Introduction

Whiter teeth have been associated with a perception of beauty, health, and fitness. Thus, tooth color is considered one of the most important components in smile evaluation and facial esthetics, and tooth bleaching techniques have gained a major clinical relevance.1,2

Nowadays, tooth bleaching products usually have peroxide-releasing agents, such as hydrogen peroxide (HP) or carbamide peroxide.3,4 In fact, initially, HP percentages were commonly high. However, peroxide-releasing agents have known adverse effects on biological tissues that can increase with higher concentrations.3,5 For this reason, manufacturers and clinicians searched for effective techniques with low HP concentrations, which resulted in the nightguard vital bleaching technique gaining popularity over the years.3 Although in-office bleaching techniques are associated with higher HP concentrations, a new protocol was described in 2006 consisting of two sixty-minute sessions (six ten-minute applications each session), with a week interval, of a paint-on whitening varnish with a lower HP percentage (6% HP).6 Nowadays, using lower HP techniques has even more relevance since the European Council Directive 2011/84/EU decreed tooth bleaching products as cosmetics and prohibited the use of concentrations higher than 6% HP.7

In-office bleaching effectiveness depends on appropriate field isolation since peroxide-releasing agents can be inactivated when in contact with saliva due to cellular enzymes and diffusion in water environments.8,9 Additionally, the use of a physical barrier is essential for soft-tissue protection since contact with the agents can lead to organic tissue damage.10

In the previously described 6% HP paint-on varnish technique, a Vaseline barrier is indicated as a soft-tissue protection material due to its known occlusion effect and use in dentistry as a gingival barrier.3,6,8,11-13Despite Vaseline’s isolating properties, its semi-solid consistency increases solubility in the presence of fluids, which hinders isolation in the oral environment.

An alternative soft-tissue protection material is the light-curing resin, which grants insolubility in water and superior adhesion to various surfaces, including the gingival tissue; however, it entails a higher economic cost.14‑18

Although the properties of different soft-tissue protection materials are well known, their influence on the bleaching effectiveness is yet to be assessed. Therefore, this clinical study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a 6% HP paint-on whitening varnish used with two different types of soft-tissue protection materials. The following null hypothesis was established: there are no differences in the bleaching effectiveness of an in-office 6% HP paint-on varnish technique when used with two different soft-tissue protection materials.

Material and methods

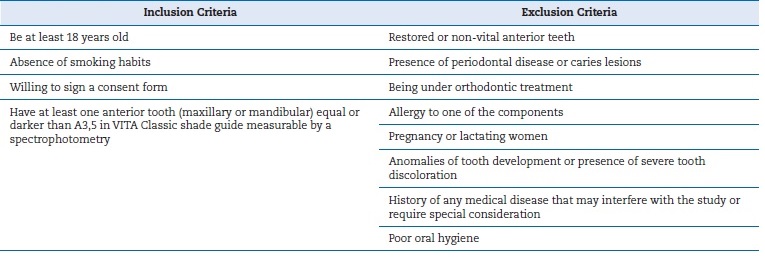

A randomized clinical trial was performed at the Faculty of Dentistry of Universidade de Lisboa after the local ethics committee’s approval. This trial is part of an undergoing tooth-bleaching research registered at the U.S. National Library of Medicine ClinicalTrials.gov website under the reference number NCT03588871, in full compliance with the Helsinki World Medical Association Declaration’s most recente amendments. Patients were recruited consecutively, screened according to inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1), signed an informed consent form, and received professional dental prophylaxis. Then, they were randomly allocated to one of two study groups (GraphPad QuickCals, http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1.cfm), according to diferente soft-tissue protection materials, for an in-office technique protocol with a paint-on varnish at 6% HP concentration (VivaStyle Paint On PIus, lvoclarVivadent®, Liechtenstein): Group 1 - Vaseline (Purified Vaseline, Continente, SonaeMC, Maia, Portugal); Group 2 - block-out resin (OpaldamTM, Ultradent Products, Inc, USA).

