Introduction

The odontogenic keratocyst (OK) is a developmental odontogenic cyst whose nomenclature has been changing in recent decades. The 2005 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of Head and Neck Tumors reclassified the odontogenic keratocyst as a benign neoplasm, recommending the term “keratocystic odontogenic tumor” due to its aggressiveness, high recurrence rate, and association with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and mutations in the PTCH1 gene. However, in 2017, the WHO reclassified it as a cyst, alleging that mutations in the PTCH gene can occur even in non‑neoplastic lesions, such as the dentigerous cyst;1 besides, many researchers have suggested that cyst resolution after marsupialization is not compatible with a neoplastic process.1,2,3,4,5

OKs derive from the dental lamina and have a predilection for males, occurring mainly in the third decade of life.6‑9 The mandible is more affected than the maxilla, and the sites of predilection are its posterior body, angle, and ascending ramus.6,9The lesion is asymptomatic and is often diagnosed on routine radiographs. Thus, the general dentist’s attention while evaluating the maxillomandibular complex is essential and should not be limited to analyzing the teeth.10 OKs extend initially in the anteroposterior direction, causing expansion in a late stage.7,8In advanced stages, pain, edema, tooth displacement, root resorption, and pathologic fractures can be observed.8,9

Radiographically, the OK presents as a unior multilocular lesion, with often scalloped margins, commonly associated with impacted third molars.7,11Its differential diagnosis should include dentigerous cyst, ameloblastoma, radicular cyst, lateral periodontal cyst, and nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome.9

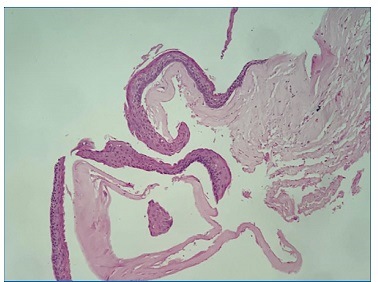

Histologically, OKs usually present a very thin and uniform lining epithelium and a well‑defined basal cell layer in a palisaded arrangement. The keratin layer is corrugated, and the cystic wall is thin and generally uninflamed; cell proliferation markers such as Ki‑7 and P53 can be observed.7,9,11The presence of satellite cysts potentially increases the chance of recurrence if they are not completely removed during surgery.8

Various treatment modalities have been reported, including marsupialization, enucleation with or without adjuvants, decompression, cryotherapy, and resection.6,8,9,11‑13 The goal is to choose the treatment modality that carries the lowest possible risk of recurrence and the least morbidity while still eradicating the lesion. The lesion recurrence rates vary according to the chosen treatment modality, with the lowest index associated with surgical resection. Due to its high morbidity, more conservative techniques are constantly used. Among them, enucleation associated with Carnoy’s solution has the lowest recurrence rate, being a good alternative to resection.8,13

The present study aimed to report a case of a large keratocyst with more than 14 years of evolution in a 67‑year‑old male patient that had not been diagnosed in three previous different panoramic radiographs and was treated with enucleation followed by the application of Carnoy’s solution.

Case report

A 67‑year‑old male patient was referred to our clinic to evaluate a mass on his face that had been gradually enlarging for the last five months. Past family and medical history were unremarkable. The patient reported discomfort at his mandible’s left posterior body for more than ten years. In the past, he had his impacted lower third molar removed after being told the discomfort was due to the tooth. However, the symptom persisted after the surgery, and he also started feeling a bad taste and sometimes could see a white/yellow liquid discharging from the area of the third molar. These symptoms persisted for a long time after the surgery, and he could not remember for how long exactly.

General physical examination showed an asymptomatic firm mass on the left preauricular area, covered with normal skin (Figure 1). The intraoral examination did not reveal any abnormality.

The patient presented his 2003, 2004, and 2013 panoramic radiographs, requested by different professionals, revealing the evolution of a large radiolucent lesion in the left posterior ascending ramus (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The patient stated that the lesion was never mentioned and, on two occasions, had received an antibiotic prescription alleging his discomfort was due to the third molar removal.

Figure 2 Panoramic radiography performed in 2003, showing an extensive radiolucent lesion in the left mandibular ramus (red arrow).

