Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.12 no.1 Coimbra mar. 2018

ORIGINAL STUDY/ESTUDO ORIGINAL

Surgical staging and endometrial carcinoma: preoperative magnetic resonance or intra-operative pathological exam, how best to proceed?

Carcinoma do endométrio e estadiamento cirúrgico: ressonância magnética ou estudo extemporâneo?

Fernanda Santos*, Rafaela Pires**, Isabel Henriques***, Fernanda Águas***

Serviço de Ginecologia B do Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra

*Interna de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, Centro Hospitalar de Leiria

**Interna de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, Serviço de Ginecologia B do Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra

***Especialista de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra - Divisão B, Serviço de Ginecologia

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Overview: Endometrial cancer is a common gynecological malignancy, diagnosed at stage I in 80% of cases. In the absence of contra-indication, staging is surgical. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is not recommended in low risk endometrial cancers. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful to predict the depth of myometrial invasion in the preoperative assessment, but intra-operative pathological exam could also be used.

Aim: To analyze the concordance between final histological exam and pre-operative MRI or intra-operative pathological exam.

Study Design: Cross-Sectional Study

Methods: It was performed a cross-sectional study of 145 women diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma, in a tertiary clinical center, from January 2010 to December 2015. It was analyzed 60 cases, the ones submitted to MRI and extemporaneous exam. Statistical analysis was performed by STATA 13.1.

Results: Sixty cases of endometrial cancers have been rated using MRI and intraoperative histological exam. The observed concordance (MRI versus final invasion) was 81%, with kappa index of 0.54 (moderate concordance). MRI has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 80% (AUC:0.84). Adjusting for prevalence, MRI negative predictive value (NPV) was 95% and positive predictive value (PPV) was 55%.

When compared to MRI, the extemporaneous exam demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity (Sensitivity:91%; specificity:93%, AUC:0.92; PPV: 77%, NPV: 98%).

The Kappa index was 0.79 (substantial concordance). Comparing the two diagnostic tools, the extemporaneous exam was superior (p= 0.04).

Conclusion: Extemporaneous exam has demonstrated diagnostic superiority

Keywords: Endometrial neoplasms; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; Neoplasm staging; Frozen sections; ROC curve.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most frequent gynecological neoplasia in developed countries1. Incidence rates have regional variations, but mortality rates are generally low. In Portugal, the incidence in 2014 was 17.8 and mortality 3.8 per 100000 inhabitants2. More than 90% of endometrial cancers are identified in women over the age of 50, however, approximately 4% are younger than 40 years, which makes issues related to preservation of fertility remain relevant3.

In order to stratify the risk of disease, endometrial carcinomas were divided into two types, type 1 and 2. Type 1 carcinomas, also called endometrioids, are the most frequent (80-90%) and those with a more favorable prognosis. It is recognized the association with precursor lesions (atypical hyperplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia of the endometrium) and mutations of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN and Kras. They are estrogen-dependent tumors, usually developing in environments subject to prolonged estrogen (endogenous or exogenous) insufficiently counterbalanced by progesterone. Other risk factors such as obesity, nulliparity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, exposure to tamoxifen, and Lynch or Cowden syndromes are also identified. On the other hand, type 2 carcinomas are less frequent, with a more aggressive behavior, affecting older women with atrophic endometrium and histologically characterized by non-endometrioid subtypes, such as serous carcinomas, clear cells or undifferentiated3.

Although useful, this division is restricted, especially regarding molecular heterogeneity and pathological risk. In molecular terms, “The Cancer Genome Atlas” (TCGA) research group stratified 4 subtypes according to the type and number of mutations identified4. On what concerns pathological risk, the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) separated these neoplasias in three large groups. The criteria adopted for this separation were 2009 FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) staging and histology. Thus, the groups are described as: 1) low risk, including endometrioid carcinomas, type IA G1 or G2, 2) intermediate risk, including endometrioids IA G3, or IB G1 or G2 and 3) high risk, the endometrioid carcinomas IB G3, IA-IB non-endometrioids or stage I with lymphovascular invasion.

