Introduction

Metastasis is a complex biological process that involves cell detachment from the original tissue, invasion, survival, proliferation, and overcoming of the immune system. Carcinoma cells have little adhesiveness to the tissue to which they belong and can easily detach from it. Once released, the tumor cells permeate the lamina basalis and invade the adjacente tissues. The next step for the tumor cell is the formation of new blood vessels, called angiogenesis. After it starts to grow inside the adjacent tissues as a tumor, the cells can gain access to the bloodstream more easily. In this way, the cells can spread to another region, initiating a new cell proliferation.1

Although rare, uterine tumors may cause metastasis in the mouth and maxillofacial region,2,5-7with a prevalence lower than 1% among the malignant tumors of the oral cavity.7 Irani et al.,7 studying 453 cases of metastasis to the jaw bone, only found squamous cell carcinoma in 3.9% of the cases (18 cases). Still, squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor of the oral cavity.8,9 It is characterized by irregular or rounded nucleolus, scattered chromatin in front of the nuclear membrane, and recognizable nucleoli. In the cytoplasm, mitochondria, smooth endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes, and lipidic inclusions are present; however, these structures are underdeveloped and smaller than normal.9 Tanaka et al.,9 comparing the differences between metastatic and non-metastatic squamous cell carcinomas, found a small number of desmosomes in the metastatic group, mainly located in the microvilli. The non-metastatic group presented a few microvilli with a large number of desmosomes. They concluded that the metastatic group had weaker adhesiveness (due to the small number of desmosomes) and higher cell activity. In the 1950s, the primary recommendation for treating squamous cell carcinoma in the maxillomandibular region was the preventive resection for any case with suspected boné involvement. This approach was based on the belief that the lingual periosteum’s lymphatic drainage was involved in the drainage of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Greer described the resection technique in 1953, but the understanding of the oral cavity lymphatic drainage only increased with Marchetta’s work in 1971. In 1981, Carter’s work clarified the bone invasion mechanisms of this tumor, and the conservative treatments started to be used on a large scale, according to the individual characteristics of each lesion, which would indicate the best treatment choice.10

The case described below is that of a patient who underwent treatment for uterus squamous cell carcinoma and some months later developed a tumor in the mandible. It should be highlighted that the authors did not find a parallel case in the literature, meaning that we may be in the presence of the first case report.

Case report

A 49-year-old white female patient was referred to the Oncology Service of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia Hospital in Ponta Grossa (Brazil) in March 2018 after a positive biopsy for a grade-II intraepithelial cervical neoplasia. There, she underwent a biopsy of the uterus cervix, and the lesion was diagnosed as a moderately differentiated invasive non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. The treatment consisted of 28 sessions of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. After beginning tumor treatment, the patient reported painful symptoms in the left mandibular body region. In October 2018, the patient was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Service of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia of Ponta Grossa due to pain on the left side of the mandible. A periapical radiograph showed a radiolucent area in the region (Figure 1), and the tomographic examination revealed a pathologic fracture of the mandible. She was referred to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Traumatology sector of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia of Ponta Grossa, where a tomography of the region showed a large lesion in the left mandibular body (Figure 2). We chose the mandibular segmentary resection, with secondary biopsy, as surgical treatment because the mandibular basal cortical was compromised by the tumor (with a pathological fracture) and the patient had a history of a malignant tumor.

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia and nasotracheal intubation, with the patient in dorsal decubitus. Antibiotic prophylaxis was performed with Kefazol® (i.v. cefazolin 500mg) and Flagyl® (i.v. metronidazole 500 mg). Asepsis was performed on the left side with topical polyvinylpyrrolidone-iodine, followed by the apposition of sterile barriers.

The procedure began with the infiltration of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 in the mandibular angle region. The submandibular access was chosen. About 1 cm below the margin of the mandibular angle, a transcutaneous incision of about 10 cm with a blade 15 was made from the mandibular angle region to the mandibular parasymphyseal region. Afterward, the platysma muscle was released with the help of Metzenbaum scissors and carefully divulsed to locate the facial artery and facial nerve, which lie immediately below this muscle. Once located, the facial artery was ligated, and the nerve was released to the flap plane. Then, the incision of the adipose tissue to the pterygomasseteric sling location was completed. After locating the sling, the subperiosteal incision was performed across the lower mandibular margin.

The periosteum of the entire area was exposed and detached, exposing the entire mandibular body. The lesion was in the mandibular body region, becoming visible at the end of the access. The left mandibular body was resected (Figure 3) with cutters, thus proceeding with tumor excision (Figure 4). The mandibular lesion underwent excisional biopsy, where three tissue samples were removed: one from the soft tissue of the mandible’s lateral surface, the second from mandibular boné tissue, and the third from the submandibular region. The pieces were placed in separate containers with 10% formalin and sent for histopathological examination. A 2.4-mm reconstruction plate system was fixated to restore the mandibular contour, and the skin was sutured with 5-0 nylon. The patient evolved without complications in the mandibular postoperative period.

