INTRODUCTION

The rapid and global spread of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), along with its severity, led the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) to characterise the situation as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, causing a COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Immediate efforts were made by healthcare organisations and governmental authorities to contain the significant progression and spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome, resulting in improved pandemic control (Gomide, Abdalla et al., 2022).

In an effort to mitigate the effects of COVID-19, the American College of Sports Medicine suggests that moderate-intensity physical activity (PA) should be maintained during the quarantine period, emphasising the importance of staying physically active (Channappanavar & Perlman, 2017). Engaging in at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity or a minimum of 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week is advised to enhance immunity and improve overall health status (OHS) (Hamer & Chida, 2008; Lukács, 2021; Zheng et al., 2024). Despite the encouragement to maintain a physically active lifestyle during the period of combating the virus’s spread, the combination of isolation and social distancing measures resulted in a reduction in physical activity time and a consequent increase in sedentary behavior (SB) in the population (Ramos et al., 2022). This facilitated weight gains and the emergence of comorbidities associated with a higher cardiovascular risk, such as obesity, systemic arterial hypertension, and insulin resistance, which may represent a greater risk of negative outcomes in general health status (GHS). Furthermore, according to scientific literature, the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and mortality is reduced in individuals with physically active lifestyles (Barros et al., 2009).

Therefore, PA can help control several risk factors that increase the likelihood of negative health outcomes caused by COVID-19. For example, literature shows that COVID-19 diagnoses in overweight or obese individuals are associated with worse clinical outcomes (Ramos et al., 2022). Yet, the highest prevalence of COVID-19 diagnoses was observed among older people, likely attributed to risk factors that increase their susceptibility to adverse health outcomes. This is corroborated by data from a study conducted in Wuhan, China, the epicenter of the disease outbreak, where older individuals who succumbed to the virus had a high prevalence of systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus (Gomide, Mazzonetto et al., 2022). Although the influence of PA and SB in mitigating the effects of COVID-19 is widespread and recognised, there is a notable lack of information about the impact that COVID-19 has had on PA, SB, and the GHS.

Limited evidence in the literature has explored the impact of COVID-19 on PA, SB, and GHS. This study hypothesises that total PA, SB, and GHS worsened after recovery from COVID-19 due to symptoms and clinical outcomes. If confirmed, it would further highlight the importance of maintaining a physically active lifestyle, particularly during pandemics or periods of social isolation. Socioeconomic, geographic, and structural factors, along with personal characteristics such as age and sex, can contribute to reduced PA and a decline in GHS (Baqui et al., 2021). Given these considerations, the effects of COVID-19 on an active lifestyle and overall health vary based on a range of modifiable and non-modifiable variables. Therefore, this study aimed to compare total PA, SB, and GHS before diagnosis and after recovery among individuals diagnosed with COVID-19.

Additionally, we sought to assess the influence of COVID-19 symptoms, signals, and clinical outcomes on PA, SB, and GHS in both adults and older adults while considering potential confounding variables such as sex, nutritional status, and family income.

METHODS

Study design and ethical aspects

This is an observational study with a retrospective cross-sectional design. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Ribeirao Preto School of Nursing at the University of São Paulo (CAAE: 39645220.6.0000.5393) and met the guidelines governing research involving human beings, in accordance with the Resolution of the National Health Council (CNS) 510/16 (Lordello & Silva, 2017). Subsequently, an official request (462/2020) was submitted and approved by the Municipal Health Department of Ribeirao Preto to obtain information regarding participants’ names, telephone numbers, and email addresses. All purposes and methods employed in the study were explained to the participants, emphasising their right to withdraw from the research at any time. This manuscript followed the guidelines of The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) (Elm et al., 2007).

Data collection

The Municipal Health Department of Ribeirao Preto provided names, telephone numbers, and emails of 33,643 people diagnosed with COVID-19. This data collection, which took place through telephone calls, covered the period from March 2020 to January 2021. The sample size calculation considered a prevalence of hospitalisations due to SARS-CoV-2 of 10.0%, a precision of 1.5%, and a 95% confidence interval for a finite population of 34,742 infected individuals, resulting in a minimum sample size of 1,472 participants. Considering a sampling loss of 20%, the maximum number of interview attempts was 1,840.

