INTRODUCTION

The credibility of sport as a social phenomenon is currently the subject of unprecedented debate (Harvey, 2015; Scambler, 2005). Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to maintain integrity to ensure that sport remains a safe, equitable, and inclusive activity for the countless individuals worldwide who actively participate in and follow sport (Scambler, 2005). At the same time, there are several implicit challenges (such as management inaction) and explicit threats (such as match-fixing, vote-rigging, and doping) that pose risks to the integrity of sport (Harvey, 2015). In terms of how the game is played and managed, the concept of integrity in sports is becoming an increasingly critical issue in global sports and their governance. A growing body of academic research has identified several areas of concern that policymakers and administrators of sports organisations need to address to safeguard the integrity of sport (Bayle, 2020; Boudreaux et al., 2016), such as manipulation of sports and sports betting (Hartill, 2013; Hill, 2013), doping (Bloodworth & McNamee, 2017; Heinrich & Brown, 2017; Hu et al., 2020), and human rights concerns (Adams & Piekarz, 2015; Giulianotti & McArdle, 2014).

Historically, sports-related social sciences and investigative sports journalism have played a crucial role in exposing financial corruption in sports. Scientific evidence over recent years highlights that corruption has been a persistent issue, with its prominence in sports such as boxing and baseball since the early 20th century since the early 20th century (Dixon, 2016). In the contemporary context, corruption is often linked with other irregularities such as electoral fraud, nepotism, and misappropriation of funds (Albergotti & O’Connell, 2013; Blake & Calvert, 2015; Ferguson, 2016; Woolf, 2012). One issue that has recently gained considerable attention is match-fixing, particularly due to its association with unregulated gambling, referred to as “narrow sport integrity,” which distinguishes itself from broader ethical concerns in sports (Hamil et al., 2004). In May 2013, global sports ministers convened in Berlin to address these critical challenges, including match-fixing, illegal betting, doping, and corruption, aiming to bolster the capacities of national and international sports federations to manage such issues. The effort to combat unregulated gambling and its links to match-fixing underscores the necessity for cross-border cooperation involving law enforcement and international organisations such as Transparency International, Europol, and Interpol. Establishing robust governance structures is essential, especially considering the regional disparities in tolerance for unregulated gambling, which complicates the creation of consistent global quality assurance policies (Dowling et al., 2018).

In this context, transparency has garnered increasing interest among researchers, both as a broad conceptual framework and specifically within the context of nonprofit organisations (Auger, 2014; Birchall, 2011). Within sports organisations, transparency is often defined as “clarity in processes and decision-making, especially when it comes to resource allocation” (Henne & Pape, 2018). This definition expands to include the accessibility of information to those impacted by organisational decisions, emphasising the importance of presenting information in a clear and understandable manner (Gardiner et al., 2017). Consequently, transparency and integrity in sports have been reconceptualised to cover various essential aspects, including ethical conduct and the responsibility of stakeholders to uphold fundamental values such as fairness, respect, and excellence (Gardiner et al., 2017; Scambler, 2005). These concepts require continuous dialogue among stakeholders about aligning values and practices with ethical standards.

Interest in sports governance, particularly concerning transparency and integrity, has seen significant growth both in academic circles (Dowling et al., 2018; Ferkins et al., 2005; Henne & Pape, 2018) and among policymakers at various levels. The emergence of trends such as increased commercialisation, greater professionalism, and expanded governmental involvement in sports management calls for more structured systems and governance principles (Henne & Pape, 2018). The recent scrutiny of governance structures and decision-making processes within sports organisations reflects broader concerns about ethical conduct and accountability. The substantial autonomy sports organisations enjoy, combined with their increasingly commercialised environments (Henry & Lee, 2004; Lam, 2014), has raised critical questions about their legitimacy. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop criteria and indicators that define optimal governance practices and ethical standards within sports organisations (Dowling et al., 2018).

