Introduction

Dental caries is a dental hard‑tissue disease of multifactorial etiology that is strongly related to sugar fermentation by bacteria present in the oral cavity, mainly streptococci and lactobacilli.1 Ninety percent of dental caries occur in the occlusal surfaces of the posterior teeth’ pits,2 where it is easier for the bacteria to build up.3

Dental sealants are the most common method to prevent dental caries on teeth’ occlusal surfaces by creating a protective barrier on pits and fissures, therefore preventing the accumulation of bacteria responsible for the cariogenic process.4

Despite the many studies supporting the use of dental sealants in non‑cavitated occlusal surfaces of children, adolescents, and young adults,5 in many countries, like Spain,2,6Greece,7,8Sweden,9 Scotland,10 and the United States of America,11 this preventive method is little used. In Portugal, dental sealants were introduced in the late ‘90s, but only in 1999 did the Portuguese General Directorate of Health (Direcao Geral de Saude - DGS) release the first normative document to regulate the use of this technique.12

The National Oral Health Promotion Program (Programa Nacional de Promocao de Saude Oral - PNPSO), implemented mostly by dental hygienists at health centers throughout Portugal, focuses mainly on reducing the incidence and prevalence of oral diseases in several population groups.13Aiming to prevent dental caries in children and teenagers, the PNPSO established public‑ private partnerships to allow free oral health appointments for applying dental sealants.12,14Even though these partnerships exist, several studies show that dental sealants are little used in Portugal15,16 and that there is still a long way to go before accomplishing the goal established by the World Health Organization (WHO) of having 80% of the 6‑year‑old children in the European Union caries‑free.

Within a multidisciplinary work team, the dental hygienist has the highest responsibility to fight and prevent dental caries since their job focuses on preventing and stopping oral diseases and promoting oral health.17 Therefore, the perception of dental hygienists regarding dental sealants should be assessed to settle which changes can and should be done to optimize the population’s oral health.6

Attitudes and behaviors can affect the professional practice of dental hygienists. This study assembles an evaluation of their attitudes, defined as favorable or unfavorable provisions, and behaviors, defined as the tendency to act consistently with the attitude, concerning dental sealants. Moreover, the values concerning dental sealants’ use were also evaluated to help predict clinical practice.6 By linking these three previously mentioned factors with the opinions about dental sealants, it is possible to estimate the dental hygienists’ willingness to use them and assess what can be changed to promote dental caries prevention.

This study aims to characterize the sample of responders and present the data obtained from the evaluation on the

Material and methods

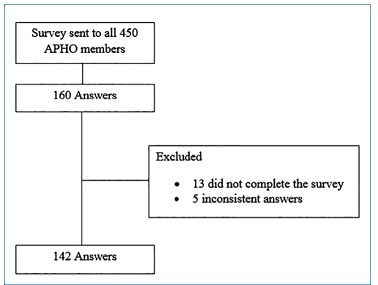

An observational cross‑sectional study was conducted from December 2018 to June 2019 in dental hygienists from Portugal who were members of the Portuguese Association of Dental Hygienists (APHO). A non‑probabilistic sample was obtained by emailing a survey to all contacts of APHO. The survey was sent twice, with a one‑month interval, to increase the number of answers and, consequently, the sample size. One hundred and sixty members answered the survey, but 13 did not complete it, and five gave inconsistent answers. These 18 respondents were excluded from the study. The final sample was composed of 142 Portuguese dental hygienists (Figure 1).

The study authors translated to Portuguese and culturally adapted to Portugal a Spanish KOVP questionnaire2 to evaluate the dental hygienists’ KOVP regarding dental sealants. Two experts in the area verified the adapted survey. Facial validity was checked by three dental hygiene and dentistry students from the Faculty of Dental Medicine of the University of Lisbon.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first one had 31 five‑point Likert‑scale statements (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to evaluate KOVP organized in four categories. The second part had four questions on the respondents’ demographics by the following metrics: sex, years of experience (≤ 3 years, 4‑15 years, ≥ 16 years), place of work (urban, suburban, both), and sector of work (public, private, both). By submitting their answers, all participants agreed with the terms and conditions of this study.

