Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.14 no.3 Coimbra set. 2020

ORIGINAL STUDY/ ESTUDO ORIGINAL

Radiation-induced endometrial cancer after cervical carcinoma

Cancro do endométrio após radioterapia por carcinoma do colo do útero

Maria Carlota Cavazza1, Alexandra Rico Sofia2, Catarina Travancinha3, Ana Francisca Jorge4

Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil E.P.E

1 Interna de formação especializada de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia

2 Assistente hospitalar em Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, IPOLFG

3 Assistente hospitalar em Radioterapia, IPOLFG

4 Assistente graduada sénior em Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, IPOLFG

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Overview and Aims: Cases of radiation-induced endometrial cancer after cervical carcinoma are characteristically different than sporadic cases of endometrial cancer as they tend to be more aggressive, diagnosed in a more advanced stage, and with a poorer outcome. Therefore, it is important to maintain surveillance, be aware of the warning signs and know how to approach these secondary cancers in order to assure the best outcome for these patients. The goal of our study is to describe a case series of patients with radiation-induced endometrial cancer after cervical carcinoma followed at our institution.

Study design: Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Population: Patients with a diagnosis of endometrial cancer who had previously received definitive radiation treatment for cervical cancer. Four patients met our inclusion criteria.

Methods: Analyzed parameters included patient demographics, age upon diagnosis, type of radiation therapy, histological grade and subtype of the primary and the secondary cancers.

Results: The mean age at diagnosis of the primary cervical cancer was 64 years. All of the patients had received definitive radiation therapy and chemotherapy. The mean latency period between the initial diagnosis of cervical cancer and the development of the endometrial carcinoma was 5.3 years. Two patients had stage I disease, one had stage II and one had stage III. Regarding the histological type, there was one case of endometrioid carcinoma, one of carcinosarcoma and two of serous carcinoma. All of the patients underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and three received chemotherapy as adjuvant therapy. Three patients maintain their follow-up in our institution without any evidence of disease.

Conclusion: Regular surveillance based on anamnesis and physical examination is of the most importance in women that underwent radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma. Imaging tests can aid in this particular subset of patients as cervical stenosis might hide an underlying condition. In our sample, only one patient complained of abnormal uterine bleeding and three patients had an aggressive histological type of endometrial cancer diagnosed. The latency period between the primary and secondary cancers was shorter than expected and might be related to small size of the sample.

Keywords: Radiation-induced endometrial cancer; Cervical cancer.

Introdução

Radiotherapy contributes to 5% of the total treatment related second cancers as the carcinogenic potential of ionizing radiation is a well-known effect1. According to the modified Cahan' s criteria, a radiation-induced malignancy must rise in a previously irradiated field and after a sufficient latent period of at least 4 years. Additionally, both tumors must be biopsied and proven to have a different histology and, finally, the tissue in which the radiation-induced tumor rises must be normal prior to the irradiation.

In opposition to sporadic cases, radiation-induced endometrial cancers tend to be diagnosed later and of a higher risk (type 2). Also, abnormal uterine bleeding is not a typical presenting sign as cervical stenosis is usually present. Some authors suggest that the incidence of these secondary cancers is growing 2. Therefore, it is important to analyze their natural history and understand the mechanism behind their occurrence. The goal of this study is to describe a series of four cases of endometrial cancer occurring after radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma.

Métodos

The databases of the Gynecology Department of the Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa, Francisco Gentil E.P.E were searched for patients who had history of definitive radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma and subsequently developed an endometrial neoplasia. Four patients met our criteria. The authors then performed a retrospective analysis to obtain the details of the prior cervical cancer - age at diagnosis, histological type, stage and radiotherapy regimen used - latency period to the development of endometrial cancer and the details of the secondary neoplasia - histological type, stage, treatment and follow-up.

Resultados

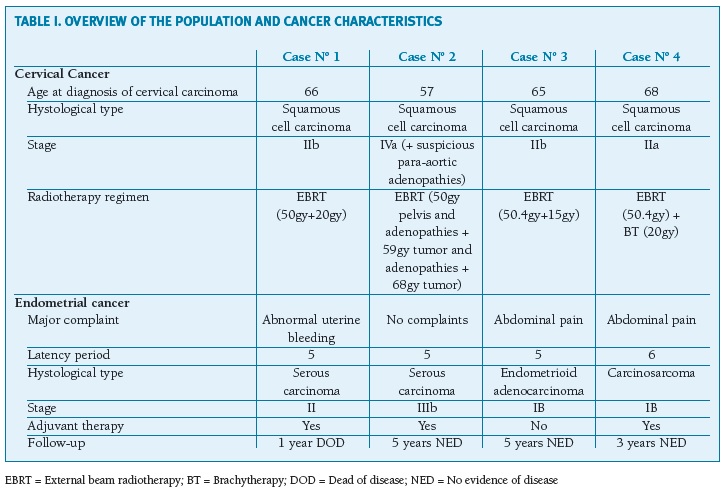

The main clinical characteristics of the four patients are outlined on Table I. The mean age at diagnosis of the primary cervical cancer was 64 years (range 57-68). One of the patients (case number 4) had a thyroid malignancy diagnosed one year after the diagnosis of the cervical cancer for which she underwent thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy. All of the patients had received definitive radiation therapy: one received both external beam and brachytherapy and the other three received external beam irradiation only as they were found not suitable for brachytherapy. In these cases, boost doses of external beam radiotherapy were given. All patients received concurrent chemotherapy.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