Recently, the governance structures and decision-making processes of sports governing bodies have come under intense scrutiny. This challenge is not unique to national or international sports organisations; they all face various risks related to ethically sensitive issues (Bloodworth & McNamee, 2017; Henry & Lee, 2004). Several of these organisations have been criticised in the past for the way they have handled various issues (Henry & Lee, 2004). The considerable autonomy that sports organisations enjoy, the highly regulated environment in which they operate, and the increasing commercialisation of sports have raised questions about the legitimacy of these organisations (Henry & Lee, 2004; Lam, 2014). This should result in developing criteria and indicators that define optimal governance practices and ethical conduct within the context of sports organisations.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of transparency and integrity in sports organisations, there is still a clear lack of standardised instruments to effectively measure these concepts. Most existing approaches rely on qualitative evaluations or subjective reviews, leading to methodological inconsistencies across studies. While some indices have been developed for specific contexts, there remains a notable gap in validated questionnaires that can accurately and uniformly assess integrity and transparency across various sports organisations. This lack of robust tools hinders inter-institutional comparisons and the implementation of improvements based on reliable data. Therefore, the development of a validated instrument to measure these indicators is crucial for continuous progress in the ethical management of sports. Given the growing concerns about ethical misconduct and integrity issues in sports, this study aims to develop and validate a Transparency Index. This tool is designed to systematically measure and assess integrity and transparency within sports organisations.

METHODOLOGY

Development of the instrument

The first set of items of the Transparency Index consisted of 15 items and was developed based on the three domains of interest identified for this scale in the literature review: Organisational/ governance, operational and financial. The selection and formulation of these items were grounded in a detailed analysis of transparency practices and principles discussed in academic literature. Previous studies highlight the importance of transparency across various aspects of organisations, emphasising that effective governance requires clarity in decision-making processes and organisational management (Auger, 2014; Birchall, 2011). Literature also underscores the need for transparent operational practices to ensure that daily activities are conducted responsibly and aligned with organisational goals. Additionally, financial transparency is often associated with integrity and trust in organisations, with a focus on clear and accessible disclosure of financial information (Henne & Pape, 2018). These principles informed the choice of items for the index, ensuring that they comprehensively address critical areas for evaluating transparency in organisations.

This draft was sent to nine experts in sports, including university professors and researchers, to evaluate the “degree of adequacy of the item to the assessment of transparency” on a scale that varied from 0- Not appropriate to 5- Very appropriate, aiming to test content validity. The quantitative results showed that items showing the lowest level of adequacy: a) items with the lowest minimum adequacy values are 11, 15, and 10; b) items with the lower average adequacy obtained by all responses are items 11, 14, and 15, and c) items with the greatest variability in adequacy was items 15, 10, and 11 showed significant variability in adequacy ratings, with high standard deviations. Despite these results, the experts chose to keep both items to see how they would behave in the next phase of the study. The final questionnaire was thus identical to the draft and had a total of 15 items: 1) Governance / Organisational Structure, 2) Code of Conduct, 3) Board Membership, 4) Membership (in organisations), 5) List of Sponsors / Partners, 6) General Assembly, 7) Equal Opportunities and Diversity Policy, 8) Data Privacy and Security Policy, 9) Whistle-blower Policy, 10) Consultation / Stakeholder Engagement Policy, 11) Sports Betting Policy and Policies, 12) Accounting Standards, 13) Financial Disclosure and Reporting, 14) Procurement Policy, 15) Anti-Corruption Policy.

Data collection

For validation of the Transparency Index, the questionnaire was sent to 11 sports experts to evaluate the websites of 196 sports institutions via e-mail. Sports institutions were distributed by 7 levels of sports organisations, namely: 1) Umbrella World Organisation (UWO); 2) World Federations (WF); 3) European Federations (EF); 4) Umbrella National organisation (UNO); 5) National Federations (NF); 6) Regional Associations (RA); 7) Clubs (CL). The experts received detailed information about the study and the questionnaire during a session that occurred on 8th April 2024. The return of the questionnaires was considered consent for participation. The selection criteria used considered them to have previous training, knowledge, and aptitude for the purpose. Furthermore, participation in a training session for the response to the instrument was mandatory.

