out this assessment (in which game situations, through which player behaviours/actions, etc.)? (Open answer)

4. Would you consider it useful to use an analysis tool that would allow for initiating a diagnosis of these types of competencies through training/match? (Yes/No)

5. Do you think it would be beneficial to integrate the work of these competencies in training itself, through the exercises that constitute it? (Yes/No)

Procedures

Prior to data collection, all respondents included in the sample were informed of the study’s purposes, and their anonymity was guaranteed, along with the assurance that the collected information would be used solely for this research, after obtaining their consent.

Data were collected during the 2023/2024 football season. All coaches were contacted via email to complete an online questionnaire (through Google Forms) after a first explanatory dialogue was conducted by phone.

All procedures are carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethical Commission of Universidade da Beira Interior, with the process number CE-UBI-Pj-2024-039.

RESULTS

To enhance the consistency of this results we could use the Cochran’s Q Test (appropriate test for analyzing dichotomous responses across multiple related groups) and define: Null Hypothesis (H₀) - The proportions of “Yes” responses are consistent across groups; Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) - There is inconsistency in the proportions of “Yes” responses across groups.

All responses in the tables are “Yes”, so Cochran’s Q test will not detect any variability (since there is none).

Cochran’s Q of freedom: df= 3, p= 1.

The p-value of 1 indicates perfect consistency in the responses across all questions and all coach groups.

This means that all coaches, regardless of their league or team, unanimously agreed on all four questions, suggesting a strong consensus among coaches regarding the importance of psychological factors in sporting performance.

DISCUSSION

Questionnaire results analysis

It is evident that the consensus regarding the first two questions raised (Tables 1 and 2) reinforces what some research suggests about the relationships between personality traits and sports performance, pointing to both direct and indirect links between these two variables (Ruiz-Barquín & García-Naveira, 2013).

Table 1. Coaches’ opinions about the importance of the psychological factor in sporting performance.

| 1- In your opinion, is the psychological factor associated with sporting performance crucial to achieving high levels of performance? | 1st National League Coaches | 2nd National League Coaches | 1st Foreign League Coaches | Men National Team Coaches | Women National Team Coaches | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2. Coaches’ opinions about the possibilities of evaluating psychological competencies through observation and analysis of players’ actions.

| 2- Based on your experience and sensitivity, do you think it’s possible to evaluate skills related to the psychological factor through observation and analysis of players’ actions in training/game? | 1st National League Coaches | 2nd National League Coaches | 1st Foreign League Coaches | Men National Team Coaches | Women National Team Coaches | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Therefore, the open-ended responses obtained to the subsequent question (which aims to assess the coaches’ sensitivity to evaluating competencies related to this performance factor) gain significance: “Can you briefly describe how you carry out this evaluation (in what game situations, through what behaviours/actions of the players, etc.)?”.

From the different answers, a clear inclination towards the use of various qualitative and quantitative indicators collected in practice situations leads us to conclude that coaches, supported by their knowledge and experience, indeed perform diagnostics in this area.

We can note this through statements such as “By the type of decision they make in adverse situations”, “Reaction after actions that are performed. Body language during the game and the different actions”, “Through the identification of a behavioral pattern in competitive-behavioral situations during training”, or “One way is to see how they react to losing the ball or how they respond after making a mistake in a technical action or decision.”.

These statements appear to align with current knowledge of psychological competencies associated with the concept of sports resilience, emphasising the assessment of these observable indicators in adverse situations, such as quickly regaining possession of the ball after a mistake (Ashdown et al., 2024).

Adopting, as would be expected given the complexity involved, a still somewhat vague character, these statements can be extremely rich in guiding the focus towards exploring indicators that seem to be more directly related to assessing these types of competencies. The reference to “adverse situations” and the word “reaction”, the connection to “decision-making,” and the “identification of behavioural patterns” can serve as guides in the research for building instruments that assist us in this task.

Thus, these data become extremely valuable for the foundation of the proposal presented below, which is built around transition moments (characteristic situations in the football game that adhere to many of the terms used by the coaches).

Finally, in order to more specifically understand the utility of research concerning instruments that could assist in diagnosing these types of competencies and subsequent intervention, the following questions were posed: “Would you consider it useful to use an analysis tool that would allow for initiating a diagnosis of these types of competencies through training/match?” and “Do you think it would be beneficial to integrate the work of these competencies in training itself, through the exercises that constitute it?” (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Coaches’ opinions about the utility of a tool that allows diagnosing psychological skills through training/match.

| 4- Would you consider it useful to use an analysis tool that would allow for initiating a diagnosis of these types of competencies through training/match? | 1st National League Coaches | 2nd National League Coaches | 1st Foreign League Coaches | Men National Team Coaches | Women National Team Coaches | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 4. Coaches’ opinions about the benefits of working on psychological competencies through training exercises/tasks.

| 5- Do you think it would be beneficial to integrate the work of these competencies in training itself, through the exercises that constitute it? | 1st National League Coaches | 2nd National League Coaches | 1st Foreign League Coaches | Men National Team Coaches | Women National Team Coaches | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Yes | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Also for these two aspects of potential possibilities, the tendency is unequivocal, reinforcing the importance and utility that research on these subjects can have in the context in which its practical application is intended, steering us away from a mere theoretical exercise with no return.

Although the natural limitations associated with the sample size do not allow for generalisations or comparisons with individuals who work in other important contexts (such as amateur football), we can confirm our expectation about the pertinence of this issue for coaches who directly deal with high-performance development.

