Introduction

The literature shows that institutionalized people have worse levels of oral health, perhaps due to having major disabilities and/or greater dependence. On the other hand, over the last years, the number of institutionalized people has increased, mainly due to the increase in life expectancy. For many, institutions represent their “home,” and it is these institutions’ responsibility to ensure the provision of basic needs and an adequate quality of life to these individuals. Thus, caregivers are vital to meeting this institutional goal, of which oral health maintenance is an integral part and should be kept in mind.

Oral health promotion programs with hands-on intervention have a positive impact on caregivers’ knowledge and, consequently, on dental plaque index reduction in people with disabilities. Studies report a reduction in plaque rates in special needs patients when caregivers are professionally trained and supervise brushing practice.1-3

A project developed in adults with cerebral palsy (CP) concluded that the highest percentage of dental plaque reduction was related to improved brushing techniques performed by caregivers in the initial phase of the project intervention when the motivation and novelty effect were greatest.2 Also, the caregiver’s professional experience may be important for performing daily oral hygiene. It was evidenced that caregivers who provide oral care to dependent persons for more than two years are more effective in providing oral hygiene care.3,4

The caregivers’ motivation and level of information are related to the institution’s size, the average age of the institutionalized individuals, and their degree of dependence.5 The same was verified in a study conducted in institutions in the district of Lisbon, where caregivers in smaller institutions with in-house staff were more motivated.6

People with CP, due to physical disability, spasticity, and other associated problems, are partially or totally dependent on others to perform effective tooth brushing since this requires hand motor skills and muscle coordination.7 Caregivers have greater difficulty when the individual does not open their mouth, bites the toothbrush, or refuses oral hygiene care.8

A systematic review on the effectiveness of health education interventions for long-term caregivers showed that there was little information on this topic, revealing a lack of evidence on the most effective type of intervention. However, teaching with demonstration and practice training has positive effects on caregivers’ knowledge and skills, as well as on the improvement of residents’ dental hygiene.9

Considering the need for knowledge mentioned above, this study aimed to evaluate the factors that influence the frequency of oral hygiene performed by caregivers in institutionalized adults with CP; determine the caregivers’ difficulties in brush ing adults with CP; relate the difficulties and frequency of oral hygiene performed by caregivers with their sociodemographic characteristics.

Material and Methods

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted by applying a questionnaire addressed to caregivers of institutions that give support to adults with CP. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dental Medicine of the University of Lisbon.

The target population was composed of 294 caregivers for people with CP only, belonging to 27 institutions of the Lisbon district with similar organizational structure, all non-profit and none private. All caregivers (n=257) working at the above-mentioned institutions for more than 6 months with people with special needs that agreed to participate in the study were included.

These institutions do not specifically allocate the most difficult individuals to the most experienced caregivers. The questionnaire applied to the caregivers was based on the first author’s community practice throughout her professional career in institutions for people with special needs. This questionnaire was created for this study and pre-tested in an institution in the outskirts of Lisbon for validation, whose feedback resulted in necessary language adjustments. It consisted of a self-completion document composed of: three questions on the caregivers’ sociodemographic status; two questions on the caregivers’ work characterization; six closed-ended questions and four open-ended questions about the caregiver’s oral hygiene performance, the difficulties encountered, training in oral health, and training needs.

The caregivers were informed by the directors of the institutions about the study’s objectives and made aware of the importance of their participation, emphasizing its anonymous and voluntary nature. The caregivers who were willing to collaborate signed the informed consent. Then, the questionnaire was distributed to the caregivers, who, after its completion, placed it inside a closed box in a pre-defined location, assuring anonymity.

The period indicated for the return of the completed questionnaire was four weeks so that all caregivers had enough time to complete it, despite time-off, leaves, and vacations. The data collected was analyzed using SPSS® (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 25. Non-parametric tests, such as the chi-square test, the Mann-Whitney test, and logistic regression, were used to determine the predictors of frequency and difficulties of brushing (forward stepwise regression method) by caregivers and calculate the prevalence ratios and confidence intervals. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient was performed to look for a correlation between two variables when the variables’ information was defined on a nominal or ordinal scale. A 5% significance level was used for all tests.

Results

A total of 294 questionnaires were distributed, varying between two and 24 per institution, and the response rate was 87.4%. The voluntary participants consisted of 257 caregivers, who were mostly female (n=224; 87.2%) and had a mean age of 41.33 (±10.8) years (min.=21, max.=66). The 9th and 12th grades were the most mentioned levels of education (67.8% n=174). The participants had been working with people with disabilities for an average of 12 years (±9.6) (min.=1, max.=38) and were responsible for the dental hygiene of an average of nine people (±6.8).