For the statistical analysis, the IBM SPSS 25 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) was used to determine frequency distribution, mean, and standard deviation of the Likert scale for each of the 31 survey statements and each of the four assessment domains (knowledge, opinion, values, and practice). The Wilcoxon matched‑pairs signed‑ranks test, the Mann‑Whitney test, the Kruskal‑Wallis test, the Spearman’s correlation, and the V‑Cramer test were used for data analysis. All data were analyzed with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

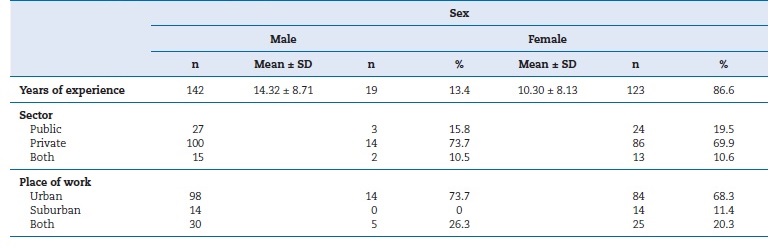

A sample of 142 Portuguese dental hygienists, 86.6% female (n=123) and 13.4% male (n=19), participated in this study. The mean (± SD) years of experience were 10.84 ± 8.3 (range 1‑32).

Regarding practice location, 69.0% (n=98) worked in urban regions, 9.9% (n=14) in suburban regions, and 21.1% (n=30) in both. (Table 1)

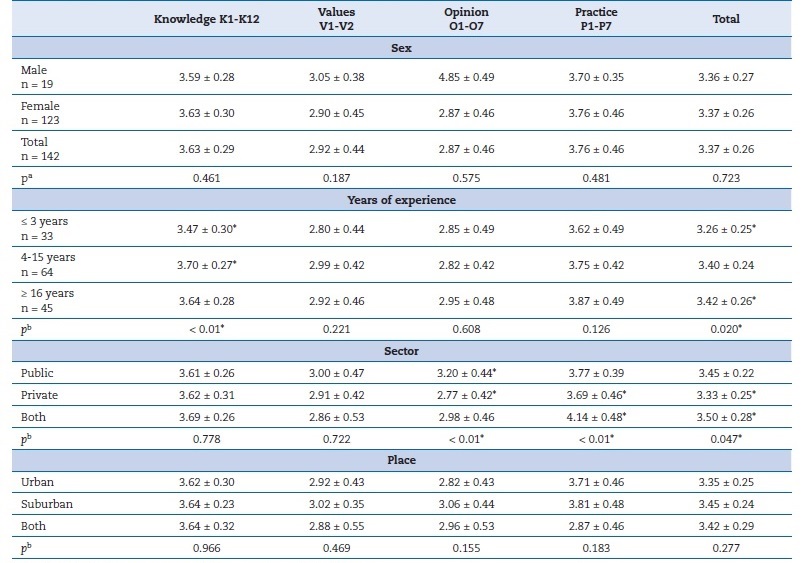

The KOVP groups’ (four groups: knowledge, opinion, value, and practice) results were analyzed and then associated with demographics (namely, sex, years of experience, sector of work, and place of work). The KOVP results, on a scale of 0 to 5, were as follows: knowledge = 3.63 ± 0.29; value = 2.92 ± 0.44; opinion = 2.87 ± 0.42; and practice = 3.76 ± 0.46. The four KOVP statements were associated with the demographics, generating 16 metrics that ranged from 2.80 to 4.14 (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), indicating a positive impression of dental sealants.