Using Microsoft Excel®, seven trained evaluators supervised by the coordinator made 3,814 random telephone calls. Exclusion criteria were: presence of any conditions of immunological compromise, prolonged use including corticosteroids and/or chemotherapy, transplant patients, and presence of neurodegenerative diseases. Out of this total, 647 participants answered the calls after a maximum of three attempts. Data from 14 subjects were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria related to immunosuppressive conditions, and 124 people chose not to participate. Thus, 509 individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 were deemed eligible and interviewed, and their data were included in the present study. All participants in this study were asked about the pre-diagnosis period, referring to the week before testing positive for COVID-19, and the post-recovery period, during which they were asked about their current well-being. The data collection flowchart description has been previously published (Gomide, Mazzonetto et al., 2022).

The inclusion criteria adopted in the research were as follows: people aged ≥ 18 years, of both sexes, with a positive diagnosis for COVID-19, without immunosuppressive diseases (immunological compromise), and residing in the city of Ribeirao Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. Data from those who did not answer all the questions in the questionnaire were excluded. Participant recruitment and selection were conducted through telephone contact, with three attempts made. The researchers identified themselves and provided details about the research. Upon agreement to participate, the participant received the Informed Consent Form signed by the researcher and then commenced their participation. Google Forms® was used to create the forms and ensure all mandatory questions were answered. Thus, the data collection instrument was only considered complete if all the information was filled out at the end. To ensure the completeness of responses, the researcher read aloud what had been noted and asked the interviewee if it was correct.

Data collection – Questionnaires

Profile of people diagnosed with COVID-19

The “Profile of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19” instrument was developed by researchers based on their expertise in the subject and validated according to the guidelines described in the literature (Medeiros et al., 2015). The instrument consists of questions about personal characteristics, such as age, marital status, sex, education level, place of birth, skin color, family income, body weight, height, and the use of public or private healthcare systems. It also includes information about the participant’s health history, including the current pathology and past diseases such as systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune diseases. Body mass index (BMI) classification considered: BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), BMI > 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 (normal weight), BMI ≥ 25 to 29.9 kg /m2 (overweight) and BMI > 30.0 kg/m2 (obesity). Additionally, through this questionnaire, the GHS was assessed. The interviewee responded regarding the week before the COVID-19 diagnosis and the last seven days before the interview and was classified as excellent, very good, good, fair and poor. Each participant’s response was considered for analysis, and the median was considered.

Physical activity

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short version was used to assess SB (hours per day) and quantify the total time of PA (minutes per week) performed by the participants. This questionnaire has been validated in different countries, including Brazil (Matsudo et al., 2001). The total time of PA was assessed for the week before the COVID-19 diagnosis (pre-diagnosis) and in the seven days prior to the interview (post-recovery).

Statistical analysis

The results were double-checked to reduce coding errors and coded by two independent researchers. Non-parametric procedures were adopted because variables were non-normally distributed (after verification using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Results are presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies for categorical variables. Total PA (min), SB (hour), and GHS (score) are quantitative variables, and they were presented as median and percentiles 25th and 75th. For the quantitative variables, comparisons between pre-diagnosis and post-recovery were performed using the Wilcoxon test for paired samples. To verify the effect size of the impact of the COVID-19 infection on the participants’ total PA, SB, and GHS, we adopted the Cohen’s d (1988) reference values (d < .1 = negligible; d < .3 = small; d < .5 = medium; and d ≥ .5 = large). The Quade’s ANCOVA test verified the influence of COVID-19 signals, symptoms, and clinical outcomes on the total PA, SB, and GHS, controlled for confounding variables sex (male or female), BMI (≤ 24.9 kg/m2 or ≥ 25 kg/m2 and family income (≤ US$ 370 or ≥ US$ 371). The presentation of results and statistical analysis was prepared considering the group sample age (18 to 59 or ≥ 60 years old). All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 20.0 with a significance level of α = 5%.

RESULTS

Among the 509 participants, 78.0% were aged between 18 and 59 years and self-declared as White (59.1%), Brown (30.6%), and Black (10.3%). Regarding family income, 88.7% of adult participants reported an income greater than US$ 371; the percentage was 82.1% among the older adults. Regarding BMI, regardless of age group, the highest percentage was among those classified as normal weight.

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and BMI of participants diagnosed with COVID-19, referring to the post-recovery assessment.

