Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.12 no.1 Coimbra mar. 2018

CASE REPORT/CASO CLÍNICO

Carcinoma of the vulva in young women: a diagnosis to be kept in mind

Carcinoma da vulva na mulher jovem: um diagnóstico a ter em mente

Catarina Pardal*, Natacha Sousa**, Cátia Correia*, Carla Monteiro*, Paula Serrano***

Serviço de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia do Hospital de Braga

*Assistente hospitalar no Hospital de Braga

**Interna de formação específica de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia do Hospital de Braga

***Assistente Hospitalar Graduada, Sub-especialista e Mestre em Ginecologia Oncológica

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Although the incidence of preinvasive vulvar lesions seems to be rising in the younger population, invasive squamous cell carcinoma remains exceedingly rare. As a result, diagnostic biopsy is often delayed and ablative therapy is frequently instituted without an adequate histologic diagnosis.

We present an invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva in a 28-year-old nulliparous woman who presented with a painless vulvar ulcer for the past 6 months. Biopsy revealed an invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Conservative surgery (tumorectomy with safety margins and sentinel lymph node biopsy) was performed with good patient recovery and return to normal working life before 30 days.

Keywords: Vulvar cancer; Premenopausal; Human papillomavirus infection.

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the vulva is an uncommon disease accounting for 4% of all gynaecological cancers1. In Portugal, the incidence rate in 2010 was 3.2/100000 women2. The disease typically develops in older women and is rarely seen in patients younger than 35 years of age1. Recently, an increase in the incidence of vulvar SCC in young women has been observed1,3,4, and besides the known association with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, immune suppression conditions and tobacco use have also been implicated as predisposing factors in the development of SCC in this age group3-6.

Attempting an early diagnosis is the key, since the 5-year survival in early stages (FIGO I-II) is high (>80%), falling to less than 50% if the inguinal nodes are involved and 10-15% if the iliac or other pelvic nodes are positive4. Additionally, in the young sub-group of patients, the often mutilating local treatment required in advanced stages of the disease has more potential mental trauma associated, and this psichological aspect should not be minored.

Case report

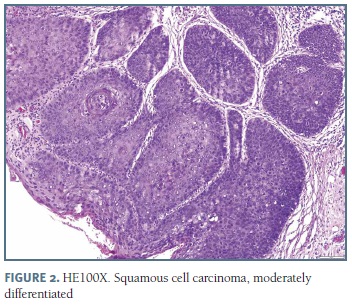

A nulliparous 28-year-old caucasian female presented to the gynecologic clinic harboring a positive cervical co-test: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) plus high-risk HPV positive (excluding HPV-16 and HPV-18). She mentioned a painless vulvar lesion for the past six months. Her past and family history were irrelevant, except for tobacco use (5 cigarettes/ /day). She refered 21 as the age of sexual initiation and two sexual partners since then. The contraceptive method was the combined oral contraceptive pill. The physical examination was relevant for a 8mm vulvar ulcer, localized lateral to the posterior fourchette (Figure 1); the cervix was macroscopically normal and the colposcopy was adequate for evaluation, with a squamo-columnar junction not visible, a transformation zone type 3 and no abnormal findings. The vagina had normal colposcopic findings, and vulvoscopy revealed no additional lesions. Punch biopsy of the vulvar ulcer revealed a specimen (1.2 cm) with HSIL and SCC with stromal invasion > 1 mm (cFIGO >=IB) (Figure 2). In the diagnostic assessment, essential and aquired immunossupressive disorders were excluded and the patient underwent surgical staging with double ipsilateral sentinel lymph node technic. Lymphocintigraphy was performed the day prior to surgery and showed two right inguinal nodes (‘hot' nodes). The intra-operative peri-tumoral injection of metilene-blue marked the same 2 nodes (‘blue' nodes) with frozen biopsy negative for carcinoma. Conservative vulvar surgery with radical tumorectomy with apparent safety margins was performed plus large loop excision of transformation zone. The patient had an uneventfull postoperative and was discharged 3 days later. The definitive histologic assessment revealed a vulvar SCC (pT1bG2N0 (SN) - FIGO IB) with 1 cm free margin, and in the cervical specimen only LSIL was present.

The patient is in her first year of follow-up (Colposcopy Unit and Gynaecologic Oncology Unit), with satisfatory surgical esthetical results, no complaints of dispareunia or vulvodynia and with no disease recurrence to date.

