Introduction

The word “malocclusion” comes from Latin, meaning “bad bite.” It is used to describe teeth that do not fit together properly.1 Malocclusion is a highly prevalent,2 multifactorial condition associated with developmental, genetic, hereditary, and behavioral factors.3,4 It negatively impacts the individual’s quality of life, being considered a public health problem.5

However, malocclusion is not just a single condition; it encompasses a set of oral conditions that can affect an individual’s oral health. In 1964, Bjöerk et al.6 classified malocclusions into dentition anomalies, occlusion anomalies, and spacing conditions.

Dentition anomalies include those related to teeth (supernumerary teeth, aplasia, and tooth malformations), eruption (ectopic, hindered, arrested transposition, and persistent deciduous teeth), and tooth alignment (rotated teeth, inversion of incisors, and tipping). Occlusal anomalies are further divided into the following: sagittal, including extreme maxillary overjet, mandibular overjet, distal molar occlusion (distocclusion), and mesial molar occlusion (mesiocclusion); vertical, including frontal open bite, lateral open bite, and frontal deep bite; and transverse, including crossbite and scissors bite. Finally, spacing conditions consist of crowding and spacing (diastema) situations.

Some types of malocclusion have a greater tendency to persist during dentition development and the transition to permanent dentition, such as distocclusion7 and mesiocclusion.8 On the other hand, other types of malocclusion may undergo spontaneous corrections during the child’s development, namely, anterior open bite and posterior crossbite.7

Nonetheless, several studies indicate that having a malocclusion in the primary dentition is a determining factor for having it in the permanent dentition, increasing the likelihood of needing orthodontic treatment.9-11 Studies on the prevalence of malocclusion in Portuguese children populations are scarce but have shown a considerable prevalence of these oral conditions in the primary dentition.12,13

Since malocclusion can be related to some oral behaviors, namely non-nutritive sucking habits,14,15 early diagnosis and intervention are essential for its control. Knowing the distribution and factors associated with malocclusion in the primary dentition will help understand the disease at those ages and plan and implement preventive measures. The present study aims to contribute to the knowledge of malocclusion in the

Portuguese preschool population’s primary dentition. Its objectives are as follows: 1) To study the prevalence of malocclusion in the primary dentition of a Portuguese population; 2) To characterize non-nutritive sucking habits in the same population; 3) To relate sociodemographic factors, dental caries, and non-nutritive sucking habits with the presence of malocclusion in the primary dentition.

Material and methods

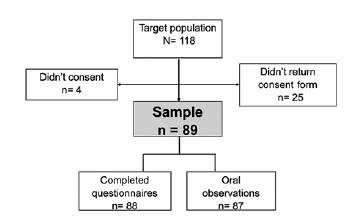

A cross-sectional study was carried out as part of a larger project, which was approved by the ethics committee of the Facrev ulty of Dental Medicine of the University of Lisbon. The targetpopulation consisted of preschool-aged children who attended four kindergartens in Alvalade, Lisbon, during the school year of 2017/2018. The study sample was non-probabilistic and included a private institution, a public institution, and two social solidarity private institutions (IPSSs). All participating institutions authorized the study and data collection on their premises. The study included all children from the selected institutions aged between 3 and 5 years old whose parents or legal guardians gave their consent and who verbally agreed to participate. Children who were under or had undergone orthodontic/orthopedic treatment and those with at least one permanent tooth were excluded.

Data was collected through a questionnaire and an intraoral examination. The questionnaire was developed for the study based on a literature review.3,5,7,16 Before its application in the study, the questionnaire was evaluated by a panel of four experts in oral-health epidemiological studies experienced in the study area and was then pre-tested in a few parents of preschool children. The questionnaire was applied to the children’s parents or legal guardians and collected sociodemographic data and information on non-nutritive sucking habits.