Tabla 1 Study participants absolute and relative values of personal and sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variables | 18 a 59 years (n = 397) |

60 years (n = 112) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Male | 159 | 40.1 | 39 | 34.8 |

| Female | 238 | 59.9 | 73 | 65.2 | |

| Skin Color | White | 232 | 58.4 | 69 | 61.6 |

| Black | 36 | 9.1 | 12 | 10.7 | |

| Asian | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Brown | 126 | 31.7 | 30 | 26.8 | |

| Family Income | = $: 371 | 352 | 88.7 | 92 | 82.1 |

| < $: 370 | 45 | 11.3 | 20 | 17.9 | |

| Body Mass Index | < 24.9 kg/m2 | 273 | 68.8 | 92 | 82.1 |

| = 25.0 kg/m2 | 124 | 31.2 | 20 | 17.9 | |

Ribeirão Preto. Brazil. 2022.

Note: n: absolute frequency; %: relative frequency; =: greater than or equal to; <: less than; kg/m2: kilograms per square meter; BMI: body mass index; $: dollar.

In the pre-diagnosis period, adults had higher SB and worse GHS. Finally, in the post-recovery period of COVID-19, adults had more SB time, and older adults showed a greater deterioration in GHS (Table 2). Table 2 presents the comparative analysis of sociodemographic characteristics and BMI according to the age group of the participants in the pre- and post-recovery periods of COVID-19.

Tabla 2 Description of sociodemographic characteristics and body mass index according to the age group of participants in the pre- diagnosis and post-recovery periods of COVID-19.

| Variable | 18 to 59 years | = 60 years | U value | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Min-Max | p 25th-75th | Median | Min-Max | p 25th-75th | |||

| Height (cm) | 168.0 | 142–200 | 160.0–175.0 | 161.0 | 143–196 | 155.0–168.0 | 5.2 | < .001 |

| Body mass (kg) | 78.0 | 15.0–178.0 | 67.0–91.0 | 76.5 | 38.0–118.0 | 64.2–89.0 | 1.3 | .194 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 | 4.8-60.8 | 24.2-31.2 | 28.6 | 15.23–44.5 | 25.8–32.6 | –1.7 | .094 |

| Total time of PA – Pre- diagnosis (min/week) | 228.0 | 0.0–9629.0 | 52.5–521.5 | 187.5 | 0.0–4620.0 | 0.0–553.2 | .6 | .532 |

| Total time of PA – Post-recovery (min/week) | 149.0 | 0.0–9240.0 | 0.0–427.0 | 108.8 | 0.0–4620.0 | 0.0–502.8 | .8 | .409 |

| Sedentary behavior – Pre diagnosis (hour/day) | 3.5 | 0.37–11.0 | 1.50–5.5 | 3.5 | 0.51–11.0 | 1.5–4.7 | 3.0 | .003 |

| Sedentary behavior – Post-recovery (hour/day) | 3.5 | 0.37–11.0 | 2.07–6.35 | 3.5 | 0.11–11.0 | 1.5–5.5 | 2.2 | .028 |

| General health status – Pre diagnosis (score) | 4.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 3.0–5.0 | 3.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 3.0–4.0 | 5.0 | < .001 |

| General health status – Post-recovery (score) | 3.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 3.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 4.3 | < .001 |

Ribeirão Preto. Brazil. 2022.

Note: PA: physical activity; BMI: body mass index; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; P25: 25th percentile; P75: 75th percentile; U: U statistic value.

