Introduction

Knowledge of the internal anatomy and possible variations in the morphology of the root canal system is essential for performing successful endodontic therapy.1 Clinicians must be prepared to identify and perform endodontic treatment of teeth that exhibit unusual configurations to ensure that the entire root canal system will be debrided and filled. Missed and untreated root canals can lead to unsuccessful endodontic treatment and may result in the development of apical periodontitis in up to 98.0% of cases.2

The permanent mandibular canines are among the dental groups that may have variations. Usually, the mandibular canine has one root with one root canal; however, frequent variations of two root canals and possibly even three root canals may occur. An uncommon root configuration also found is a mandibular canine with two roots and two canals.3 Three in-vivo studies using cone-beam computed tomography reported a prevalence of mandibular canines with two roots of 3.1%, 3.0%, and 2.41%, respectively.4-6 Another study found differences between genders, with a prevalence of 1.5% and 3.8% for males and females, respectively.7 Ex-vivo studies reported a prevalence of 1.7% and 11.1%, respectively.8,9

In view of the previous considerations, clinicians should be able to diagnose and perform endodontic treatment in a safe and predictable manner. Therefore, this report aims to

present the diagnosis and endodontic retreatment of two clinical cases of permanent mandibular canines with two roots.

Case Reports

After clinical and radiographic evaluation, a diagnosis was established, the condition was explained to the patients, and the treatment options were proposed. The patients signed a term of free and informed consent before treatment was initiated.

All the teeth were anesthetized with a mental nerve block infiltration using 1.8 ml of 2.0% mepivacaine with 1:100000 epinephrine (DFL, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and rubber dam isolation was established. The working length was determined with an electronic apex locator (Root Zx II, Morita, USA) and confirmed radiographically. All instrumentation was performed under copious syringe irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite. In all cases, the final rinse procedure also included irrigation for three minutes with 17.0% EDTA prior to a final sodium hypochlorite rinse before drying the canal with matched paper points # 30 (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany).

The whole treatment required two appointments. An intracanal dressing with calcium hydroxide paste (UltraCal XS, Ultradent, USA) was applied between visits, and a glass-ionomer cement (Ionofast, Biodinâmica, Brazil) was used as a provisional restoration.

In the second visit, a final irrigation protocol that included rinses with 17.0% EDTA and 2.5% sodium hypochlorite was performed. The canals were dried with paper points, and root canal filling was performed with gutta-percha cones (Odous de Deus, Belo Horizonte, Brazil), using the single-cone technique and AH Plus sealer (Dentsply, Konstanz, Germany) in the first case report and BioRootTM RCS (Septodont, Saint-Maurdes-Fossés, France) in the second. The access cavities were temporarily restored, and the patients were referred for coronal rehabilitation.

Case #1

The patient, a 63-year-old Caucasian woman, was referred due to odontalgia in tooth 43 diagnosed as symptomatic apical periodontitis. The endodontic treatment had been performed 2 months earlier, and because the tooth remained sensitive, the prosthetist did not proceed with the prosthetic treatment.

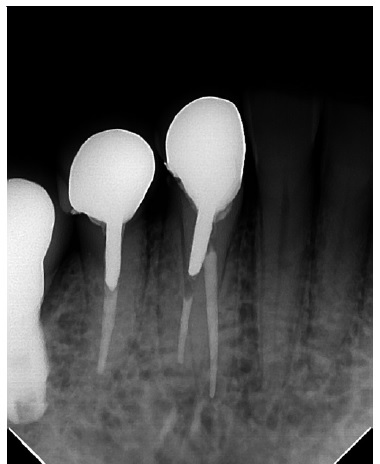

As the pain intensified, the patient was referred for an evaluation. The initial periapical radiograph suggested the presence of an additional root. A second radiograph, taken in the mesiodistal direction, confirmed the presence of that second lingual root, which had not been treated (Figures 1 and 2).