Figure 3 Panoramic radiography performed in 2004 after removal of the lower third molar, showing the lesion’s persistence.

Figure 4 Panoramic radiography performed in 2013, showing new bone formation in the 38 region and persistent lesion in the ramus.

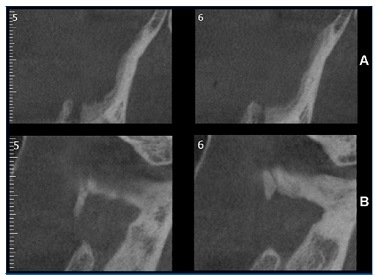

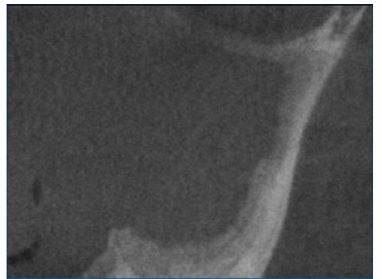

A panoramic radiograph and cone‑beam tomography were requested and revealed an extensive radiolucent lesion extending from the retromolar area to the mandibular incisure, causing an expansion of the anterior border of the ramus and perforation of the cortical bone (Figures 5 and 6). A routine blood examination showed nothing abnormal. Based on clinical and radiologic aspects, the initial diagnosis was keratocyst or ameloblastoma, and surgical treatment was indicated after establishing the final diagnosis.

Figure 5 Panoramic radiography performed after the initial consultation (2017), showing an increase in the lesion, with the expansion of the anterior border of the ramus.

Figure 6 Cone‑beam tomography showing an extensive hypodense image extending from the retromolar region to the mandibular notch.

An incisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia. After the mucoperiosteal flap was raised, a discharge of a whitish pasty material, suggestive of keratin, was observed. The anatomopathological examination confirmed the initial diagnosis of keratocyst (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Thin cystic lesion lining epithelium with a hyperchromatic basal layer in palisade and corrugated parakeratin layer.

The patient was informed about all treatment modalities and the recurrence rates associated with each one. Although partial resection with the placement of a customized prosthesis was recommended, he opted for a more conservative treatment, with enucleation followed by the application of Carnoy’s solution.

An incision was made, under general anesthesia, on the anterior border of the ramus, extending to the second premolar area. The mucoperiosteal flap was raised, followed by complete enucleation of the lesion. Then, the bone cavity was coated with gauze, and the Carnoy’s solution was applied for 3 minutes, followed by saline irrigation; this procedure was repeated three times. The wound was closed with absorbable suture, and the healing was uneventful. The patient was discharged from the hospital 24 hours later, with no pain complaints but mentioning lower lip cushioning.

In a seven‑day postoperative examination, he had good local healing and reported improvement of the cushioning. Complete resolution of paresthesia occurred around 40 days after surgery. The patient remains in semiannual radiographic control (Figures 8 and 9) and 18‑month cone‑beam tomography control. He shows significant bone neoformation compared to the initial tomography, with no signs of recurrence (Figure 10).

Figure 9 18‑month panoramic radiograph follow‑up showing significative bone neoformation with no signs of recurrence.

Discussion and conclusions

Early diagnosis of OK is the best way to avoid extensive bone destruction and more aggressive surgery. Unfortunately, in this case, despite the large radiolucent area in the mandibular ramus, three different professionals missed it. This overlook calls attention to the fact that some dentists look for alterations only in the teeth without analyzing all the anatomic structures in a panoramic radiograph.

Many accepted methods are used in the treatment of OKs, and the greatest challenge is to completely remove the cystic capsule, which is thin and friable. More conservative modalities include marsupialization, enucleation with or without adjuvants, such as ostectomy or Carnoy’s solution, and decompression followed by enucleation. Marsupialization and decompression are increasingly popular treatment options for OKs to preserve adjacent structures until sufficient ossification occurs.3 However, although these treatment modalities may decrease the cyst’s size, they do not definitively treat the OK, and additional surgical intervention is generally required for its removal.14 Besides, they require regular follow‑up visits, irrigation of the cyst cavity, and repeated adjustment of the stent.3

The most extensive OK treatment is osseous resection, which has the lowest recurrence rate. However, it causes considerable morbidity, particularly because reconstructive measures are necessary to restore jaw function and esthetics.6,8,11,14

In the present case, the patient rejected resection because he preferred to have a slightly higher risk of recurrence than undergo such an aggressive and mutilating treatment for a benign lesion.