The mandibular biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with areas of necrosis, infiltrating salivary glands, connective tissue, and striated skeletal muscle. The immunocytochemical examination showed that the sample was compatible with low differentiate carcinoma infiltration. The histology slides could not be recovered. The patient was then referred to the Oncology Service of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia of Ponta Grossa for treatment. However, the patient died in January of 2019 due to complications of the uterine tumor.

Discussion and conclusions

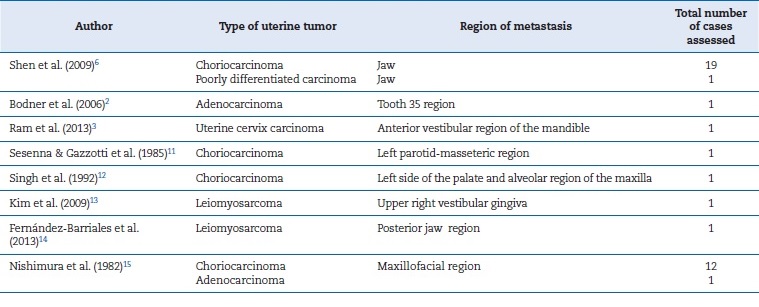

Few reports in the literature cite metastases from uterine tumors to the maxillofacial region. Table 1 shows the findings of uterus metastasis to the maxillofacial region, with an apparent prevalence of choriocarcinoma.2,3,6,11-15A study by Hirshberg et al.1 found tumors originating from the female genital organs (uterus, ovary, cervix, uterine tubes - without specification of each case) in 28 out of 169 patients. Of these, 17 tumors were metastatic in maxillary and mandibular bones and 11 in the oral mucosa.

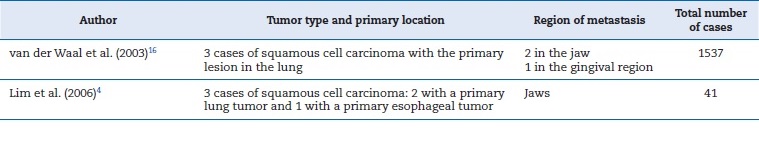

Cases showing squamous cell carcinomas with metastasis in the maxillofacial region with primary lesions in organs other than the uterus have been reported (Table 2).4,16 In our search, we did not find any case of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in the maxillofacial region whose primary lesion was in the uterine region, showing it to be highly rare.

Table 2 Tumors with the primary lesion located elsewhere than the uterus with metastasis in the maxillofacial region.

In the present case, the treatment chosen was resection of the left mandibular body affected by the lesion because a large part of the mandibular body was involved in the lesion, and there was no other option for treatment. Ord et al.10 compared segment resection (23 cases) and marginal resection (30 cases) as treatments for squamous cell carcinoma in the mandible. They found that marginal resection is applicable for mandibular tumors that allow maintaining a basal bone margin of at least 1 cm, being more suitable for tumors in earlier stages. Their results also indicated that the technique is unsuitable for patients with atrophic mandibles due to the difficulty of maintaining bone remnants.

This finding corroborates the present case, whose patient had na atrophic mandible, thus quickly taken by the lesion, with no alternative to resectioning the segment. Other authors, in recente studies, also sought new approaches to mandibulectomy for less aggressive tumors that do not include the resection of segments.17

The oncological treatment of the patient was based on chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the region of the uterine tumor. The patient died a few months after the completion of radiotherapy due to complications related to the tumors, thus discontinuing the treatment. When studying the type of treatment used for squamous cell carcinoma, the literature shows that chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy is a very effective approach. Foster et al.,8 in a 20-year retrospective study, evaluated 140 patients with squamous cell carcinoma that were under definitive chemoradiotherapy based on 5-fluorouracil and hydroxyurea, in addition to taxane, platinum agents, cetuximab, and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, and also intensity-modulated radiotherapy with a dose of 70-75 Gy. The postoperative follow-up was 5.7 years and had a general survival rate of 63.2%, which is higher than usually reported.18

Although the patient died due to complications of the initial uterine tumor, the survival of patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the maxillofacial region has a relative prognosis. In a previously described study, van der Waal et al.16 analyzed three cases of metastatic squamous cell carcinomas to the oral cavity from a primary lesion in the lung. The authors reported that the mean survival time for the three cases studied was 12 months (metastasis to mandible), 2 months (metastasis to mandible and maxilla), and 26 months (metastasis to gingiva). In turn, Hirshberg et al.1 reported that the survival of patients with metastases from tumors in the maxillofacial region was 7 months in most cases.

The mean time between the diagnosis of the initial lesion and the metastasis was 40 months. However, some metástases were reported in a period longer than 10 years after the diagnosis of the initial lesion. Irani,7 who studied 453 cases of metastatic lesions to the maxillomandibular region, observed that the time between diagnosis of the primary lesion and metastasis was from 1 week to 10 years, and the survival rate after diagnosis ranged from 1 week to 5 years, thus demonstrating patients to have an uncertain mean life span.

We conclude that it is important for the dentist and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon to dedicate special attention to the oral and maxillofacial examination in patients with uterine squamous cell carcinoma, thus minimizing the morbidity and mortality of this population.