After suitable anesthesia, the absolute isolation clamp required on the tooth to be treated was positioned to place it on tooth 44, and teeth 43 and 42 were isolated (Figure 3). A round high-speed diamond bur (1014, KG Sorensen, Cotia, Brazil) was used to remove the temporary filling where an isthmus in the lingual region had previously been observed. After locating the lingual canal with a C-Pilot #10 file (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany) (Figure 3), the purulent exudate was drained. The canal was negotiated with C-Pilot # 10 and # 15 files (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany) and instrumented with a Mtwo rotary system (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany), up to instrument #35.04, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The root canal was disinfected, and a calcium hydroxide dressing was used for two weeks.

At the second visit, because the tooth was asymptomatic, the clinician decided not to retreat the buccal canal. A new disinfection protocol was performed, and root canal obturation was completed (Figure 4). The patient was referred for prosthetic rehabilitation. After 18 months, a follow-up X-ray suggested normality of the periapical tissues, and the patient showed no symptoms (Figure 5).

Case #2

The patient, a 77-year-old Caucasian woman, was referred for endodontic retreatment of tooth 33 due to asymptomatic apical periodontitis (Figure 6). The access cavity was performed with a round high-speed diamond bur (1014, KG Sorensen, Cotia, Brazil) under suitable anesthesia and rubber dam isolation.

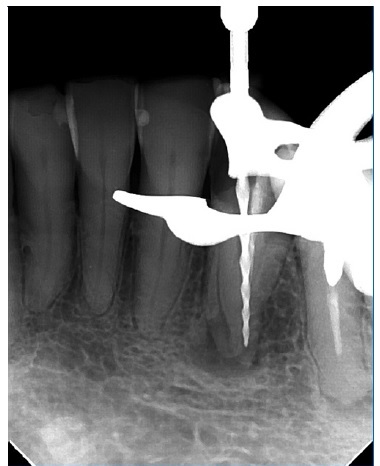

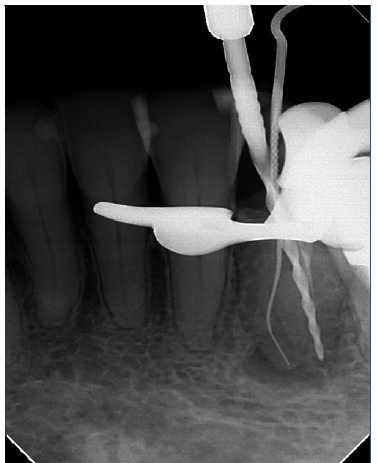

After locating the root canal, the filling material was removed using a Reciproc Classic #25 instrument (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany), without solvent, and a radiograph was taken to confirm the working length (Figure 7). The radiograph taken from a mesioradial angle suggested the presence of an additional root on the lingual surface. An operating microscope (16x magnification) and a pear-shaped diamond ultrasonic tip (E6D, Helse, São Paulo, Brazil) were used to remove dentin in the lingual direction, revealing the presence of an isthmus and evidencing the lingual root canal. The root canal was located and negotiated with C-Pilot # 10 and # 15 files (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany) (Figure 8) and instrumented with a Reciproc

Figure 7 Radiograph after filling was removed from the buccal canal, showing evidence of the lingual root.

Figure 8 Lingual canal negotiated with a #15 hand file and buccal canal instrumented with a Reciproc Blue #40.

Blue #25 (VDW Dental, Munich, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The buccal root canal was instrumented with a Reciproc Blue #40 instrument. The root canals were disinfected, and a calcium hydroxide dressing was used between visits.

One month later, in the second visit, a new disinfection protocol was performed, and root canal obturation was completed (Figure 9). The patient was returned to her referring clinician to continue her dental treatment. A follow-up X-ray was taken 5 months later. Radiographic findings indicated a healing process of the periapical lesion (Figure 10).

