Introduction

Ramsay-Hunt syndrome (RHS) is a rare infectious disease associated with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) or the human herpesvirus type 3 (HHV-3) that was described by James Ramsay Hunt in 1907.1,2Despite its rare incidence of five cases per 100,000 people, RHS is considered the second most common cause of peripheral facial palsy (PFP), after Bell’s palsy.3 In addition to PFP, the symptoms and signs of the disease may include flu-like symptoms, such as inner ear dysfunction, periauricular pain, and rash, as well as herpetiform vesicles that can reach the ear pinna, external auditory canal, facial skin, tongue, hard palate, buccal mucosa, neck, and larynx.1,3 RHS has no gender preference and generally affects individuals between 20 and 30 years old.1,2PFP usually occurs due to the reactivation of the VZV that remains latent in the sensory ganglion, leading to inflammation, edema, and consequente compression of the VII cranial nerve.4-6

Patients who develop PFP experience asymmetry and impairment of facial muscle mobility, leading to difficulty speaking and eating.7-9Besides involuntary muscle contractions of the eyes, nose, forehead, and lips, excessive tearing can also be observed.9 Thus, the disease significantly affects the patient’s ability to perform daily activities, leading to a decline in quality of life.9 Clinical scales can be used to assess the evolution and severity of PFP, plan the most appropriate therapy, and establish a prognosis.9 The House-Brackmann scale,10 based on the absence or presence of facial movements, is the most employed scale.9,10

There is still no consensus on the most appropriate treatment for PFP. The drug therapy consists mainly of prescribing corticosteroids - potent anti-inflammatory medication that reduces nerve swelling - and antivirals. Other adjuvant treatments that can be employed include electrotherapy, facial massage, acupuncture, facial expression exercises, and photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT).11-15

PBMT, or low-level laser therapy, is a non-invasive and painless treatment that acts on the regeneration of neurons, increases microcirculation, activates angiogenesis, and heals the damaged peripheral nerves in both sensory and motor fibers.11,15-18 The absorption of photons by laser radiation is necessary to produce a photobiological response, particularly in the context of photobiomodulation. Chromophores - molecules capable of absorbing light at specific wavelengths - act as initial photoreceptors.

It has been suggested that mitochondria are highly sensitive to visible and near-infrared light in photobiomodulation. This light absorption by mitochondria can lead to various effects, such as increased production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), enhanced DNA synthesis, modulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide species (NOS), as well as induction of transcription factors. Additionally, the absorbed energy can be transferred to other molecules, resulting in chemical reactions without significant temperature changes in the surrounding tissue.

At specific wavelengths, PBMT can activate native componentes within cells, potentially leading to alterations in biochemical reactions and cellular metabolism.15,19Furthermore, it modulates the inflammatory process, can be associated with other therapies, and is a widely used therapeutic modality in cases of PFP.

This case report describes a fast and complete recovery of facial palsy in Ramsay-Hunt disease treated exclusively with PBMT.

Case Report

A 26-year-old female patient sought medical care with a complaint of flu-like symptoms. In the anamnesis, she reported having been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) five years earlier, in good general condition, and controlling the disease with hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/day) since then. Due to the emerging Covid-19 pandemic and the suspicion of viral infection caused by Sars-Cov-2, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was required (with a negative result) and analgesics and multivitamins were prescribed. Despite therapy and the negative Covid-19 test result, the patient presented worsening respiratory symptoms and sought emergency medical care. She was prescribed loratadine, ambroxol, analgesics, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and did a second diagnostic PCR test for Sars-Cov-2 (also negative). With the progression of symptoms, the patient started to present otalgia, and at the third medical visit, an antibiotic (amoxicillin 500 mg every 8 hours for 10 days) was prescribed to replace the previously prescribed NSAID. Twenty-three days after the symptoms’ onset, she presented a lack of mobility of the muscles on the right side of the face and facial asymmetry, all clinically compatible with PFP.

Considering the patient’s signs and symptoms, the final diagnosis was RHS. The disease and its symptoms were managed with acyclovir (800 mg/5x a day), prednisone (80 mg/day for 7 days), and physiotherapy sessions. About 10 days after the end of the drug treatment and after four sessions of physiotherapy, no significant clinical response was observed. The patient had PFP for more than 17 days and reported no signs of improvement.

