Introduction

The glandular odontogenic cyst (GOC) is a rare jaw development cyst. It was initially described by Padayachee and Van Wyk1 as a “sialo‑odontogenic cyst” due to the presence of glandular elements,2 and only in the following year when eight cases of this same lesion were reported, its currently used term was proposed.3,4In 1992, the World Health Organization (WHO) included GOC in its classification, describing it as “a cyst that originates in the dental support areas of the jawbones and is characterized by an epithelial lining with columnar or cuboidal cells, either on the surface or in its lining, with crypts or cyst‑like spaces within the epithelium thickness.”5,6 The last edition of the WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors, published in 2017, defines GOC as a development cyst with epithelial characteristics that simulate the salivary gland or glandular differentiation.7

On clinical examination, GOC presents as an asymptomatic slow‑growing swelling, affecting most commonly the anterior mandible region. It usually affects individuals between the 5th and 7th decades of life,2 with a slight predilection for males. Radiographic examinations reveal a radiolucent unilateral or multilocular intraosseous lesion with well‑defined margins, which may show cortical perforation and tooth displacement. However, clinical and radiographic characteristics are non‑specific and may mimic other destructive damage to the jawbones. Therefore, performing a biopsy is of great clinical importance to obtain a proper diagnosis and, consequently, begin treatment.8

Since GOCs are characterized by aggressive biological behavior and a high recurrence rate, the therapeutic approach is quite controversial, ranging from enucleation and curettage to en bloc resection, with the possibility of bone graft for immediate reconstruction.9 Therefore, the present study aims to present a clinical case of GOC with an emphasis on its clinical‑pathological characteristics, diagnosis, and clinical management.

Case report

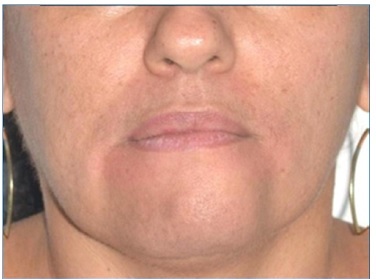

A 40‑year‑old black female patient attended the Buccomaxilofacial Surgery and Traumatology service of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Natal, RN, Brazil), with the chief complaint of painless swelling of the jaw for 6 months (Figure 1). Intraoral examination revealed a bluish‑colored swelling of the anterior mandible with a hardened consistency and approximately 4 cm in diameter, in the region of teeth 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3, which responded positively to the vitality test (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Initial extraoral clinical examination, in which a swollen chin region is observed from a frontal view of the patient

Figure 2 Physical intraoral examination, where a bluish‑colored lesion is observed in the anterior mandible surface

Mobility and increased periodontal probing depth were not observed. A panoramic radiograph revealed radiolucent and multilocular lesions associated with tooth displacement (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Panoramic radiograph indicating the presence of radiolucent and multilocular osteolytic lesions in the symphysis region and left mandibular body, with displacement of the roots of teeth 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3.

The patient was initially submitted to an aspiration puncture in the lesion, which confirmed its cystic nature. Then, we performed an incisional biopsy in the more exteriorized region of the lesion, evidenced by the bluish color in the mucosa. The dimensions of the tissue fragment removed were 3.3 x 2.0 x 0.3 cm. Odontogenic keratocyst and botryoid odontogenic cyst were considered as diagnostic hypotheses.