The staging of endometrial carcinoma is surgical and in the early stages, surgery may be curative4 . High surgical risk and locoregional disease invasion (parametrial and/or adjacent organs), are examples of surgical contraindication5. In order to staging be considered complete, it should include extrafascial hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy, biopsy of suspicious lesions, and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy4,5. This procedure is currently reserved for high-risk carcinomas, since it may be associated with the development of complications and also for its therapeutic benefits that are not yet consensual. Kim et al, carried out a meta-analysis with 16 995 patients, and concluded that systematic lymphadenectomy, defined as the removal of more than 10 lymph nodes, only has an impact on overall survival in the presence of risk factors6. Thereby, the importance of a correct preoperative evaluation is maintained and the need to implement measures that stratify patients is reinforced. Non endometroid histologic subtypes, G3 differentiation, tumor of more than 2 cm and deep myometrial invasion (greater than or equal to 50%) are recognized as risk factors for nodal metastasis. The presence of any of these is indication for lymphadenectomy4-6. In the early stages, preoperative or intraoperative methods have been developed and applied in the stratification of nodal metastasis risk. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is regarded by many authors to be the most effective imaging modality (sensitivity 80-90%) in the evaluation of myometrial and parametrial invasion. Extemporaneous histological study, despite the inconsistent findings, is also useful in evaluating the depth of invasion and degree of differentiation7. According to ESMO, European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) and European Society for Radiotherapy & Oncology (ESTRO) consensus, the myometrial invasion should be assessed by one of the techniques: expert ultrasound and/or MRI and/or intra-operative pathological examination (level of evidence: IV, Strength of recommendation: A)4. Finally, sentinel lymph node biopsy, although considered a promising approach, is still limited by variable detection levels and difficulties in approaching the identification of low-volume metastases (micrometastases or isolated tumor cells)8.

So, the main objective of the present study will be to evaluate the agreement between the depth of myometrial invasion, identified in MRI or extemporaneous exam and that identified in the final histology.

Methods

It was performed a cross-sectional, retrospective and analytical study of 145 cases of endometrial carcinomas diagnosed in the B Gynecology department of Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (CHUC) from January 2010 to December 2015. Carcinossarcomas were excluded. Seventy-two percent of the endometrial carcinoma cases were staged as stage I. From 145 cases, 60 were analyzed, because only these were submitted to both exams under study (MRI and extemporaneous histology). The 60 cases were considered representative of the sample, because they illustrate more than 55% of those that could be submitted to both exams. The data were obtained from the clinical processes.

This study was approved by local ethical committee and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

The following variables were analyzed: age of diagnosis, body mass index (BMI-kg/m2), parity, menopause, arterial hypertension, reasons for being admitted to the hospital, diagnostic method, preoperative Ca125 levels, preoperative MRI, myometrial imaging invasion on MRI (inferior/superior or equal to 50%), surgery, extemporaneous exam and histological myometrial invasion (lower/higher or equal to 50%), histological subtypes (according to World Health Organization (WHO) classification), cell differentiation, final depth myometrium invasion , 2009 FIGO staging, adjuvant treatments and current status of follow-up.

More than 90% of MRI, were performed at the CHUC imaging department. Occasionally, records of exams performed abroad have been identified. The described technique is reported only from 2014. Thus, the images were obtained by coronal SSh, axial, sagittal and coronal T2, axial T2 SPAIR, axial and sagittal THRIVE SPAIR sequences, before and after the intravenous administration of gadobutrol and also by T1 SPIR axial after contrast. The extemporaneous histological study was performed at the pathological anatomy department of CHUC, by macroscopic analysis of the piece and by microscopic observation after frozen section and rapid staining with hematoxylin and eosin. The area selected for sectioning was the one where macroscopically larger myometrial invasion was apparent. The cuts were performed with cryostat, originating 5mm thick samples.

