Introduction

Despite recent technological and scientific advances regarding dental procedures, fear related to dental treatment still affects a large part of the population and seems to perpetuate over the years.1 Dental fear is associated with a preconceived notion that dental treatment will be painful, which can impair the child’s ability to deal with the office environment and lead dental treatment to failure.2

The etiology of dental anxiety is complex and multifactorial.3 Studies that assess the influence of demographic factos have shown different results, which can be explained by diferente research designs and data collection methods, in addition to the culture, socioeconomic status, changes in the social environment, and dental care systems in each region. Thus, normative data for each culture is necessary.3

In the dental environment, the perception of danger that leads to fear can be associated with children who have never been to a dentist,4 the performance of anesthesia or other procedure that could cause pain, the discomfort of keeping the mouth open for an extended time, or a long and costly treatment plan.5 Another aspect that can contribute to a patient’s anxiety is the patient‑professional relationship because if the child does not feel comfortable or does not trust the dentist, their levels of fear during treatment will probably increase.6

Dentists are in a unique position to assess patient Comfort and educate them about dental anxiety and its coping mechanisms.5 In addition, they have the ability to identify which factos originate or trigger fear and aim to mitigate them through the implementation of appropriate behavior management techniques.7 Children with dental fear should be identified in advance to reduce its consequences,8 since they are more likely to have uncooperative behaviors, causing treatment to be interrupted or postponed and deterioration of oral hygiene.9,10

In order to better understand this condition, some researchers have used the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule‑Dental Subscale (CFSS‑DS), developed by Cuthbert and Melamed in 1982,11 as a tool to measure dental fear in children.2,3,7,10,12Besides being used in different countries and having high reliability, the CFSS‑DS questionnaire has a simple, fast, low‑cost application to evaluate dental fear and anxiety.13 Moreover, as previously reported, the safest method for identifying dental fear in children is through a self‑report questionnaire14 since parents tend to exacerbate their children’s dental fear almost twice.15 Therefore, this study aimed to assess the relationship between the CFSS‑DS questionnaire’s items and the sex and age of children with moderate and high dental fear levels.

Material and methods

This research followed the recommendations of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative for the communication of observational studies (available at: https://www.strobe‑statement.org/index.php?id=available‑checklists). It is a cross‑sectional study carried out in the municipality of Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil.

This municipality has a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.72, a Gini coefficient of 0.58, and about 407,500 inhabitants.16 The present study’s sample was selected from a previous study17 that had a probabilistic sample of 466 schoolchildren, regularly enrolled in elementary schools in the municipality, who had all first permanent molars fully erupted in the oral cavity and had no mental retardation, developmental disorders, neuropsychiatric disorders, and no fixed orthodontic appliance.

Our sample was comprised of 185 children aged 8‑10years of both sexes, who had a minimum score of 32 on the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule‑Dental Subscale questionnaire (CFSS‑DS). Data were collected between March and May 2019 in a school environment. First, the research was presented to the children, who received informed consent forms to hand over to their parents or guardians. On the second visit, with the parents’ authorization, children were transferred to a reserved room to understand the research and assent. Finally, the CFSS‑DS questionnaire was applied in the presence of three researchers to guide the self‑completion by the schoolchildren.

Children had the opportunity to ask questions about the questionnaire and, when necessary, obtain support by reading the questions. Researchers did not influence the children’s responses to the questions. The CFSS‑DS questionnaire was validated for Brazil,18 consisting of 15 items related to various aspects of dental care. Children with a score equal to or greater than 32 were classified as having dental fear.19 As for severity, scores between ≥32 and ≤38 were classified as moderate dental fear, while scores >38 were classified as high fear.18

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS software, version 22.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistical analysis corresponded to calculating absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and measuring central tendency and variability for quantitative variables. The Kolmogorov‑Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of quantitative variables. As data distribution was non‑parametric, the Mann‑Whitney and Kruskal‑Wallis U tests were adopted. The significance level adopted was 5%.

This study was approved by the local Human Research Ethics Committee, under number 3.155.847. Informed consent was obtained from all guardians and individuals included in the study.

Results

The sample’s mean age was 8.95 ± 0.8 years. Most participants were female (59.5%) aged 9 years (37.3%), followed by 8‑year‑olds (34.1%) and 10‑year‑olds (28.6%).