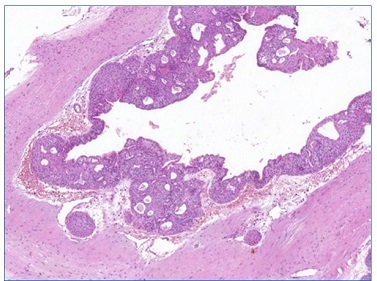

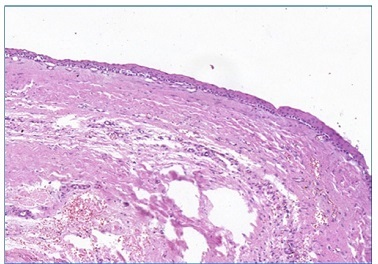

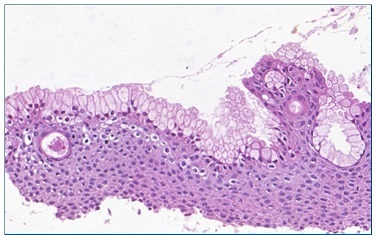

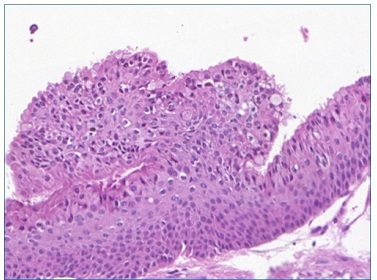

A histopathological examination revealed a pathological cavity lined with a non‑keratinized stratified squamous epithelium of varying thickness, with columnar and sometimes ciliated cells. Mucous cells and duct‑like microcystic spaces containing amorphous, mucus‑compatible eosinophilic material were also evidenced. Moreover, eosinophilic cuboidal or columnar cells (hobnail cells) were evidenced on the epithelir al lining surface. The capsule, composed of dense fibrous connective tissue, was adjacent to the cystic epithelium (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7). Thus, based on the clinical and microscopic findings, the histopathological diagnosis was GOC.

Figure 4 Odontogenic cystic lesion characterized by a pathological cavity lined by an epithelium with papillary projections to the lumen, in addition to the presence of various intraepithelial cystic spaces and “dimensions” of the epithelium (5x magnification) (Pannoramic Viewer; H / E)

Figure 5 Flat interface of the epithelial lining with the fibrous connective tissue capsule (10x magnification) (Pannoramic Viewer; H / E)

Figure 6 Numerous mucous cells without cystic epithelial lining (20x magnification) (Pannoramic Viewer; H / E)

Figure 7 Over the epithelial surface, eosinophilic cuboidal to columnar cells, consistent with hobnail cells, are evidenced (30x magnification) (Pannoramic Viewer; H / E)

Due to GOC’s high recurrence rate, the surgical plan consisted of lesion resection followed by immediate reconstruction.

A multi‑slice computed tomography was then requested for a detailed evaluation of the lesion and development of a prototype biomodel. Preoperative laboratory tests and surgical risk assessment were also requested.

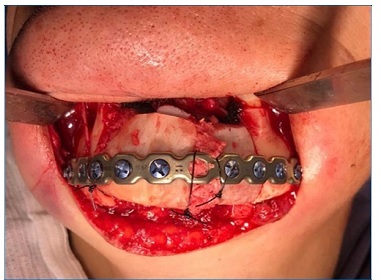

The lesion was resected with a safety margin (0.5 cm), generating a 4‑cm defect in the mandibular segment, followed by the fitting of a mandibular reconstruction plate (Figures 8, 9, 10).

Simultaneously, the medical team performed graft removal from the anterior iliac crest region, thus enabling subsequent preparation, adaptation, and fixation of the graft in the resected area, using 2.4‑mm system screws. Finally, muscle resuspension was performed on the plate, followed by access suture and compressive dressing application. The patient was under general anesthesia during the surgery. Prophylactic medication consisting of intravenous cephalothin (1 g), dexamethasone (10 mg), and dipyrone (1 g) was administered and maintained in the postoperative period with adequate doses. During the immediate postoperative period, the patient had no pain complaints and presented with edema compatible with the performed procedure and limited mouth opening.

The histopathological diagnosis was confirmed by the excisional biopsy, with free lesion margins. The patient has been under follow‑ up for 1 year, with no recurrences at the moment and good graft bone preservation (Figures 11 and 12).

Discussion and conclusions

This article highlights clinical, diagnostical, and therapeutic GOC aspects. Due to its aggressive biological behavior and high recurrence rate, studies and case reports that describe its occurrence are of significant clinical relevance, contributing to proper diagnosis and clinical management, as well as providing a broad view of the surgical techniques that may be adopted.