Treatment and monitoring of patients were performed according to gynecological cancer consensus, adapted to the year under analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA program (version 13.1), with a statistically significant result if p <0.05 and a 95% confidence level. To evaluate the relationship between nominal variables, Fisher's exact or chi-square test were used, to compare measures of central tendency were used student's t-test or Wilcoxon's test (according to the presence or absence of normal distribution). The adjustment of confounding factors was done through the application of a logistic regression. The concordance was analyzed by Kappa index calculation, which consists of a statistical tool that measures the degree of agreement beyond what would be expected by simple chance. The kappa values generally range from 0-1 (0: absence of agreement and 1: perfect agreement). According to Landis and Koch, it is considered moderate agreement if kappa values between 0.41 and 0.60 and substantial if kappa values between 0.61 and 0.809. The comparison of diagnostic methods was performed by comparing models of ROC (Receiver operating characteristic) curves.

Results

One hundred and forty-five cases were evaluated, of which only 60 were submitted to the complementary tests under study (MRI and extemporaneous study). From these 60 patients, 73% (n = 44) were identified as stage IA, 18% (n = 11) stage IB, 5% (n = 3) stage II and 3% (n = 2) stage IIIc1. One of the IIIc1 cases was MRI detected as IA, and it was the extemporaneous study that led to lymphadenectomy. In the second IIIc1 case, both complementary exams indicated deep myometrial invasion.

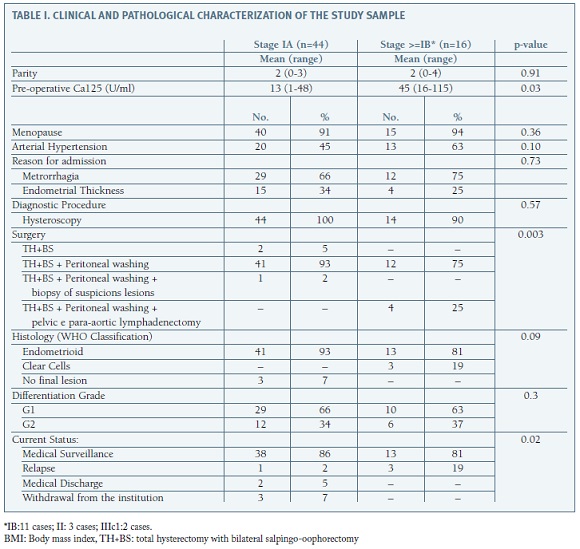

Analyzing the demographic characteristics, retrospectively evaluated and academically separated in a population with a final stage IA or equal/superior than IB, we identified mostly menopausal patients, with an average age of 67 years, admitted by metrorrhagia and submitted to initial evaluation by hysteroscopy (Table I).

A statistically significance was observed in relation to the preoperative Ca125 values, being higher in patients with more advanced disease stages (p = 0.03).

Well differentiated endometrioid lesions predominated. Clear cell carcinomas were identified in patients with late stage IB or II.

To date, 87% (n = 52) of the patients are under surveillance, 3% (n = 2) have completed the recommended period for follow-up in a differentiated service and 5% (n = 3) have left the institution. (Table I) Four relapses were identified. One at stage IA at the end of 6 months, (diagnosed at the level of the vaginal cuff) and two at IB stages, at the end of 53 and 57 months of follow-up, respectively. These three cases were all clear cell carcinomas. The last relapse occurred at stage II at the end of 16 months of follow-up. It was characterized as endometrioid, with moderate differentiation and lymphovascular invasion. Thus, the mean disease-free interval was 33 months and the disease-free survival rate was 93%. No cases of death were identified.

Adjusting to age, histology and staging, we found a statistically significant relationship between myometrial invasion higher or equal to 50% on MRI imaging and the same finding in the final histology (p: 0.004, OR:39;3.2-460.1). The same was analyzed for the extemporaneous study, and an equally significant relationship was also identified (p <0.001 OR:187; 95% CI (15-2319.0)).