Statistically significant weak negative correlations were found between the frequency of caregivers’ brushing and caregivers’ age (p=0.013) and the frequency of caregivers’ brushing and the number of years of work (p<0.001), indicating that younger caregivers with fewer years of work with disabled individuals performed teeth brushing more frequently. Statistically significant relationships were also found between brushing frequency and education, as the better the education, the more frequent the brushing (p=0.001), and between brushing frequency and the number of caregivers doing the brushing (p<0.001), with the higher the number of caregivers in the institution, the higher the frequency of tooth brushing, with weak positive correlations.

The main barriers to dental hygiene routines reported by caregivers were lack of cooperation from users for 25.5% and lack of time to perform dental hygiene routines for 18.1%.

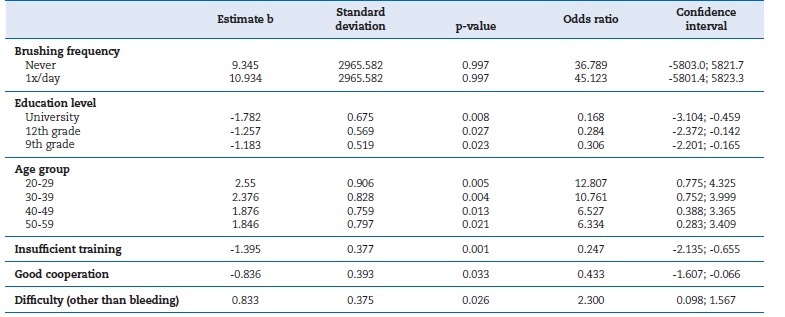

Regarding the reported frequency of brushing performed by caregivers in the institution, 21.8% (n=56) never brushed, slightly more than half (54.5%, n=140) brushed once a day, and 23.7% (n=61) brushed two or more times a day. The probability of brushing less than twice a day was lower in higher educated caregivers (9th grade=-1.183, p=0.023; 12th grade=-1.257, p=0.027; university=-1.782, p=0.008) and younger caregivers.

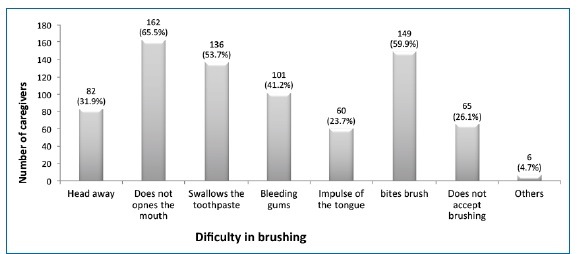

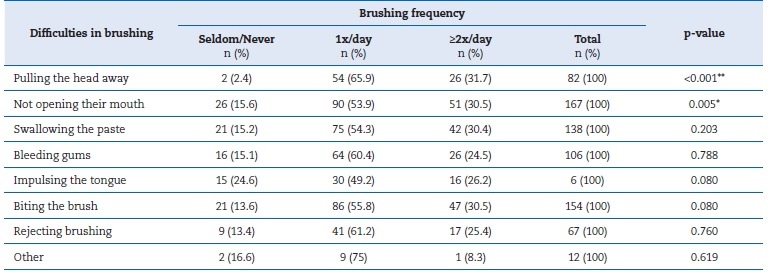

The odds ratio of the lower-order classes (brushing less than twice a day), relative to the reference class (brushing twice a day), increased when individuals felt they had insufficient training (e-(-1.395) =0.247); i.e., the caregivers who felt they had less training in dental hygiene performed brushing more frequently (OR=0.247; p=0.001). The noncooperation of people with CP (e-(-0.836) =0.433; OR=0.433; p=0.033) and the difficulty due to “bleeding” (e-(-0.833) =2.300; OR=2.300; p=0.026) translated into a lower likelihood of brushing teeth two or more times a day (Table 1). Caregivers reported that the biggest obstacles in brushing were difficulty opening the mouth (65%; n=162), gnawing on the toothbrush (59.9%; n=149), and swallowing the toothpaste (53.7%; n=136) (Figure 1).

Table 1 Predictors for brushing frequency by education, age group, training, cooperation, and difficulty.

Adjusted ordinal logistic regression model, with Probit function (variables: education, age, training, motivation, and difficulty)

The forward stepwise regression method retained the variable “has training in oral health,” which explained 54% (Nagelkerke R2=0.054) of the caregivers’ brushing difficulties (OR=3.360; p=0.050), with caregivers with more training having greater brushing difficulties. The most frequently reported difficulties were difficulty opening the mouth (n=167), gnawing the toothbrush (n=154), swallowing the paste (n=138), and pulling the head away (n=82). These difficulties conditioned the frequency of brushing, and most of them only brushed once a day. Among the different variables studied, only pulling the head away (p<0.001) and not opening the mouth (p=0.005) showed statistical significance (Table 2) for brushing difficulty.