If we could expand the sample, other possibilities may arise. This would be a great opportunity to not only understand if it is possible to broaden our conclusions, but also to compare results between coaches with diverse characteristics. Moreover, although differences may appear (namely, between coaches with different qualifications and from different competitive levels, which may influence the importance of evaluating this performance factor), we are strongly convinced that a large majority share the perspective presented here.

However, neglecting the influence of the competitive level (and how the associated pressure could impact the expression of psychological competencies, leading to a different perception of the necessity to address this kind of issue), for example, is an error that we have to avoid, apart from the temptation to misgeneralise our conclusions.

In summary, and reinforcing that future research would benefit from solid theoretical frameworks, since there is a lack of a global theory linking psychological factors to performance in football (Pettersen et al., 2021), we can affirm that we are much more confident that the necessary theoretical framework, which we attempt to outline in this work, is strengthened by the practical insights presented here based on the data collected from this sample of elite coaches.

Concerning some of the hypotheses that we had defined for this work, all the results are aligned to confirm that top-level coaches consider the psychological factor to be decisive in the practitioners’ performance (hypothesis A), believe that it is possible to diagnose competencies/skills related to the psychological factor through the observation and analysis of practitioners’ behavior in training and competition (hypothesis B), and that the work of psychological competencies/skills can also be carried out through the design of training tasks (hypothesis C).

Therefore, based on these results, we found reasons to dig further in order to confirm the other indicated hypotheses (hypotheses D and E), exploring and trying to structure the theoretical support and framework for the collected perceptions, and building the base for a new diagnostic tool.

Conceptualising sport and sports training

Sport is a medium, an instrument for addressing human behaviour, and not only, as some technocrats believe, merely a set of techniques to be taught to athletes to execute functions as efficiently as possible (Almada et al., 1994).

To help define the meaning and significance of this work, this initial statement emphasises the necessity to break away from views of the sports phenomenon that do not fully embrace the notions of globality and complexity required to address the issues related to this field nowadays. Furthermore, because it is essential to acknowledge the evolving nature of society, sports disciplines, and the individuals involved in these activities, given their significant role in their development (Almada et al., 1994), conceptualising the term “sport” is a crucial starting point for understanding the tools employed in this study.

Before introducing the concept of sport that seems most useful to us, considering the phenomena to be addressed, it is essential to retain the idea (with all its implications in this work) that a sport which prioritises the individual, seeking not to produce “just another one like many” but a unique human being, maximizing their abilities and potential, is no longer a futuristic ideal but an urgent need (Vicente, 2007).

Thus, in addition to distancing ourselves from some reductionist views of Man and Sport, opting for a holistic and complex approach to existing phenomena (holistic and complex do not mean lacking details) and in line with the founding principles of Human Kinetics Science, we also highlight the existing possibilities in this field nowadays using the available resources.

Moving away from formality and towards functionality, we believe in a sport defined as follows: In the interaction between Man and context, mutual adaptation phenomena are constantly established. When this dialectical relationship is based on kinesthesia, and Mans’ training is crucial, we are engaging in a sports activity (Almada et al., 2018).

As a result, it is important to note that this particular interaction consists in sequences of stimuli - aggressions, reactions, adaptations, and transformations - that are carried out through certain active principles of the proposed activities (which will, naturally, have their secondary effects), acting on human homeostasis allowing diagnoses and the subsequent prescriptions and assessments (Almada et al., 2018).

Many positions have been taken on what sport and sports training should be, particularly football training, since the advent of modern team sports during the Industrial Revolution. Consider, for instance, the numerous seminars, conferences, and publications on this topic that continue to emerge.

Building the future of Man from the present requires using tools (both material and conceptual) that respond to the main characteristics of the species and the planet (constantly changing). This involves framing and adapting, considering the recognised complexity and dynamics, rather than excluding or standardising. Hence, the chosen concept of sport is justified by its functional aspects, which allow for the necessary flexibility to address issues that arise from this specific interaction.

In conclusion, we assert, based not only on the above sentence but also on previous references, that football can be an essential tool for human development, with unique characteristics and conditions (such as generating immense interest and emotion) to play a prominent role in society, having been shaped over time by the existing needs and knowledge.

It is clear that all conceptual choices influence the course of the knowledge-building process. As a result of the references here employed, and to define sports training with the coherence and functionality necessary to continue the research, we propose the interpretation of this concept as an intentional continuum of varied stimuli that promote reactions, adaptations and transformations (based on kinesthesia) that obligates a concern (and, thus, preparation, planning, and programming) with Mans’ training, contributing to their happiness (drawing a somewhat controversial parallel between this concept and the shared pursuit of transcendence that emerges from Human Kinetics Science) within accepted ethical boundaries.

Thus, we believe we have aligned the conceptualization of sports training with the other necessary definitions for the solid foundation of this work, opening possibilities for addressing problems related to this area that a definition like a complex process aimed to develop, according to a plan, a certain state of sports performance and demonstrating it in competitive situations (Cunha, 2016) would not provide.

A systematics of sports activities: team sports

If functionality is a principle and common denominator in the conceptual definition involving this work, it must also be applied to the use of a taxonomy of sports activities. Football, being a predominantly team sport, according to Almada’s proposed taxonomy (Almada et al., 2008), presents various particularities, of which we highlight two main variables to consider: group dynamics and task division. We can also outline some unique aspects that this team sport can facilitate: Formational Character - due to the influences and educational effects of the game; Educational Value - through the positive and multifaceted action on the personality of athletes; Positive Influence on Physical Development; Development of Team Spirit; Development of Organization and Discipline, nurtured by the acceptance of game rules, refereeing, and discipline; Development of Initiative; Development of Practical Thinking (Almada et al., 1994).