The intraoral examination included an assessment of occlusal characteristics and diagnosis of malocclusion according to the criteria defined by Bjöerk et al.6 for the primary dentition and by the Fédèration Dentaire Internationale in 1973, as adapted by Zhou et al.16. The occlusal evaluation was performed in the position of maximum intercuspation, and measurements were performed with an accuracy within 0.5 mm using a graduated periodontal probe. Based on the occlusal measurements, malocclusion was classified as sagittal (mesiocclusion, edge-to-edge, or distocclusion) or vertical (deep overbite or open bite). Transverse malocclusions were evaluated and classified into posterior crossbite, posterior scissors bite, and crowding. Finally, dental caries were assessed according to the International Caries Detection and Assessment System II (ICDAS II).17 All intraoral examinations were conducted by the same trained investigator (dentist) in the kindergarten facilities using natural and artificial lighting, a periodontal probe, and an intraoral mirror.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS - Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017). It included descriptive statistics and inferential analysis using the chi-squared test (α=0.05). Malocclusion prevalence estimation considered all children with at least one of the situations described above. When a study participant had information missing due to an unanswered question or the impossibility of performing the corresponding procedures, the remaining variables collected were still considered for the statistical analysis. Thus, the “n” may differ between the collected variables.

Results

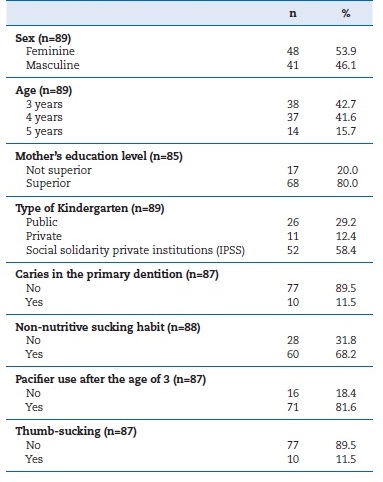

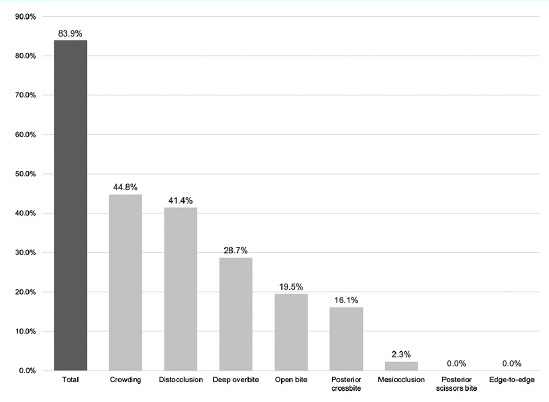

The sample included 89 children (Figure 1), corresponding to a participation rate of 75.4%. Table 1 shows the sample’s distribution by sociodemographic variables, dental caries, and non-nutritive sucking habits. Non-nutritive sucking habits were somewhat frequent, with 68.2% of children having at least one. Malocclusion prevalence in the primary dentition was 83.9% (n=73). The most frequent type of malocclusion was crowding, followed by distocclusion. No cases of edge-to-edge or posterior scissors bites were observed (Figure 2). The mean overbite was 1.7 mm (sd=2.5), and the mean overjet was 2.9mm (sd=2.1). Table 2 relates the types of malocclusion with sociodemographic factors, dental caries, and non-nutritive sucking habits. Statistically significant associations were found between age and the presence of distocclusion (p=0.002) and malocclusion (p<0.001). A higher mother’s level of education was associated with a higher percentage of crowding (p=0.01). Caries were most frequent in children with distocclusion (p=0.04).

Table 2 Sociodemographic factors and non-nutritive sucking habits associated with the prevalence of malocclusion.

MO - mesiocclusion; DO - distocclusion; PCB - posterior crossbite; Cr - crowding; OpB - open bite; DOvB - deep overbite; IPSS - social solidarity private institutions.

p values indicated in bold have statistically significant differences (p<0.05).

Pacifier use after the age of three was more frequently associated with distocclusion (p=0.01) and open bite (p=0.001) and inversely related to deep overbite (p=0.02). The thumb-sucking habit was associated with open bite (p=0.02).

Discussion

Malocclusion is a worldwide public health problem and, for this reason, has been widely studied over the years.2-4,9,11,18Most of the studies include permanent or mixed dentitions, and the studies on primary dentition usually focus on the repercussions of oral health-related behaviors in one particular kind of malocclusion. Some situations of malocclusion in the primary dentition spontaneously regress with the transition to the permanent dentition,7 but others remain, requiring therapeutic intervention. Thus, early detection and intervention in harmful behaviors are extremely important for preventing severe situations.