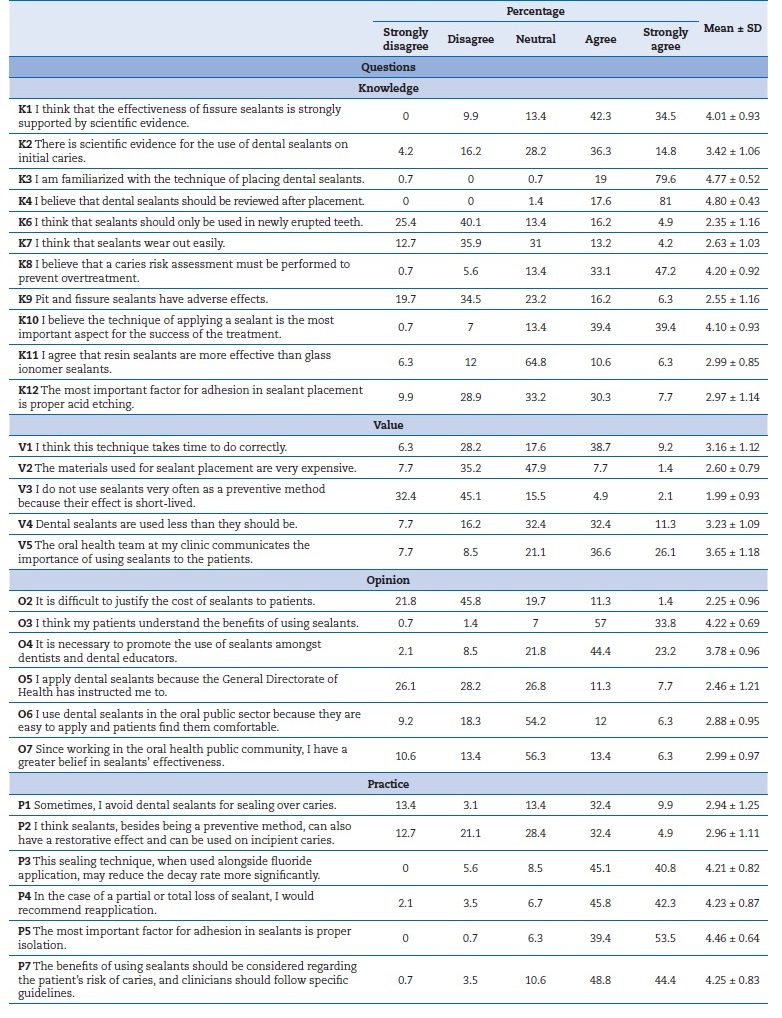

Table 2 shows that 98.6% of dental hygienists were familiarized with the technique of pit and fissure sealants and believed they should be evaluated after placement. In total, 9.1% of the respondents stated that materials used for placing sealants were very expensive, and 7% that their effect was not long‑lasting. A total of 12.7% of dental hygienists found it difficult to justify the costs of sealants to patients, and 67.6% thought the use of sealants should be promoted among dentists and dental hygienists.

Table 3 shows a statistically significant difference when comparing knowledge between years of experience. The group of 4-15 years of experience (3.70 ± 0.27) presented better scores on knowledge than the group with ≤3 years of experience (3.47 ± 0.30) (p<0.01).

When comparing opinions between sectors of work, workers in public clinics (3.20 ± 0.44) had a better opinion on dental sealants than those in private clinics (2.77 ± 0.42) (p<0.01). Also, professionals working in both public and private clinics (4.14 ± 0.48) had higher scores for opinion than those working only in private clinics (3.69 ± 0.46) (p<0.01).

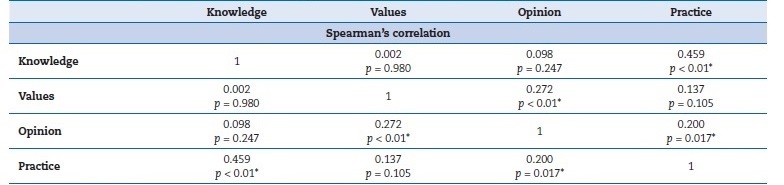

Table 4 shows the correlation between knowledge, opinion, values, and practice. A moderate positive linear correlation between knowledge and practice was found (p<0.01), and the other variables showed weak positive linear correlations among themselves (p>0.05). There was no negative correlation between the variables.