The average total CFSS‑DS score was 40.44 ± 6.81, with a median of 40.00, IIQ25‑75 35-45, a minimum score of 32, and a maximum score of 75. According to the CFSS‑DS, most children had high dental fear (53.5%), and 46.5% had moderate dental fear.

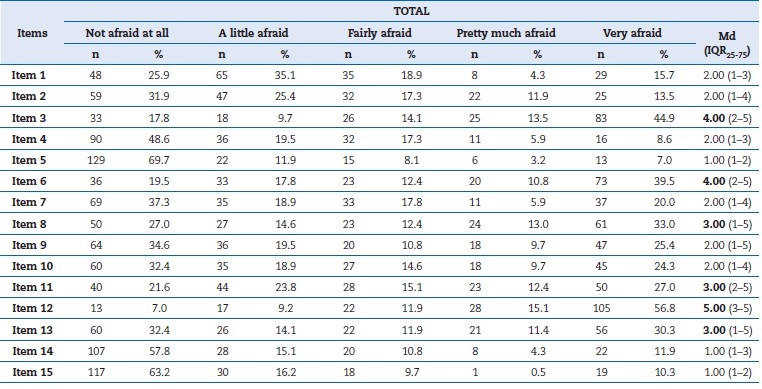

Table 1 shows the distribution, medians, and interquartile range of responses to the CFSS‑DS items by children with high dental fear levels. The following CFSS‑DS items obtained the highest median values: “Injections,” “Having a stranger touch you,” “The dentist drilling,” “Having somebody put instruments in your mouth,” “Choking,” and “Having to go to the hospital” (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution, medians, and interquartile range of responses to the CFSS‑DS items by children with moderate and high dental fear levels.

Md - Median; IQR - Interquartile Range.

Item 1 - “Dentists”; Item 2 - “Doctors”; Item 3 - “Injections”; Item 4 - “Having someone examine your mouth”; Item 5 - “Having to open your mouth”; Item 6 - “Having a stranger touch you”; Item 7 - “Having somebody look at you”; Item 8 - “The dentist drilling”; Item 9 - “The sight of the dentist drilling”; Item 10 - “The noise of the dentist drilling”; Item 11 - “Having somebody put instruments in your mouth”; Item 12 - “Choking”; Item 13 - “Having to go to the hospital”; Item 14 - “People in White uniforms”; Item 15 - “Having the nurse clean your teeth”.

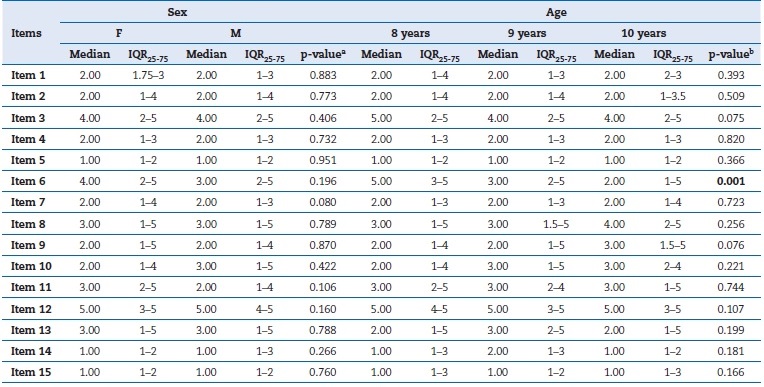

According to Table 2, no significant differences were observed between girls and boys. On the other hand, a significant difference was found between ages for the item “Having a stranger touch you” (p=0.001), with those aged 8 years presenting the highest median (5.00) and those aged 10 years the lowest median (2.00) (Table 2).

Table 2 Medians of scores for each CFSS‑DS item and interquartile range for girls and boys and children aged 8‑10 years with moderate and high dental fear levels.

IQR - Interquartile Range; F - Female; M - Male; a Mann‑Whitney U Test; b Kruskal‑Wallis Test; *p<0,05.

Item 1 - “Dentists”; Item 2 - “Doctors”; Item 3 - “Injections”; Item 4 - “Having someone examine your mouth”; Item 5 - “Having to open your mouth”; Item 6 - “Having a stranger touch you”; Item 7 - “Having somebody look at you”; Item 8 - “The dentist drilling”; Item 9 - “The sight of the dentist drilling”; Item 10 - “The noise of the dentist drilling”; Item 11 - “Having somebody put instruments in your mouth”; Item 12 - “Choking”; Item 13 - “Having to go to the hospital”; Item 14 - “People in White uniforms”; Item 15 - “Having the nurse clean your teeth”.