Carnoy’s solution, the adjuvant of choice in the present case, is composed of ethanol, chloroform, glacial acetic acid, and ferric chloride.6 Enucleation associated with Carnoy’s solution showed good results in a previous study by Leung et al.,13 where its recurrence rate was 11.4%, with minimal morbidity.

A similar rate, 11.5%, was found by Al‑Moraissi et al.,15 who considered this method the primary treatment for OKs. Dashow et al.,16 however, obtained a significantly lower recurrence rate, 4.8%, pointing it as the lowest recurrence among conservative treatments. Chrcanovic and Gomez11 obtained a similar result, 5.3%, and considered it the lowest recurrence among the treatment modalities. Ribeiro‑Junior et al.2 concluded that Carnoy’s solution and peripheral ostectomy had similar efficacy in OK management. On the other hand, Karaca et al.6 compared the two modalities and concluded that peripheral ostectomy had a statistically higher recurrence than Carnoy’s solution, around 18.2% versus only 5.3%, respectively. In the present case, peripheral ostectomy was not considered a treatment option in order not to fragilize the mandible even more.

Carnoy’s solution is a chemical cauterization agent that was first used as a fixative agent in histology but has been used in the treatment of injuries due to its power to penetrate tissues, local fixation, and ability to promote hemostasis.14 It causes superficial tissue necrosis, from a chemical cauterization up to 1.5‑mm deep after 5 minutes of application in bone stores, and eliminates tumor cells.13,17 Its application method consists of protecting neighboring tissues with sterile gauze, coating the bone cavity with gauze, and applying the solution for 3 minutes, followed by irrigation with a saline solution. This procedure, repeated three times, was the same performed in our clinical case.13 Some authors believe that the use of Carnoy ´s solution after enucleation in areas of bone fenestration may help eliminate residual microcysts on the overlying soft tissue, and its effects may be superior compared to using curettage or peripheral ostectomy as the adjunctive procedure.9

In 1992, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited the use of chloroform in the composition of Carnoy due to being a carcinogen, and the modified Carnoy solution was then created.14,1 6,17The 3 ml of chloroform were replaced by 3 ml of absolute alcohol. However, studies’ results support the relevance of maintaining chloroform in the solution due to the lower rates of recurrence and better performance of the solution compared to the solution modified by removing chloroform.13,17 A recent study16 of 80 patients, where 44 were treated with Carnoy and 36 with modified Carnoy, concluded that recurrence was greater in patients treated with the modified solution, around 35% versus 10% with the original solution. This finding indicates that the original solution may still have a role in OK treatment as an adjunctive to enucleation, reducing recurrence.13 A survey with 809 dental surgeons in the United States revealed that 56% use the solution with chloroform and 42% without it; 27% reported having ceased to use it due to its unavailability in the market.14

Despite the good results presented in numerous researches with Carnoy’s solution, one study showed disadvantages of its use: as it is a caustic solution, it can cause toxicity to the adjacent soft tissues, skin, and dental follicles if the patient is a child. Moreover, the authors pointed out the impossibility of immediate bone grafting.7

Long follow‑up periods are suggested for this lesion because recurrence can occur up to 10 years after the initial treatment.7

It is recommended to reassess the patient every 6 months, as has been done in the present case. An early diagnosis of recurrence can be treated with conservative approaches.12

As OK is an asymptomatic lesion in its early stages, it is essential that the general dentist pays attention during radiographic evaluations, carefully observing all the bone structures and not just the teeth. Early diagnosis is important so that more conservative surgical treatments can be performed. In the present case, despite the advanced stage of bone destruction, enucleation associated with Carnoy’s solution has proved to be quite effective so far. Long‑term radiographic follow‑up is mandatory to establish how successful this treatment really was.