Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.12 no.1 Coimbra mar. 2018

CASE REPORT/CASO CLÍNICO

Parasitic myoma: a rare presentation of a common disease

Mioma parasita: forma rara de apresentação de uma entidade comum

Sofia Aguilar*, Catarina Vasconcelos*, Lina Redondo**, Ana Fatela**

Maternidade Dr. Alfredo da Costa - Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central

*Interna da Especialidade de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia

**Assistente Graduado de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Parasitic myomas are a rare form of uterine leiomyomas. Distinction from other abdominal masses may be difficult, due to parasitic leiomyomas' variable anatomic locations and clinical manifestations.

We describe the case of a 45 years-old woman, presenting with abdominal pain and a large pelvic mass that turned out to be a parasitic myoma at surgical assessment.

Histological analysis confirmed the intraoperative suspicion.

We intend to bring awareness to the inclusion of this condition in the differential diagnosis of pelvic masses, especially in women with risk factors for parasitic myomas, such as previous surgery for uterine fibromyomatosis or concomitant uterine myomas.

Keywords: Parasitic myoma

Introduction

Uterine leiomyomas are the most common benign pelvic tumors in females1, affecting 20-50% of reproductive aged women2. Occasionally they can be found at extrauterine sites, through haematogenous dissemination, parasitic origin or independent growth from other muscular tissues3,4.

Parasitic myomas, a rare form of uterine leiomyomas, can occur spontaneously or after a surgical intervention for uterine myomatoses. It is believed that spontaneous parasitic myomas result from pedunculated subserosal uterine myomas, which loose their uterine connection, acquiring new vascular supply from adjacent organs4,5. Iatrogenic parasitic myomas emerge from extrauterine implantation and independent growth of fibroid fragments that are seeded during myoma manipulation or unconfined morcelation in a myomectomy or hysterectomy procedure2,5. Laparoscopy apparently carries a greater risk compared to open surgery, maybe because of a greater employment of morcellation techniques, use of power morcellators resulting in tiny fibroid fragments (easily unrecognised) and a more limited capacity to detected intra-abdominal myoma portions and to wash out the field2,6-8.

Our understanding of this clinical entity is limited to a few case reports and small case series. However, over the last years, reports of iatrogenic parasitic myomas increased, due to the widespread of laparoscopic surgery1, which resorts to morcellation techniques, believed to predispose to parasitic myoma formation2,4. Consequently, it is our understating that clinics need to be more aware of this diagnostic possibility.

Case report

A 45-year-old female patient presented at the emergency room complaining of pelvic pain, lasting for 3 days. No fever, weight loss, abnormal vaginal discharge, urinary, gastrointestinal or other symptoms were present, with the exception of constipation. Her last menses was 14 days before and she had a history of chronic abnormal uterine bleeding due to uterine fibromyomatoses, associated with anemia, a condition already under routine hospital follow-up. She used condom plus spermicide for contraception. The patient's obstetrical history included one term vaginal delivery and one spontaneous miscarriage. Other than uterine myomas and an appendicectomy many years ago, she denied any relevant diseases or previous surgeries; she was also not taking any medication.

At physical examination the patient was alert, oriented, hydrated, had normal vital signs and no pallor was present. Abdomen was soft but tender on deep palpation of the suprapubic region; guarding, rigidity, and rebound were all absent. Gynaecological exam revealed no vulvar, vaginal or cervical lesions and the vaginal discharge was normal, but the uterus was enlarged, irregular in shape and painful at mobilization during bimanual palpation.

Laboratory results documented: normocytic normochromic anemia (Hb=9.9 g/dL) and an elevated C-reactive protein (=18,3 mg/L for a normal reference value < 5 mg/L), without leucocytosis or neutrophilia; additional laboratory studies were normal, including serum electrolyte levels, liver and renal functions assessment and a negative urine pregnancy test.

No anomalies were identified in the abdominal x-ray.