Discussion

Several factors can influence dental fear, including sex,10 age,3,4,11,15and sociodemographic, economic, and psychosocial characteristics.20 Therefore, being aware of this condition can contribute to the establishment of a trusting relationship between professional and patient and encourage routine care, ensuring that patients maintain ideal oral health.5

The sample of this study was composed of children aged 8‑10 years. Older children have a better understanding of the procedures used than younger children, causing less dental fear.12

With regard to the CFSS‑DS score, an average of 40.44 ± 6.81 and a median of 40.00 were obtained. Similar studies found na average of 37.0 ± 8.89 in English children aged 6‑12 years,2 26.09 ± 10.70 in Saudi children aged 6‑12 years,21 and 24.8 ± 10.3 in Chinese children aged 5-12 years.3 These different averages can be related to methodological differences between surveys and cultural differences between locations, which can lead to discrepant results.22

In the present study, most children had high dental fear, and the following CFSS‑DS items obtained the highest median values: “Injections,” “Having a stranger touch you,” “The dentist drilling,” “Having somebody put instruments in your mouth,” “Choking,” and “Having to go to the dentist.” The item “Injections” was also prevalent in similar studies,2,3,7,10,12 as well as “Choking” and “The dentist drilling.”2,3,10,12Since the main factors for dental fear may be due to invasive dental procedures,9 these findings suggest that the anxiety about certain items proposed by the CFSS‑DS is constant across cultures and peoples, regardless of fear level.

In this research, girls were more prevalent, similar to the results by other authors.7 One of the possible explanations is that girls, in general, are more open and honest about their feelings, including anxiety and fear, compared to boys.1 However, despite the greater female presence, there was no statistically significant difference in the questionnaire items between sexes, unlike in a study conducted in Bulgaria,23 in which girls had higher scores in the CFSS‑DS questionnaire than boys.

In addition, in Indian children, girls had higher scores than boys in the items “Dentists,” “Having somebody look at you,” “The dentist drilling,” and “People in White uniforms,”10 and in Saudi children, girls had higher scores than boys in all items of the questionnaire.21 As Arab boys are raised to be brave and not show fear, this research confirms that cultural factors are relevant in the dental fear evaluation.21

A significant difference between ages was found for the item “Having a stranger touch you” (p=0.001), with children aged 8 years having the highest median (5.00) and those aged 10 years having the lowest median (2.00). This difference was not found in the literature, making it impossible to compare these findings. However, these data may indicate that the dentist is seen as a stranger, being a source of fear for children, since the discomfort expected can be associated with the person who will perform the treatment.21

Researches like the present one are relevant due to providing a better understanding of dental fear and factors surrounding it. Being aware that detecting the different causes

of fear early is very important to solve the problem,2 knowing the factors that generate fear in children, and identifying a potential relationship with age and/or sex allows the pediatric dentist to adopt individual procedures in dental care for a more pleasant moment and, if possible, minimizing dental fear.

Fun activities, games, drawings, and painting materials can be offered in the waiting room to reduce anxiety levels in pediatric patients,6 aiming to alleviate fear at the time of dental care.2 In addition, it is important to tighten the bond between the pediatric patient and the dentist through consultations for educational‑preventive procedures. This approach can be beneficial to establishing the professional‑patient relationship, providing safety, confidence in the professional, and Comfort with the dental environment.

This study has some limitations, such as the cross‑sectional design, which does not allow establishing a cause‑effect relationship. Moreover, the sample size can be considered small, as it prevents the generalization of results to all children of the same age group, but rather for the target population.

On the other hand, the use of a validated instrument widely used in literature to assess dental fear and anxiety and the absence of similar studies in the country should be highlighted as strengths.

Conclusions

The item “Having a stranger touch you” of the CFSS‑DS questionnaire showed a statistically significant difference with age, while no differences were found regarding sex. Knowing the factors related to dental fear can help the dentist identify the patients most susceptible to developing this type of fear. Thus, we believe that an appropriate approach with younger children can promote a relationship of trust, improving oral health conditions, and reducing the need for more invasive treatment.