Introduction

The number of children with microcephaly has been increasing in Brazil. Between 2000-2014, 164 cases were notified, while in 2015, it escalated to 1,608 cases.1 After the Zika epidemic, countless newborns with microcephaly further developed the “congenital Zika syndrome,” characterized by severe developmental delay, intellectual and visual impairment, musculoskeletal abnormalities, and epilepsy.2 The etiology of microcephaly is complex and multifactorial, as it can occur due to chromosomal abnormalities, exposure to environmental teratogens, metabolic diseases, or infectious processes during pregnancy.1,3Also, based on the research available to date, another cause of microcephaly has been the Zika virus (ZIKV). Microcephaly is diagnosed after birth when the head circumference measures less than 32 cm - value considered ideal.1,3

Patients with microcephaly may have multiple associated oral conditions,5,6 including eruption cyst (EC), defined as a liquid cavity originating from dental epithelial tissues.7 EC is a benign pathology, usually asymptomatic, that happens in a retained, impacted, non-erupted tooth or a tooth with late eruption, adjacent to the dental crown at the cementoenamel junction.7,8The exact etiology of this lesion is unknown; however, some factors are thought to contribute to its development, like trauma, lack of space for tooth eruption, and excessive fibrous tissue in the eruption region.8,9

Patients with microcephaly due to maternal ZIKV infection manifest several comorbidities that further aggravate the patient’s systemic condition, so adequate planning for these patients’ treatment is crucial and must be performed by assessing behavioral, systemic, and local issues.2-4 This study aimed to report the clinical case of a patient with microcephaly due to maternal ZIKV infection who had multiple ECs in the region of the primary molars, and discuss the literature-based treatment adopted.

Case report

A 3-year and 7-month-old male child with multiple ECs, accompanied by his mother, visited the clinic of the Specialization Course in Dentistry for Patients with Special Needs of the Brazilian Dental Association (ABO, Associação Brasileira de Odontologia), Sergipe region. During anamnesis, the mother reported that she had been diagnosed through clinical examination with ZIKV infection during pregnancy. The patient had a medical diagnosis of microcephaly, with recurrent pulmonary infection episodes associated with bronchospasm attacks, due to aspiration syndrome and physical disability. The mother reported that, despite taking anticonvulsant medication, her child still had recurrent seizures, which caused her to take him to the emergency department whenever the seizure events persisted for a relatively longer time.

Upon clinical examination, we noticed that the child was exclusively fed through a gastric probe after gastrostomy tube feeding (GTF). In addition, he had not developed a handgrip, used lower-limb movements to express his needs, showed no head and neck support, could not speak, did not walk, and was in a children’s wheelchair.

Intraoral examination revealed a circumscribed floating swelling on the gingival mucosa that was as pink as the adjacent oral mucosa and floated on palpation due to liquid content.

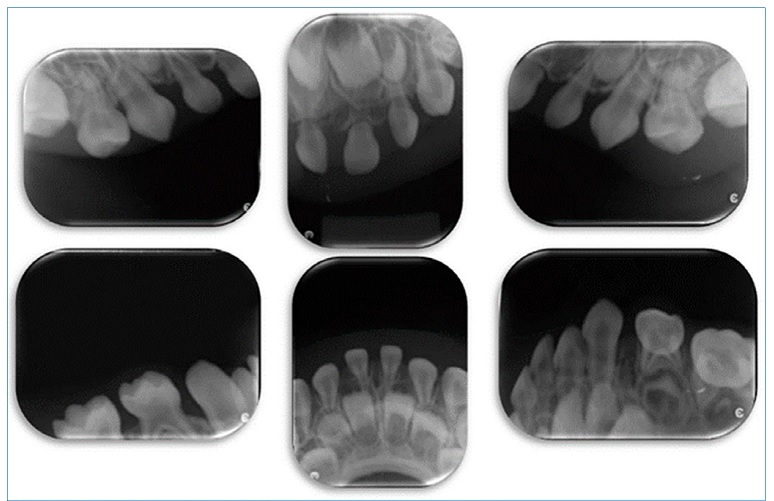

It was located in the region of the primary maxillary and mandibular molars and was compatible with the diagnosis of EC (Figure 1). During the examination, we also verified that his oral health was good, without gingival inflammation, and he had all anterior upper and lower teeth. He had an anterior open bite, lingual interposition with atypical swallowing, lack of lip sealing with lingual hypotonia, sialorrhea at rest (Figures 2, 3, and 4), and difficulty swallowing saliva, with reports of frequent choking. To complement the clinical examination, establish the final diagnosis, and plan the case, we requested periapical radiographs, which revealed the presence of primary unerupted teeth (Figure 5).