All these statements require special attention, as it is necessary to verify the extent to which these factors may be manifested as intended. However, they perfectly illustrate the role that football can play in human development.

The main characteristics of football are: the existence of a game object (ball); complex competition (individual/collective); unitary game rules; limitation of game duration (time); mandatory presence of refereeing; standardization of game inventory and playing field dimensions, within certain limits; and the existence of specific techniques and tactics (Almada et al., 1994).

These are all formal aspects of this sport that exert a significant influence on how the game is played and provide the specificities that characterise football.

However, to better understand how it is possible to analyse this activity, it is necessary to comprehend the model proposed by Almada et al. (2008) in its simplified form: t≥ t’, where t represents the time of offensive action, and t’ represents the time of

On the other hand, a sports activity is not just a set of gestures. Therefore, we can replace t with the sum of a multiplicity of times - t1 + t2 + t3 + tn - where each of these times translates aspects to consider in training for that specific situation and, thus, allows the calculation of possible gains, the contributions that can enhance efficiency and, consequently, defines the value of the investment that justifies planning for the best possible performance (Almada et al., 2008).

Finally, despite all the arguments presented, it is essential to remember that a model is an instrument that, by representing reality from a specific perspective, enables the understanding of certain aspects, the dialectical interconnections, and the relationships between those aspects. The main objective is not to explain reality as true or assume the results of some trials as valid for all phenomena, but rather to serve as a medium to understand some aspects (without forgetting that each part must represent the dynamics of the whole) of reality, taking into account its complexity (Vicente et al., 2013).

Challenges to diagnosis in a complex scenario

The assessment of competencies/skills in children, youth and adults is a topic of significant study interest in itself. However, it becomes particularly intriguing when the proposal is to carry out these tasks through sports practice.

Today, it is not uncommon to propose that sports can serve this purpose, and, taking these ideas further, to advocate that any potential impact can be applied to various life contexts. Nevertheless, we find that knowledge about the real and rigorous reliability of the instruments used in this field to fulfil the above-mentioned goal is still limited.

We believe that, by addressing this issue using a reference framework grounded in the complexity concept inherent to these phenomena, we can seek answers that distance us from the usual “guesswork” and perhaps yield more valuable insights into the related questions.

Thus, by taking advantage of the potential gap revealed by research in this area, the formulation of the hypothesis presented here appears as a pathway to explore in the development and operationalisation of a truly holistic perspective on assessment and intervention in sports. It could also signify the opening of a path toward new research in this area, which seems to have stagnated, just like our society, in certain concepts of Sport, Education, and Health that have already exhausted (although many still refuse to accept) their positive outcomes.

Sport, like other areas of Society, despite the enormous advancements made in recent decades - such as the introduction of increasingly advanced technology in various contexts related to practice - will likely continue along the path of increasing data collection capabilities, information processing and precision of the interventions made (consider the possibilities offered by GPS for training monitoring in football, for instance).

However, despite this avalanche of progress, the inadequacy of theoretical positions with Cartesian and positivist overtones, or simply a lack of understanding of the characteristics inherent to this phenomenon, renders certain solutions futile or less effective, no matter how modern or well-supported they may appear.

Therefore, beginning to inquire about the role that Sport (and which Sport) will assume in the future Society is, regardless of the complexity faced in envisioning answers, a necessary exercise to subsequently construct a body of work endowed with the worldview required in this field.

Numerous authors, from Toffler to Morin, alert us to the changes that the world has undergone (and those that are yet to occur), changes that promote transformations in people, impacting how they perceive interpersonal relationships, the interpretation of work obligations, nutrition, and healthcare, among others. If we wish to delve deeper into the analysis, we can also consider their concept of Education and the perspectives related to it.

Trends seem to be pushing us towards a greater need for people and organisations capable of adapting to new contexts, with the flexibility to mobilise different types of resources efficiently and obtain tailored responses to problems that emerge at an increasingly rapid pace. In this regard, Sports, primarily viewed as a medium for the (trans)formation of individuals, should help pave the way towards new solutions that allow us to respond to all these challenges as effectively as possible.

All of this necessitates the construction of diagnostic instruments that facilitate the formulation of hypotheses that do not present themselves as certainties (highlighting the notion of framing within an open and dynamic system but also the need for confirmation/refutation) but, otherwise, enable the search for causes in the dialectical relationships established between different performance factors.

Naturally, they should be framed within a reference context that accommodates contributions from different areas of knowledge, while considering the characteristics of the phenomenon being handled and the inherent limitations of any medium considered for understanding it.

Considering the necessity to develop a validated instrument for the observation and analysis of this behavioral information that also serves as a measure of the intervention efficacy (Musculus & Lobinger, 2018), this study could be assumed as being ambitious, touching upon different areas of knowledge (which may cause discomfort) without denying the origin that aims to ensure comprehensiveness: the performance of players in the game.

If we could prove that this is a functional and profitable possibility, testing the validity of the builded tools for certain contexts, maybe we could force a step into a new vision for performance development.

The individuals’ behaviours in training/game, given their centrality in this matter, are the main motive that must bring together all the specialists surrounding sporting performance. Naturally, this assumption would have impact in structuring technical teams, in the definition of roles and contributions of each member and, mostly, in the used diagnose and intervention methodologies.

