Introduction

Human tooth loss results from multiple factors, including poor oral hygiene, limited access to dental services, poor systemic health, trauma, low socioeconomic status, among others.

Older adults are particularly affected by this condition, and edentulism is associated with a progressive deterioration in their quality of life. Despite the numerous advantages of fixed oral rehabilitation, it is still underutilized in older patients due to both economic and clinical constraints. Accordingly, conventional removable dentures still play a pivotal role in restoring oral function.1

Complete edentulism is of particular concern, namely in the mandibular arch. In fact, tooth loss induces morphological changes of the mandible that ultimately lead to residual ridge resorption. Under these conditions, conventional mandibular complete dentures have low retention and stability, generally resulting in discomfort, impaired function, and psychological problems for the patient.2 In the presence of few remaining natural teeth, however, these can be used as abutments for complete removable dentures. This strategy, known as tooth‑supported overdenture, relies on attachment systems that enhance retention, support, and stability of the denture, while also reducing alveolar bone resorption and maintaining proprioception, which, collectively, improve patient comfort and satisfaction.1 In addition, tooth‑supported attachments allow better occlusal distribution and absorption of masticatory forces.3

A variety of overdenture attachments are available. Based on resiliency, they can be divided into resilient or rigid, with the former being more efficient in protecting abutment teeth from occlusal forces. In terms of design, overdenture attachments can be classified as studs or bars, depending on whether the denture base is connected to each tooth individually or to splinted abutment teeth, respectively.3 Bal ‑ type attachments constitute a valuable option to improve the retention and support of overdentures. Some studies document their efficiency, suggesting that this type of attachment is the most appropriate due to the minimal transference of forces to the abutment teeth.4,5,6

Although tooth‑supported overdentures have numerous advantages and benefits, potential problems associated with the denture manufacturing and maintenance may arise. Besides denture fracture, loss of occlusal vertical dimension and the need of relining upon residual ridge resorption of distal edentulous areas, the most commonly reported failures are related to the loss (due to secondary caries or periodontal problems) or fracture of abutment teeth and/or the loss of retention of the attachment system.7,8 When the retention loss in overdenture attachments involves the female part of the system, replacement of the Teflon caps embedded in the denture easily solves the problem. On the other hand, when it arises from deterioration or wear of the metal in the male component, more complex medical procedures may be needed.

The present clinical report aims to describe a conservative and non‑nvasive procedure to overcome the loss of retention in a tooth‑supported overdenture caused by worn ball attachments.

Case report

An 80‑year‑old female patient, dissatisfied with the lack of retention of her mandibular tooth‑supported overdenture, visited the Prosthodontics Department of the Faculty of Dental Medicine of the University of Porto. The patient reported that the prosthesis had been installed 6 years earlier. Despite having changed the Teflon caps (female portions) embedded into the denture base recently, the retention and stability provided by the attachment system were minimal.

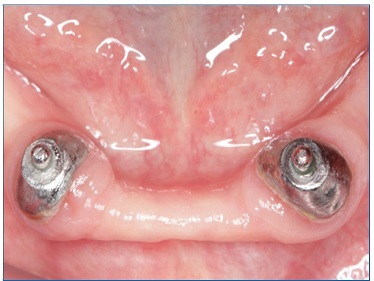

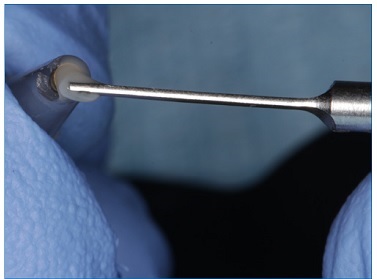

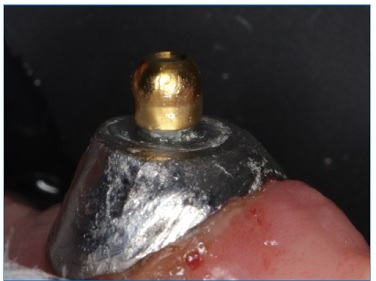

The patient’s mandible had two remaining teeth, the left and right canines, which were used as abutments for ball attachments cemented into the prepared roots (Figure 1). Clinical examination revealed wear of both attachments, with an evident loss of the ball‑shaped surface, thus explaining the impaired overdenture retention (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and radiographic examination, both abutments were considered healthy without signs of periodontal disease, apart from the presence of a 2 ‑ to 3 ‑ mm gingival recession at the vestibular area. Periodontal parameters, such as probing depth, mobility, bleeding index, calculus, and plaque index, were taken into account for this evaluation. The root canal treatment was as well considered satisfactory and stable. In terms of aesthetics, the patient was satisfied with the mandibular overdenture, and placing dental implants was not an option due to economic factors. The replacement of intraradicular posts supporting ball attachments has a high risk of root fracture during the disassembly phase. In line with this, it was decided that a Concave Reconstructive Sphere system (Rhein 83R, USA) would be used to restore the retention properties of the attachments.