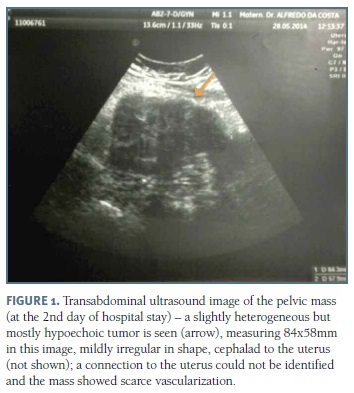

Transvaginal ultrasound detected an enlarged uterus, with a heterogeneous myometrial echotexture compatible with diffuse fibromyomatosis; the endometrium and adnexa were normal. With an abdominal probe a large pelvic mass was identified, that was previously missed during the vaginal approach. This mass, apparently originating from the uterine fundus, was 104 x 84 x 58 mm in size, with sonographic features of a subserosal and pedunculated uterine fibroleiomyoma (pedicle not seen), mildly irregular in shape and had absent vascularization on colour Doppler evaluation (Figure 1). These findings suggested a sub-torsion/torsion of a large uterine subserosal myoma. CA 125 blood levels were increased (=82,3 U/mL).

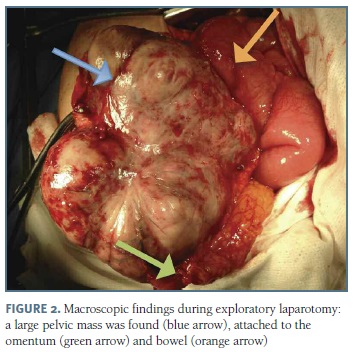

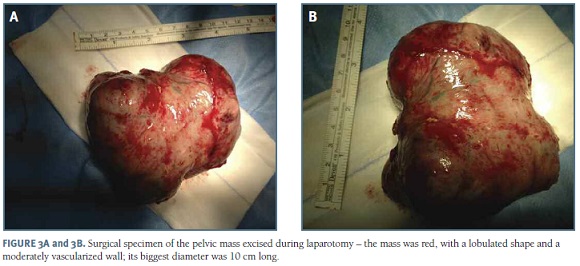

Taking into account the lack of clinical improvement with intravenous analgesia and sonographic impression of uterine myoma sub-torsion/torsion, an exploratory laparotomy was performed by a gynaecology surgical team that included a gynaecologic oncology surgeon. Intraoperative assessment found a 10 cm of diameter pelvic mass, attached to the omentum, sigmoid colon and right round ligament (Figure 2). Peritoneal fluid was collected for cytological analysis and adhesiolysis of the multiple dense adhesions that surrounded the tumour with the latter's consequent release and resection was performed (Figure 3). Extemporaneous examination of the resected tumour was consistent with a parasitic leyomioma. The omentum portion attached to the mass was also excised and sent to histological examination. Uterus was multinodular but otherwise macroscopically normal. A total intrafascial hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was decided, according to the patient's pre-surgical wishes and the uncertainty about the tumor's nature, despiste of the results of the extemporaneous examination. Surgery was uneventful.

Post-operative clinical evolution was favourable, with a remarkable improvement of pain symptoms. The patient was discharged 3 days after the surgery, clinically well. It was recommended that she kept taking oral iron supplementation daily and painkillers when necessary. At the post-surgical appointment, 8 weeks after, the patient was asymptomatic, with no morbidity to report.

Surgical specimen's gross examination showed a uterus measuring 8x5x7cm with multiple subserosal, intramural and submucosal myomas, their diameters ranging from 0,1 cm to 10,5 cm; the biggest one was multinodular, greyish in colour and separated from the hysterectomy specimen, corresponding to the large pelvic mass resected at the beginning of the procedure.

Microscopic analysis confirmed the presence of numerous benign uterine myomas, with areas of hyaline degeneration and the largest one with carneous degeneration; it also revealed: adenomyosis; endometrium with atrophic zones induced by external compression, in addition to secretory areas, where a polyp's base was identified; normal ovaries; fallopian tubes' congestion; omentum with vascular congestion, haemorrhage and a mild unspecific inflammatory reaction. Peritoneal fluid cytology was negative for malignancy.