In this work we are trying to defend that a diagnose based in the assessment of individual actions in training/game, which may cross technical-tactical data, internal and external load data, and psychological data (non-neglecting none performance factor in a constant confirmation-refutation process of searching causes), necessarily needs, as a consequence, a global and integrated intervention (focused, again, on the individual actions in training/game contexts and how we could achieve the desired evolution in behavior).

This approach appears to be aligned with a co-evolving design practice, which requires ascertaining the relevant informational variables at any given moment for each performer or team (Araújo et al., 2021). Manipulating the individual, task and environment variables in a specific way, and considering all the performance factors and the particular goals for each one, we could structure, diagnose and intervention tools that help us to really understand the players in all their extension.

The diagnosis through sports activities: for a specific diagnosis definition

Following the discussion above, building a tool that allows a diagnosis through sports activities is of utmost importance to provide practitioners with individualised interventions (considering their characteristics, potential, and objectives) and with profitability (in managing costs/benefits).

How can we know the characteristics, assess the capacities, and identify the potential of each practitioner? The diagnosis, as we advocate, it is a tool in which we do not seek everything, nor measure everything, but rather search for what is necessary, continuously weighing the costs and benefits of situations, the performance and which variables or indicators are necessary and may allow us to achieve the best diagnosis of individuals in sports activities (Vicente, 2005).

Based on these assumptions, to achieve the proposed objectives with positive performance, it is essential to define what we want and can observe and work on with each proposed activity. Naturally, we do not start from scratch (since the context, task, and individuals create unique circumstances), so it is a priority to define and justify the behaviours we aim to predominantly elicit through the proposed activities. These behaviours will provide a foundation to define goals and assess which variables we need to intervene in to achieve those goals (always with a performance perspective).

But when to diagnose and when to intervene? The answer we have to this question is: whenever possible and necessary.

The analysis of performance, both individual and collective, is an area with exponential influence in the sports phenomenon. It can be stated that game analysis is currently regarded by specialists as an indispensable and fundamental part of the preparation process for team sports games, as well as a vital process for providing feedback during training and games/competitions. Thus, both the observation and analysis of the game of one’s team and of the opponent are of great relevance in preparing teams and players (Travassos & Malta, 2014).

In our opinion, all activities (properly constructed and with a defined intent) allow for a diagnosis, as they enable the coach to perceive information that can subsequently be used in constructing interventions aimed at improving the performance of practitioners/teams. Moreover, constant diagnosis will contribute to maximising a resource that many may think is virtually infinite and low-cost, but which, in reality, is not - time.

For diagnosis to yield better results, it is necessary to understand not only the individual and the activity they practice, but also the dialectical relation established between the two entities.

In consequence, it is possible to systematise three major groups of problems that, from a functional perspective, correspond to adaptive processes: mastery of oneself, of the territory, and social relationships (Vicente, 2005).

Thus, we believe it is possible to deduce and frame causes in the different constitutive domains of the global picture represented by the practitioner in the activity, prioritising the analysis of behaviours and accepting motor gestures/actions as indicators of those same behaviours, moving away from performance analysis perspectives that evaluate “the gesture by the gesture”.

This behavioural analysis through gestures/actions is possible if we view the gesture as the visible consequence of a global and holistic process that is the individual (Vicente, 2005), without defining gestural patterns for later comparison and evaluation of practitioners. In this regard, it is worth emphasising that the pursuit of ideal execution models can result in training prescriptions that are misaligned with the players’ characteristics, causing significant fluctuations in their performances (Passos et al., 2006).

By approaching motor gestures/actions in this manner - as consequences of a continuous process - it becomes important to consider what may precede and/or originate them, providing insight into the individual at sports practice.

As a result, it is crucial to introduce the concepts of Sensory Inputs, central processing, and Motor Outputs, the latter concept referring to the “gesture” mentioned earlier, which is the visible part of behaviour. Focusing solely on Motor Outputs disregards the cause of their emergence, ultimately neglecting the individuality that leads each person to materialise in actions what they perceive, feel, and think. If we confine ourselves to the “visible” aspect, the gestures, we are ignoring the most important element: the cause of those gestures (Vicente, 2005).

Therefore, for the diagnosis we wish to carry out, it is essential to analyse capacities and potential at the levels of Sensory Inputs, Central Processing, and Motor Outputs, relating them to the individual functions’ performance and the objectives to be met. These will influence the relation between diagnosis, prescription, and evaluation, which are necessary to enhance the training process of each individual (Vicente, 2007).

It would be useful if it allows us to identify the main variables that need to be controlled and their indicators, enabling us to recognise the problems that should be addressed and to identify the capacities and potential of the players we will work with (Vicente, 2007).

However, it is essential to understand that a functional comprehension of phenomena enables us to grasp what lies behind a specific consequence, allowing us to interpret indicators effectively and understand their significance (Vicente, 2007).

The work would be much easier if we assumed that all individuals react the same way to the same stimuli, and it would also be simpler to assert that identical problems in different individuals have the same causes or consequences; however, we firmly recognise the inadequacy of these axioms.

The belief in diagnosis as a tool to be utilised in the first step of managing sports activities, along with the assertion that it should be conducted consistently, necessitates that the planning and programming of any training activity (prescription) be approached openly and dynamically, allowing for adjustments that may prove necessary at any moment, according to what is deemed profitable.

As explained earlier, the behaviours to be predominantly elicited in the activities will form the foundation for initiating this cycle, which begins with diagnosis and is reflected in the unfolding of the entire process, including intervention and evaluation. Diagnosis is not an end, but a way (a process) to identify the starting point for the continuation of the training process (Vicente, 2007).