Discussion and Conclusions

The anatomy of root canal systems and the anatomical variations found in the different types of teeth provide information that might improve the outcome of endodontic treatment.10 In both cases reported, the unsuccessful treatment in the primary endodontic intervention was related to the presence of microorganisms in the root canals that were not identified, which can result from an unsystematic radiographic examination, inadequate access cavities, or improper observation of the pulp chamber.11

As radiographs only provide two-dimensional information, they may not reveal missed canals in all cases. However, this may be overcome by cone-beam computed tomography, which provides three-dimensional information and higher sensitivity for evaluating changes in hard tissues.2 In the present two cases, periapical radiographs taken at a mesial angle were used to find canals that had been overlooked.

Different angles are recommended to help find and locate extra canals.11-13 In both cases, the two-rooted mandibular canines had two canals, one in each root, in agreement with several studies.8,9,14-16 They were classified as type V according to Vertucci,12 and coded as 233 1B1 L1 according to Ahmed’s system.17

Mandibular canines with two roots are generally shorter than single-rooted canines.15 The roots are in a bucolingual direction, with the buccal root being slightly longer than the lingual root,6 as reported in several studies.4,15,16 However, one study found no significant difference in the lengths of the buccal and lingual roots in females.6 Regarding wideness, two studies have reported that the buccal root was larger than the lingual root in 47.7% and 41.5% of teeth.14,15

On the other hand, another study found the same prevalence of lingual roots larger than buccal roots (36.0%) and buccal roots larger than lingual roots (36.0%).16 These studies also found 43.1%, 35.1%, and 28.0% of mandibular canines with equal-sized roots.14-16

Root bifurcation has been reported as more prevalente (45.4%, 81.2%, and 58.0%) in the middle third6,14,16and common in the apical third (35.1% and 44.0%).14,16 However, one study found bifurcation in the apical third to be more prevalente (56.9%), followed by the middle third (40%).15 These studies described bifurcation in the coronal third as the rarest. 6,14-16

Studies have reported a prevalence of roots with buccal curvature of 49.2%, 27.2%, and 14.0% in buccal roots and 37.6%, 69.2%, and 79.0% in lingual roots, observed from a bucolingual aspect.14-16 Straight roots were observed in 38.5%, 41.5%, and 58.0% of buccal roots14-16 and 29.2% and 29.8% of lingual roots.14,15 Only a small proportion of the roots exhibited a lingual curvature, with 12.3%, 2.6%, and 7.0% in buccal roots14-16 and 1.5% and 2.6% in lingual roots.14,15

Single-rooted mandibular canines are moderately narrow in the mesiodistal direction but very broad in the bucolingual direction, and comparable anatomy is observed in two-rooted canines.3,15 Furthermore, in two-rooted canines, a lingual shoulder must be removed to gain access to the entrance of a second canal, as the lingual wall has an almost slit-like appearance compared with the larger buccal wall.3 The suggested technique has been to cut an “inverted pear-shaped” cavity with sufficient lingual extension to remove the lingual shoulder of the dentine for adequate instrumentation.15

The pulp chamber floor and wall anatomy also help determine which morphology is actually present.13 The use of magnification and illumination is considered of key importance for the successful treatment outcome of endodontic procedures.11,13,18 In the second case reported, an operating microscope and ultrasonic tips were used for locating the root canals.

The single-cone technique using gutta-percha cones with greater taper turns the root canal filling into a faster and simpler procedure while minimizing the forces applied to the root canal walls by spreaders without decreasing the quality of the apical sealing.19 In the first case, the epoxy resin-based sealer AH Plus (Dentsply, Konstanz, Germany) was used. In the second case, the most recent bioceramic sealer BioRootTM RCS (Septodont, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France) was used, which, among its main properties, presents bioactivity. Both sealers have high success rates with excellent clinical results.20

To achieve a successful endodontic treatment in teeth with anatomical variations, it is important that the clinician is knowledgeable and trained and uses the technological resources available, such as magnification and ultrasonic tips.21