In the present study, “malocclusion” was defined as the presence of at least one type of malocclusion, which resulted in a very high prevalence (83.9%). The literature also reports generally high malocclusion prevalence values in the primary dentition, varying between a minimum of 53% and a maximum of 81.4%.7,13,16,19,20 This wide range may be related to diferente criteria used to classify malocclusion and to the influence of environmental factors and different cultural and behavioral patterns of the studied populations.

The literature reports the anterior open bite as the most frequent type of malocclusion.3,21 Contrarily, the most frequente type of malocclusion in the present study was crowding (44.8%), followed by distocclusion (41.4%) and deep overbite (28.7%). A similar study also reported crowding as the most frequent type of malocclusion, with a prevalence of 23%.18 Another study22 observed an 11.1% prevalence of crowding in the primary dentition in one or both dental arches but stated that crowding in this dentition does not determine malocclusion, contrary to crowding in a mixed or permanent dentition.

Regarding distocclusion, it was highly frequent in some studies16,18,20 and rarely found in others.23,24 In turn, the literature reveals a high prevalence of deep overbite.13,3

In the present study, older children generally showed a lower prevalence of malocclusion, with decreasing values from three to four years old and, with greater relevance, from four to five years old. This result agrees with the reported self-correcting tendency of some types of malocclusion.25 This natural correction may be associated with correcting behaviors such as pacifier use and other non-nutritive sucking habits. A study found that after removing the pacifier habit in 4-year-old children, the frequency of malocclusion and changes in breathing and speech decreased significantly.15 Healthcare professionals who follow preschool-aged children should consider this natural correction while bearing in mind that early intervention in these habits is essential.

Campos et al.26 did not find a statistically significant association between malocclusion and the mother’s level of education. The present study only found this association in crowding, with a higher prevalence of crowding among children whose mothers had a higher education level. The mother’s educational level is most likely a confounding variable since there seems to be no biological or physiological explanation for this relationship. On the other hand, the relation between malocclusion prevalence in the primary dentition and socioeconomic factors has dissimilar results in the literature.27 Some studies found no association between these variables,28 others found a higher prevalence of malocclusion in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic levels,29 and others an inverse association.19 The differences between these studies’ results can be explained by several factors, such as methodological differences or cultural characteristics of the populations studied.

The present study found a significant association between the presence of dental caries and distocclusion. A study in Chinese children16 and another in Tanzania also described this significant association.30

Non-nutritive sucking habits were frequent in this study.

According to Tomita,25 using a pacifier after three years of age becomes a childish regression behavior with the potential to generate occlusion anomalies. Anterior open bite and posterior crossbite are the types of malocclusion most commonly associated with prolonged oral habits.18 In the present study, there was an influence of non-nutritive sucking habits on children’s occlusion, indicating that these habits were directly associated with the presence of anterior open bite and, on the other hand, indirectly associated with the presence of deep overbite. Other authors also found an association between non-nutritive sucking habits, such as using pacifiers or digital or object sucking, and the presence of some form of malocclusion.3,4,25,26

Although oral habits can convey a sense of security and comfort, an early diagnosis and timely correction of these harmful habits are important to prevent them from significantly impacting occlusion, thus causing more serious and costly situations and decreasing the child’s quality of life.

Therefore, early implementation of oral-health promotion measures is essential, ideally in the final period of pregnancy and during the first year of life. Healthcare professionals who care for children of these ages, namely family doctors, pediatricians, nurses, oral hygienists, and dentists, should be involved in promoting and educating the parents. In cases where non-nutritive sucking habits persist after four years of age, the protocol proposed by Shah et al.31 could be applied, including psychological therapies, non-orthodontic interventions, and, in more severe cases, orthodontic interventions.

The present study has some limitations regarding the sample’s characteristics and small size. However, given the scarce data on malocclusion in the primary dentition in the Portuguese population, this study contributes to the knowledge of malocclusion prevalence and its associated factors. More studies are needed in larger and more representative populations, where other factors possibly associated with malocclusion in the primary dentition can be studied.

Conclusions

The prevalence of malocclusion in the primary dentition was high, with the most common type of malocclusion being crowding, followed by distocclusion and deep overbite. The child’s age and the mother’s education level were associated with the presence of malocclusion, with a trend to decrease as age increases and the mother’s level of education decreases. In general, non-nutritive sucking habits revealed a direct association with a higher prevalence of malocclusion.