For all these reasons, we believe that a well-adjusted intervention can enhance an individual’s evolution through a specific activity, and this intervention can only be as effective as the diagnosis from which it originated. As the more accurately the main causes of a problem are identified, the more direct and profitable the intervention can be (getting “straight to the point,” avoiding resource waste).

Since diagnosis is a tool that allows us to better understand individuals, prescriptions and training exercises can no longer ignore individuality, the characteristics and particularities of each practitioner, and the importance of considering these aspects in defining development strategies (Vicente, 2007).

Thus, the prescription should not be made based on predefined standards or rules, moreover, it should not be approached as applying the same measures to everyone. Base the diagnosis on gestural standards would inevitably lead to prescriptions to lean toward the “perfect gesture”, but by using the behaviors to be predominantly elicited as our basis, the prescription aims for education/training through the use of models that allows the understanding of the functionality, enabling us to achieve the most profitable and better functional balances adapted to the individual, to their individuality as a person, and not to the majority of people or average values (Vicente, 2005).

In this way, we clearly emphasise the importance of designing prescriptions according to what is diagnosed, highlighting the relationship established therein. And, as we argue that diagnosis is an ongoing process (the notions of non-finitude and also non-linearity are fundamental), the evaluation exercised over the proposed prescription is also of utmost importance, allowing us to know whether the evolution is occurring in the desired direction and in the appropriate manner.

After all that has been presented, and considering these three tools (diagnosis - prescription - evaluation) as fundamental and inseparable for a methodology that contributes to better human development through sports activities, what we seek to justify and operationalise in this work is a globalizing view of diagnose through the analysis of behaviors/actions in football.

Starting by identifying trends at specific moments in the football game that allow us not only to characterise it collectively and individually (at technical-tactical level) but also to cross this data with other information that, analysing their relations and influences, offers us the possibility to understand causes and know deeply the individuals involved in the game.

An instrument for diagnosis through football

If we agree that skills such as decision-making in high variability and complexity contexts, or the ability to assume leadership roles within a group, are important for practitioners of team sports, and even for individuals who may work in future organizations (or simply live in the world of the future - which has already begun today!), we must necessarily agree that it is not only beneficial bu t essential to educate/train these types of competencies/skills with them.

Sport, with its wide range of activities, is an area that enables or promotes processes that allow this to happen. How? To what extent? At what costs and with what kind of benefits?

Delving deeper into these questions, we can also ask:

In football, particularly, by observing technical-tactical behaviours (actions in training/match), do we have any possibility of deducing capabilities/skills in the various factors (psychological, for example) that influence performance?

From the observable part of behaviour, what deductions can we make to at least begin diagnosing characteristics, capabilities, and potentials?

Currently, we have numerous instruments to measure with precision and rigour, both in training and matches, and through observation and analysis. For example, these include parameters associated with a player’s physical factors (GPS, heart rate monitors, etc.), their technical-tactical performance, and the actual results of their performance.

However, we cannot yet make the same assertion regarding psychological competencies/skills associated with performance. The attempt to sum up the parts does not contradict the necessity of considering the dialectical relationships established between the different performance factors, each with its own predominance, in all situations experienced by the players.

Suppose we assume equal importance of all the performance factors (which requires us not to neglect any) and also the expression of them all in observable actions during training/match (because human behaviour is a representation of globality). In that case, we need to accept, for the sake of consistency, that in these observable actions we have the manifestation of the capabilities/skills of the different factors, which will naturally be associated with certain measurable indicators and can, thus, be used to better understand the players in this particular context.

Sport, our foundational area of study and research, instead of “opening” up the human to see what is happening inside, seeks to interpret the phenomena that occur, even within the human, through the effects obtained (Almada et al., 2022).

Disentangling these indicators, their causes and their meanings is, as it could not be otherwise, tremendously complex (but it is at this level that we need to position our analysis). Therefore, creating simplified models of analysis with an undeniable connection to the vision that supports the overall understanding of the game is a path that can allow us to perceive valuable information during the intervention phase.

To accomplish this work, backed by the simplified model of analysis of team sports (t≥ t’) proposed by Almada et al. (2008), we builded an analysis grid for the transition moments from defense to attack, and from attack to defense in football, aiming to understand the eventual possibility of identifying individual trends that, by knowing the main variables involved (of the individual, the task, and the context), allow us to deduce issues and, subsequently, structure intervention situations to test causalities at the level of the different influential domains on the player (the domain of oneself, the territory, and social relations).

For a systemic understanding of football, it should encompass three fundamental and intrinsically related aspects: phases, stages, and moments (Castelo, 2014). The assumptions underlying these definitions have a distinctly formal character (such as having or not having the ball, or the location of the ball, etc.), which in certain situations makes the analysis of dynamic, continuous, and complex phenomena-such as those that characterise team sports-quite ambiguous.

However, without losing sight of the dialectical relations established between different identifiable formal patterns in the game, it seems to us that these concepts can be useful in understanding distinct sets of issues.

Thus, keeping in mind the notion of the required globality, we chose to focus the analysis conducted in this work on the moments of the football game (defense-to-attack and attack-to-defense transitions), which rely on the basis of: (i) a mental predisposition (strong attitude) of the players transitioning: (i) from defense to attack or from attack to defense; through the (ii) permanent offensive vision of the game, through which one attacks the ball, either to regain possession or, when in possession, to attack the opponent’s goal with the intent to score (Castelo, 2018).