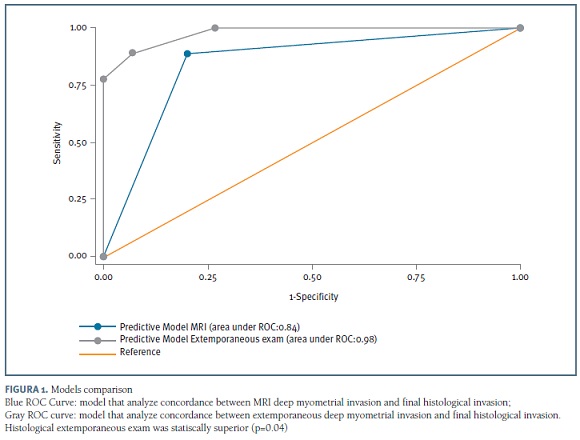

The concordance between the MRI imaging at early stages and the final histological invasion was analyzed. A concordance of 81% was identified, with a Kappa index of 0.54 (moderate agreement). MRI demonstrate diagnostic sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 80% (AUC: 0.84). Adjusting for disease prevalence, in 95% of cases MRI was truly negative and in 55% it was truly positive. False negatives (n=8) were identified in studies conducted prior to 2012. Sixty three percent of false negative were clear cell carcinomas and 50% had degrees of differentiation equal to 2. Regarding the extemporaneous study, sensitivity and specificity was superior to MRI (S = 91%, E = 93%, AUC: 0.92). The extemporaneous was truly negative at 98% and truly positive at 77%. The Kappa index was 0.79 (substantial agreement). Comparing the two models of study (MRI or Extemporaneous exam versus final myometrial invasion), extemporaneous exam has a superior and statistical significant agreement (p = 0.04) (Figure 1).

Discussion

According to this study, we found that, in comparison with preoperative MRI, the extemporaneous exam had higher agreement (substantial Kappa index), better sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive value.

In the multivariate analysis, we verified that the risk to identify a final deep myometrial invasion by MRI was 39 times (p: 0.004, OR: 39; 95% CI (3.2-460.1)), and by extemporaneous exam was 187 times higher (p <0.001 OR: 187; 95% CI (15-2319.0)). However, although tempted to conclude by the superiority of the extemporaneous, it is something that becomes statistically impossible. This is because when we have a wide confidence intervals as the one found, the odds ratio obtained may be so inaccurate that makes any kind of interpretation impracticable10. It was for this reason that we decided to elaborate a statistical model (two logistic regressions), in order to test the difference between areas of ROC curves (identification of myometrial invasion on MRI or extemporaneous exam versus final myometrial invasion). Thus, it was possible to conclude that the extemporaneous study was in fact superior in the predictive analysis of the final myometrial invasion (p = 0.04). (Figure 1)

Blue ROC Curve: model that analyze concordance between MRI deep myometrial invasion and final histological invasion; Gray ROC curve: model that analyze concordance between extemporaneous deep myometrial invasion and final histological invasion. Histological extemporaneous exam was statiscally superior (p=0.04)

Several published studies assess the capacity of MRI or extemporaneous study to determine myometrial invasion in the context of endometrial neoplasia11. According to recent studies, the diagnostic sensitivity of MRI is approximately 80 to 90% (variable from 57 to 100%) and the specificity is 75 to 90%7,12. Data that is similar to our results, since we identified a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 80%. Despite variability and poorly consistent results, overall, higher sensitivity and diagnostic specificity (40% to 98%, 53% to 98%, respectively) are attributed to an extemporaneous study. We also found higher sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive value for the extemporaneous exam (S = 91%, E = 93%, negative predictive value = 98% and positive predictive value= 77%). Some authors identify disagreement with the final histology. Leitão et al analyzed 482 women with adenocarcinoma endometrioid G1 and found that in 15% of these the degree of final differentiation was higher than that obtained by the extemporaneous study13. On the other hand, some authors argue that bias is frequently introduced when histology is analyzed by the same anatomopathologist, once he has previous knowledge of what he has identified as extemporaneous. They conclude that there is a greater risk of underestimating the disease and therefore not treating patients properly11 . We found final grade disagreement in 16% of cases and histological disagreement only in 5% of cases (the three cases of clear cell carcinomas were only found on final histology).