Discussion

The lack of previous similar studies in Portugal regarding oral health professionals’ KOVP on dental sealants does not allow for comparisons. However, this study was based on a prior one done in Spain,2 allowing a comparison between two neighboring countries.

This study’s findings show that Portuguese dental hygienists have a positive KOVP regarding pit and fissure sealants. The statistical findings for KOVP associated with the demographics showed that knowledge was significantly associated with years of experience. Dental hygienists with 4‑15 years of experience obtained significantly better scores on knowledge than those with ≤3 years of experience. This finding results from more years of experience enhancing practice, which improves knowledge. On the other hand, the data from the Spanish study2 showed that fewer years of experience assured better scores on knowledge; yet, this was not evidence‑based knowledge but instead research knowledge obtained during the professionals’ studies. Accordingly, several studies show that some countries also lack professional/ personal evidence‑based knowledge. A study from 2010 conducted in the USA indicated that dentists used dental sealants as a preventive routine but had poor evidence‑based knowledge.11 A more recent study from 2018 indicated that dental students in India had enough knowledge about pit and fissure sealants but lacked evidence‑ based knowledge about this practice.18

This multivariate analysis from Portugal found statistical differences when comparing sectors of clinical practice regarding practice. However, this was not detected in Spain,2

where all dental hygienists, regardless of where they worked, had similar scores on practice. Both studies showed significant differences when associating the sector of clinical practice with opinions. While Portuguese data showed that opinions were higher in professionals working in public clinics than those working in private ones, Spanish data2 showed that professionals working in both sectors of clinics were the ones with the highest scores on opinions. Studies that evaluate models for behavior change suggest that legal and economic issues affect changes in the sector of clinical practice greatly.10,19 This rationale may explain why Portuguese dental hygienists working in public clinics, where the state covers the sealants’ expense without affecting their salary, have significantly higher opinion scores than those working in private clinics. In private clinics, some workers might be influenced to not apply as many sealants as they should because the clinic has to support the costs of the treatment or because their salary might change depending on the treatments given, therefore opting for other techniques that may benefit their income.

The positive linear correlation between knowledge and practice found can be important for future decisions by the government to apply more measures to improve the use of dental sealants, as it is already known that, by stimulating the knowledge of this technique, we will have more positive practice.

When comparing the data obtained in this study with the data obtained in a previous study in Spain,2 Portuguese dental hygienists’ results tended to be better: Spanish dental hygienists had neutral‑to‑positive feelings and lower scores in all four categories (knowledge = 3.57 ± 0.41; value = 2.58 ± 0.77; opinion = 2.17 ± 0.42; practice = 3.56 ± 0.46).

This study’s practice score indicates that Portuguese dental hygienists have good practices regarding dental sealants, which are better than in other countries. In Spain, a study to evaluate the dentists’ KOVP showed that these professionals were aware of the effectiveness and had neutral‑to‑positive impressions of dental sealants but underused them.6 Two studies from 2010 and 2011 conducted in Greece indicated that dentists in this country believed in and applied prevention measures, but only 1/3 of them used fissure sealants in their clinical practice, indicating a low use of dental sealants.7,8

This study’s sample represents a limitation. This non‑probabilistic sample of 142 dental hygienists from a population of approximately 520 active dental hygienists in Portugal

(27.3% of dental hygienists) compromises its external validity and limits the extrapolation of data to all dental hygienists in Portugal. Also, the fact that the survey was sent by email may have limited the number of responses, as it was only available to those with Internet access.

Conclusions

Portuguese dental hygienists have positive ideas, good knowledge, and good practices regarding dental sealants. Dental hygienists working in public clinics have better opinions about dental sealants, probably due to the national oral health program’s support in terms of costs. There is a positive correlation between knowledge and practice, meaning that when one is enhanced, the other will also improve, and this can be used to further increase the use of dental sealants in Portugal.