Discussion

In the present study, only 12.5% of the respondents were male. The sample imbalance was justified for being a job usually performed by women, an indicator similar to that found in other national studies.10-13 However, quite different from the data obtained in the United States of America (USA), where 73% of the caregivers were male.4

The caregivers’ working time in institutions with people with special needs averaged 12 years, with 30% working for more than 16 years. These data are similar to those obtained in national studies11-13 but different from those of a USA study (mean=3.3 years).4 According to the latter study,4 caregivers who had worked for more than 2 years felt more comfortable performing dental hygiene than those who had worked for less time.

A greater experience by the caregivers also provides greater confidence and comfort for people with special needs, indicating that, ideally, there should not be a high turnover of caregivers. Time and continuity with the same staff are necessary for building a better relationship and making caregivers aware of the special needs of people with dependence.14 In the present study, it was possible to see that the longer the caregiver worked in the institution, the less they toothbrushed; in fact, we found that younger caregivers with fewer years of work with disabled individuals performed teeth brushing more frequently.

The caregivers were responsible for an average of nine people, to whom they provided dental hygiene care. The average number defined by the Portuguese legislation is one direct action helper for eight residents during the daytime.15 In the national studies consulted, the values were similar or higher than those obtained in this study,11-13while they were always lower in international studies.4,12,16,17

Caregivers are essential for the oral health of people with CP, especially those dependent on the care by others to maintain adequate levels of dental hygiene. Most caregivers (58.3%) reported brushing the teeth of the people in their charge at least once a day. Some studies in institutions for people with special needs indicate similar values,18,19but others have found higher percentages.20,21

The main obstacle indicated in this study for not performing toothbrushing was the lack of cooperation from people with CP. This result is in line with those of other studies, which pointed out that when residents offer greater resistance to dental hygiene care, they tend not to receive regular care from caregivers.20,22

Caregivers also mentioned a lack of time to brush (18.1%), which may be related to the high number of dependent people in these institutions. In fact, several studies indicate the lack of time as a factor for not performing dental hygiene.8,23,24 However, only two to three minutes are needed for brushing.25 Thus, if each caregiver is in charge of ten individuals, only 30 minutes are needed in each shift.

This study found that caregivers who had worked for less than 15 years performed brushing more frequently than caregivers who had worked for more years. This finding may be due to the advanced age of the latter and the saturation of this job since we found that higher educated and younger caregivers provide better toothbrush frequency. However, one study reported the opposite: caregivers who had worked for more years were more effective in providing care to people with dependence.4

Some studies point out that brushing can be an invasive procedure, making it difficult. Furthermore, it is natural that institutional or family caregivers are afraid of being bitten. 17,22,27This activity is considered painful, unpleasant, and mentally pointed out as the most irritating task to perform to dependent persons.18 Working in the oral cavity of others presents a psychological difficulty, and one feels reluctance in this intervention, despite the need to deal with other hygienic care of dependent people.23 However, this study did not find this situation, possibly because the caregivers had worked for some time with the same disabled individuals, having a closer and more comfortable relationship with them.

For most caregivers, the major difficulties highlighted were “difficulty opening the mouth,” “gnawing the toothbrush,” “swallowing the toothpaste,” and “pulling the head away”. Several studies report similar difficulties.2,8,9,26Also, the presence of bleeding during tooth brushing contributes to brushing interruption since caregivers are sometimes frightened and afraid of hurting.25

Educational interventions can improve the caregivers’ ability to monitor and perform dental hygiene practices on residents, 15 having a positive impact on clinical outcomes.2,24,28However, these improvements are short-term.23,29In the present study, the caregivers who had more training were the ones who reported feeling more difficulty in performing brushing, which may result from being more aware of the importance of a correct technique and being unable to perform dental hygiene correctly.

The present study had some limitations, such as the disparate number of caregivers surveyed in each institution and having a convenience sample since it is limited only to the district of Lisbon. Also, some institutions are not only for people with CP, and the characteristics of other disabilities may have influenced the caregivers. Another limitation found in some institutions was the time delay for collecting the questionnaires since, due to the shift schedules of most caregivers, some institutions took a long time to collect all the questionnaires.

Another limitation of this study is the difficulty of finding European articles on some parameters of this theme. This difficulty reinforces the relevance of this study because it fills a gap in the European scientific literature.

Conclusions

The frequency of dental hygiene in institutions for adults with CP may be influenced by the sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers since a younger age and a higher level of education of the caregiver increased the frequency of oral care to the people with CP. The caregivers reported that brushing was more difficult when the individuals with CP did not cooperate, namely, when they made it difficult to insert the toothbrush in the mouth, swallowed the toothpaste, and pulled the head away.