The mean age of the patients upon the diagnosis of endometrial cancer was 69.3 years (range 62-74). The mean latency period between the initial diagnosis of cervical cancer and the development of the endometrial carcinoma was 5.3 years (range 5-6). Two patients presented with abdominal pain and one with abnormal uterine bleeding. One patient did not have any complaints or symptoms. In this case, the secondary cancer was suspected after imaging findings showed three polypoid endometrial lesions and a fluid-filled endometrial cavity. Due to the radiation-induced cervical stenosis, endometrial sampling prior to the surgery was not achieved in three patients. All four patients underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy and three of them received adjuvant therapy with chemotherapy. Two patients had stage I disease, one had stage II and one had stage III. Regarding the histological type, there was one case of endometrioid carcinoma, one of carcinosarcoma and two of serous carcinoma. Three patients maintain their follow-up in our institution without any signs of disease and one patient (case number 1) passed away one year after the diagnosis of the endometrial carcinoma. This patient had a concurrent vaginal node with an histological diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and was not capable of endure the chemotherapy regimen.

Discussão

The authors present four cases of endometrial cancer after radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma. There are not many studies on this subject and, most of those available, are either single case reports, series comparing to sporadic endometrial cancer or were published or refer to patients treated during the second half of the twentieth century, when treatment protocols for cervical carcinoma were different from those performed nowadays. To our knowledge, there are not any case series describing radiation-induced endometrial cancers after cervical carcinoma referring to patients treated in the recent decades. These are surely the strongest points of our work as, in all four cases, the modified Cahan' s criteria are met and all patients were treated for their cervical carcinoma with current radiotherapy protocols. Reported series have shown that the incidence of endometrial carcinoma after radiation therapy is approximately 0.5-0.8% 3. Some authors suggest that this rate is growing due to a longer survival of the patients treated for the cervical carcinoma as they tend to be younger and have an early staged tumor at diagnosis. Improvement in radiotherapy techniques during recent years has also be pointed out to be a reason for the longer survival times4.

Nevertheless, the dose being given should lead to an irreversible endometrial ablation and, therefore, in theory, a secondary endometrial neoplasia should not occur. This has already been demonstrated not to be true since rates of active endometrial tissue in patients previously submitted to uterine irradiation can be as high as 62.5%4. Furthermore, Hullu et al showed that some women that had been treated with radiation for a cervical carcinoma have regular bleeding when taking hormonal therapy. The mechanism leading to this residual endometrial function may be related to the menstrual cycle phase in which the treatment is started, as G0 cells tend to survive to radiation as they are in a quiescent state5. The process leading to radiation- induced malignancies is not fully understood. With high-dose radiation exposure, as is the case of our patients, the production of inflammatory cytokines from radiated cells is transferred to normal cells leading to the release of reactive oxygen and causing DNA damage6. A long latency period between the primary cancer and the development of the endometrial cancer supports the hypothesis that the last one is radiation induced as time is needed for the accumulation of sufficient mutations leading to the secondary cancer. Pothuri et al, in their analysis of 23 cases of endometrial cancer following radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma, described a mean latency period of 14 years (6-27)3. This longer period was not observed in our cases and may be related to our small-sized sample.

In our institution, the radiotherapy treatment protocol used for cervical cancer follows the GEC- ESTRO guidelines. Prophylactic doses are given to the lymphatic nodes while the uterus receives, normally, a dose of 45-50gy. These doses are augmented if there is evidence or suspicion of node disease. After EBRT, the patient receives intracavitary and intrauterine brachytherapy. In patients that are not eligible for brachytherapy, an additional dose of EBRT is given to the tumor and its margins, summing a total dose of 70gy. In our sample, the technique of EBRT used was intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) for cases 1 and 2 and three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for cases 3 and 4, as it was the technique available when these patients were treated. In IMRT, a maximized dose is delivered to the planned treatment volume while minimizing radiation outside of it. Nevertheless, comparing with older techniques, IMRT results in a larger volume of normal tissue receiving lower doses of radiation and in a prolonged time of exposure for each treatment. The impact of these specific characteristics of IMRT remains unknown. However, preliminary results of a study conducted at the Stanford Cancer Institute in the United States show that the risk of secondary cancers was similar between three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy and IMRT 7.