After EC diagnosis, the mother was informed of the need for intervention in the ambulatory surgery center, under general anesthesia due to the non-cooperation and great systemic aggravation of the patient, to perform incision and drainage of the cystic content, exposing the occlusal surfaces of the teeth involved with ECs to the oral environment. The patient underwent all preoperative exams for admission and treatment in the operating room. Three dates were scheduled, but the mother canceled the surgical procedure every time 24 hours earlier, justifying that the patient had flu or pneumonia.

After four months of attempting to reschedule the surgical procedure dates, the patient attended a return appointment at the specialized outpatient clinic for reassessment.

We observed that seven of his eight ECs had ruptured, with complete regression of the initial lesion and consequent spontaneous tooth eruption, thus deeming the surgical intervention unnecessary. The only EC remaining was related to tooth 65 (Figure 6).

Thus, the team of professionals involved in the case consensually decided to wait and monitor the rupture of the last EC. We instructed the mother to massage the lesion area using a silicone finger protector or gauze and use teethers to favor a spontaneous regression and physiological eruption of the tooth. These indications were due to the patient not being orally fed and, thus, not chewing, which could be the cause of the delayed rupture of ECs, with delayed dental eruption.

Discussion and conclusions

In most cases, microcephaly is associated with other congenital disorders relevant to dental practice, such as swallowing problems, intellectual disability, or epilepsy.(10) Caregivers should have basic knowledge of oral hygiene in order to reduce oral diseases. Dental surgeons must demonstrate oral hygiene techniques and schedule periodic dental consultations.4,11

The EC has been considered a form of dentigerous cyst that occurs in the mucosa overlying the teeth just before their eruption.7 Clinically, it is characterized by the presence of translucent or purplish swelling over the tooth crown.7-9It may be present unilaterally and, less frequently, bilaterally.8,9,12Very rarely, it can be found bilaterally and in both arches,13,14as in the case reported here. A study on 53 patients with 66 ECs reported that most patients (46 cases, 86.8%) did not receive treatment and had their ECs spontaneously subsided; surgical treatment was provided in the remaining seven cases (13.2).

Therefore, the recommended treatment is close monitoring with follow-up throughout the eruptive process of the involved teeth.8

The current published literature points out that EC can occur in different age groups, i.e., during the normal period of eruption of primary12,14or permanent teeth, and is more common in boys.7 Delayed eruption in patients with microcephaly has been previously observed,5,6as in this case, where a 3-year and 7-month-old patient had not yet had primary molars.

However, no cases of EC and microcephaly have been found in the literature.

Regarding EC’s diagnosis, clinical and radiographic evaluation, aspiration, and biopsy7 are indicated. In this case, only clinical and radiographic examination was performed due to the difficulty in holding the patient steady, which made surgical intervention for biopsy and aspiration of the internal fluid impossible, as seen in other cases in the literature that opted to monitor the lesion without performing histopathological analysis.8,12

Endoscopic GTF is indicated for children with feeding difficulties, especially when caused by neurological impairments.15 Accordingly, our reported case was fed exclusively through an enteral feeding tube. The lack of oral chewing during feeding may have delayed the spontaneous disappearance of ECs.

The literature recommends two EC treatment approaches: a more conservative one, with EC monitoring until it disappears spontaneously with teeth eruption;8,12and surgical treatment with excisional biopsy13,14or drainage of the cystic fluid.9 In the present study, surgical intervention under general anesthesia in a hospital environment was initially decided based on another case13 since the patient was very young, showed little cooperation, and had multiple ECs, with consequent irritation and discomfort, as reported by the mother.

Moreover, considering that the patient presented a highly compromised systemic condition, we initially decided on surgical intervention in the hospital to have more reliable means to generally monitor the patient during the performance of a single intervention.

Due to complications to perform the planned surgical intervention under general anesthesia, by the time of the return appointment, most ECs had regressed with the eruption of primary molars, except for the cyst in tooth 65’s region. Thus, we decided to wait and monitor the tooth-eruption process, as it is known that tooth eruption delay is common in patients with microcephaly.5,6

When an EC is present, the dentist must have extensive knowledge and ability to advise that this type of lesion is benign, and a less invasive approach may be adopted in asymptomatic cases and small injuries by monitoring the spontaneous resolution of the cyst without the need of surgical intervention. Therefore, treatments should be decided on a case basis, with adequate analysis of clinical conditions and radiographic findings, especially when dealing with disabled children, whose systemic condition can be complex due to several comorbidities. Knowing that infants with microcephaly may have delayed tooth eruption, the spontaneous resolution of ECs may take longer to resolve itself.