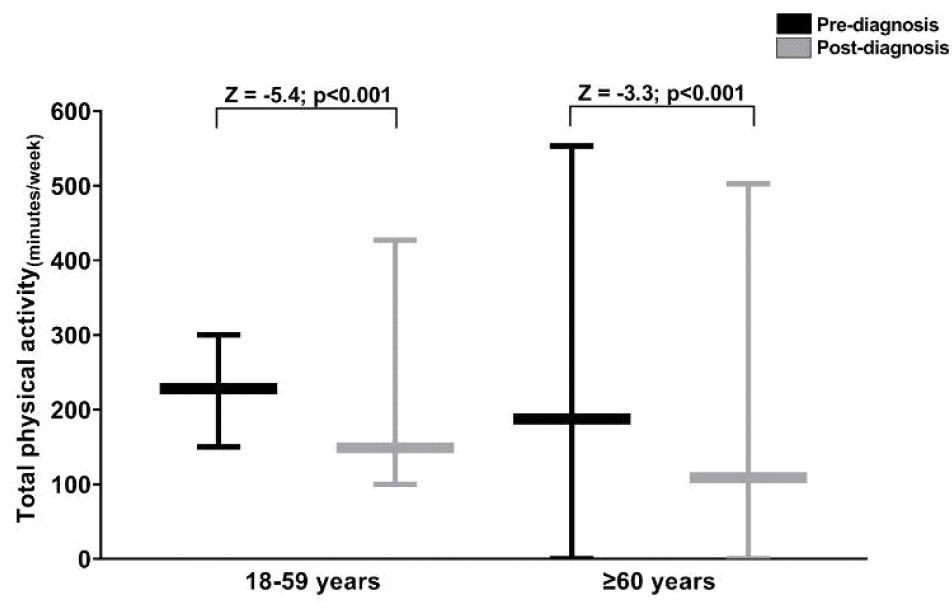

In Figure 1, a reduction on overall PA was observed between the pre-diagnosis and post-recovery periods for adults (Md-pre = 228 min/week; Md-post = 149 min/week; Z = –5.4; p < .001) and older adults (Md-pre = 187.5 min/week; Md-post = 108.7 min/week; Z = –5.4; p < 0.001).

Ribeirão Preto. Brazil. 2022.

Note: Z: z-statistic value.

Figure 1 Comparison of pre-diagnosis and post-recovery COVID-19 for total physical activity (18 to 59 years and ≥ 60 years).

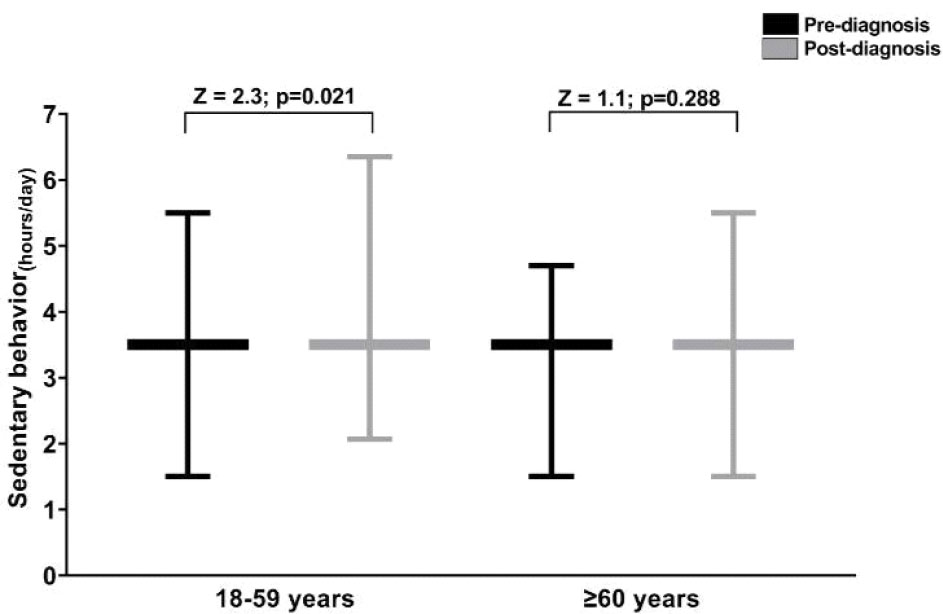

In Figure 2, an increase in SB was observed only in adults in the post-recovery period (Md-pre = 3.5 hours/day; Md-post = 3.5 hours/day; Z = –2.3; p = .021). The difference can be seen in the first and third quartile-percentile (pre: 25th = 1.50; 75th = 5.50; and post: 25th = 2.07; 75th = 6.35).

Ribeirão Preto. Brazil. 2022.

Note: Z: z-statistic value.

Figure 2 Comparison of pre-diagnosis and post-recovery for sedentary behavior (18 to 59 years and ≥ 60 years).