Discussion

Vulvar cancer is rare, especially in very young patients with most of the published data presented as case reports. By age group, the incidence trend of vulvar SCC has remained relatively stable over the last three decades, although the incidence in women aged 40-49 years has risen two-fold4. This increase has been reflected in many reports from several countries1,3,4 and has been ascribed to the effect of increasing HPV infection7, particularly types 16, 18 and 33. Despite the known HPV infection pathogenesis in genital carcinoma, other predisposing factors such as depressed immunity have been implicated in the progression of VIN/HSIL to invasive disease at an earlier age. Factors affecting a patient's immunity include genetic factors, oncogenic virus exposure, medical conditions (ex. diabetes, lupus), immunossupressive or cytotoxic chemotherapy, as well as exposure to carcinogenic substances. Smoking has been implicated in the development of the invasive genital cancers, and it appears to lead to humoral immune suppression and such immune response appears to be responsible for reactivation of viroses remaining latent in tissues6. This precipitates a local immunodeficiency, allowing the patient to be susceptible to other co-factors which predispose to the development of dysplasia or intraepithelial neoplasia and subsequent invasive cancer.

Despite the presence of several risk factors that increase the odds of developing vulvar cancer, most women do not develop it, and some women who don't have any apparent risk factors develop vulvar cancer. In our patient, both high risk HPV infection and smoking status were pesent. However, young patients with these risk factors and a competente immune system, rarely present with invasive neoplasia. Other factors not fully understood might be implied in the carcinogenesis of these neoplasias. An interesting fact is that the cervical lesion detected in the transformation zone specimen, which is the most susceptible area to HPV infection and associated intra-epithelial neoplasia, was of lesser severity than the vulvar lesion. And also, that the disease was focal, rather than with the typical multifocal pattern of usual VIN. However, vulvoscopy has low sensitivity for VIN, and other lesions might have been present without colposcopic detection, meaning a long period of close follow-up is of most importance in these patients. A conservative approach, such as the one described in the case report, is the treatment of choice in this subpopulation, but obtaining a disease-free margin of at least 1 cm is the most important prognostic factor for recurrent disease. Particularly in this young population, the avoidance of radical surgery which is associated with major distortion of normal vulvar anatomy, is fulcral for the woman's self-esteem.

Young women with vulvar SCC do not appear to have more advanced disease when first diagnosed or to have a different course of the disease compared with their elderly counterparts. However, in this subgroup of patients the development of other genital carcinomas later in life is more frequent (new primary lesions rather than recurrence of the original vulvar carcinoma) and an increased awareness of cervical, vaginal and vulvar symptoms are mandatory.

The optimal follow-up schedule for vulvar cancer is undetermined, but the European Society of Gynaecologic Oncology recommend clinical examination of vulva and groins every three-four months in the first two years, biannually in the third and fourth year, and anual long-term follow-up afterward8. Currently, our patient is in surveillance in the Colposcopic Unit and Gynaecologic Unit every 3 months period, with no recurrent disease. Because of the high risk of recurrence and other lower genital dysplasia/neoplasia lesions, the patient was encouraged to perform self-examination and report any suspicious lesions encoutered at any time.

Although rare, vulvar SCC in young women is a possibility with potentially life-threatening implications and is certainly a diagnosis to be kept in mind.

REFERENCES

1. Neville F. Hacker, Patricia J. Eifel, Jacobus van der Velden. FIGO cancer report 2015. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 131 (2015) S76-S83.

2. RORENO. Registo Oncológico Nacional 2010. Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto Francisco Gentil - EPE, ed. Porto, 2016. [ Links ]

3. Al-Ghamdi A., Freedman D., Miller D., et al. Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Young Women: A Clinicopathologic Study of 21 Cases. Gynecologic Oncology 2002, 84, 94-101. [ Links ]

4. RCOG Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Vulval Carcinomas. https://www.rcog.org.uk [ Links ]

5. Linn Woelber, Fabian Trillsch, Lili Kock et al. Management of patients with vulvar cancer: a perspective review according to tumour stage. TherAdv Med Oncol. 2013 May; 5(3): 183-192.

6. Carter J, Carlson J, Fowler J, et al. Invasive vulvar tumors in young women-a disease of the immunossuppressed?. Gynecol Oncol 1993;51:307-10. [ Links ]

7. Cancer Research UK. Vulval cancer incidence statistics http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/vulva/incidence/ [ Links ]

8. ESGO. Vulvar Cancer Guidelines. https://www.esgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ESGO-Vulvar-cancer-Complete-report.pdf [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Catarina Pardal

Hospital de Braga

Braga, Portugal

E-mail: catarinapardal_84@hotmail.com

Recebido em: 23/98/2017

Aceite para publicação: 19/10/2017