These moments, and their effectiveness, can take on different forms, namely: (i) rapid, in the sense of directing the ball towards the opponent’s goal (in attack) or reacting immediately to a loss of possession (in defense); (ii) immediate, manifested by the reaction of all team players immediately after regaining possession of the ball (in attack) or by pressing the player in possession of the ball and all those better positioned (in defense); (iii) secure, through maximizing actions that avoid the premature loss of the ball (in attack) or by actions to time the opponent’s attack (in defense); (iv) adapted, in line with a correct evaluation of the opponent’s defensive or offensive organization levels (Castelo, 2018).

This choice, necessary for us to have not only support for the application of a sufficiently robust experimental protocol, but also to enable us to deal with a less comprehensive set of information that allows us to draw well-founded conclusions within the available time frame, arises from the perception that many of the observable actions in these situations may be related to behaviors already identified as being associated with certain psychological competencies (namely, those related to the concept of resilience in sports) (Ashdown et al., 2024).

Resilience is a psychological construct that, despite not having a single, consensual definition in the Psychology field, can be defined as the ability of people to overcome adverse/stressful situations and emerge stronger from them. This has gained a lot of importance in the sporting context in recent years (Ortega & Montero, 2021).

Furthermore, concerning the study of transitions, the number of studies developed in this area is scarce, representing a gap given its importance in modern football (Travassos & Malta, 2014).

Although this is a topic steeped in immense complexity and with little associated research, particularly concerning football, 36 players’ resilience behaviours have been identified, grouped into 14 categories and six themes (Ashdown et al., 2024), which we believe can emerge from the transition moments if we consider them as a stressor associated with the game.

The themes listed in this study are: (a) resilience behaviors focused on support from teammates, (b) resilience behaviors focused on emotion, (c) resilience behaviors focused on effort, (d) resilience behaviors of recovery, (e) resilience behaviors associated with robustness, and (f) resilience behaviors focused on learning (Ashdown et al., 2024).

However, by exploring some of these themes more deeply and, above all, the behaviors framed within them, we notice the potential alignment with the technical-tactical action analysis matrix constructed, serving as examples such as: “High physical effort to quickly regain possession of the ball after a mistake” or “Immediate positive reaction to a mistake (for example, pressing)” (Ashdown et al., 2024).

Using time as the main indicator of analysis and knowing, by definition, the narrow margin that transition moments offer us for this (male noun; 1. A very short period of time. 2. A particular time or occasion. “moment,” in Cambridge Dictionary [online]), building a qualitative and quantitative analysis matrix of characteristic actions of these moments (which, naturally, could be translated into distinct temporal relations) can help us detect trends that raise hypotheses/issues to be tested (the principle of diagnosis).

In future investigations, if the principles behind this tool prove to be adaptable, it will be important to test the eventual adjustments that should be made to achieve profitability in diverse contexts (e.g., different age groups, genders, etc.), keeping in mind that different characteristics may represent different temporal intervals to consider.

Analysis matrix for transition moments in football

The operational proposal presented here is structured around a simplified categorisation of two sets of actions: one pertaining to defence-to-attack transitions (DAT) and the other to attack-to-defence transitions (ADT).

These actions are interpreted as relevant for addressing emerging game issues during transition moments, allowing the assessment not only of the frequency with which they occur but also of the associated success, as well as translating their occurrence into different temporal dimensions.

First, in an attempt to delineate possible interpretations for detecting transition moments in the game (concept supported by the theoretical framework presented above), it was defined that “In situations of duels/disputes, possession is considered to change (indicating DAT/ADT) when the result of the duel benefits the team that initially did not have the ball (with the 2 seconds after the dispute used as a temporal reference and 1 successful pass following the dispute as action reference). Situations where the ball goes out are excluded.”.

This definition was structured based on the idea that these moments of the game happen when the ball possession changes between phases (offensive and defensive) (Castelo, 2018), resulting in specific collective and individual behaviours.

This way, the intention is to define a pattern through easily observable and measurable indicators that allows a relatively straightforward distinction of moments that can or cannot be included in the analysis, despite potential discussions regarding the used criteria.

From this, results the following analysis matrix, with two sets of actions identified (Table 5).

Table 5. Set of actions in the analysis matrix related to the Defence-Attack Transition (DAT) and to the Attack-Defence (ADT) moments.

| DAT | ADT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action Beginning | Ball Conduction | Pass | Shot | Action Beginning | Result | Intention | ||

| Direction | Result | Direction | Result | Result | ||||

To begin the detailed analysis of each of these sets, and based on how the time variable can unfold into actions during these game moments, the “Action Beginning” of the player was identified as the first reference point for analysis.

Two types of actions regarding DAT were categorised: “Before the opponent’s first touch” and “After the opponent’s first touch.” (Table 6).

Table 6. Division of the “Action Beginning” indicator in the analysis of the Defence-Attack Transition (DAT) moment.

| DAT |

|---|

| Action Beginning: |

| Before the opponent’s first touch |

| After the opponent’s first touch |

For ADT, three types of actions were identified: “Did not initiate action,” “Less than 1 second after the last touch,” and “More than 1 second after the last touch.” (Table 7).

Table 7. Division of the “Action Beginning” indicator in the analysis of the Attack-Defence Transition (ADT) moment.

| Action Beginning: |

|---|

| No action initiated |

| Less than 1’’ after the last touch |

| More than 1’’ after the last touch |

These indicators, structured around the embodiment of the time variable (knowing that e= v.t), enable differentiation of players’ tendencies during critical moments in the game, where the time associated with their definition inherently highlights the urgency for speed in players’ actions.