Discussion

Uterine myomas' diagnosis is usually straightforward. However, parasitic myomas pose a diagnostic challenge because they're rare, vary in location and presentation, and are difficult to distinguish from other pelvic masses.

Our patient had a previous diagnosis of uterine leiomyomas, the main risk factor for parasitic myomas, but had never had any uterine surgery. Spontaneous parasitic myomas, like the one depicted in our case, are more rare than iatrogenic. A pedunculated subserosal myoma can outgrow its uterine vascular support, suffer torsion or its stalk may become longer and thinner4,5,9. All of these are possible mechanisms for myoma detachment from the uterus, leading to a wondering or migrating myoma4,5,9. During this process the myoma can adhere to surrounding structures for vascular supply3-5 and by doing so, they become parasites of the organ(s) involved. Parasitic myomas can be found attached to the omentum, broad ligament, pelvic peritoneum, cul-de-sac, retroperitoneal connective tissue, gastrointestinal tract, common iliac artery, inferior mesenteric artery, or, rarely, at the upper abdomen3,5,10-12. In our patient, the parasytic myoma seemed to be obtaining blood supply from the omentum.

Because parasitic myomas can be found in different anatomic sites, its clinical manifestations vary from: asymptomatic and incidentally identified in an imaging scan or surgery; to symptoms like pelvic pain (acute or chronic), mass sensation or, when bulky, complaints related to compression of neighbouring structures13,14.

Our patient presented with acute pain, probably due to the carneous degeneration that the parasitic myoma suffered, revealed in the histopathological exam. Degeneration occurs when the parasitic myoma outgrows its new vascular supply and the most common types are hyaline, cystic, mucoid and carneous15. Carneous (also called red) degeneration is a subtype of haemorrhagic infarction of leiomyomas, characterised on gross pathology, by a red (haemorrhagic) appearance16; it is one of the causes of acute abdomen in myomas17.

Parasitic myoma's imaging appearance, behaviour (benign, hormone-dependent) and histology are similar to typical uterine leiomyomas, but, being separa-ted from the uterus, they're often mistaken for other pelvic masses10,18. Additionally, when degeneration or necrosis occurs, atypical, even malignancy-like appearances can emerge, further complicating diagnosis5,11. Parasitic myoma's infarction can also explain its lack of vascularization on our patient's pre-surgical ultrasound17.

Differential diagnosis includes other pelvic or abdominal masses, such as: ovarian tumors, leiomyosarcomas, broad ligament cysts and lymphadenopathies3.

Patient's history and imaging techniques (pelvic ultrasound and magnetic resonance) are useful for an accurate diagnosis5. This condition must be suspected in patients with coexistent uterine myomas or a prior myomectomy/hysterectomy, especially if the approach was laparoscopic3. However, definite diagnosis is usually established after surgical excision15. In the case presented transvaginal ultrasound missed the large pelvic mass, only discovered with an abdominal probe and upper pelvis exploration. Even then, diagnostic uncertainty remained, between a pedunculated subserosal myoma and other pelvic masses (namely an adnexal tumor) and was only clarified during surgical exploration.

Surgery is indicated for symptomatic relief and to prevent the compromise of neighbouring vital structures; the approach depends on the intraoperative findings and the patient's future fertility wishes19.

In conclusion, parasitic myomas are rare, but part of the wide range of pelvic masses' differential diagnosis. They must be considered when its main risk factors are present: coexistent uterine fibromyomatosis and previous surgical treatment for myomas, especially if laparoscopic. Awareness to this condition is important because its incidence will likely increase in the laparoscopic area.