Statistical methods

The present study is exploratory and employs a cross-sectional design. Descriptive statistics (percentages, mean scores, and standard deviations) were calculated for data obtained with the Transparency Index. Reliability was measured through internal consistency using the following techniques and cut-offs: mean of the inter-item correlation (adequate if > 0.30), corrected item-total correlation (adequate if > 0.50) (Hu et al., 2020) and Cronbach’s alpha (sufficient if > 0.50 for early stages of research) (Auger, 2014).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) were performed to test sample adequacy (Cicatiello et al., 2017). A KMO criterion of 0.50 is barely acceptable. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the method of analysing main components and varimax rotation was used to test preliminarily the model fit of the Transparency Index. To assess between-institutions differences, the Kruskal-Wallis test (H) was used, as well as to assess differences between the 3 evaluators. Statistical analyses were considered at a 0.05 significance level. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Statistics version 21).

RESULTS

Score scale items

The descriptive analysis of the Transparency Index items presents means from .02 (Item 11) to .88 (Items 1 and 3) and statistical deviations from .14 (Item 11) to .5 (Item 2). Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for each item, as well as the total number of answers obtained for each item (missing values are not a problem at all in the data obtained). Descriptive statistics of the overall result vary from 0 (Min.) to 13 (Maximum), with a Mean of 6.54 (Standard deviation = 2.88).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of isolated items.

| Items | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Item1 | .88 | .33 |

| Item2 | .50 | .50 |

| Item3 | .88 | .33 |

| Item4 | .61 | .49 |

| Item5 | .78 | .41 |

| Item6 | .45 | .50 |

| Item7 | .24 | .43 |

| Item8 | .56 | .50 |

| Item9 | .19 | .39 |

| Item10 | .13 | .33 |

| Item11 | .02 | .14 |

| Item12 | .36 | .48 |

| Item13 | .61 | .49 |

| Item14 | .22 | .41 |

| Item15 | .18 | .39 |

Note: 256 cases were registered for each item.

Reliability statistics

The Transparency Index with 15 items had sufficient reliability, with Cronbach’s α = .72. However, items 9 and 10 present a correlation less than 0.1 and present greater values of Cronbach’s alpha if they are deleted, .73. Therefore, we studied a solution without these two items. The Transparency Index with 13 items presents a Cronbach’s α = .74.

Test dimensionality

A principal axis factor analysis was conducted on 13 items with varimax rotation.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis, KMO = .69 (which is above the acceptable limit of .5). An initial analysis was run to obtain eigenvalues for each factor in the data. Four factors had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and, in combination, explained 56.53% of the variance. The scree plot was ambiguous and showed inflexions that would justify retaining either 2 or 4 factors. We retained 4 factors because of the large sample size, the convergence of the scree plot and Kaiser’s criterion on this value and the accordance with based theory. The items that cluster on the same factor suggest that factor 1 represents organisational/governance (composed by items 1,2,3,4,6 and 12), factor 2 represents financial (composed by items 13, 14 and 15), 3 represents operational diversity inclusion policy (consisting of single item 7) and 4 represents partner and sponsor collaboration (consisting on single item 5).

Construct validity

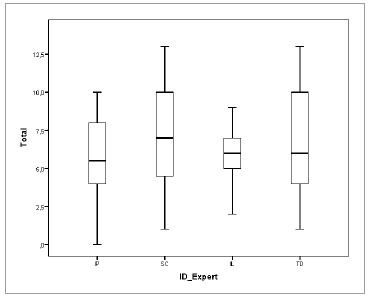

Results by evaluator

A Kruskal-Wallis test showed that there are no significant differences between evaluators, H (3) = 1.85, p = .6, with total means ranging from 5.65 to 7 and medians from 5.5 to 7, as can be observed in Figure 1. Detailed, evaluator IP presented a mean of 5.65 (SD = .65) and a median of 5.5; evaluator SC a mean and median of 7 (SD = .83); evaluator IL a mean of 6.15 (SD = .43) and a median of 6; and the last evaluator a mean of 6.76 (SD = .85) and a median of 6.