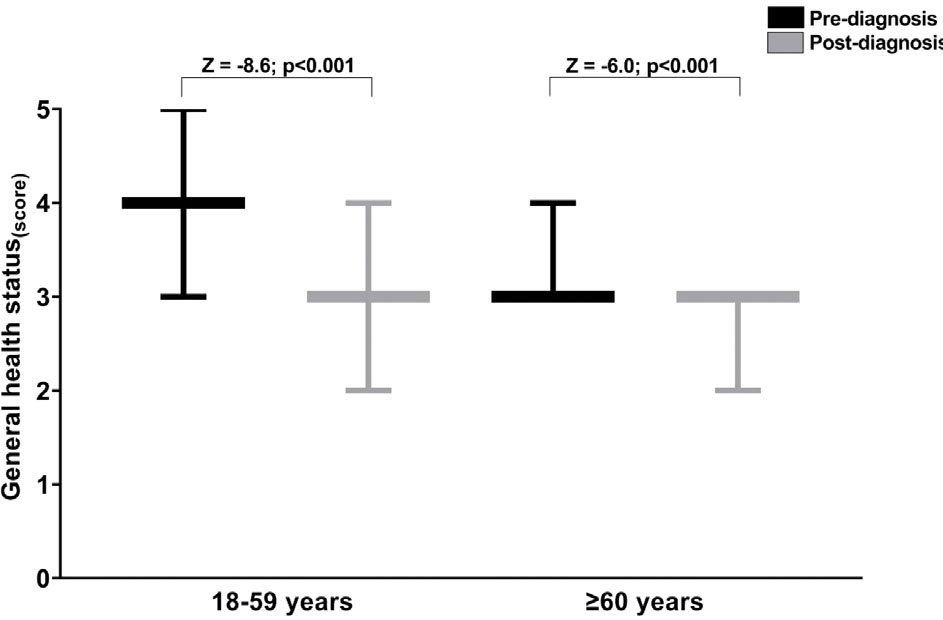

In Figure 3, a deterioration in GHS was observed for adults (Md-pre = 4.00; Md-post = 3.00; Z = –8.6; p < .001) and older adults (Md-pre = 3.00; Md-post = 3.00; Z = –6.0; p < .001). In older adults, the deterioration can be seen in the first and third quartile-percentile (pre: 25th = 3; 75th = 4; and post: 25th = 2; 75th = 3).

Ribeirão Preto. Brazil. 2022.

Note: Z: z-statistic value.

Figure 3 Comparison of pre-diagnosis and post-recovery COVID-19 for general health status (18 to 59 years and ≥ 60 years).