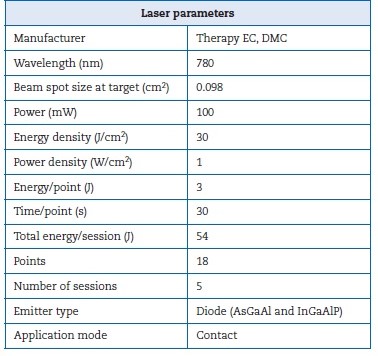

Due to the concern with PFP and aesthetics, the patient sought an Oral Medicine team for an evaluation. The extraoral physical examination identified the PFP associated with cranial nerve VII affecting the frontal, infraorbital, and buccal ramifications, reaching three-thirds of the face on the right side. Her PFP was classified as grade IV, which is moderately severe according to the House-Brackmann scale (Figure 1). In addition, the patient reported dysgeusia and dry eyes. PBMT was the only treatment proposed by the Oral Medicine team to manage the PFP. The parameters used in the PBMT are described in Table 1; the irradiation points are detailed in Figure 2. A significant improvement in the House-Brackmann scale was observed in the fourth PBMT session.21

Figure 1 Facial aspect of the patient with peripheral facial palsy before photobiomodulation therapy

After five sessions (performed twice a week for three weeks), the patient presented complete regression of the PFP and regained facial movement and expressions (Figure 3). The recovery from dysgeusia and eye dryness was gradual, accompanying the PFP improvement. The patient is still being monitored by the Oral Medicine team. Even after about 18 months of the manifestation, she has not presented new episodes or recurrence of PFP and RHS.

Discussion and conclusions

Currently, there is no consensus on the most appropriate treatment for RHS. The general recommendation is a combined prescription of antivirals and corticosteroids. However, some studies argue that there is insufficient evidence regarding antiviral agents’ beneficial effects on this condition.19In addition, corticosteroids are associated with several wellknown adverse effects.19

In 2016, Monsanto et al.1 reviewed the prognosis of facial palsy on RHS, considering the different treatments proposed in the literature. Overall, patients with RHS achieved a high rate of complete recovery of the facial nerve function (70.4%) after the different proposed treatments - mostly corticosteroids and antiviral drugs. Dosage and period of treatment varied greatly among studies. Clinical data such as age, associated metabolic diseases, impairment of the cochleovestibular or other cranial nerves, oropharynx lesions, dry eyes, and lagophthalmos must be assessed at the initial physical examination since they suggest a worse prognosis of facial palsy secondary to RHS.1

Lasting PFP that does not improve with conventional therapy is difficult to manage because it impacts the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, other therapeutic approaches, such as botulinum toxin, acupuncture, electrical stimulation, and PBMT, can be used to avoid significant sequelae.11,15-18,20PBMT is a good therapeutic option as it is painless, has no adverse effects, and can be associated with other treatments.11,15-18,20It acts on microcirculation, stimulating nerve regeneration and, consequently, accelerates the PFP’s recovery process.11,15-18,20 Although PBMT is associated with a shorter recovery period than drug therapies, a 3-month-long treatment may be necessary.[11]

No articles describing PBMT as a treatment for PFP in RHS were found in recent literature. On the other hand, several studies indicate PBMT as a therapy for Bell’s palsy.11,15-18 Bell’s palsy is another form of PFP associated with the facial nerve that is more common and has higher recovery rates than RHS.7,8 Despite not having a well-defined cause, Bell’s palsy may be associated with tumors, trauma, infections, or neurological and immunological diseases. Pregnancy and diabetes are also risk factors for Bell’s palsy, and the reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus is regarded as the main cause of facial nerve edema.7,8

A systematic review study suggested that low-level laser therapy (830 nm wavelength and 80 J of total energy per session for 6 weeks) could effectively improve patients with subacute Bell’s palsy.16 As RHS is also a form of facial paralysis, PBMT can be a promising treatment. In the present study’s patient, it quickly provided good clinical results.

Some authors report that PFP’s severity and prognosis may be related to immunity and adjacent diseases of the patient.7,8Our patient had been diagnosed with SLE, which may be associated with the onset of the condition. However, it was not na obstacle to a good recovery using PBMT after not having shown significant improvement with drug therapy and physiotherapy.

In this case, complete and fast clinical recovery of facial movement was achieved solely using PBMT, thus avoiding irreversible sequelae.20 This result suggests that PBMT can be an effective treatment option for managing PFP associated with RHS. PFP causes asymmetry of the face. The prognosis may be fair, with complete repair in most cases. This case presented a complete PFP recovery with only five sessions of PBMT, which is a much faster response than usually reported in Bell’s palsy.

The PBMT protocol used was an effective therapy for PFP associated with RHS, and the early complete recovery impacted the patient’s quality of life.