On the other hand, brachytherapy delivers substantially less radiation and has a greater dose fall-off than EBRT. For these reasons, secondary cancers tend to be less associated with brachytherapy treatment regimens. In their study of patients previously treated with radiotherapy for corporal uterine cancer, Lönn et al, described an overall risk of second solid cancers elevated by 13% following external beam therapy and 28% after combination of EBRT and brachytherapy whereas it was only slightly augmented following brachytherapy alone8. In our sample, the only patient who received brachytherapy ended up developing a carcinosarcoma, a specifically aggressive type of endometrial cancer (case 4). We did not find any studies regarding an eventual relationship between combination therapy and the development of a more aggressive secondary cancer. Nevertheless, taking into account that combination therapy appears to influence the risk of a secondary cancer, we wonder if it could also have an impact on its histological subtype.

On one of the cases, abnormal uterine bleeding, a common and early occurrence in endometrial cancer, was the clinical symptom leading to the diagnosis of the secondary cancer. In the other three cases, abdominal pain was the main complaint and, in all, an hematometra was found. One patient did not have any signs or symptoms of disease. A study conducted by the radiology department of our institution, in which the imagiological characteristics of the uterus were studied, found that an hematometra was present in 85% and a cervical stenosis in 77% of patients with an endometrial cancer after radiation treatment for a cervical carcinoma 9. This is in accordance with other studies as the stenosis and occlusion of the cervical canal caused by radiotherapy create an obstacle for the discharge of the blood thus leading to uterine distention and pain10. In fact, only in the case in which the patient complained of abnormal uterine bleeding (case 1), a pre-operative endometrial biopsy confirming the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma was achieved. In the other three cases, even though attempts of retrieving endometrial tissue through either hysteroscopy or traditional endometrial biopsy pipette were made, the diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma was only established during surgery or postoperatively. As abnormal vaginal bleeding is unusually present, radiation-associated endometrial cancers tend to be in a more advanced stage as they, probably, have a later diagnosis. However, in two of our cases, diagnosis was established at an early stage (IB). This is surely a sign of the importance of anamnesis and physical examination on the long term surveillance of patients who had undergone radiation therapy. As Kumar et al described in their study, although a specific screening program can not be recommended for women at risk of a secondary cancer, a high degree of suspicion must be present amongst the medical professionals, specially when evaluating patients with nonspecific symptoms11.

It is well established that radiation-associated endometrial cancers have a worse prognosis than sporadic cases as they tend to have a higher grade of differentiation and to be of a higher risk histological subtype12. The authors describe two cases of serous carcinoma and one of carcinosarcoma. These patients underwent adjuvant therapy. On the first case, the poor outcome of the patient might also have been influenced by the finding of squamous cell carcinoma on the vaginal node and the patient' s intolerance to the chemotherapy regimen.

Radiation-induced endometrial cancers tend to be more aggressive, diagnosed in a more advanced stage and have a poorer outcome than sporadic endometrial cancers. The technique of EBRT does not appear to influence the risk of development of secondary cancers. Of the four cases presented, only one had abnormal vaginal bleeding enhancing the importance of a high degree of suspicion in the follow-up of these patients. Three patients had a high risk histological subtype, with one of these patients passing away one year after the diagnosis possibly due to the concomitant presence of a cervical cancer recurrence in the vagina.

REFERENCES

1. Dracham C, Shankar A, Madan R. Radiation induced secondary malignancies: a review article. Radiat Oncol J. 2018;36(2):85-94 [ Links ]

2. Ota T, Takeshima N, Tabata T, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix with radiation therapy alone: long-term survival, late complications and incidence of second cancers. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(B):1058-1062. [ Links ]

3. Pothuri B, Ramondetta L, Martino M, et al. Development of endometrial cancer after radiation treatment for cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 Pt1):941-945. [ Links ]

4. Barnhill D, Heller P, Dames J, et al. Persistence of endometrial activity after radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:805-808. [ Links ]

5. Hullu JA, Pras E, Hollema H, et al. Presentations of endometrial activity after curative radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Maturitas. 2005;51:172-176. [ Links ]

6. Chaowawanit W, Tangjitgamo S. Uterine Carcinosarcoma after pelvic radiotherapy. Clinic in Oncology. 2016;Vol.1:Article 1049.

7. Xiang MH, Chang DT, Pollow EL. Risk of subsequent cancer diagnosis in patients treated with 3D conformal, intensity modulated, or proton beam radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37S:ASCO#1503.

8. Lönn S, Glibert E, Ron E, et al. Comparison of second cancer risks from brachytherapy and external beam therapy after corpus cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(2):464-474. [ Links ]

9. Lopes J, Horta M, Cunha TM. Endometrial cancer after radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma: a radiological approach. 2018;105:283-288.

10. Vernooij CB, Kruitwagen RF, Rodrigues P, et al. Hematometra after radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:325-327. [ Links ]

11. Kumar S, Shah JP, Bryant CS, et al. Radiation-associated Endometrial Cancer. Obst Gynecol. 2009;113:319-325. [ Links ]

12. Pothuri B, Ramondetta L, Eifel PJ, et al. Radiation-associated endometrial cancers are prognostically unfavorable tumors: A clinicopathologic comparison with 527 sporadic endometrial cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(3):948-951. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Maria Carlota Cavazza

E-Mail: mcarlota.cavazza@gmail.com

Recebido em: 05/02/2020. Aceite para publicação: 11/07/2020.