Introduction

Anxiety is an emotion with negative impacts beyond adverse feelings and changes in daily behaviors. In particular, anxiety hinders the ability to make decisions and respond to some daily tasks.1 It can be experienced at work, when entering the labor market, before exams, among other moments and circumstances. It is an emotional condition that precedes a threatening stimulus, which may not even be identified.2,3

Some symptoms of anxiety are feeling tired, having difficulty concentrating, becoming easily irritated, having muscle tension, having difficulty controlling feelings of worry, and having sleeping problems.4

Undergoing dental treatments is commonly assumed to be potentially anxiety-producing, as exposed in the scientific literature. A study by Lin5 indicated that anxiety associated with dental appointments is related to patients’ negative experiences in previous dental appointments. Accordingly, patients with previous positive experiences had lower anxiety levels than those with previous negative experiences.

Two circumstances determine patient anxiety when exposed to dental treatments: the moment before anesthesia, which often causes a state of phobia, and the dental treatment itself.6 A recent study by Caltabiano7 revealed that women had more anxiety than men, with some factors, such as the injection of local anesthesia and tooth drilling, increasing anxiety levels. In terms of age, younger patients had higher anxiety about dental treatment than older patients. That study also evaluated whether several factors caused patients to feel more or less anxiety during dental treatment. The factors that caused increased anxiety levels were the appointment time and patients knowing they would have future appointments. The factors that caused decreased anxiety levels were a calm, clinical environment and the patient’s active participation in the treatment (e.g., holding the vacuum cleaner).

When providing care for patients’ oral pathologies, dentists should also focus on their psychological and psychological needs. The time the dentist spends with the patient allows for building a relationship of trust that may help complete the treatment and make the patient feel less anxious.8 If the dentist realizes the patient is anxious at the first appointment, they can help manage it from the first moment. Some strategies might include talking calmly with the patient to identify situations that cause fear or anxiety, asking open-ended questions that can help guide the conversation in the right direction, advising deep breathing, and normalizing feelings of anxiety. Since the dental office environment can play an important role in anxiety, a positive, calm environment is suggested, with information always available to make the patient feel comfortable.2

Given this scenario and the need to synthesize the existing evidence on dental treatment-related anxiety, this study aimed to map the scientific literature regarding anxiety about dental treatment in adults, using a scoping review. To answer this objective, we defined the following research questions: a) what factors are drivers of dental-treatment anxiety in adults?; b) what factors are protective factors of dental-treatment anxiety in adults?; c) what are the actual and/or potential consequences of dental-treatment anxiety in adults?

We considered it relevant to map the most extensive possible information on this topic, aggregate it, and make it easier for dentists to consult to provide high-quality practice. Scoping reviews are an excellent approach for this type of objective.9

Methods

A detailed protocol of the present scoping review was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) with the code (10.17605/OSF.IO/5PDYW). The article writing was structured according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

This scoping review included articles published in online databases. We chose to include Portuguese, English, and Spanish studies because these are the languages mastered by the researchers, allowing a good quality of evidence selection and respective data extraction. Moreover, there was no restriction on the publication date since a scoping review aims to review all existing literature on a given topic.10 All articles with full text available were included regardless of geographic location, without specific ethnicity or gender criteria. However, we only included studies concerning adults (persons aged 18 years or older) because anxiety manifests itself differently in children and adolescents.11

This review focused on studies addressing anxiety in patients attending the dental office. We sought to include studies examining dental-treatment anxiety, its consequences, and the factors that protect against and/or enhance it. For the review, anxiety was considered an emotion with negative impacts, including adverse feelings and changes in daily behaviors.1 Other emotions, such as fear or phobias of the dentist or dental treatment, were excluded due to not falling within the definition of anxiety.

We included studies focusing on anxiety in adults attending dental offices in private clinics, hospitals, and private and/or public clinics. Because the central concept of the review is “dental-treatment anxiety carried out by professional dentists,” we excluded studies in which dental students carried out dental treatments.

Research terms were identified using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and defined based on the research questions. On 14 February 2022, the databases CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO host), MEDLINE With full text (via EBSCO host), and Web of Science Core Collection (via Web of Science) were used to search for the following terms: (“dental anxiety” OR “dental anxieties”) AND (“factor*” OR “cause*” OR “reason*” OR “consequence*” OR “effect*” OR “outcome*” OR “repercussion*”). The search process is detailed in Table 1.