Although the speed associated with the action beginning is considered a critical factor in these moments, from our perspective, it alone does not provide sufficient information to better characterise the game and the players.

Therefore, it is necessary to cross-reference indicators related to the success/failure of the different possible sequential actions. Hence, the categorisation, in both moments, of the actions predominantly utilised (related to individual technical-tactical actions) as well as their outcomes or even the intentions revealed. Let us examine Tables 8 and 9 with the respective categorisations.

Table 8. Indicators division in the analysis of the Defence-Attack Transition moments.

| DAT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball Dribbling | Pass | Shot | ||

| Direction: | Outcome: | Direction: | Outcome: | Outcome: |

| BD Own Goal | Shot | P Own Goal | Teammate | Goal |

| BD Opponent’s Goal | Pass | P Opponent’s Goal | P Intercepted | On Goal |

| BD Lateral | Lost | P Lateral | P Out | Shot Blocked |

| Suffered Fault | R Fora | |||

Table 9. Indicators division in the analysis of the Attack-Defence Transition moments.

| ADT | |

|---|---|

| Outcome: | Intention: |

| Did Not Intercept | Maintained Recovery Intentions after 3 Opponent Touches |

| Intercepted/Recovered the Ball (maintaining possession) within 3 Touches of the Opponent | Slowed Down or Nullified Recovery Intent after 3 Opponent Touches |

| Intercepted/Recovered the Ball (maintaining possession) after 3 Touches of the Opponent | |

| Fouled | |

For the DAT, the individual technical-tactical actions of “Ball Dribbling”, “Pass”, and “Shot” were assumed to best encompass the range of motor skills utilised during these transition moments. This allows assessing not only the frequency of each action but also the associated success (in the “Outcome” category).

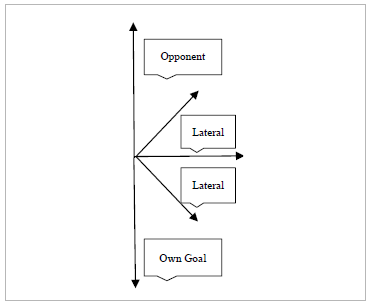

On the other hand, to differentiate the types of decisions that characterise a given player and the success of their decision-making, it was deemed relevant and important to categorise the “Direction” in which the game is intended or can be directed following the DAT. Three possibilities were defined for “Ball Dribbling” and “Pass”: “BD/P Own Goal” when the ball is predominantly directed towards the goal that the player’s team is defending; “BD/P Opponent’s Goal” when the ball is predominantly directed towards the goal that the player’s team is attacking; and “BD/P Lateral” when the ball is predominantly directed towards areas close to the sideline of the field.

About the “Direction” indicators, it is important to note that it is the first action of the player who recovers the ball that is considered. Furthermore, since we have established three options (own goal, lateral, and opponents’ goal), it is necessary to define clearly how to choose one over the other on different occasions. The image below (Figure 1), using x and y axes on the field, represents our reference to solve this issue (considering 90º and 45º angles to simplify the decision).

Regarding “Shot”, four possibilities were considered: “Goal” when the player who recovers the ball shoots following the recovery and scores in the opponent’s goal; “On Goal” when the player who recovers the ball shoots following the recovery and, although not scoring, the ball is saved by the goalkeeper or hits the posts; “Shot Blocked” when the player who recovers the ball shoots following the recovery and the shot is intercepted by a defender or teammate; “Shot Out” when the player who recovers the ball shoots following the recovery and the shot goes directly out of bounds (without touching any elements in play).

Thus, it seems possible to gather sufficient information from the game through clear indicators that allow us not only to identify collective patterns but also individual trends that we can use to conjecture hypotheses and initiate a more extensive diagnosis in search of the causes of certain actions (which we must take care to properly contextualise).

Regarding the ADT, considering that regaining ball possession becomes the primary objective, both collectively and individually, the “Outcome” of the actions carried out following this moment was chosen as indicator, delineating four possibilities: “Did Not Intercept” when the player who loses ball possession cannot intercept or recover it; “Intercepted/Recovered the Ball (maintaining possession) within 3 Touches of the Opponent” when the player who loses ball possession manages to intercept or recover it before the opposing team makes 3 touches on the ball; “Intercepted/Recovered the Ball (maintaining possession) after 3 Touches of the Opponent” when the player who loses ball possession manages to intercept or recover it after the opposing team makes 3 touches on the ball; “Fouled” when the player who loses ball possession commits a foul on the opponent.

Thus, beyond the success or failure of the actions taken during the transition, we can gather information (using limits, such as the number of touches, to define the indicators) regarding the variation in the time interval during which each player tends to act.

Additionally, extending the analysis in time (beyond the 3 touches of the opponent) to better understand the players’ attitudes towards all the interactions generated during the ADT moment, it became necessary to collect data about their “Intention” over time, defining two options: “Maintained Recovery Intentions after 3 Opponent Touches” when the player who loses ball possession remains committed to fulfilling their defensive duties; “Slowed Down or Nullified Recovery Intent after 3 Opponent Touches” when the player who loses ball possession ceases to fulfill their defensive duties or reduces the speed at which they attempt to do so.

Trying to scalp the “Intention” set in particular actions could be complex but, using again our main referential model and variable (time), knowing that we can decompose it a in relation between velocity and space (time= velocity x space), we defined the decrease of velocity after losing the ball as the principal indicator to decide which option to choose in these situations.