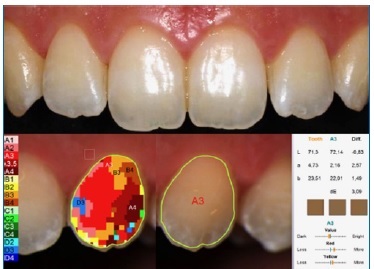

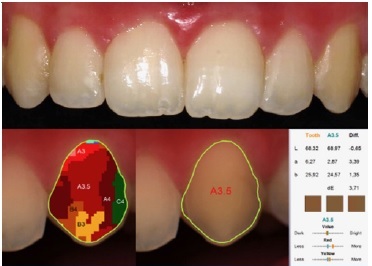

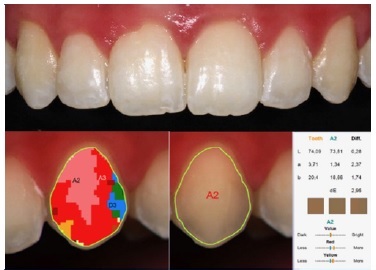

Two previously calibrated experienced dentists conducted in-office tooth bleaching using the 6% HP paint-on varnish technique, following the described clinical protocol: an Optragate retractor was placed in the patient’s mouth (Optragate, lvoclarVivadent®, Liechtenstein); soft-tissue protection materials (Vaseline or block-out resin) were applied to the gingival margin to prevent contact with the peroxide varnish; one thin and uniform layer of the paint-on varnish was applied to the buccal surface of maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (first pre-molar to first pre-molar); after 10 minutes, the varnish was easily removed using an ultrasonic scaling device; and paint-on layers were applied five additional times (10 minutes each), resulting in a total whitening procedure time of approximately 60 minutes per session.6 The clinical protocol was performed in two appointments with a one-week interval and is illustrated in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 for Group 1 and Figures 7, 8, 9, 10,11,12,13, 14 for Group 2. Additionally, the presence or absence of soft-tissue lesions was recorded.

Figure 1 Clinical protocol for Paint‑On Plus Viva Style with Vaseline: 1) An Optragate retractor was placed in the patient’s mouth (Optragate, lvoclarVivadent®, Liechtenstein).

Figure 3 The final appearance of Vaseline in the gingival margin to prevent contact with the varnish.

Figure 4 Application of one thin and uniform layer of the paint‑on varnish to the buccal surface of maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (canine to canine).

Figure 6 After 10 minutes, the varnish was easily removed using an ultrasonic scaling device, and steps presented in Figures 4, 5, and 6 were repeated five additional times (10 minutes each), giving a total whitening procedure time of 60 minutes.

Figure 7 Clinical protocol for Paint‑On Plus VivaStyle with Opal dam® (OpaldamTM, Ultradent Products, Inc, USA): 1) An Optragate retractor was placed in the patient’s mouth, and Opal Dam was applied with the appropriate syringe to the gingival margin to prevent contact with the peroxide varnish.

Figure 11 Application of one thin and uniform layer of the paint‑on varnish to the buccal surface of maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (canine to canine).

Figure 14 After 10 minutes, the varnish was easily removed using an ultrasonic scaling device, and the step presented in Figure 11 was repeated five additional times (10 minutes each), giving a total whitening procedure time of 60 minutes. In the end, Opal Dam was totally removed.

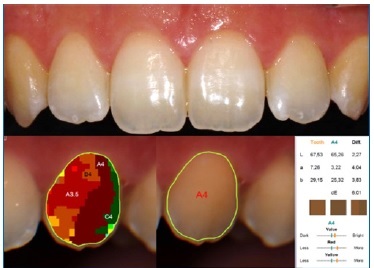

Tooth color was evaluated by spectrophotometry with a proper device: SpectroShade micro (SS) (MHT Optic Research, Niederhasli, Switzerland; serial number HDL3973).19-21The device was operated according to the manufacturer’s instructions by an independent investigator, who performed three measuring rounds in upper and lower anterior teeth (canine to canine - 12 teeth). Results were registered before and after the tooth bleaching treatment in the CIE L*a*b* tooth color coordinates system (CIE L*a*b* values of the buccal tooth surface), and the difference (ΔE00) was calculated to determine bleaching effectiveness. Tooth whiteness was evaluated with a whiteness índex (WID) specifically established for dentistry and based on the CIELAB color notation system. The whiteness index was assessed before (WID1) and after (WID2) the bleaching treatment, and then its difference was calculated (ΔWID).22