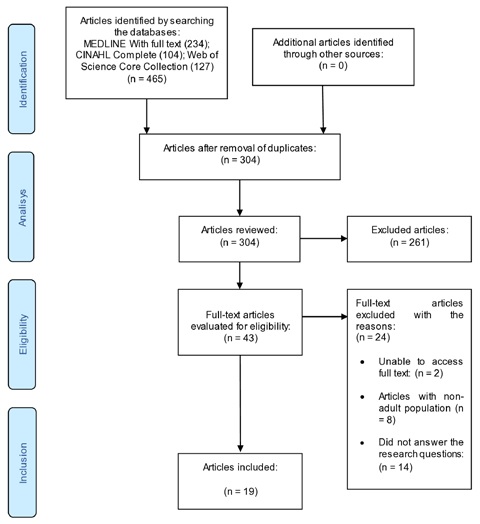

Articles were exported to Endnote Web® software (Clarivate Analytics). A total of 465 articles were identified, and duplicates were removed. The first analysis was done by independently reading the titles and abstracts to select the articles that answered the research questions. Then, two independent researchers (BC and FS) with the same objective read the full text of the selected articles. During this analysis, whenever there was disagreement about the inclusion or exclusion of a particular article, it was sent to a third independent researcher (CG) to resolve the disagreement.

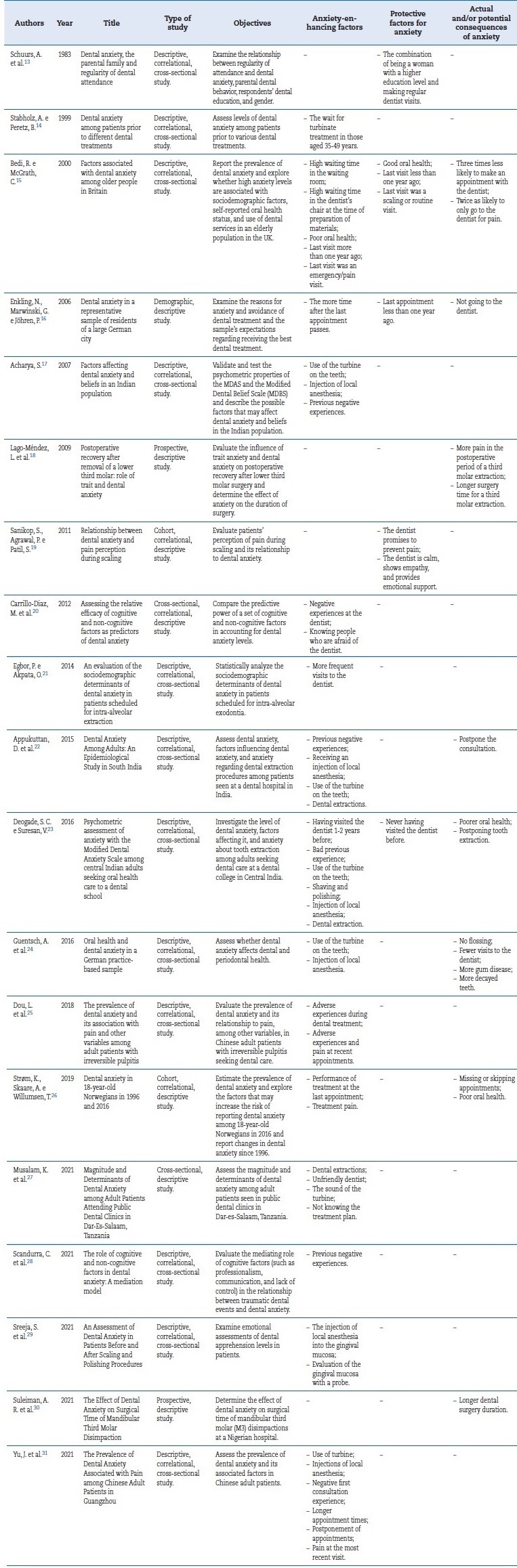

The methodological quality of the articles was not assessed because the objective of a scoping review is to map all the existing literature on the topic.12 Table 2 contains the information of the articles, with the title, author, year of publication, type of study, objectives, and individual results, and was developed based on the model recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute for extracting details, characteristics, and results from the articles.12

Results

A total of 465 articles were identified. The full text of two articles could not be accessed, eight involved a non-adult population, and 14 did not answer the research questions. Finally, 19 articles were included for analysis13-31 after full-text reading and guided analysis of the review questions. The steps of the study selection for inclusion in the scoping review are described in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1).