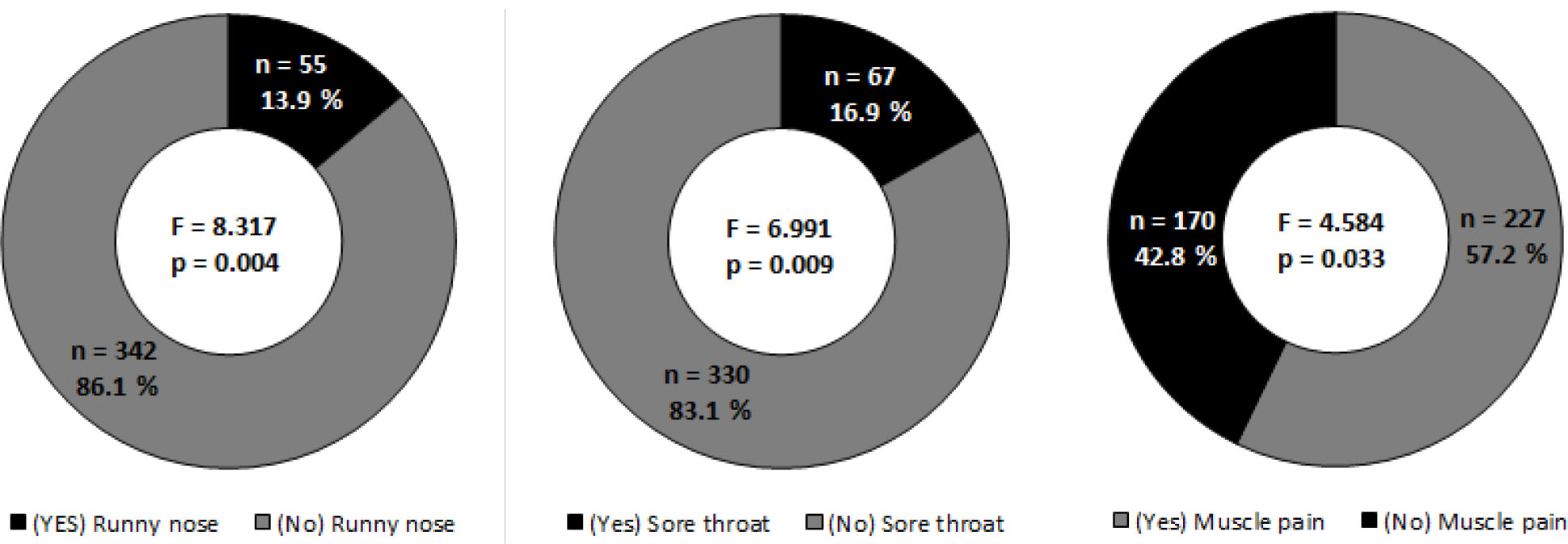

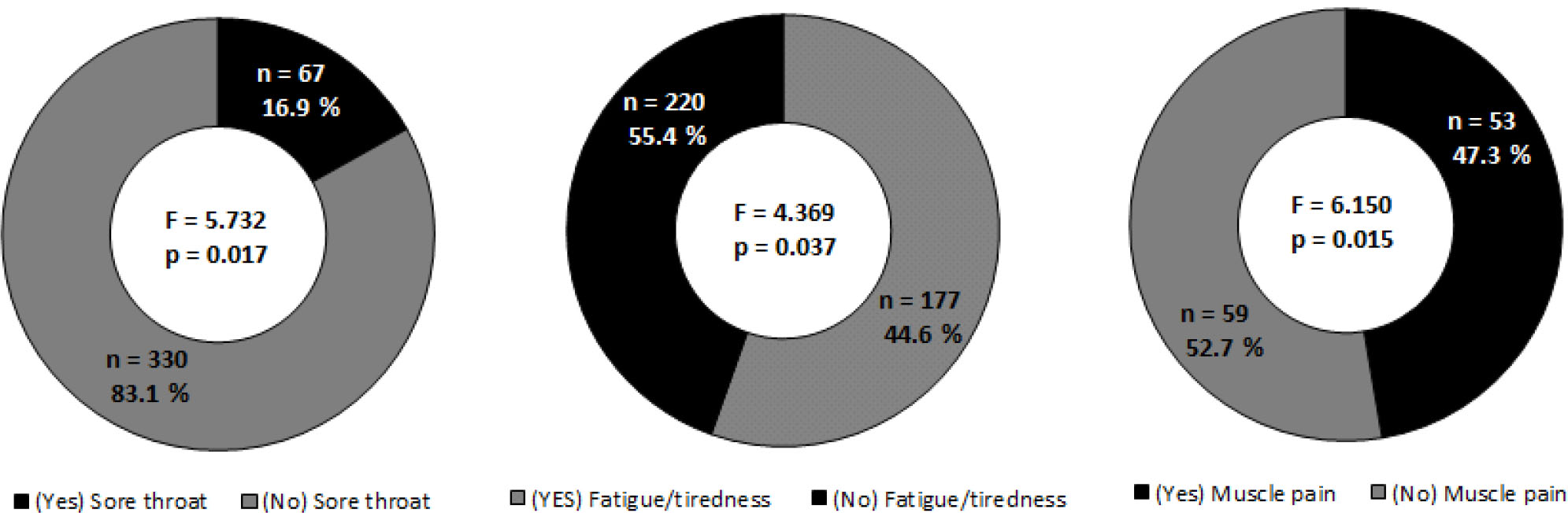

We presented only the signs, symptoms, and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 for which we verified statistical significance. After Quade’s ANCOVA test, Figure 4 shows the influence of COVID-19 signals, symptoms, and clinical outcomes on the total PA (Figuere 4A), SB (Figuere 4B), and GHS (Figure 4C) after controlling for sex, BMI, and family income for adults and older adults.

Figure 4 (C) Sore throat, fatigue/tiredness, and muscle pain influence on the general health status.

For adults, it was observed that runny nose (F = 8.317; p = .004), sore throat (F = 6.991; p = .009), and muscle pain (F = 4.584; p = .033) had a detrimental effect on overall PA. Additionally, the effect size of the impact of COVID-19 on overall PA was classified as small (d = .27) and medium (d = .31) for adults and older adults, respectively.

Dyspnea (F = 4.134; p = .043) and the requirement for oxygen support (F = 4.258; p = .040) were observed to affect SB adversely among adults. Similarly, the findings for older adults mirrored these results, indicating that dyspnea (F = 4.258; p = .040) and the need for oxygen support (F = 4.134; p = .043) had a negative impact on SB. Furthermore, the effect size of the influence of COVID-19 on SB was considered small (d = .11).