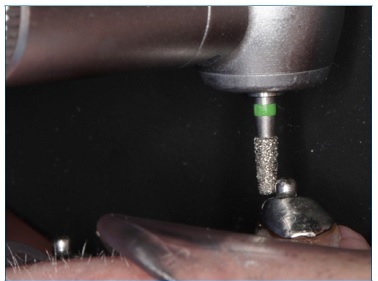

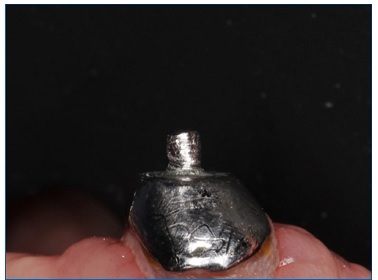

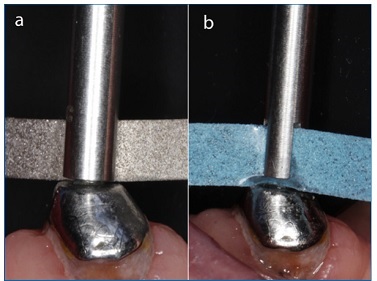

This system is indicated for worn spherical attachments that no longer provide an adequate retentive force. Firstly, the passive insertion of the concave sphere over the worn ball attachment was tested (Figure 3). After confirming the lack of passiveness, a taper rounded shoulder diamond bur was used to slightly reduce the diameter of the worn ball and allow a passive fit of the concave sphere (Figures 4 and 5). When the adequate fit of the concave sphere was achieved (Figure 6), two different diamond strips were placed on the sphere holder for final polishing of the old ball attachments (Figure 7a‑7d).

Figure 7 Two different diamond strips were placed on the sphere holder for final polishing of the prepared ball attachments. a) hard polishing strip; b) soft polishing strip

Afterward, a small amount of self‑curing modified glass‑ionomer cement (FujiCEM 2, GC Eurove N.V., Belgium) was placed inside the sphere (Figure 8) and over the previously prepared worn ball attachment. Once the curing process was completed, the excess of cement was carefully removed (Figure 9). After replacing the Teflon caps on the overdenture, rebasing of the denture was not considered necessary, and the retention of the attachment system was successfully restored. After checking occlusal contacts, the treatment was completed, and the patient discharged.

Figure 8 Placement of a self‑curing modified glass‑ionomer cement by using the sphere support to retain the sphere and the spatula instrument

Figure 9 Appearance of the intraradicular post and attachment after replacing the ball attachment with the concave system and removing the excess of cement

One year later, the patient was recalled for a follow‑ up (Figure 10), and the ball attachments restored with the concave reconstructive system still provided adequate retention and support for the mandibular overdenture, thus fulfilling the patients’ expectations.

Discussion and conclusions

Tooth‑supported overdenture is a simple and cost‑effective prosthetic treatment modality. By preserving the remaining natural teeth, this approach maintains dental proprioception and improves the distribution of masticatory forces, while also decreasing the rate of alveolar bone resorption and delaying complete edentulism, whose deleterious consequences, particularly in the mandible, are well known.9 In parallel, tooth attachments enhance the retention, support, and stability of removable dentures. The selection of strategic teeth or roots as abutments is pivotal for the success of an overdenture.

Tooth attachments are indicated in the following clinical situations: unfavorable crown‑to‑root ratio, presence of few remaining natural teeth, and patients with high surgical risks or contraindications.10 Tooth‑supported overdenture is still a well‑accepted treatment modality by both patients and dental clinicians. Moreover, the principles of this prosthodontics treatment have been adopted in overdentures supported by mini‑implants and implants as a strategy for completely edentulous patients.11

A variety of overdenture attachment systems are available. As a common feature, all attachments are designed to decrease the vertical movement of dentures and can be used isolated or splinted. Ball attachments are a reliable and simple retentive system option that allows appropriate retention and distribution of occlusal forces, while also acting as shock absorbers and stress redirectors. Bar attachments are also commonly used for overdentures since they provide a splinting mechanism between abutments.3,12

Despite their numerous advantages, removable overdentures require periodic maintenance and adjustments. In fact, the replacement and maintenance of ball attachments and O‑rings are common procedures. Regardless of the attachment design, a gradual loss of retention over time is inevitable due to the nature of the materials and the stress suffered during continuous insertion and disinsertion cycles.13,14

The concave reconstructive sphere system enabled the reshaping of worn attachments, thus representing a valuable solution for restoring their retentive force without removal of the intraradicular post, which would involve a high risk of root fracture, obviated with this conservative strategy. Moreover, the Teflon cap of the system fits into the standard Rhein83R stainless‑steel housings. The versatility of the procedure is another advantage. In fact, in the presence of limited space for the stainless‑steel housing, the Teflon cap may be directly rebased into the acrylic without the housing. It should be mentioned that increasing the ball attachment size reduces the amount of surrounding acrylic, which leads to thinner overdentures in the attachment area, with a higher risk of fracture.

In clinical cases similar to the one herein discussed, other oral rehabilitation procedures and treatment plans should be envisaged. For example, if the worn ball attachment were coupled with intraradicular post deterioration, removal of the posts would be inevitable, and new intraradicular posts and a new mandibular overdenture should be placed. Additionally, if both abutments were compromised and tooth extraction was indicated, retrieving the old overdenture would not be possible. In this scenario, other prosthodontic treatments should be discussed, such as a conventional mandibular removable denture, implant‑supported overdenture (with a minimum of two and a maximum of four implants) and/or a fixed full‑arch rehabilitation (with a minimum of four implants).10,15

The case report here described illustrates the clinical potential of the Concave Reconstructive Sphere system as a cost‑effective, in‑office, single‑visit, minimally invasive, versatile, and conservative procedure.