Although the study presented resulted from a rigorous analysis, the scarce number of cases analyzed limits the extrapolation of results. Another major inherent limitation is the fact that it is a retrospective analysis, which is endowed with a lower level of evidence and greater susceptibility to information or selection bias. We also identify the limitations introduced by the fact that imaging tests were performed by different operators and different techniques throughout the study period. Also, the extemporaneous and definitive histological studies were alternately analyzed by the same ones, as well as by different anatomopathologists, which potentially inculcates the occurrence of bias. Finally, it is necessary to mention the technical, scientific and theoretical development that took place over the period of time analyzed. As an example, we have the oncology national consensus, published in 2010, updated in 2013 and recently in 2016.

However, the study also has strengths. The clinical relevance and usefulness of the analyzed question, the inexpensive execution and the statistical study, which took into account the presence of potential confounding factors, which were analyzed by means of adjustment techniques.

Finally, we conclude, it is not possible to dispense any of the tests alone, despite the superiority identified for the extemporaneous study. However, in order to overcome the identified limitations, it will be useful to carry out a prospective, multicenter study with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria and well-defined execution techniques. In this way, the evidence will be superior and the conclusions will certainly be endowed with greater scientific accuracy.

REFERENCES

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer. 2014;136(5):E359-E386. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr (cited 20 December 2016). [ Links ]

2. Portugal - Doenças Oncológicas em números - 2015. Direção-Geral da Saúde, 2016. [ Links ]

3. Chen L., Berek Jonathan. Endometrial carcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors [Internet]. Uptodate.com. 2016 Available at: http://www.uptodate.com (cited 20 December 2016). [ Links ]

4. Dursun P, Ayhan A. Gynecologic Oncologist Perspective About ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(4):826-831. [ Links ]

5. Cancro Ginecológico, Consensos Nacionais 2016. [ Links ]

6. Ghanem A, Khan N, Mahan M, Ibrahim A, Buekers T. The Impact of Lymphadenectomy on Survival Endpoints in Women with Early Stage Uterine Endometrioid Carcinoma: A Matched Analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2017;210:225-230. [ Links ]

7. Plaxe S. Endometrial carcinoma: Pretreatment evaluation, staging, and surgical treatment [Internet]. Outubro 2016. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com (cited 20 December 2016). [ Links ]

8. Khoury-collado F., St. Clair C., Aburustum N. Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Endometrial Cancer: An Update. The Oncologist, 2016;21:461-466. [ Links ]

9. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159-174. [ Links ]

10. Mario A. Cleves. From the help desk: Comparing areas under receiver operating characteristic curves from two or more probit or logit models, The Stata Journal. 2002; 2 (3),301-313.

11. Tanaka T, Terai Y, Ono Y, Fujiwara S, Tanaka Y, Sasaki H et al. Preoperative MRI and Intraoperative Frozen Section Diagnosis of Myometrial Invasion In Patients With Endometrial Cancer. Int J of Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(5):879-883. [ Links ]

12. Gallego J, Porta A, Pardo M, Fernández C. Evaluation of myometrial invasion in endometrial cancer: comparison of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance and intraoperative frozen sections. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39(5):1021-1026. [ Links ]

13. Leitao M, Kehoe S, Barakat R, Alektiar K, Gattoc L, Rabbitt C et al. Accuracy of preoperative endometrial sampling diagnosis of FIGO grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(2):244-248. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Fernanda Santos

Pombal, Portugal

E-mail: fernandapatricia.santos@yahoo.com

Recebido em: 25/06/2017

Aceite para publicação: 23/08/2017