With an estimated prevalence of 0.17% of all gnathic cysts,10 GOC is a rare but relatively well‑known entity with well‑described microscopic characteristics. Clinically, GOC tends to affect most commonly the mandible, especially its anterior region, followed by the anterior maxilla.11 In most cases, cortical expansion is observed, with or without cortical perforation, as well as root resorption and tooth displacement, which indicate the aggressiveness potential of this type of lesion.8 Despite presenting non‑specific radiographic characteristics, most cases present as multilocular lesions.11 In the present report, the anterior mandible had a radiolucent and multilocular radiographic appearance associated with radicular dislocation.

Regarding histopathological aspects, microscopic characteristics are categorized into major and minor criteria.12 Major criteria must be present for diagnosis, while smaller criteria are favorable for diagnosis but not mandatory.13 However, there is still no consensus on how many criteria would be required for the diagnosis. In a multicenter retrospective study, all cases analyzed exhibited eosinophilic cuboid cells (hobnail), a non‑specific feature required for GOC diagnosis. In addition, those authors reported that some of the most useful microscopic features that distinguish GOC from other lesions that may mimic it are [1] microcysts; [2] epithelial spheres; [3] clear cells; [4] variable thickness of the epithelial cyst lining; and [5] multiple compartments.2 Thus, the present case is highly predictive of GOC, as all aforementioned characteristics were present, in addition to the presence of ciliate and mucous cells.

GOC may exhibit morphological similarities to other cystic jaw lesions, such as dentigerous cysts displaying metaplastic changes, ciliated surgical cysts, lateral periodontal cysts, root cysts, residual cysts with mucous metaplasia, and botryoid odontogenic cysts.8,2 The low‑grade variant of the central mucoepidermoid carcinoma should also be considered a differential GOC diagnosis since these lesions share certain histopathological features, such as the presence of clear and mucous cells and mucin‑filled cystic spaces.7,11In addition, in rare cases, GOC may contain small islands in the cystic wall that resemble mucoepidermoid carcinoma. This microscopic aspect suggests that GOC and central mucoepidermoid carcinoma may share a histopathological spectrum, although it is unknown whether this finding is associated with more aggressive or malignant behavior.2

Histochemical and immunohistochemical techniques may be used as adjunctive tools to histological and morphological features to obtain an accurate diagnosis. Special stains, such as mucicarmine and periodic acid‑Schiff (PAS), are used to confirm the presence of mucin in the lesion. Also, immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin 19 (CK19) reveals strong, homogeneous positivity in all the epithelium layers, which confirms its odontogenic nature.11,14The expression of cytokeratins has been reported to differ between GOCs and central mucoepidermoid carcinoma, suggesting that CK18 and CK19 could help distinguish these two entities.15

As is well‑known, GOC exhibits an unpredictable and aggressive clinical behavior associated with a high incidence of cortical perforation and a relatively high recurrence rate, directly related to lesion size.4,11 The literature reports a preference for more conservative therapeutic approaches, such as enucleation, curettage, excision, cystectomy, and peripheral ostectomy.8,2However, a study showed that cases treated by radical surgical procedures did not recur, while 35.9% of conservatively treated cases did.8 Enucleation and curettage are most associated with a higher risk of recurrence, especially in large and multilocular lesions. In these situations, it is preferable to adopt more aggressive therapeutic measures, in addition to long‑term patient follow‑up.

The use of adjuvant methods such as peripheral osteotomy or marginal resection is associated with a significant reduction in lesion recurrence.12,8,11 In the present case, a more radical therapeutic approach was adopted with segmental resection followed by immediate reconstruction to reduce the lesion recurrence risks. After one year of lesion excision, the patient has no signs of relapse. Nevertheless, a long‑term follow‑up of the patient is still required to keep up with a possible recurrence.

Due to its rarity, performing controlled studies comparing different GOC therapeutic approaches is difficult. A clear definition of histopathological criteria is essential to aid with the diagnosis, as well as searches for specific markers that support the diagnosis. Histochemical (mucicarmine and PAS) and immunohistochemical (CK‑19) techniques may be useful tools to verify unclear cases, especially to differentiate from central mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Thus, greater diagnostic accuracy contributes to the adoption of appropriate personalized therapeutic measures.