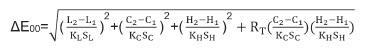

The CIEDE2000 formula, from the Commission Internationale De l’Eclairage (International Commission on Illumination) (CIE), was used to calculate ΔE00. Computations with this color difference formula were performed according to the following equation:23

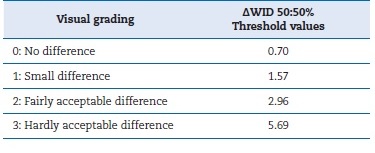

Parametric factors were set to 1. The whiteness index was calculated before and after tooth bleaching with the following formula: WID = 0.511L*-2.324a*-1.100b*.24 Color and whiteness difference perception was assessed according to two major thresholds: perceptibility threshold (PT for ΔE00; WPT for ΔWID) at ΔE00 = 0.8 and ΔWID = 0.72; and acceptability threshold (AT for ΔE00; WAT for ΔWID) at ΔE00 = 1.8 and ΔWID = 2.60. 24- 26ΔWID evaluation followed Perez et al.’s classification system presented in Table 2.26

The sample size was previously determined based on our pilot study’s data, using an online calculator (http://powerandsamplesize.com).18 Considering a mean ΔWID for teeth equal to or darker than A3.5 in VITA Classical (9.9 for Group 1 and 12.9 for Group 2) with a 3.2 standard deviation, we established that 20 patients (10 per group) would be needed for a two-sample comparison test with a superiority limit at a WPT value of 0.72. Calculations were performed with a power of 80% and α of 5%.

All collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Statistics, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). Results were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) of CIE L*a*b* color parameters and WID, with the respective ΔE00 and ΔWID, for all 12 anterior teeth and teeth darker than A3.5. Sample normality was evaluated with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, resulting in a normal distribution. Statistical analysis was performed by parametric tests with a paired t-test conducted to analyze intragroup differences in CIE L*a*b* and WID values and an independente t-test conducted to determine intergroup diferences in ΔE00 and ΔWID. A statistical significance level of α=0.05 was considered.

Results

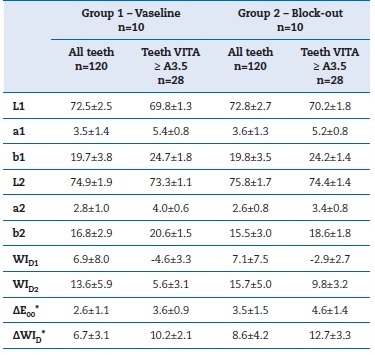

A total of 20 patients were selected and randomly assigned to each group (three males and seven females per group), with a mean and SD of 23.3±2.3 and 21.6±3.0 years of age for Groups 1 and 2, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in color coordinates and WID1 mean values before the bleaching treatment (results depicted in Table 3).

Table 3 Descriptive statistics, before and after tooth bleaching, by study group. Mean values and standard deviation of color coordinates L*a*b*, WID, ΔE00, and ΔWID are presented for each group regarding all teeth and only teeth classified as equal or darker than A3.5 by VITA Classical. [1 - Before treatment; 2 - After treatment; * - Intergroup statistically significant differences for independent t‑test (P<0.01) with α=0.05.]

All treatments occurred without drop-outs, and both groups presented statistically significant differences (P<0.01) for tooth color coordinates after bleaching procedures, with an increase in L* mean value and a decrease in a* and b* mean values. Additionally, the whiteness index results were statistically significant (P<0.01), presenting higher mean values after treatment in both groups. Bleaching effectiveness was verified with the ΔE00 surpassing the AT in 81.7% of cases (90 teeth in Group 1; 106 teeth in Group 2) while the ΔWID was higher than the WAT in 93.3% of cases (110 teeth in Group 1; 114 teeth in Group 2). The ΔWID classification was rated as “hardly acceptable differences” in most cases: 89.2% in Group 1 and 94.2% in Group 2.