REFERENCES

1. Lete I, González J, Ugarte L, Barbadillo N, Lapuente O, Álvarez-Sala J. Parasitic leiomyomas: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:250-259. [ Links ]

2. Huang P-S, Chang W-C, Huang S-C. Iatrogenic parasitic myoma: A case report and review of the literature. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 5:392-396. [ Links ]

3. Fasih N, Prasad Shanbhogue AK, Macdonald DB, Fraser-Hill MA, Papadatos D, Kielar AZ, et al. Leiomyomas beyond the uterus: unusual locations, rare manifestations. Radiographics 2008; 28:1931-1948. [ Links ]

4. Kho KA and Nezhat CH. Parasitic myomas. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114(3):611-615. [ Links ]

5. Ravichandra G, Harishchandra B, Upadhyaya K, Acharya D, Madhurkar R. Parasitic uterine leiomyoma years after hysterectomy: a case report. International Journal of Medical and Applied Sciences 2013; 2(3):222-2225. [ Links ]

6. Cucinella G, Granese R, Calagna G, Somigliana E, Perino A. Parasitic myomas after laparoscopic surgery: an emerging complication in the use of morcellator? Description of four cases. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):e90-96. [ Links ]

7. Takeda A, Mori M, Sakai K, Mitsui T, Nakamura H. Parasitic peritoneal leiomyomatosis diagnosed 6 years after laparoscopic myomectomy with electric tissue morcellation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007; 14(6):770-775. [ Links ]

8. Thian YL, Tan KH, Kwek JW, Wang J, Chern B, Yam KL. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata and subcutaneous myoma - a rare complication of laparoscopic myomectomy. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34(2):235-238. [ Links ]

9. Park DS, Shim JY, Seong SJ, Jung YW. Torsion of parasitic myoma in the mesentery after myomectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013; 169(2):414-415. [ Links ]

10. Sreelatha S, Ashok Kumar, Vedavathy Nayak, Sahana Punneshetty, Nirmala Hanji. A rare case of primary parasitic leiomyoma. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2(3):422-424.

11. Nayk Ü, Nayk C, Uluğ P, Yılmaz I, Cetin Z, Yıldırım Y. A rare case of a giant cystic leiomyoma presenting as a retroperitoneal mass. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12(12):831-834.

12. Sinha R, Hegde A, Mahajan C. Parasitic myoma under the diaphragm. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(1):1. [ Links ]

13. Ángel-Cano G, Castro-Solís J, Arango-Martínez A. Parasitic leiomyomatosis in Medellín, Colombia: A case report and review of the literature. Revista Colombiana de Obstetricia y Ginecología. 2014;65(2):179-182. [ Links ]

14. Rabischong B, Beguinot M, Compan C, Bourdel N, Kaemmerlen AG, Pouly JL, Canis M, Mage G, Botchorishvili R. Long-term complication of laparoscopic uterine morcellation: iatrogenic parasitic myomas. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2013;42(6):577-584. [ Links ]

15. El-Agwany AS, Rady HA, Abdeldayem TM. A case of parasitic leiomyoma with serpentine omental blood vessels: An unusual variant of uterine leiomyoma. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 2014; 9(4): 338-340. [ Links ]

16. Murase E, Siegelman ES, Outwater EK, Perez-Jaffe LA, Tureck RW. Uterine leiomyomas: histopathologic features, MR imaging findings, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Radiographics. 1999;19(5):1179-1197. [ Links ]

17. Alharbi SR. Uterine leiomyoma with spontaneous intraleiomyoma hemorrhage, perforation, and hemoperitoneum in postmenopausal woman: Computed tomography diagnosis. Avicenna J Med. 2013; 3(3): 81-83. [ Links ]

18. Yeh H-S, Kaplan M, Deligdisch L. Parasitic and Pedunculated Leiomyomas: Ultrasonographic Features. J Ultrasound Med 1999;18:789-794. [ Links ]

19. Phupong V, Darojn D, Ultchaswadi P. Parasitic leiomyoma: a case report of an unusual tumor and literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(10):986-990. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Sofia Aguilar

E-mail: sofia6aguilar@gmail.com

Recebido em: 06/06/2017

Aceite para publicação: 26/08/2017