The results regarding anxiety-enhancing factors, protective factors, and actual and/or potential consequences of anxiety are reported in Table 1. Most studies were descriptive, correlational, and cross-sectional. There was a great diversity in the publication years of the studies, scattered between 1983 and 2021, with the most significant number of studies published in the year 2021, i.e., very recently. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, research in this area was incipient, increased essentially from 2015, and equaled the number of publications of the five previous years in 2020/21. Regarding the countries of publication, one of the articles was published in America, three in Africa, seven in Europe, and eight in Asia. The country with the most publications was India. The total number of participants in the analyzed studies was 6959, ranging from a minimum of 78 to a maximum of 1360.

The main anxiety-enhancing factors were using a turbine on teeth, previous negative experiences, injection with local anesthesia, and pain during treatment. The main anxiety-protective factors were regular visits to the dentist, the last visit being a scaling or routine appointment, and the dentist being calm, empathetic, and emotionally supportive. The main actual and/or potential consequences of anxiety were postponing, missing, or skipping appointments and poor oral health.

Discussion

The use of a turbine on the teeth was one of the factors most often mentioned as anxiety-provoking in dental visits. Namely, Siegel32 reported that patients tended not to visit the dentist for five or more years because using a turbine on their teeth caused them anxiety. The same was indicated by Saincher,33 who found that blood oxygen saturation levels increased when the turbine was used on the teeth, indicating a higher level of anxiety.

The literature also identified local anesthesia injection as an anxiety factor, having been associated with the patients’ fear of needles and injections.34 When asked how they would feel if the turbine were used on their teeth and they were given local anesthesia, patients tended to feel more anxious.35

Moreover, many patients associated pain with local anesthesia injections.32 Pain during treatment was another anxiety factor identified in this review. Alroomy36 found a positive correlation between pain and anxiety, and another study related different anxiety levels to different pain levels in dental treatments, with people with more anxiety feeling more pain.37 Finally, Suhani34 reported that anxiety tended to be high in patients with previous negative experiences.

Regarding factors that protect against anxiety, two studies reported regular dentist visits as among the most frequently

mentioned factors.34,38 In both studies, anxiety and regular visits to the dentist were inversely related: the more visits to the dentist, the lower the level of anxiety. Another critical factor was whether the last visit was a scaling or a routine visit, and patient anxiety levels did not differ significantly between scaling/polishing and routine visits.7 Likewise, Alwan’s study,39 which indicated that blood glucose levels increase when anxiety increases, reported no significant changes in glucose levels after scaling. The last factor was the dental doctor being calm, showing empathy, and providing emotional support. Most participants wanted the opportunity to build a trusting relationship with the dentist and receive support and advice.40 Jevean and Ramseier41 emphasized that one of the techniques used with anxiety was to be calm and use language more adapted to the patient’s profile.

The main actual and/or potential consequences of anxiety were postponing, missing, or rescheduling appointments. Suhani34 and Jevean and Ramseier41 indicated that most participants agreed that anxiety increased the number of absences and postponement of appointments. Another frequent consequence was poor oral health, with Mueller42 pointing out that anxiety is related to oral hygiene and attitudes toward oral health. Khan43 also indicated a significant association between oral health and anxiety.

The limitations of this study were searching only databases, leaving out the analysis of books and theses (gray literature), with potentially additional information. Moreover, the search was conducted only in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, which may have limited the results, so it is essential to look at them carefully. It was not possible to access articles that did not have the full text available for free. Although the selection of articles for this study was made rigorously and followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines, some relevant publications may have been left out, a limitation inherent to any review work. In a future study, we propose broadening the range of languages and research sites to obtain even more extensive scientific evidence.

Conclusions

Factors that increase oral health anxiety are using turbines on teeth, previous negative experiences, injection with local anesthesia, and pain during treatment. Anxiety-protecting factors are frequent visits to the dentist, the last visit being a scaling or routine appointment, and the dentist being calm, empathetic, and emotionally supportive. The actual and/or potential consequences of anxiety are postponing, missing, or canceling appointments and poor oral health.

The present study mapped a substantial part of the scientific literature regarding dental-treatment anxiety in adults.

With its results, we hope to contribute to a more excellent and better knowledge of the impact of dental-treatment anxiety, helping reduce patients’ avoidance of dental visits due to this cause and enhance the well-being of people who need regular oral care. This study may help dentists anticipate anxiety situations in their dental practice, allowing them to adopt preventive strategies based on previous anxiety assessment methodologies. It may also contribute to teaching by enriching the knowledge on this topic and including it in the syllabus of integrated master’s degrees in Dentistry.