Finally, sore throat (F = 5.732; p = .017), fatigue/tiredness (F = 4.369; p = .037), and muscle pain influence (F = 6.150; p = .015) negatively influenced GHS in both group range. Additionally, the effect size of the influence of COVID-19 on GHS was considered medium (d = .43) for adults and large (d = .57) for older adults, respectively. Moreover, sore throat (F = 5.732; p = .017) and fatigue/tiredness (F = 4.369; p = .037) were found to adversely affect the General Health Status in adults. For older adults, muscle pain (F = 6.150; p = .015) had a negative impact on GHS.

DISCUSSION

The study aimed to verify the impact of PA, SB, and GHS on pre-diagnosis and post-recovery of people diagnosed with COVID-19. There was a noticeable decrease in both overall PA and the perception of GHS among both adults and older adults when comparing pre-recovery to post-recovery stages. After recovering from COVID-19, SB notably increased in adults. Furthermore, runny nose, sore throat, and muscle pain had adverse effects on overall PA in both adults and older adults. Among older adults, dyspnea and the need for oxygen support negatively impacted SB. In both adult groups, sore throat, fatigue/tiredness, and muscle pain were found to negatively affect GHS, even after accounting for variables such as sex, BMI, and family income. The confirmation of our study hypothesis underscores the necessity for synchronous or asynchronous interventions within society to maintain and promote an active lifestyle, particularly during times of pandemic or specific social isolation requirements.

The reduction in overall PA between the pre-diagnosis and post-recovery periods for adults and older adults was also observed in other studies. Studies conducted in Sweden (Lindberg et al., 2023) and Brazil (Caputo & Reichert, 2020) among adults and older adults yielded results similar to those of the current research, where PA levels decreased in the early stages of the pandemic (Lindberg et al., 2023), and the most significant decline occurred due to social distancing measures adopted during the pandemic period (Caputo & Reichert, 2020). The prolonged duration of the pandemic in these two countries and the population’s prolonged indoor confinement can account for the decline from the pandemic’s onset to its later stages. A systematic review and meta-analysis detected changes in PA patterns due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 14 countries worldwide. The results of most studies also revealed a significant decline in PA, and PA decreased across all age groups (Wunsch et al., 2022). In the present research, a significant reduction in total PA time was observed in adults and older adults when comparing the pre-diagnosis and post-recovery periods of COVID-19. This finding aligns with a study conducted by Lindberg et al. (2023), which investigated the Swedish population across different age groups. The results of this study showed a similar trend, with a progressive decrease in PA, which is more pronounced among older adults. This decrease in PA during the pandemic was also highlighted in a scoping review addressing the impact of COVID-19 on PA (Lindberg et al., 2023; Stockwell et al., 2021). The systematic review and meta-analysis encompassing data from 14 countries corroborated our findings, demonstrating changes in PA patterns due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Wunsch et al., 2022). These findings indicate that the pandemic had a significantly detrimental impact on population health (Folk et al., 2021), resulting in a sharp decline in PA in the post-pandemic period. Therefore, the findings of these studies underscore the need for targeted interventions to promote PA and mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic on population health.

The symptoms of runny nose, sore throat, and muscle pain negatively impacted total PA time in adults and older adults. These symptoms could negatively affect their perception of quality of life, leading to a decrease in PA and, consequently, a deterioration of the immune system. In Filgueira’s study (2021), it was observed that maintaining PA influences the immune system. Increasing PA could be a promising strategy to enhance defenses against severe forms of COVID-19 (Filgueira et al., 2021). In El-Anwar’s study (2020) with 1,773 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, the occurrence of sore throat (11.3%) and runny nose (2.1%) was similar to our findings (El-Anwar et al., 2020). In Czubak’s systematic review (2021), muscle pain (29%) was indicated as one of the main symptoms of COVID-19 (Czubak et al., 2021), a result consistent with our findings.