When assessing intergroup differences, statistically significant differences were detected in both ΔE00 and ΔWID (P<0.01). Group 2 presented a ΔE00 global mean of 3.5±1.5, equating to approximately 0.9 units above Group 1. The whiteness índex presented similar results, with the ΔWID being significantly higher in Group 2 with a global mean of 8.6±4.2 compared to the 6.7±3.1 values in Group 1. When analyzing teeth darker than A3.5, these differences were more pronounced, with Group 2 presenting 1 unit of ΔE00 and 2.5 units of ΔWID above Group 1 (Table 3).

Five patients from Group 1 and three from Group 2 presented symptomatic small white lesions in the mandibular gingival papilla (symptoms disappeared shortly after the appointment). Figures 15, 16, 17, 18 depict illustrative clinical cases of each group with before and after treatment photos.

Discussion

This clinical study aimed to compare the influence of two diferente types of soft-tissue protection materials on the effectiveness of an in-office 6% HP paint-on whitening varnish.

This technique presented bleaching effectiveness, with overall mean ΔE00 and ΔWID of 3.0±1.4 and 7.7±3.8, respectively, which are above the respective AT and WAT values of 1.8 and 2.6. However, different results were detected between the evaluated soft-tissue protection materials, with the block-out resin presenting superior effectiveness compared to Vaseline, thus rejecting the established null hypothesis.

Regardless of the soft-tissue protection material, this in-office bleaching technique presented whiter and lighter-colored teeth compared to the initial clinical situation. This result was represented by an overall L* increase (resulting in a lighter color) and a*/b* decrease (resulting in a whiter color), based on the CIE L*a*b* system color values’ spectrophotometric analysis, thus reducing operator bias. This study’s findings are in agreement with previous studies that evaluated the effectiveness of this in-office technique.6,14Benbachir et al. evaluated tooth color by spectrophotometry but with a ΔE outdated formula.14,25 To our knowledge, this was the first study to assess efficacy with the CIEDE2000 formula and a new whiteness index based on the CIE L*a*b* system. As observed in previous studies, the detected white non-erosive lesions in soft tissues disappeared shortly after the clinical protocol, with low symptomology.6,14 These mild and transient adverse effects may be related to the lower HP concentration.6,16,27

Considering hydrogen peroxide’s kinetics and petroleum jelly’s transparent semi-solid characteristics, the Vaseline protection technique’s inferior effectiveness may be explained by its isolation incapacity when HP is released into the crevicular fluid.10,11,28 Additionally, due to petroleum jelly’s transparency, Vaseline can be overlooked in the tooth’s vestibular surface, resulting in enamel areas where the bleaching varnish would have less effectiveness. On the other hand, the characteristics of the described block-out resin, which is made of light-curing methacrylate resin and adheres to the gingiva and tooth margins, may allow better isolation capacity from the oral fluids with an easily distinguishable color.17 This reasoning may explain the results suggesting that the clinical protocol for the paint-on varnish Paint On Plus in-office technique could be optimized by modifying the soft-tissue protection material from Vaseline to a block-out resin, increasing bleaching effectiveness. Although block-out resins have been applied in several bleaching studies, to the authors’ knowledge, the effect of the protection technique itself has never been evaluated.3,14,15,29,30The rationale for using Vaseline based on its lower treatment cost may not be justifiable if better detectable results (ΔE00 of 0.9, which suggests a tooth color difference detected by more than 50% individuals) are achievable using light-curing methacrylate resins.

This study was performed in a university setting, involving mostly younger patients with overall good oral hygiene and higher treatment compliance. However, in an older population with darker colored teeth, the bleaching effects could probably be even more noticeable since our results suggest an increase in color difference perception for teeth darker than VITA Classical A3.5.

The influence of different materials or techniques for proper soft-tissue isolation on the effectiveness of in-office bleaching techniques still lacks evidence in the literature. While more clinical studies are always recommended, this study’s results suggest that different soft-tissue protection materials may influence in-office bleaching effectiveness.