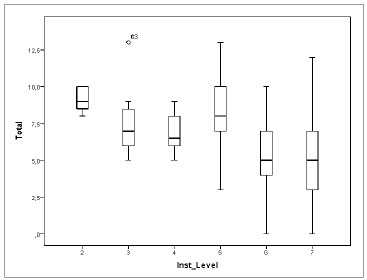

Results by institution level

Total of Transparency Index was significantly affected by Institution level, as evaluated by Kruskal Wallis, H (5) = 63.29, p < .01, with Levels 2 - World Federations (WF) (Mdn = 9.14), 5 - National Federations (NF) (Mdn = 8.11) and 3 - European Federations (EF) (Mdn = 7.71) with higher total results, and Level 6 - Regional Associations (RA) (Mdn = 5.29) with the lowest (Table 2).

Table 2. Transparency Index total evaluates institutions by organizational level.

| Level | Mean | N | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 9.14 | 7 | 0.90 |

| 3 | 7.71 | 7 | 2.69 |

| 4 | 6.83 | 6 | 1.47 |

| 5 | 8.11 | 94 | 2.34 |

| 6 | 5.29 | 42 | 2.62 |

| 7 | 5.31 | 100 | 2.86 |

| Total | 6.54 | 256 | 2.88 |

It is also possible to observe in Figure 2 a higher heterogeneity of the Transparency Index total of the institutions of levels 5 - National Federations (NF), 6 - Regional Associations (RA) and 7 - Clubs (CL).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to develop and validate the Transparency Index to assess transparency in sports organisations. By identifying fundamental indicators of these characteristics, the Transparency Index will provide a mechanism for evaluating and enhancing the integrity and transparency of sports institutions. The results indicate that the Transparency Index exhibits psychometric properties within an acceptable range.

Adequate overall reliability of Cronbach’s α = .72 (Auger, 2014) for the initial 15 items presents an equivalent internal consistency, increasing to 0.74 when items 9 and 10, which showed low correlations, were removed. Factor analysis identified a four-factor solution, representing organisational governance, financial transparency, diversity and inclusion policies, and collaboration with partners, explaining 56.53% of the total variance. There were no significant differences between evaluators, indicating consistency in the application of the index across different evaluators. However, significant differences were observed between institutional levels, with World and National Federations showing higher transparency scores compared to Regional Associations (Charron et al., 2014; Pina et al., 2007; Relly & Sabharwal, 2009), which had the lowest scores. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring and reinforcing transparency policies at different levels of sports governance to ensure consistent and fair practices (Adams & Piekarz, 2015; Albergotti & O’Connell, 2013).

This exploratory analysis suggests the possibility of a solution with four factors: organisational/governance (comprising items 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6), financial (comprising items 12, 13, 14, and 15), operational diversity inclusion policy (consisting of single item 7), and partner and sponsor collaboration (consisting of single item 5). These factors highlight critical areas for robust governance that are aligned with general principles of transparency and ethics. Moreover, the results reveal no significant differences between evaluators, validating the construct consistency of the Transparency Index. However, significant differences were observed between different institutional levels, with world, national, and European federations showing the highest transparency levels, while regional associations displayed the lowest indices.

The sport governance model is one of the primary indicators of integrity and transparency in sport and has become a significant concern for sports organisations (Chappelet, 2008; Dowling et al., 2018; Ferkins et al., 2005; Girginov, 2023; Hughes, 2017). A robust governance model implies that an organisation publicly discloses a well-defined organisational structure, an official constitution, and a governance model (Hughes, 2017). This includes accessibility to the organisation’s bylaws and the dates and minutes of board and committee meetings to all members (Aucoin & Heintzman, 2000; Bovens, 2007).

Accountability is also a critical indicator of transparency. In the context of sports organisations, accountability involves a clear link between individuals or entities and the organisation, ensuring that actions are clarified, validated, and subject to scrutiny. This mechanism helps prevent issues such as corruption and concentration of power, promoting effective governance and democracy (Aucoin & Heintzman, 2000; Bovens, 2007). A systemic approach to integrity and integrated accountability mechanisms is essential for overseeing power and preventing corruption, ensuring that transparency in accountability is maintained. Furthermore, research supports that fiscal transparency and the interaction between transparency and taxation are vital for good governance (Cicatiello et al., 2017).