We observed an increase in SB only in adults in the post-recovery period of COVID-19. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in the Swedish population, which showed a notable increase in SB in the adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lindberg et al., 2023). As observed in international studies, the increase in SB can be partly attributed to the more severe symptoms caused by COVID-19 (El-Anwar et al., 2020). Notably, the persistent increase in SB even after recovering from COVID-19 may be linked to the condition known as “Long COVID”. This condition affects a portion of the population with a mild form of the disease but experiences more severe and prolonged symptoms (Srikanth et al., 2023). Therefore, these findings highlight the importance of monitoring and addressing SB in adults, especially those who have experienced COVID-19, considering the possible influence of symptom severity and disease duration (Huang et al., 2023). Dyspnea and the need for oxygen support negatively impacted adults. In a cross-sectional study with Brazilians, it was observed that patients with a better level of PA had a lower number of hospitalisations and, consequently, a lower need for oxygen support (Gomide, Abdalla et al., 2022). During the pandemic, one of the main challenges faced by patients was dyspnea due to a lack of oxygen support, making it one of the major contributors to the increased mortality rate (Purnomo et al., 2021). We observed a decline in GHS for adults and older adults. A national study with the adult population indicated that GHS worsened to the extent that it interfered with daily tasks (Carvalho et al., 2021; Moraes et al., 2011). This deterioration during the COVID-19 pandemic was possibly caused by isolation and social distancing in addition to the presence of persistent symptoms of the disease.

Our study had some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, there was a disparity in the sample size, with 112 older adults compared to 397 adults aged 18 to 59. Although we controlled age in our analyses, this discrepancy may have influenced our findings. Additionally, one limitation was that we did not define a specific post-COVID-19 recovery period for analysis, which could have provided more consistency in the data. Furthermore, it is essential to note that our study is purely observational, and therefore, we cannot establish causal links between COVID-19 and the impairments in PA, SB, and GHS. The retrospective nature of this study brings together potential sources of bias, including issues related to memory, mental status, and health conditions among participants. To mitigate these biases, all evaluators underwent training. Ultimately, recognising that our sample is limited to residents of Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, is crucial. This constraint restricts the generalizability of our findings to other contexts.

On a positive note, the study has some strengths. Notably, our sample was collected prior to the administration of COVID-19 vaccines (before January 17, 2021), eliminating potential vaccination-related biases. The interviews were conducted by the study’s researchers, ensuring control and localisation of the sample within Ribeirao Preto. Additionally, we employed two questionnaires validated in Brazil, enhancing the reliability of our measurements.

Our findings hold significant implications for science, society, and public policy. The study highlights the significant impact of COVID-19 on PA, SB, and GHS in both adult and older adult populations. The noticeable decrease in PA and GHS, coupled with the rise in SB among adults post-recovery from COVID-19, emphasises the enduring effects of the virus on individuals’ overall well-being. Furthermore, our identification of specific symptoms, such as runny nose, sore throat, and muscle pain, as negative influences of PA, and symptoms like dyspnea and the need for oxygen support as factors affecting SB among older adults, highlights the multifaceted challenges posed by COVID-19. This understanding has the potential to influence public health strategies, direct rehabilitation initiatives, and enhance our comprehension of the pandemic’s lasting effects on the health and lifestyles of affected individuals. This knowledge can assist policymakers in developing precise interventions and support mechanisms. Building upon our study’s findings, several avenues for future research emerge. Firstly, further investigations can delve into the underlying mechanisms that link COVID-19 symptoms, such as sore throat, fatigue, and muscle pain, to reduced PA and GHS. Understanding the physiological and psychological factors at play could lead to more tailored interventions. Additionally, longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the long-term effects of COVID-19 on PA, SB, and GHS, as our research primarily captures post-recovery outcomes. Moreover, exploring the impact of vaccination on these parameters and comparing the experiences of COVID-19 survivors and vaccinated individuals could offer insights into the role of vaccination in post-pandemic recovery. Furthermore, investigations into strategies for mitigating the negative effects of COVID-19 on PA, such as home-based exercise programs or telemedicine interventions, could prove beneficial for affected populations. Lastly, expanding the research to encompass a wider geographical and cultural diversity would enhance the generalizability of the findings and facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the global implications of COVID-19 on physical health and well-being.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the enduring impact of COVID-19 on PA, SB, and GHS among adults and older adults. We observed reduced PA and GHS, alongside elevated SB in adults after recovery, signaling considerable effects on overall health. Additionally, the acknowledgment of distinct COVID-19 symptoms as enduring adverse factors, even after accounting for essential variables, highlights the intricate difficulties presented by the illness. Our findings endorse the necessity of specific interventions and support for individuals, particularly those who have had COVID-19, aiming to enhance their PA and overall health. In the broader realm of public health, our results underscore the requirement for a comprehensive and ongoing response to the pandemic that addresses not only immediate healthcare but also persistent health challenges. While navigating the continually changing landscape of COVID-19, our study illustrates the resilience of scientific investigation and its capacity to guide evidence-based strategies for safeguarding and improving community well-being.