In this way, we believe we have constructed a theoretically sound and coherent analysis matrix that allows, in a simplified but not reductive manner, the collection of data that, with proper treatment, can help define collective and individual behavioral trends that facilitate the formulation of conjectures to be tested and initiate a diagnosis that does not limit the search of causes to a single factor or a set of factors interpreted without an understanding of the dialectical relations established among them.

Based on the visible actions embodied in the game by the different players, with the necessary conceptual framework to understand in a contextualised way the meaning and significance of those same actions, the diagnosis can thus be guided by the inherent complexity of the phenomenon of sports practice based on the identified trends (hence the importance of a simple, coherent, and functional analysis tool) and in a logic of conjectures-refutations that does not exclude hypotheses from the outset and allows establishing causalities among the different performance factors and domains that could influence it (mastery of oneself, of the territory, and of social relationships).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

After all this journey that starts with coaches’ opinions and results on an exploration around the theoretical base that could allow us to interpret this phenomenon coherently aligned with its characteristics (and the builded analysis matrix in sequence), it seems to be possible to accept and confirm this work last two appointed hypotheses (D and E).

Many other questions arise when we attempt to anticipate the return that this challenge might bring. However, based on everything discussed so far, implementing a truly holistic logic (considering the various performance factors involved) of intervention, which places sports practice and its analysis at the center of action for the (trans)formation of individuals in this particular context, while constructing the necessary (material and conceptual) tools to ensure adaptability and effectiveness in the current conditions, seems to become an urgent challenge.

With this in mind, the broad and primary objective in the short term will necessarily involve testing and refuting the flexible diagnostic instrument presented here, which is in constant development (the dynamics and not finitude of the processes must always be kept in mind).

These tests should make it possible to assess its capacity to detect trends based on the categorization of actions in the game and, by relating these data with other informations from diverse sources, perceive its robustness in formulating deductive diagnoses concerning issues related to different performance factors (in this work, with a special focus on the psychological factor).

At this point, contextual non-replicability poses a challenge, making it highly inconsistent to generalise based on instruments specifically constructed to meet the particular necessities of a given reality (different sports, different sample characteristics, etc.). However, the challenge of managing the complexity of an interconnected network of components and structuring tools that effectively address the full range of needs felt in the field should not be ignored (Pereira et al., 2024).

If this proves to be consistent, many avenues for development may be pursued in the medium and long term, particularly through the experimentation of intervention protocols based on training tasks that could unveil their impact on the immediately above-mentioned factor, fulfilling the intention of strengthening a vision for sports training that can be identified as truly holistic.

This possibility, which departs from most compartmentalised approaches prevalent in this field (particularly concerning the psychological factor), while lacking the support of ongoing research protocols, nevertheless appears to offer a more efficient way of addressing the actual demands.

In sporting contexts, time is a finite capital, evaluating all the variables involved in the sports performance may lead us to a nowhere land but we also shouldn’t forget anything (a practical paradox), so it’s crucial to establish the bases to coherently integrate all the available data and define priorities. Sport ecologies have solicited the implementation of performance planning models based on principles of nonlinear dynamics (Pereira et al., 2024).

This first step may become, in a positive scenario, a fruitful avenue to aid in a better and greater understanding of the impact of this phenomenon on Man, positioning it at the forefront as one of the primary means available to Society to intervene in the educational/training sphere.

From this perspective, assuming that the training process is, by definition, unique and unrepeatable for each practitioner and occasion (establishing distinct boundaries for the intervention), experiencing the context in which it unfolds highlights the necessity for the coach to skilfully manage the tools that enable an individualised intervention (considering the characteristics, abilities, and potential of the practitioner) while ensuring it is sufficiently grounded (based on ongoing diagnoses/evaluations of the proposed intervention) and maintaining a constant awareness of the fallibility of their assumptions.

The analysis matrix presented here could represent a great help defining trends that guides the coach through plausible hypotheses to be tested, investigating the diverse causes that could be associated to the observed behaviors and, as a consequence, contributing to a better intervention and to know deeper the person who trains.

In future works, that requires transdisciplinary approaches and maybe new methodologies, it is necessary to understand how the observed behaviors and the detected trends through this matrix could have a correlation with the diverse psychological competencies/skills that probably influence the sporting performance. Therefore, there’s a huge research field to unfold.

CONCLUSIONS

If we consider this work initial aims and hypotheses, we can conclude that is possible to:

Confirm that this sample of top-level coaches seems to consider the psychological factor to be decisive in the practitioners’ performance;

Assume that these coaches affirm that it is possible to diagnose skills related to the psychological factor through the observation and analysis of practitioners’ behavior in training and competition;

Perceive a well-defined trend in this sample of coaches that points to the belief that the work of psychological skills can also be carried out through the design of training tasks;

Build, based in current authors and well-established references, a conceptual framework that embraces and allows to manage the holistic characteristics of the sports phenomenon, where complexity and non-linearity are constantly present;

Initiate a matrix structuration aligned with the principles above mentioned that allows to define trends in players’ behavior and test this new tool adaptability and validity.

This means that we achieved all the proposed aims and that we could accept the defined hypotheses, strengthen the conviction that the theoretical questions that emerge from our exploratory journey may have practical implications and make sense to the ones who deal with these issues on the field.

The obtained results could have an impact from amateur to professional football training (because it opens the door to new and more profitable visions of diagnosing competencies in all the performance factors), but also in the global sports area itself, help redefining concepts and strategies marked by a reductionism and positivism that mischaracterise Man.