Another crucial aspect of organisational transparency is the organisational structure, which defines the roles and functions of various components within a sports organisation. This information, typically available on the organisation’s website, helps stakeholders understand internal dynamics and the responsibilities of key individuals. Similarly, maintaining a publicly accessible membership listing and a clearly documented organisational hierarchy enhances trust and accountability (Chappelet, 2008; Cicatiello et al., 2017).

An ethics and compliance office or committee is another vital indicator of a sports organisation’s commitment to ethical conduct and regulatory compliance. This office should have its contact details and activities clearly displayed on the organisation’s website. While anti-corruption conventions address various types of corruption, including financial incentives to manipulate sporting events, a dedicated ethics office helps uphold integrity and prevent misconduct (Chappelet, 2018).

Effective leadership is fundamental to promoting transparency and integrity. Leaders, whether a board of directors, a CEO, or a combination of both, are crucial in setting ethical standards and fostering a culture of transparency within the organisation (Bradford, 1998). Leaders must establish clear guidelines, communicate expectations, and model ethical conduct, thereby facilitating trust among stakeholders and demonstrating a commitment to transparency. A democratic process, including free and fair elections for leaders and council members, is essential for good governance in sports organisations. Key principles such as the separation of powers and decentralisation also contribute to effective governance (Demise, 2006; Enjolras & Waldahl, 2010; Getz et al., 2015). Budget transparency plays a significant role in promoting accountability and public trust, while general assembly records, annual reports, and a well-defined constitution are integral to ensuring transparency, accountability, and ethical conduct (King, 2016).

In terms of practical application, the Transparency Index can serve as a valuable tool for monitoring and improving governance practices in sports organisations (Chappelet, 2018; Girginov, 2023; Howe & Haigh, 2016; Hughes, 2017). The identification of specific indicators, such as financial reporting, organisational structure, and the existence of an ethics office, is crucial for strengthening integrity and ethics within organisations. Utilising these indicators can foster greater trust among stakeholders, including athletes, fans, and sponsors, and help in preventing corruption and misconduct. Ultimately, it supports the development of governance structures that promote ethical behaviour and responsible management (Bloodworth & McNamee, 2017; Scambler, 2005).

Limitations of this study include the need to apply the Transparency Index to a broader sample of sports organisations to validate its applicability across different contexts. Future studies should consider expanding the index to include other potential dimensions of transparency and test its effectiveness in various settings to enhance understanding of governance practices in sports. The capacity to measure and assess these indicators is of paramount importance for the integrity and transparency of the field of sport, providing a foundation for ethical practices and fair play.

Current research underscores the importance of incorporating solid governance principles, such as financial transparency and accountability, while emphasising the need for clear organisational structures, including the definition of missions, codes of conduct, and democratic leadership procedures. Implementing these indicators, covering organisational structure, operational processes, and financial policies, not only provides a robust framework for analysing the performance of organisations but also serves as a reliable barometer for measuring their commitment to ethical conduct. These insights highlight the complexity of governance in sports organisations and the importance of balancing financial success with sporting integrity. Promoting effective governance mechanisms, building reliable leadership teams, and ensuring ethical and compliance policies are fundamental to maintaining the integrity, transparency, and trust of stakeholders in sports organisations.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of transparency and effective governance in sports organisations is undeniable. This study highlights the satisfactory internal consistency of the Transparency Index, suggesting that a version with 13 items, excluding items 9 and 10, presents slightly higher reliability compared to the original 15-item scale. Nonetheless, both versions demonstrate adequate internal consistency for assessing transparency in sports organisations. This exploratory analysis suggests the possibility of a four-factor solution: organisational/governance (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12), financial (items 13, 14, 15), operational diversity inclusion policy (item 7), and partner/sponsor collaboration (item 5). These factors emphasise key areas for strong governance that are aligned with principles of transparency and ethics.